J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(5):19–28.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(5):19–28.

by Valeria González-Molina, MD; Alicia Martí-Pineda, BS; and Noelani González, MD

Dr. González-Molina is with St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital Transitional Year Program in Ponce, Puerto Rico. Dr. Martí-Pineda is with the Universidad Central del Caribe School of Medicine in Bayamon, Puerto Rico. Dr. González is with Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, New York

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Objective. We conducted a review of topical agents currently used in melasma, discussing their mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and tolerability, with an update on newer treatments.

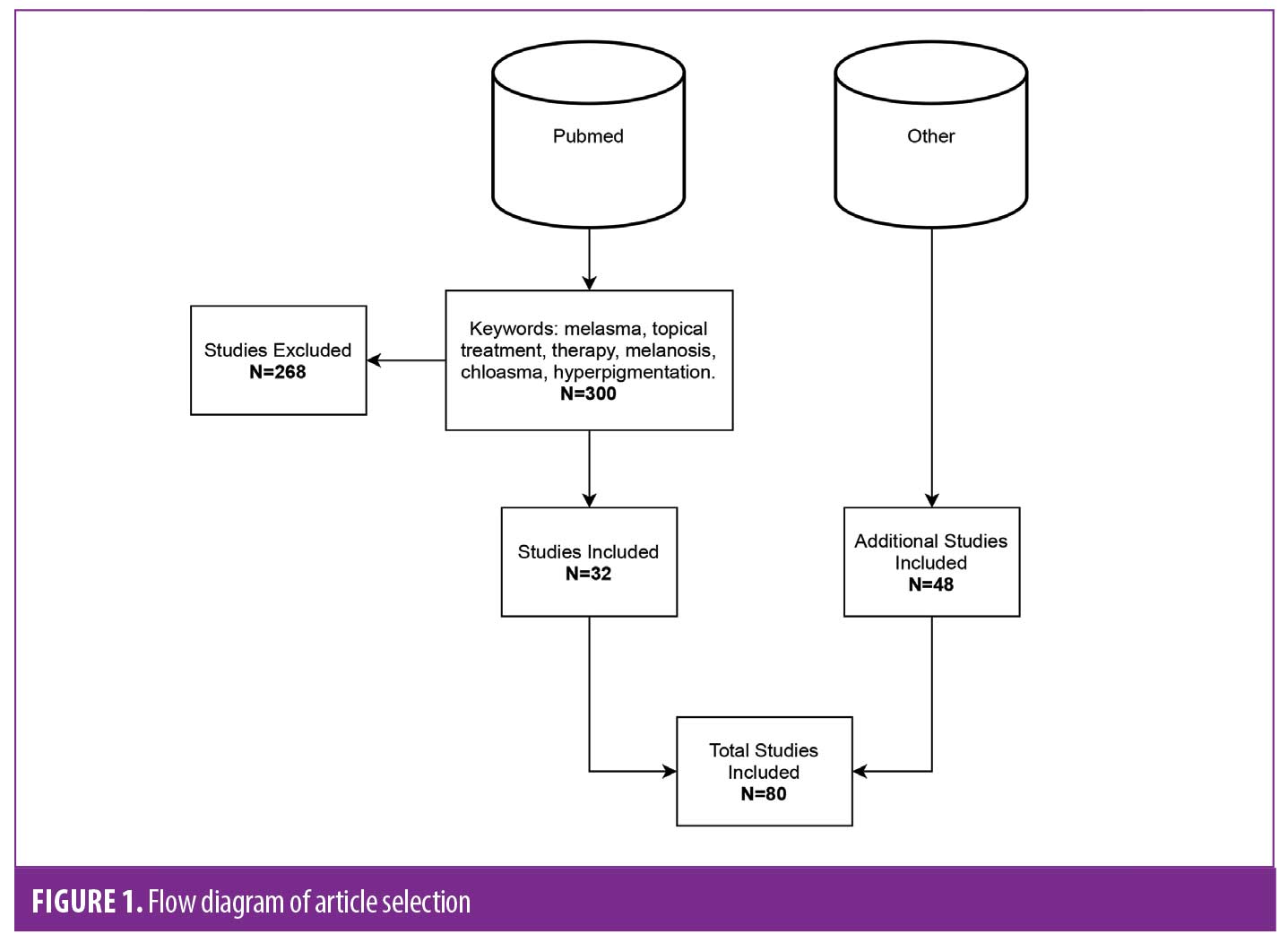

Methods. A systematic review from PubMed database was performed, using PRISMA guidelines. The search was limited to English and Spanish studies that were double or single blinded, prospective, controlled or randomized clinical trials, reviews of literature, and meta-analysis studies.

Results. 348 studies were analyzed; 80 papers met inclusion criteria. Triple combination (TC) therapy and hydroquinone (HQ) are still the most well-studied agents with strong evidence-based recommendation. TC therapy remains the gold standard of care based on efficacy and patient tolerability. Evidence has shown ascorbic acid, azelaic acid, glycolic acid, kojic acid, salicylic acid, and niacinamide to be effective as adjuvant therapies with minimal side effects. Tranexamic acid (TA) and cysteamine have become recent agents of interest due to their good tolerability, however more trials and studies are warranted. Less evidence exists for other topical agents, such as linoleic acid, mulberry extract oil, rucinol, 2% undecylenoyl phenylalanine, and epidermal growth factors agents.

Limitations. Some studies discussed represented a low sample size, and there is an overall lack of recent studies with larger populations and long-term follow up.

Conclusion. TC therapy continues to be the gold standard of care. Topical cysteamine and TA are newer options that can be incorporated as adjuvant and maintenance treatments into a patient’s regimen. Cysteamine and topical TA have no known severe adverse effects. Evidence comparing other topical adjuvant treatments to HQ, maintains HQ as the gold standard of care.

Keywords: melasma, topicals, therapy, melanosis, chloasma, peels, depigmentation, skin-lightening agents, depigmented agents

Melasma is a challenging condition to treat due to its unpredictable course and common relapses. It is typically characterized by dark-brown symmetric patches with irregular borders. These occur most commonly on the face in a centrofacial and malar pattern.1 Other less common presentations are lesions on the scalp, forearms, and back.2 It is most prevalent among Fitzpatrick Skin Type III to VI, Hispanics, African Americans, Asians, or Middle Eastern females, and tends to present in patients between the ages of 20 and 40.3 Though less common, males account for 10 percent of cases and typically present with a malar pattern distribution.2 The exact pathogenesis of melasma is unknown. Sun exposure, oral contraceptives, pregnancy, medications (e.g., photosensitive drugs), genetic predisposition (mainly first-degree relative), certain cosmetics, and autoimmune disorders have all been found to aggravate and contribute to the clinical signs of melasma.4,5 Histologically, it is classified as involving the epidermis (this type being more responsive to treatment), dermis, or both, and can be clinically diagnosed with a Wood’s lamp.1 Furthermore, gaining insight into the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and side effects of the topical agent chosen by the provider is essential for obtaining desirable results and avoiding adverse effects and relapses.

