J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(9):21–27

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(9):21–27

by Amit Om, MD, and Anjali Om, BA

Dr. Om is with the Division of Dermatology at Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida. Ms. Om is a first-year medical student at Emory School of Medicine, Emory University, in Atlanta, Georgia.

Funding: No funding was provided for this study

Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: The objectives of this review are to demonstrate that portraits, in their visual reflections of subjects faces and expressions, offer significant representations relevant to the field of dermatology and bring attention to an underappreciated aesthetic of dermatological conditions. The review comprises paintings that purposefully or inadvertently depict dermatological conditions. The findings were substantiated by searching PubMed using the keywords art, painting, and dermatology, as well as combinations of these terms. The “Notable Notes” section of JAMA Dermatology proved especially useful. The review is subdivided by disease category, including portraits that display infectious diseases, neoplastic conditions, genetic dermatoses, rosacea and/or acne, and autoimmune disorders. The breadth of examples of dermatology represented in art suggest that portraits might serve as an unintentional atlas of dermatological conditions. By implication, it seems that the arts might be more interconnected to the sciences than traditionally acknowledged.

Keywords: Art, painting, dermatology

Introduction

Art imitates life (Oscar Wilde, 1889). Across time, art has portrayed ideas, historical events, and cultural revolutions. Artists throughout history have attempted to paint their subjects as accurately as possible, and as a result, portraits have depicted cutaneous conditions, either inadvertently or purposefully. To appreciators of the visual arts, the dichotomy between realistic art (i.e., that which offers an objective perspective based on fact) and symbolic art (i.e., that which offers a subjective perspective based on emotions or aesthetics) is clear; a juxtaposition less clear, though arguably more interesting to dermatologists, is that diseases so negatively perceived by our patients can be so impartially portrayed on a canvas.

In practicing an inherently visual specialty, dermatologists should be keenly aware of aesthetics. We should also be aware of how dermatological conditions are represented and portrayed in aesthetic culture, as this could influence the way our patients perceive their diseases. In this review and presentation of portrayals of dermatological conditions within the visual arts, the artist’s canvas will become our visual exam, their designs aiding our diagnoses. These representations of dermatological conditions in art capture the reality and subtle beauty of disease.