Due to its complexity and location, melasma causes a deleterious impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Studies have shown that patients with melasma reported low self-esteem, were more self-conscious, avoided outdoor activities, and experienced frustration with costly and ineffective treatments.6,7

Many topical agents are available for the treatment of melasma. Hydroquinone is considered the gold standard due to its superior efficacy.8 Other topical agents include niacinamide, retinoids, steroids, tranexamic acid, azelaic acid, glycolic acid, salicylic acid, ascorbic acid and kojic acid. Triple combination therapy comprised of hydroquinone, a retinoid, and a steroid has demonstrated strong clinical efficacy and is considered as first-line treatment for melasma by many.9 In addition, sunscreen is of paramount importance for any treatment regimen to be successful.10

Recent studies for the treatment of melasma have been conducted for novel depigmenting agents, as well as new formulations in combination with well-studied agents for the purpose of reducing adverse effects of some of these topical agents.11 Cysteamine, known for its treatment of cystinosis, has been shown to have skin-lightening properties, becoming a beneficial agent of interest. Studies have not only reported a statistically significant reduction in MASI score with this newer agent, but also good tolerability in patient’s skin with application of cysteamine cream.12, 13

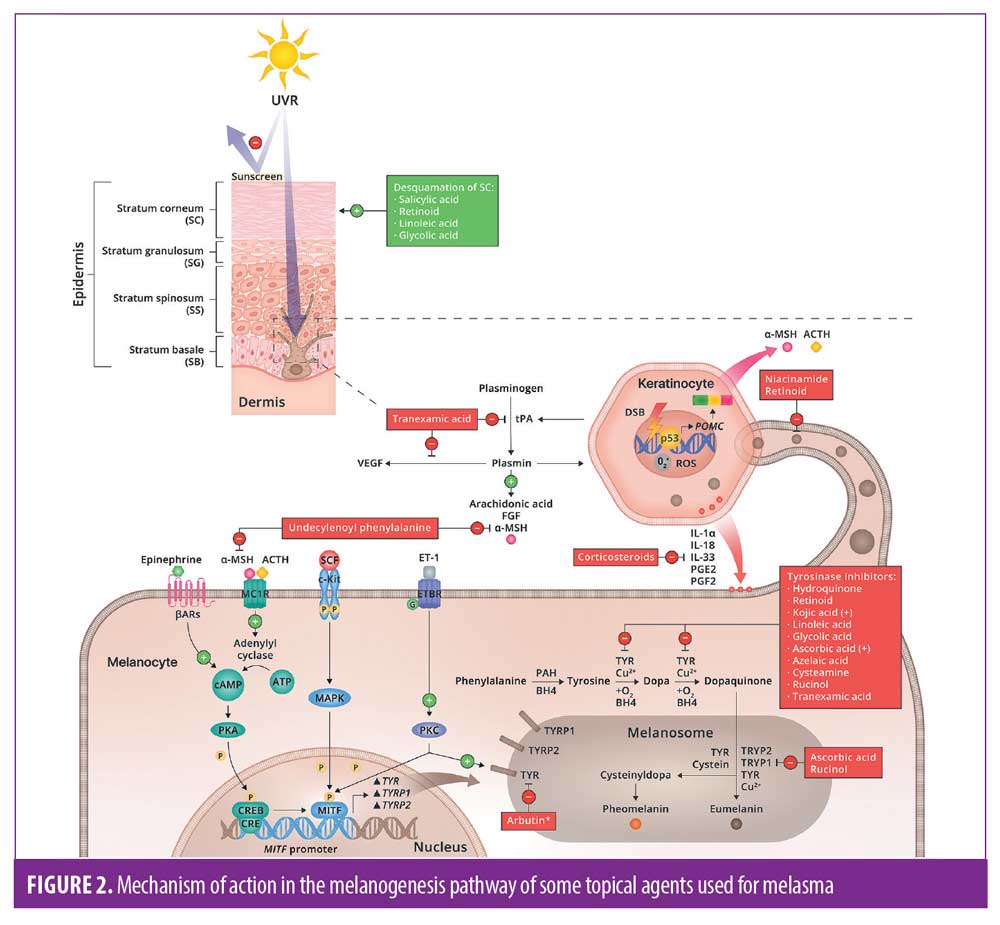

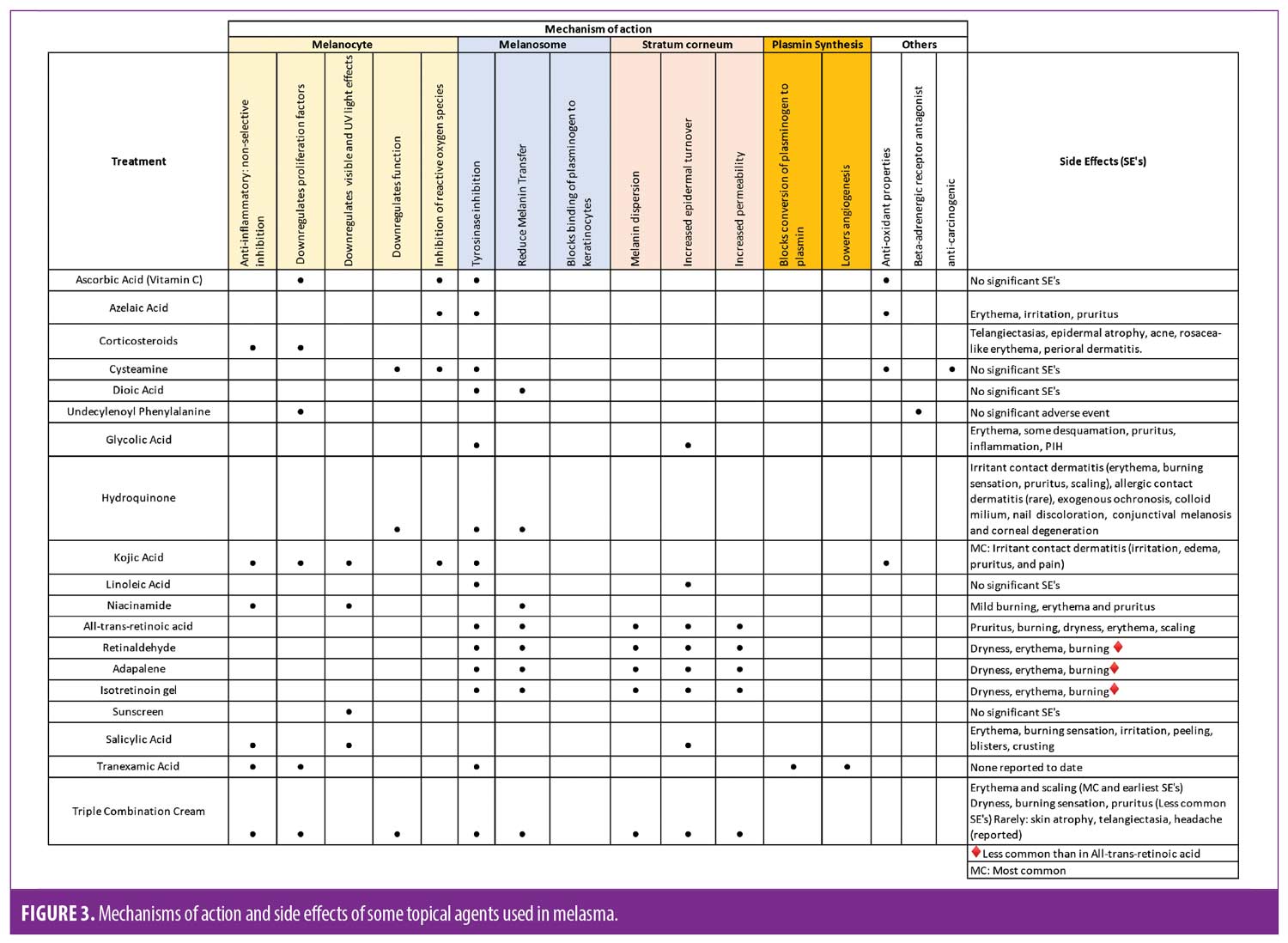

It’s necessary to have a comprehensive understanding of the melanogenesis pathway when treating this condition; and can benefit the reader in the selection of topical agents as well as adjuvant treatments. The mechanism of action of the various topical agents that will be discussed range from providing broad spectrum ultraviolet (UV) and visible light (VL) protection, to inhibiting tyrosinase activity, reducing melanocytes activity, and/or disrupting the transfer of melanosomes amongst others.3 There are also agents which diminish angiogenesis. This is currently being studied as a contributing factor for melasma.14 These mechanisms of action will be discussed further below.

The efficacy and safety of complementary procedures such as chemical peels, dermabrasion, microneedling, and lasers has been addressed in many studies and demonstrated good results. These may be used once topical therapy has been initiated, during the maintenance phase, or as an adjuvant for individuals that develop sensitivity with monotherapy or have a refractory response with the proposed topical regimen.1,9

Methods

Process of selection. Data was collected through an extensive literature search from the Pubmed database. Keywords used were ‘melasma’, ‘topical treatment’, ‘therapy’, ‘hyperpigmentation’, ‘melanosis’ and ‘chloasma’. Three hundred and forty-eight articles were found and analyzed (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria was based on English or Spanish studies that were double or single blinded, prospective, controlled or randomized clinical trials, review of literature or meta-analysis studies. Exclusion criteria were as follows: treatments for other diseases, papers written in languages other than English and Spanish, or those focusing on energy-based devices, microneedling or chemical peels. Additional studies were obtained from references in studies included.

Topical treatment agents

Melanin pathway. Figure 2 shows the mechanism of action of the topical agents that will be discussed and their respective targets in the melanin pathway. Additionally, it depicts the mechanism in which UV light promotes angiogenesis, which may manifest as vascular lesions in melasma.

Hydroquinone. MOA. Hydroquinone (HQ), a hydroxyphenolic chemical, has been known for many years to be the gold standard drug for the treatment of melasma due to its ability to inhibit the conversion of DOPA to melanin, by binding to copper resulting in tyrosinase inhibition.8 In addition, HQ has been shown to play a role in the degradation of melanosomes and melanocytes.15

Efficacy/study findings. In the mid-1900s, scientists evaluated the efficacy of HQ 1.5%-5% in patients with melasma and noticed a considerable improvement in pigmentation.16 Subsequent studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of HQ versus other depigmenting agents used for melasma. An open-comparative study of 96 patients comparing HQ with dioic acid (a depigmenting agent) found a statistically significant decrease in Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) score after 12 weeks of treatment with HQ 2% (twice daily) alone.17 A 25-patient, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study compared the efficacy of HQ 4% and a skin whitening complex (SWC) (contained extract of uva-ursi, grapefruit and rice, and biofermented Aspergillus) 5% cream versus the placebo throughout a 12-week period. According to two independent investigator evaluations and a patient questionnaire by Week 12, a 76.9-percent improvement rate was reported in those treated with HQ and placebo versus a 66.7-percent improvement with SWC and placebo. No statistical difference was found between the two groups, but the efficacy of HQ was compatible with findings of other studies.18 Moreover, in a double-blind RCT, 54 individuals with melasma were treated with brewed parsley in one side of the face and HQ 4% cream (once daily) on the other side of the face and were evaluated after eight weeks of treatment. A statistically significant decrease in MASI scored compared to baseline occurred on the side treated with 4% HQ cream.19 In a small, most recent double-blinded RCT study of liposomal HQ alone or HQ 4% given to 20 patients once daily for 12 weeks, a statistically significantly reduction in MASI score was found for both agents without any statistical difference between them.20 This study showed that liposomal HQ not only has a significant therapeutic effect for melasma, but it’s vehicle form can be beneficial to patients given its advantages reducing HQ’s common side effects. Positive, yet variable, results with the use of HQ for melasma are evident for 60%-90% of treated patients after 5 to 7 weeks of treatment.

Tolerability and side effects. The most common reported adverse effect is an irritant contact dermatitis characterized as erythema, burning sensation, pruritus and scaling. This has shown to be a common short-term adverse reaction that can be seen in up to 70% of patients mostly with doses of HQ 4% or higher, although it can occur in a variety of HQ concentrations.16,18 Other uncommon side effects are nail discoloration, colloid milium, paradoxical post-hyperpigmentation, guttate hypomelanosis, conjunctival melanosis, and corneal degeneration. Cases of HQ inducing hypopigmentation have been reported mainly in darker skin complexions.16 The main concern with long-term use of HQ is exogenous ochronosis, in some cases it has been reported after a short three-month period use of HQ 2% in Skin Types I to III. It has also been reported among Skin Types IV to V with prolonged use of high concentrations of HQ (>5%) for six months. However, this side effect can be avoided by close monitoring and limiting the period of use of hydroquinone. 16 In addition, there have been cases of allergic contact dermatitis reported, but these are rare, irritant contact dermatitis is more common.18

Although HQ has been used safely in humans for the treatment of dyschromia for over 50 years, concerns of topical use of hydroquinone persisted by the FDA. In 2006, the FDA proposed to ban over the counter (OTC) hydroquinone of 1–2% mainly because of concerns of high absorption, risk of exogenous ochronosis in human studies, and carcinogenicity findings in animal studies.22,23 It was officially taken off the market in 2020 with the passing of the CARES act. Currently, hydroquinone products can only be distributed if the FDA approves them through a new drug application process or in compounds of patient-specific prescriptions. This was mainly due to reported cases of exogenous ochronosis with low doses of HQ (1-2%), accompanied by the easy accessibility of unregulated OTC HQ.23, 24 Moreover, in-vitro studies in rodents have shown HQ to be a carcinogen. However, these studies were done using high doses of HQ, administered orally or parenterally, and for an extended period of time.23–25 Regarding carcinogenicity findings, there is no adequate data supporting that hydroquinone is carcinogenic to humans. To date, there are no cases linking the topical use of hydroquinone to any type of cancer in humans.25–27 It is important to highlight that because of this ban, access to OTC HQ was limited and impacts patients with dyschromia with limited resources or those who don’t have the opportunity to see a provider.

Retinoids. MOA. All-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA), 13-cis-retinoic acid (isotretinoin), retinol, retinaldehyde, tazarotene and adapalene are believed to function as pigment-lightening agents based on their ability to inhibit tyrosinase, decrease melanin transfer, accelerate cell turn-over of keratinocytes, increase permeability in the stratum corneum, and ultimately disperse melanin.28

Tretinoin (ATRA). Several recent studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of topical RA cream for the treatment of photodamage, but minimal studies include melasma. Three clinical trials were conducted in 300 Hispanic patients to look for the ideal concentration of HQ (ranging in concentration from 2%-5%) with or without ATRA (ranging in concentration from 0.05%-0.1%) in addition to concomitant broad-spectrum sunscreen. Color photographs and clinical evaluations were obtained before treatment and after six weeks of treatment showing more than 50-percent improvement with a combination therapy of ATRA 0.05% to 0.1% and HQ 2%. Using ATRA with a low concentration of HQ increased the effectiveness of HQ 2% use alone and reduced the unpleasant side effects reported with higher concentrations of HQ.29 In two double blinded, vehicle-controlled RCTs, 38 Caucasians and 28 African Americans were treated with ATRA 0.1% cream versus placebo daily for 40 weeks.30, 31 Investigators found statistically significant improvement in severity with ATRA 0.1% treatment regimen compared to placebo after 40 weeks of treatment in Caucasians, improvement in pigmentation was noted by Week 24, a statistically difference was revealed showing clinical lightening following ATRA treatment versus placebo.31 However, in the African American group, results only revealed marginal statistical significance.30 A recent single-center, single-blinded study evaluated the efficacy of HQ 4% plus ATRA 0.02% cream for 24 weeks in 39 female patients with mild to moderate epidermal melasma. A statistically significant reduction in MASI scores starting at Week 4 through Week 24 was reported, where 87.9 percent of patients reported satisfaction on effectiveness and improved QoL.32

Retinaldehyde (RAL). No studies evaluating its efficacy as monotherapy for melasma were found.