Infectious Disease

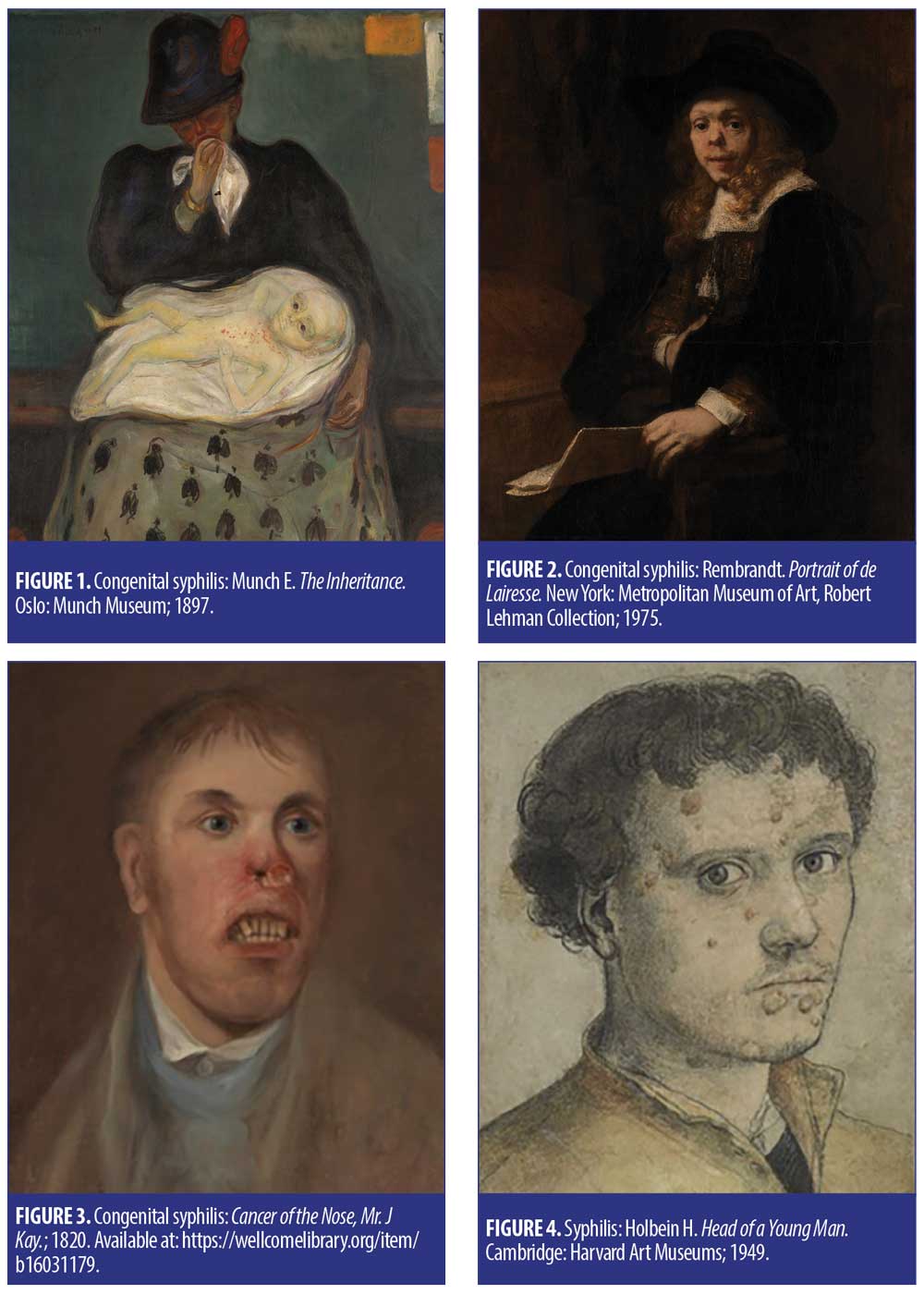

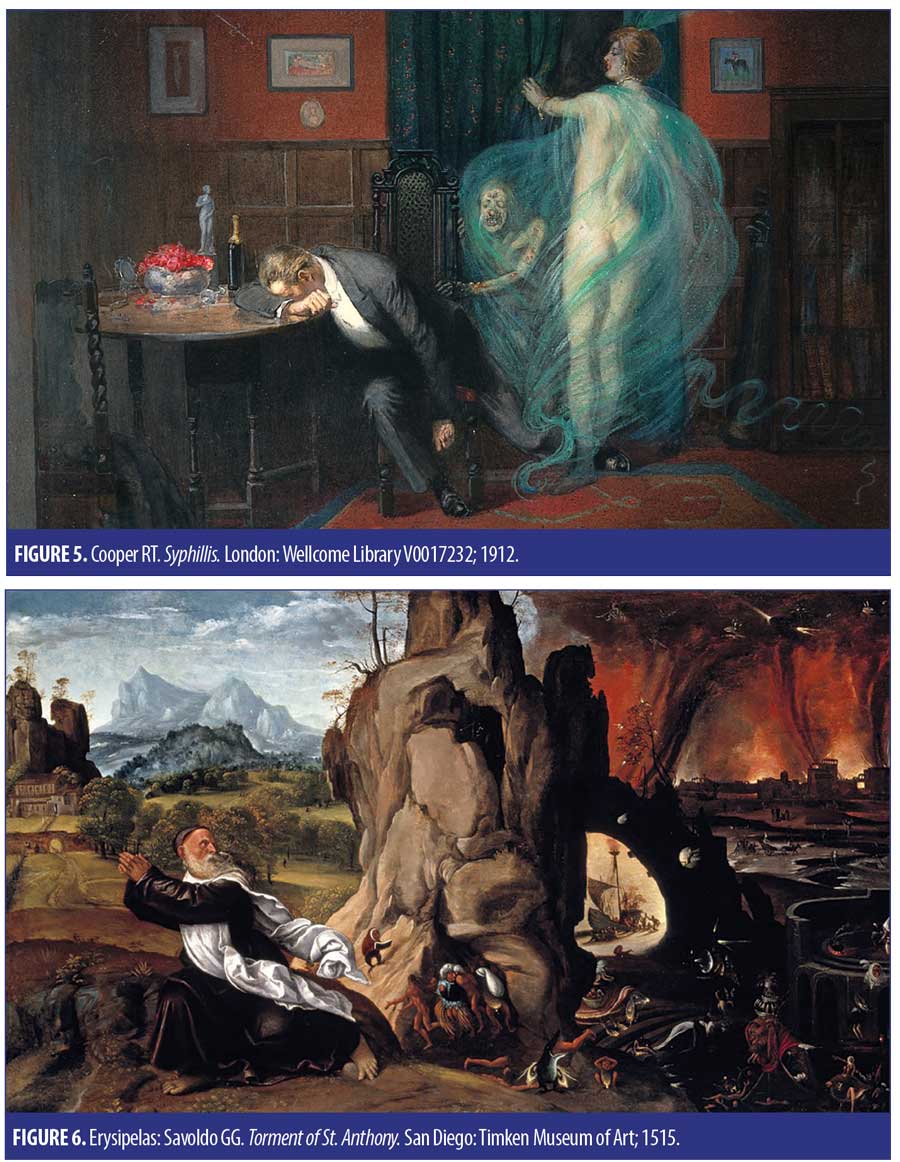

Edvard Munch’s The Inheritance (Figure 1) is meant to depict a “transfer of sin” between mother and child.1 The child appears to have an erythematous, bullous rash, which is consistent with congenital syphilis. Additional stigmata includes frontal bossing in the child. Congenital syphilis is also the subject of Rembrandt’s Portrait of Gerard de Lairesse (Figure 2), which hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the disease that would later kill Gerard de Lairesse has been posthumously diagnosed by the distinctive saddle nose and periorificial rhagades around the corners of the eyes and mouth.2 Portrait of Mr. J. Kay (Figure 3) illustrates classic “hutchinson teeth,” again indicative of congenital syphilis, while Head of a Young Man (Figure 4), a portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger, shows lesions across the face with some evidence of verrucous patches in skin folds that are also suggestive of syphilis. Syphilis (Figure 5) by Richard Cooper depicts the transmission and ultimate result of syphilis.