Isotretinoin (ISO). A RCT, 40-week study was done with thirty Thai patients with moderate to severe melasma in which a group applied daily ISO 0.05% gel and another group applied a placebo mixed with broad spectrum sunscreen daily. According to MASI and colorimetry measurement, no statistically significant difference between both groups were found. This study did show that the use of broad-spectrum sunscreen alone had a significant lightening effect in the Thai patients.33

Tazarotene (TAZ). No studies for the efficacy of tazarotene as monotherapy for melasma was found.

Adapalene (ADP). In a preliminary report of a 14-week RCT, the efficacy and patient satisfaction with ATRA 0.05% vs. ADP 0.1% in 30 Indian female patients with melasma was assessed. Patients in the ATRA 0.05% group demonstrated reduced MASI score by 37-percent versus 41-percent reduction with ADP 0.1%. Thus, no statistical difference between the two groups were reported.34

Retinol (ROL). A 12-week open-label study was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a new formulation of micro-entrapped HQ 4%/ ROL 0.15% formulation twice daily. Significant improvement for 39 percent, 77 percent, and 77 percent of patients at Weeks 4, 8, and 12, respectively, was reported based on colorimetry measurement and physician global assessment.34

Tolerability and side effects. Topical retinoids have shown to cause erythema, dryness and peeling while some have reported burning and stinging.29-32, 35 However, they were mostly well tolerated.34 No statistical difference between reported side effects were noted between ROL versus micro-entrapped 4% HQ, and common side effects were minimal.35 A mild transient “retinoid dermatitis” was reported in 27 percent of ISO gel treated patients for melasma.33

Triple combination (TC) therapy. MOA. Since the efficacy of the Kligman’s-Willi’s formula was demonstrated, modified triple combination cream comprised of HQ, a retinoid and a low potency steroid, is considered as a more tolerable and efficacious treatment regimen for melasma. Adding a steroid to a combination of HQ and ATRA, suppresses secretory cytokines that play a role in the activation of melanocytes for the synthesis of melanin, also reducing inflammation and skin irritation that are commonly seen with the use of HQ or retinoids.8

Efficacy/study findings. A double-blinded RCT study of 211 Chinese patients showed that TC cream composed of HQ 4%, ATRA 0.05% and fluocinolone acetonide (FA) 0.01% was more effective in clearing melasma at Week 8 compared to placebo based on a decreased index of total target score (DITTS).36 A 119-patient, open-labeled RCT found that once-daily application of TC cream (HQ 4%, RA 0.05% and FA 0.01%) had a 35 percent clearance rate versus 5.1 percent when solely applying HQ 4% twice daily for eight weeks. In addition, a significant improvement of >75% was achieved at Week 4 based on investigator grade assessment (IGA) for 73 percent of patients applying TC cream and 49 percent for those applying HQ cream alone.37 A larger single-blinded RCT was conducted with 242 patients to evaluate the same regimen and showed an improvement using TC cream for 64.2 percent of patients versus 39.4 percent of patients using HQ 4%. A statistically significant reduction in MASI was superior at Week 4 and 8 with TC cream. Interestingly, the difference in efficacy between TC and HQ increased in individuals with darker skin types and those with mixed type melasma.38 A 12-week, double-blinded RCT of 64 patients revealed good to excellent overall improvement for 81.2 percent of patients using TC cream (HQ 4%, RA 0.05%, and dexamethasone 0.05%) compared to 31.3 percent of patients treated with HQ 4% based on IGA.39 Moreover, in two eight-week, multicenter RCTs, 641 patients were evaluated and compared a hydrophilic TC cream (HQ 4%, RA 0.05%, FA 0.01%) with three dual combination agents composed of RA+HQ, RA+FA, and HQ+FA. A 75-percent reduction in pigmentation was found in >70 percent of patients treated with TC cream compared with 30 percent of patients treated with dual combination. Additionally, 77 percent experienced complete or near-complete clearance when compared with dual therapy, where percentage clearances were much less.40

Tolerability and side effects. TC cream has not only shown to be efficacious but has also demonstrated to be a safe choice when used daily for eight weeks, followed by a maintenance phase of intermittent application (twice weekly or tapering regimen) for six months.35 Erythema and scaling is the most common side effect. Less common side effects are dryness, burning sensation, and pruritus. Throughout our search, we only found two patients reporting skin atrophy, one applying HQ + FA for eight weeks and another in the maintenance phase regimen of twice weekly application of TC.40, 41 A frequent yet mild systemic adverse effect that was reported was headache.37 Some patients reported telangiectasias, however these already had a history of it at baseline; it is important to note this can occur as a result of prolonged steroid use.41

Corticosteroids. Corticosteroids play a role directly in UV-B inducing melanogenesis due to its properties of inhibiting prostaglandins and cytokines, such as endothelin 1 and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), these play a role in increasing melanin production.42 As a depigmenting monotherapy agent, minimal efficacy has been shown and can carry the risk of developing epidermal atrophy, telangiectasias, acne, rosacea-like erythema, and perioral dermatitis.43 Consequently, corticosteroids as monotherapy are usually combined with other topical agents for the treatment of melasma.

Ascorbic acid. MOA. Ascorbic acid, a well-known antioxidant binds to copper, inhibiting tyrosinase, and suppresses oxidative polymerization of melanin intermediates, inhibiting melanin production in the melanogenesis pathway.42

Efficacy/study findings. In a double-blinded RCT of 16 patients with melasma treated with HQ 4% versus L-ascorbic acid 5% (daily application, split-face study) for 16 weeks, 62.5 percent of patients reported good to excellent results with L-ascorbic acid 5%. These results were seen at the third month of treatment whereas patients treated with HQ 4% saw more significant results as early as the first month. No statistically significant difference was noticed between both regimens based on colorimetry measurements.44 In an open-label trial done on 39 patients in Korea using L-ascorbic acid 25% twice daily in combination with a chemical solvent for enhancing penetration (Nmethyl-2-pyrrolidone and dimethyl isosorbide), a statistically significant decrease from baseline to Week 16 was seen according to MASI values and mexameter results. Melasma Quality of Life Scale (MelasQol) scores indicated improved quality of life.45

Tolerability and side effects. In the two studies mentioned before, different concentrations were used, demonstrating that higher concentrations result in more side effects. Only 6.25 percent of patients with melasma treated with L-ascorbic acid 5% developed irritation versus 68.75 percent of patients treated with HQ 4% reporting irritation. No other adverse effects were reported.44 In the study using L-ascorbic acid 25%, some patients reported erythema, scaling, or a mild to moderate burning. These were mild and disappeared within two weeks.45 Ascorbic acid was shown to be well-tolerated and significantly less irritating than HQ 4%.44

Azelaic acid (AZA). MOA. AZA, a natural dicarboxylic acid previously used as an adjuvant treatment for melanoma due to its anti-proliferative and cytotoxic effects on abnormal melanocytes, has been studied as a depigmenting agent for the treatment of melasma.46 Studies have shown it competitively inhibits tyrosinase and has inhibitory effects on reactive oxygen species that play a role in the melanogenesis pathway.8, 46

Efficacy/study findings. In a 24-week, multicenter, controlled, double blinded clinical trial with 329 women, the efficacy of AZA 20% cream was compared to HQ 4% cream for treating melasma. No significant difference was shown between both treatments, 65 percent of the patients treated with AZA 20% were reported to achieve good to excellent results compared to 73 percent of patients with HQ 4%.47 A smaller open trial study of 29 women with mild melasma, also compared the efficacy of AZA 20% cream versus HQ 4% cream both used twice daily in addition to a broad-spectrum sunscreen for two months. According to MASI scores, a statistically significant decrease after the first and second month of therapy with both treatments were reported. Comparison between the two groups revealed a significant difference showing better results with AZA in the second month.48 An open-label study evaluated different concentrations of glycolic acid (GA) peels as an adjuvant with AZA 20% versus AZA 20% alone. This study reported a superior statistically significance decrease in MASI score with 20% AZA and GA peel from Week 12 and on, enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of topical AZA cream.49 AZA cream as monotherapy, at concentrations of 15%-20%, has shown greater efficacy than 2% HQ, however it has not demonstrated to be superior to 4% HQ.47

Tolerability and side effects. AZA 20% seems to be well tolerated in patients. The most prominent side effect reported was localized pruritus, followed by erythema, and irritation.47 There was no statistically significant difference between adverse effects when adding a GA peel compared to using AZA 20% cream alone. Adverse effects were only temporary, and discontinuation of treatment was not necessary.49 A study revealed that 46.6 percent of patients experienced erythema at the first month with HQ 4% cream versus 7.3% with AZA 20%. The acute side effects previously reported diminished after the second month.48

Glycolic acid (GA). MOA. GA is an alpha-hydroxy acid (AHA) which causes disruption in cell-adhesion, resulting in desquamation, and inhibits tyrosinase activity, suppressing melanin production.9

Efficacy/study findings. Many studies have demonstrated not only that GA peels can enhance the efficacy of topical agents, especially in darker skin types, but have shown increased efficacy in shorter amounts of time. We did not find any head-to-head studies comparing GA with HQ, they are usually used as adjuvant therapy.9 In a single-blinded split-faced RCT, the efficacy of performing 20-30% concentration of GA peels every two weeks, in addition to HQ 4% cream twice daily and sunscreen to the entire face was studied in 21 Hispanic women with melasma. Statistically significant reduction in MASI score and mexameter measurements were shown in both groups after Week 8 compared to baseline, with no difference between groups. However, based on the IGA and patient’s feedback, a slightly better improvement was reported with the addition of GA peels.50 A single-blinded RCT divided 100 patients in five different groups and were treated with a cream formula. The following combinations were studied: HQ 4%, as monotherapy, HQ 4% + GA 10%, HQ 4% + hyaluronic acid (HA) 0.01%, HQ 4% + GA 10% + HA 0.01%, and a placebo group. The most significant decrease in melasma was seen in the group treated with HQ + GA + HA reporting the highest efficacy of 79.25 percent according to MASI score, tolerable side effects, and no signs of recurrence following strict sun avoidance.51

Tolerability and side effects. In the studies previously discussed, mild-to moderate erythema, pruritus or inflammation were reported.50, 51 GA 20% showed greater efficacy when used as adjuvant with HQ 4% but has been reported to be more irritating to the skin than using HQ alone. Patients should also be made aware of the risk of some desquamation. Adding moisturizing agents helps in minimizing this undesirable side effect.51 It’s important to mention the potential risk of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation reported with GA peels especially in darker skin types.1, 52

Kojic acid (KA). MOA. KA, a natural fungal metabolite found in Asian foods, has been studied as a cosmeceutical product due to its lightening benefits by chelating divalent ions, trapping free-radicals and inhibiting tyrosinase. It also has anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, photo-protective, and anti-bacterial properties.13,53

Efficacy/study findings. The efficacy of different concentrations of KA alone as well as in combinations with other topical agents has been reported. In an RCT, 80 patients received KA 1% alone or in combination with 2% HQ and/or a potent steroid for 12 weeks. The greatest decrease in MASI score (71.87%) was reported with the combination of KA 1%, HQ 2%, and betamethasone valerate cream.53 In a study of 60 patients treated nightly with HQ 4% cream or a KA combination cream (KA 0.75% and ascorbic acid 2.5%), both groups showed a reduction in MASI score from Week 4 to Week 12. However, the 4% HQ cream group had a greater statistically significant efficacy than KA combination cream from Week 0 to Week 12.54

Tolerability and side effects. Studies have shown concentrations of KA of 1% or less to be safe and tolerable for a period of three months to two years, with no significant side effects. The most common adverse reaction seen with KA is irritant contact dermatitis; accompanied by localized irritation, edema, pruritus, and pain.53, 54

Salicylic acid (SA). MOA. SA is a B-hydroxy acid, lipid-soluble agent commonly used in cosmetic formulations as a peeling agent for skin lightening due to its keratolytic properties. It is well known for its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory properties.55

Efficacy/study findings. A small prospective RCT compared the efficacy of SA 20% -30% peels every two weeks for up to eight weeks in combination with HQ 4% twice daily for 14 weeks, versus HQ 4% only. A statistically significant improvement according to MASI score and spectrophotometer in both regimens was reported, but no difference in efficacy between them was reported.56 In a double-blinded RCT, 52 female patients with melasma participated to compare the efficacy and tolerability of a topical formulation containing ellagic acid 0.5% and salicylic acid 0.1% vs. 4% HQ cream twice daily for 12 weeks. Clinical and colorimetric severity improvement was reported with combination therapy, still favoring 4% HQ as topical therapy for melasma.57

Tolerability and side effects. SA for the therapy of melasma can present with side effects that include erythema, burning sensation, irritation, peeling, blistering, or crusting.56, 57 These are similar to those seen with GA. In the studies previously discussed, side effects were well-tolerated and most predominantly seen at Week 6.56 Overall, SA along with sunscreen and in combination with some topical agents is considered to be well-tolerated.

Niacinamide. MOA. Niacinamide (vitamin B3) is the biologically active form of niacin which is believed to decrease pigmentation by downregulating melanosomes transferred from melanocytes to keratinocytes decreasing the accumulation of melanin in the skin. Not only can it reduce pigmentation, but it is also known to reduce inflammation and solar degenerative changes.46,58

Efficacy/study findings. In a double blinded study of 27 patients with melasma, the efficacy of niacinamide 4% cream was compared to HQ 4%, MASI score decreases were 62 percent and 70 percent respectively after eight weeks of treatment. Clinical photographs and colorimetric measures showed a statistically significant improvement, but no statistically significant difference between both regimens.53 A prospective, single arm, open-label study of 33 patients evaluated the efficacy of a novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1% and RAL 0.05% and demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in MASI score compared to baseline from Week 4 to Week 8.11 Furthermore, a double-blinded study showed 4% niacinamide have better results in decreasing MASI score when compared to ATRA 0.05%.60

Tolerability and side effects. Topical niacinamide is known to be a good and safe therapeutic choice for the treatment of melasma.40 Adverse reactions with the use of topical niacinamide are mostly mild burning, erythema, and pruritus. These can improve with the continued use of the topical agent.58 In the study discussed above, 18 percent of patients reported side effects with the use of topical niacinamide versus 29 percent of patients treated with HQ cream.59 With the novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1% and RAL 0.05%, 69.7 % of participant’s experienced adverse effects. These were mostly described as a well-tolerated burning sensation.11

Tranexamic acid (TXA). MOA. TXA, a trans-4-aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid has been used for many years as an anti-fibrolytic agent commonly to treat heavy bleedings during menstruation. Recently, studies have shown promising results as an alternative treatment for melasma due to its ability to inhibit plasminogen activator (PA) and interfere in the plasminogen/plasmin pathway; subsequently decreasing melanogenic factors such as prostaglandins, leukotrienes, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (a-MSH).61, 62 In addition, a study showed TXA to slightly decrease the number of CD 31+ blood vessels and downregulate endothelin-1, a melanogenic factor that induces pigmentation.63 A study in guinea pigs showed it can also inhibit tyrosinase activity.64

Efficacy/study findings. The efficacy of TXA 2% cream in an emulsion and lotion vehicle for the treatment of melasma was evaluated showing a statistically significant improvement at Week 4 and 8 according to MASI score.63 A 39 patient double-blind split-face trial study found that application of twice daily TXA 3% cream for 12 weeks was as effective as a solution of HQ 3% + dexamethasone 0.01% based on a statistically significant decreased in MASI score and clinical photographs for both therapies, without any differences between them based on efficacy.62 Another double-blinded RCT of 60 women with melasma, assessed the efficacy of TXA 5% cream, a higher concentration than the previous study, versus HQ 2% cream alone both applied twice daily for 12 weeks. Both regimens showed improvement according to MASI score, but no significant difference was found between them.65 A double-blinded split-face trial evaluated the efficacy of TXA 5% as a liposomal vehicle vs. HQ 4% cream which showed a statistically significant reduction in MASI score on week 12. Although a greater reduction in MASI score was seen with liposomal TXA 5%, no statistically difference between both treatments was reported.66

Tolerability and side effects. Topical TXA has been shown to be a well-tolerated topical agent for melasma with no reported adverse effects to date, oral tranexamic, not being discussed in this article, does carry a risk of thrombosis, nausea, diarrhea, and stomach aches.62, 63, 65

Cysteamine. MOA. Cysteamine is an aminothiol, product of the natural degradation of L-cysteine, with intrinsic antioxidant properties. Its depigmenting properties were shown long ago on black goldfish, as well as in a study done with black guinea pig skin, it showed the ability to inhibit tyrosinase activity and decrease melanocyte function resulting in a reduction in melanin production.67

Efficacy/study findings. In a double-blinded RCT, the efficacy of daily cysteamine 5% cream vs. placebo for the treatment of melasma was assessed in 50 patients throughout a four-month period. According to dermacatch (a skin colorimetric measurement tool) a significant difference between both groups at Month 2 was reported, where cysteamine 5% was superior in efficacy.12 In another double-blinded RCT, 50 patients were evaluated to compare the efficacy of cysteamine 5% (applied daily for only 15 minutes) vs. a Modified Kligman’s formula (MKF: HQ 4% + RA 0.05% + betamethasone 0.1%) applied nightly for 16 weeks. The cysteamine treatment showed a decrease in MASI score comparable to the MKF treated group that was strongly statistically significant at Week 8 and 16. However, according to the IGA and the patient’s assessments, the differences between the two regimens were not statistically significant.68

Tolerability and side effects. Overall, a minority of the patients treated with cysteamine cream reported erythema, dryness, pruritus, dyspigmentation (hypo or hyperpigmentation), burning and/or irritation; mostly reported as mild, and better tolerated than TC cream. Repeated use of the agent resolved these mild adverse effects.12,67,68 Some complained about the odor of the cream, but they did not require discontinuation of cream.

Other Topical Agents. Cosmeceuticals for skin lightening have become popular as they can be used alone or in combination with other established prescribed depigmenting agents. They also can target several steps in the melanogenesis pathway. Although with less evidence than other treatments, some studies have demonstrated their efficacy and tolerability. Some of these topical formulations contain agents such as thiamidol, arbutin, linoleic acid, phytic acid, yeast extract, mulberry extract oil, rucinol, 2% undecylenoyl phenylalanine, and a newer study with epidermal growth factors has also been reported.3, 8, 69-73

A randomized, double-blinded, split-face study compared the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of a non-hydroquinone cosmetic topical brightener (CTB) versus 4% hydroquinone applied twice daily for a period of 12 weeks. The active ingredients of CTB, which are tranexamic acid, phenylethyl resorcinol, niacinamide, and tetrapeptide-30 (SkinMedica Inc., NY), showed a statistically significant decrease in MASI and clinical photographs, as well as MelasQoL. Both regimens showed no significant difference between them, as both were effective and well-tolerated.74 A 12-week, single-center, clinical study evaluated the safety and efficacy of a novel topical facial serum containing 3% tranexamic acid, 1% kojic acid, and 5% niacinamide (SkinCeuticals Inc., New York). Statistically significant improvement was reported as early as Week 2 based on a modified MASI scale, standardized digital photography, colorimeter and subjects’ self-assessment questionnaires. Overall, satisfaction was reported in over 90 percent of patients, with only minimal irritation seen which resolved quickly after application.75 In another 12-week single-center, open-label, prospective study a formula composed of 10% glycolic acid, 2% phytic acid, and 1% soothing complex of jojoba and sunflower seed (SkinCeuticals, Inc.) was demonstrated to be significantly effective according to expert clinical grading and self-assessment questionnaires starting in Week 4. In addition, no adverse effects were reported after three months of treatment.76 In a single-center investigator blinded, 12-week study, the efficacy of the twice-daily application of a novel formulation containing hydroxyphenoxy propionic acid, ellagic acid, yeast extract, and salicylic acid (SkinCeuticals Inc., New York) was compared to a prescription treatment of 4% hydroquinone cream and 0.025% tretinoin cream (HQ/RA). The investigator assessments showed statistically significant improvement with both groups, at Week 4, with superior improvement with the novel formulation. However, no statistically significant difference was seen between both groups by Week 12. Patients did report more tolerability with the novel formulation indicating less erythema, dryness, and peeling.77 Moreover, a 20-week study for a skin lightening agent (SkinCeuticals, Inc., New York) with twice-daily application following the discontinuation of 4% hydroquinone/0.025% tretinoin prescription therapy after 12 weeks of use was done. According to corneometry measurements and clinical photography, statistically significant improvement of pigmentation was seen at Week 12 and Week 20.78 In two previous 12-week clinical studies, the efficacy and tolerability of a 5% skin lightening complex composed of four skin-brightening actives (disodium glycerophosphate, L-leucine, phenylethyl resorcinol, and undecylenoyl phenylalanine)(Neocutis, Inc.) was tested. A statistically significant decrease in MASI score was seen, demonstrating its efficacy and well-tolerability as a depigmenting agent for melasma.79, 80

Conclusion

The main goal of topical therapy is to diminish the appearance of hyperpigmented lesions, decrease pigment production, and to ultimately prevent recurrence. More studies are currently coming out regarding the vascular component of melasma, however that is out of scope of the discussion of this paper. As stated before, sunscreen is strictly essential. Figure 2 and Figure 3 provide the varying mechanisms of actions of the agents discussed and how they interact in the melanin pathway.

There are a wide range of treatments available, and response may vary by patient. Triple combination therapy continues to be the gold standard of care. This regimen has shown to carry the risk of potential ochronosis but most commonly irritant contact dermatitis. It is important to mention that erythema and scaling caused by this irritant dermatitis could potentially worsen the hyperpigmentation and aggravate the person’s condition. However, it is the role of the physician to monitor the patient closely and treat adverse events while providing the patient with an appropriate regimen. Cysteamine and topical tranexamic acid are newer options that physicians can incorporate into their arsenal; and both have been shown to have adequate scientific evidence, although further and larger studies are needed. Cysteamine has no known severe adverse effects, and thus is an alternate treatment. It can be used as either primary or adjuvant treatment and could serve as a potential agent in the maintenance phase since triple combination cream is not a long-term option. Oral TA does have strong evidence-based recommendation, although it does carry a theoretical risk of thrombosis. Other agents such as kojic acid, niacinamide, glycolic acid, and azelaic acid have a lower risk for adverse events. More evidence is needed in order to assess their relative and individual benefits as well as optimal formulations. These agents are a great option for adjunct treatments, to be used in combination with other HQ modalities be it in combination in compounding or as an addition to the patient’s regiment. They’re also a good option for the maintenance phase of melasma treatment as well.

Combination treatments are necessary to achieve optimal results. Knowledge of the precise mechanism of action of the agents mentioned above is optimal in order for adequate selection of treatment which depends on the severity and type of melasma. This knowledge can lead to efficacious and reproducible results. More studies are needed to determine the appropriate combination of these agents and which of these combination therapies could result in a superior therapeutic strategy for this patient population.

References

- McKesey J, Tovar-Garza A, Pandya AG. Melasma Treatment: An Evidence-Based Review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020 Apr;21(2):173–225.

- Vachiramon V, Suchonwanit P, Thadanipon K. Melasma in men. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012 Jun;11(2):151–157.

- Huerth KA, Hassan S, Callender VD. Therapeutic Insights in Melasma and Hyperpigmentation Management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Aug 1;18(8):718–729.

- Sarkar R, Arora P, Garg VK, et al. Melasma update. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014 Oct;5(4):426–435.

- Ortonne JP, Arellano I, Berneburg M, et al. A global survey of the role of ultraviolet radiation and hormonal influences in the development of melasma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009 Nov;23(11):1254–1262.

- Pawaskar MD, Parikh P, Markowski T, et al. Melasma and its impact on health-related quality of life in Hispanic women. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18(1):5-9.

- Jiang J, Akinseye O, Tovar-Garza A, et al. The effect of melasma on self-esteem: A pilot study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017 Dec 8;4(1):38–42.

- Gupta AK, Gover MD, Nouri K, et al. The treatment of melasma: a review of clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Dec;55(6):1048–1065.

- Austin E, Nguyen JK, Jagdeo J. Topical Treatments for Melasma: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Nov 1;18(11):S1545961619P1156X.

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad TF, et al. The Role of Sunscreen in Melasma and Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2020 Jan-Feb;65(1):5–10.

- Crocco EI, Veasey JV, Boin MF, et al. A novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05% for treatment of epidermal melasma. Cutis. 2015 Nov;96(5):337–342.

- Farshi S, Mansouri P, Kasraee B. Efficacy of cysteamine cream in the treatment of epidermal melasma, evaluating by Dermacatch as a new measurement method: a randomized double blind placebo controlled study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018 Mar;29(2):182–189. Erratum in: J Dermatolog Treat. 2020 Feb;31(1):104.

- Grimes PE, Ijaz S, Nashawati R, Kwak D. New oral and topical approaches for the treatment of melasma. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018 Nov 20;5(1):30–36.

- Taraz M, Niknam S, Ehsani AH. Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: A comprehensive review of clinical studies. Dermatol Ther. 2017 May;30(3).

- Jimbow K, Obata H, Pathak MA, et al. Mechanism of depigmentation by hydroquinone. J Invest Dermatol.1974 Apr;62(4):436–449.

- Nordlund JJ, Grimes PE, Ortonne JP. The safety of hydroquinone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006 Aug;20(7):781–787.

- Tirado-Sánchez A, Santamaría-Román A, Ponce-Olivera RM. Efficacy of dioic acid compared with hydroquinone in the treatment of melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2009 Aug;48(8):893–895.

- Haddad AL, Matos LF, Brunstein F, et al. A clinical, prospective, randomized, double-blind trial comparing skin whitening complex with hydroquinone vs. placebo in the treatment of melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2003 Feb;42(2):153–156.

- Khosravan S, Alami A, Mohammadzadeh-Moghadam H, et al. The Effect of Topical Use of Petroselinum Crispum (Parsley) Versus That of Hydroquinone Cream on Reduction of Epidermal Melasma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Holist Nurs Pract. 2017 Jan/Feb;31(1):16–20.

- Taghavi F, Banihashemi M, Zabolinejad N, et al. Comparison of therapeutic effects of conventional and liposomal form of 4% topical hydroquinone in patients with melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019 Jun;18(3):870–873.

- Prignano F, Ortonne JP, Buggiani G, et al. Therapeutical approaches in melasma. Dermatol Clin. 2007 Jul;25(3):337–342.

- Nordlund JJ. Hydroquinone: Its value and safety. commentary on the US FDA proposal to remove hydroquinone from the over-the-counter market. Expert Review of Dermatology. 2007;2(3):283–287.

- Levitt J. The safety of hydroquinone: a dermatologist’s response to the 2006 Federal Register. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Nov;57(5):854–872.

- Nanda S, Grover C, Reddy BS. Efficacy of hydroquinone (2%) versus tretinoin (0.025%) as adjunct topical agents for chemical peeling in patients of melasma. Dermatol Surg. 2004 Mar;30(3):385–389.

- McGregor D. Hydroquinone: an evaluation of the human risks from its carcinogenic and mutagenic properties. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2007;37(10):887–914.

- North M, Shuga J, Fromowitz M, Loguinov A, Shannon K, Zhang L, Smith MT, Vulpe CD. Modulation of Ras signaling alters the toxicity of hydroquinone, a benzene metabolite and component of cigarette smoke. BMC Cancer. 2014 Jan 5;14:6.

- Yang X, Lu Y, He F, et al. Benzene metabolite hydroquinone promotes DNA homologous recombination repair via the NF-κB pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2019 Aug 22;40(8):1021–1030.

- Ortonne JP. Retinoid therapy of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2006 Sep-Oct;19(5):280–288.

- Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB, Kraus EW. Usefulness of retinoic acid in the treatment of melasma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986 Oct;15(4 Pt 2):894–899.

- Kimbrough-Green CK, Griffiths CE, Finkel LJ, et al. Topical retinoic acid (tretinoin) for melasma in black patients. A vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 1994 Jun;130(6):727–733.

- Griffiths CE, Finkel LJ, Ditre CM, et al. Topical tretinoin (retinoic acid) improves melasma. A vehicle-controlled, clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 1993 Oct;129(4):415–421.

- Rendon M, Dryer L. Investigator-Blinded, Single-Center Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Tolerability of a 4% Hydroquinone Skin Care System Plus 0.02% Tretinoin Cream in Mild-to-Moderate Melasma and Photodamage. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016 Apr;15(4):466–475.

- Leenutaphong V, Nettakul A, Rattanasuwon P. Topical isotretinoin for melasma in Thai patients: a vehicle-controlled clinical trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 1999 Sep;82(9):868–875.

- Dogra S, Kanwar AJ, Parsad D. Adapalene in the treatment of melasma: a preliminary report. J Dermatol. 2002 Aug;29(8):539–540.

- Grimes PE. A microsponge formulation of hydroquinone 4% and retinol 0.15% in the treatment of melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Cutis. 2004 Dec;74(6):362–368.

- Gong Z, Lai W, Zhao G,et al. Efficacy and safety of fluocinolone acetonide, hydroquinone, and tretinoin cream in chinese patients with melasma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, parallel-group study. Clin Drug Investig. 2015 Jun;35(6):385–395.

- Ferreira Cestari T, Hassun K, Sittart A, et al. A comparison of triple combination cream and hydroquinone 4% cream for the treatment of moderate to severe facial melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007 Mar;6(1):36–39.

- Chan R, Park KC, Lee MH, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of a fixed triple combination (fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%, hydroquinone 4%, tretinoin 0.05%) compared with hydroquinone 4% cream in Asian patients with moderate to severe melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Sep;159(3):697–703.

- Astaneh R, Farboud E, Nazemi MJ. 4% hydroquinone versus 4% hydroquinone, 0.05% dexamethasone and 0.05% tretinoin in the treatment of melasma: a comparative study. Int J Dermatol. 2005 Jul;44(7):599–601.

- Taylor SC, Torok H, Jones T, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new triple-combination agent for the treatment of facial melasma. Cutis. 2003 Jul;72(1):67–72.

- Arellano I, Cestari T, Ocampo-Candiani J, et al. Preventing melasma recurrence: prescribing a maintenance regimen with an effective triple combination cream based on long-standing clinical severity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012 May;26(5):611-618.

- Ebanks JP, Wickett RR, Boissy RE. Mechanisms regulating skin pigmentation: the rise and fall of complexion coloration. Int J Mol Sci. 2009 Sep 15;10(9):4066–4087.

- Menter A. Rationale for the use of topical corticosteroids in melasma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004 Mar-Apr;3(2):169-174.

- Espinal-Perez LE, Moncada B, Castanedo-Cazares JP. A double-blind randomized trial of 5% ascorbic acid vs. 4% hydroquinone in melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2004 Aug;43(8): 604–607.

- Hwang SW, Oh DJ, Lee D, et al. Clinical efficacy of 25% L-ascorbic acid (C’ensil) in the treatment of melasma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009 Mar-Apr;13(2):74–81.

- Bandyopadhyay D. Topical treatment of melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54(4): 303–309.

- Baliña LM, Graupe K. The treatment of melasma. 20% azelaic acid versus 4% hydroquinone cream. Int J Dermatol.1991 Dec;30(12):893–895.

- Farshi S. Comparative study of therapeutic effects of 20% azelaic acid and hydroquinone 4% cream in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol.

- Dayal S, Sahu P, Dua R. Combination of glycolic acid peel and topical 20% azelaic acid cream in melasma patients: efficacy and improvement in quality of life. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017 Mar;16(1):35–42.

- Hurley ME, Guevara IL, Gonzales RM, et al. Efficacy of glycolic acid peels in the treatment of melasma. Arch Dermatol. 2002 Dec;138(12):1578–1582.

- Ibrahim ZA, Gheida SF, El Maghraby GM, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of combinations of hydroquinone, glycolic acid, and hyaluronic acid in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015 Jun;14(2):113–123.

- Sarkar R, Bansal S, Garg VK. Chemical peels for melasma in dark-skinned patients. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012 Oct;5(4):247–253.

- Saeedi M, Eslamifar M, Khezri K. Kojic acid applications in cosmetic and pharmaceutical preparations. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019 Feb;110:582–593.

- Monteiro RC, Kishore BN, Bhat RM, et al. A Comparative Study of the Efficacy of 4% Hydroquinone vs 0.75% Kojic Acid Cream in the Treatment of Facial Melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2013 Mar;58(2):157.

- Kornhauser A, Coelho SG, Hearing VJ. Applications of hydroxy acids: classification, mechanisms, and photoactivity. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010 Nov 24;3:135–142.

- Kodali S, Guevara IL, Carrigan CR, et al. A prospective, randomized, split-face, controlled trial of salicylic acid peels in the treatment of melasma in Latin American women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Dec;63(6):1030–1035.

- Dahl A, Yatskayer M, Raab S, et al. Tolerance and efficacy of a product containing ellagic and salicylic acids in reducing hyperpigmentation and dark spots in comparison with 4% hydroquinone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013 Jan;12(1):52-58.

- Rolfe HM. A review of nicotinamide: treatment of skin diseases and potential side effects. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Dec;13(4):324–328.

- Navarrete-Solís J, Castanedo-Cázares JP, Torres-Álvarez B, et al. A Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial of Niacinamide 4% versus Hydroquinone 4% in the Treatment of Melasma. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:379173.

- Campuzano-García AE, Torres-Alvarez B, Hernández-Blanco D, et al. DNA Methyltransferases in Malar Melasma and Their Modification by Sunscreen in Combination with 4% Niacinamide, 0.05% Retinoic Acid, or Placebo. Biomed Res Int. 2019 Apr 22;2019:9068314.

- Kanechorn Na Ayuthaya P, Niumphradit N, Manosroi A, et al. Topical 5% tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma in Asians: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2012 Jun;14(3):150–154.

- Ebrahimi B, Naeini FF. Topical tranexamic acid as a promising treatment for melasma. J Res Med Sci. 2014 Aug;19(8):753–757.

- Kim SJ, Park JY, Shibata T, et al. Efficacy and possible mechanisms of topical tranexamic acid in melasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016 Jul;41(5):480–485.

- Sheu SL. Treatment of melasma using tranexamic acid: what’s known and what’s next. Cutis. 2018 Feb;101(2):E7–E8.

- Atefi N, Dalvand B, Ghassemi M, et al. Therapeutic Effects of Topical Tranexamic Acid in Comparison with Hydroquinone in Treatment of Women with Melasma. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017 Sep;7(3):417–424.

- Banihashemi M, Zabolinejad N, Jaafari MR, Salehi M, et al. Comparison of therapeutic effects of liposomal Tranexamic Acid and conventional Hydroquinone on melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015 Sep;14(3):174-7.

- Kasraee B, Mansouri P, Farshi S. Significant therapeutic response to cysteamine cream in a melasma patient resistant to Kligman’s formula. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019 Feb;18(1):293–295.

- Karrabi M, David J, Sahebkar M. Clinical evaluation of efficacy, safety and tolerability of cysteamine 5% cream in comparison with modified Kligman’s formula in subjects with epidermal melasma: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial study. Skin Res Technol. 2021 Jan;27(1):24-31.

- Alvin G, Catambay N, Vergara A, et al. A comparative study of the safety and efficacy of 75% mulberry (Morus alba) extract oil versus placebo as a topical treatment for melasma: a randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011 Sep;10(9):1025–1031.

- Lee MH, Kim HJ, Ha DJ, et al. Therapeutic effect of topical application of linoleic acid and lincomycin in combination with betamethasone valerate in melasma patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2002 Aug;17(4):518–523.

- Khemis A, Kaiafa A, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of rucinol serum in patients with melasma: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2007 May;156(5):997–1004.

- Katoulis A, Alevizou A, Soura E, et al. A double-blind vehicle-controlled study of a preparation containing undecylenoyl phenylalanine 2% in the treatment of melasma in females. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Jun;13(2):86–90.

- Lyons A, Stoll J, Moy R. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Split-Face Study of the Efficacy of Topical Epidermal Growth Factor for the Treatment of Melasma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Sep 1;17(9):970–973.

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Randomized, Double-Blinded, Split-Face Study Comparing the Efficacy and Tolerability of Two Topical Products for Melasma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020 Sep 1;19(9):822–827.

- Desai S, Ayres E, Bak H, et al. Effect of a Tranexamic Acid, Kojic Acid, and Niacinamide Containing Serum on Facial Dyschromia: A Clinical Evaluation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 May 1;18(5):454-459.

- Houshmand EB. Effect of glycolic acid, phytic acid, soothing complex containing Emulsion on Hyperpigmentation and skin luminosity: A clinical evaluation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021 Mar;20(3):776–780.

- Draelos Z, Dahl A, Yatskayer M, et al. Dyspigmentation, skin physiology, and a novel approach to skin lightening. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013 Dec;12(4):247–253.

- Draelos ZD, Raab S, Yatskayer M, et al. A method for maintaining the clinical results of 4% hydroquinone and 0.025% tretinoin with a cosmeceutical formulation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015 Apr;14(4):386-390.

- Gold MH, Biron J. Efficacy of a novel hydroquinone-free skin-brightening cream in patients with melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011 Sep;10(3):189–196.

- Dreher F, Draelos ZD, Gold MH, et al. Puissegur Lupo ML. Efficacy of hydroquinone-free skin-lightening cream for photoaging. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013 Mar;12(1):12–17.