Apart from syphilis, another infectious disease represented in paintings is erysipelas, or “St. Anthony’s fire,” depicted in the Torment of St. Anthony (Figure 6) by Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo. Prior to the advent of hand-washing, skin infections, as well as infections of other bodily systems, were rampant.3 It was common to ask for divine intervention to help heal these.4 In the painting, the artist portrays St. Anthony running from hell, which might represent the fiery red plaques and fever associated with erysipelas.

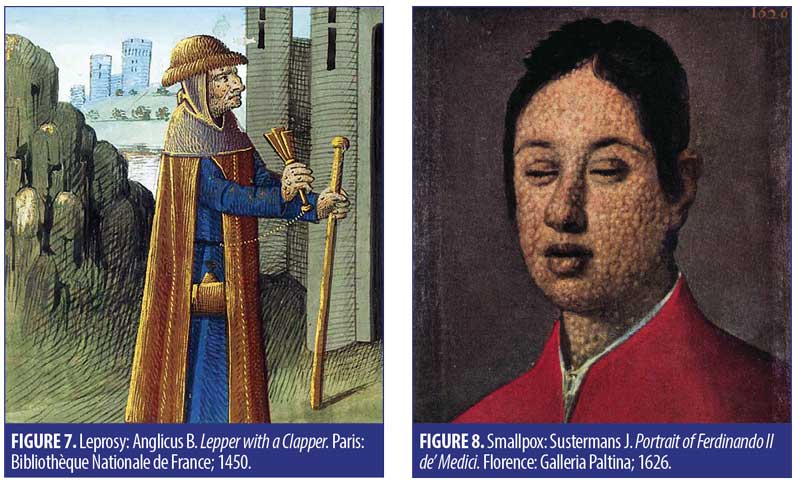

Leprosy is commonly depicted in art, as the cutaneous findings are quite striking. One example is Leper with a Clapper (Figure 7) by Bartholomeus Anglicus. The rattle was to alert others of his presence before arriving.5

The 1626 painting by Justus Sustermans, Portrait of Ferdinando II de’ Medici (Figure 8), might be a representation of smallpox. All the lesions appear to be in the same stage of development, which is suggestive of smallpox.

Neoplastic Conditions

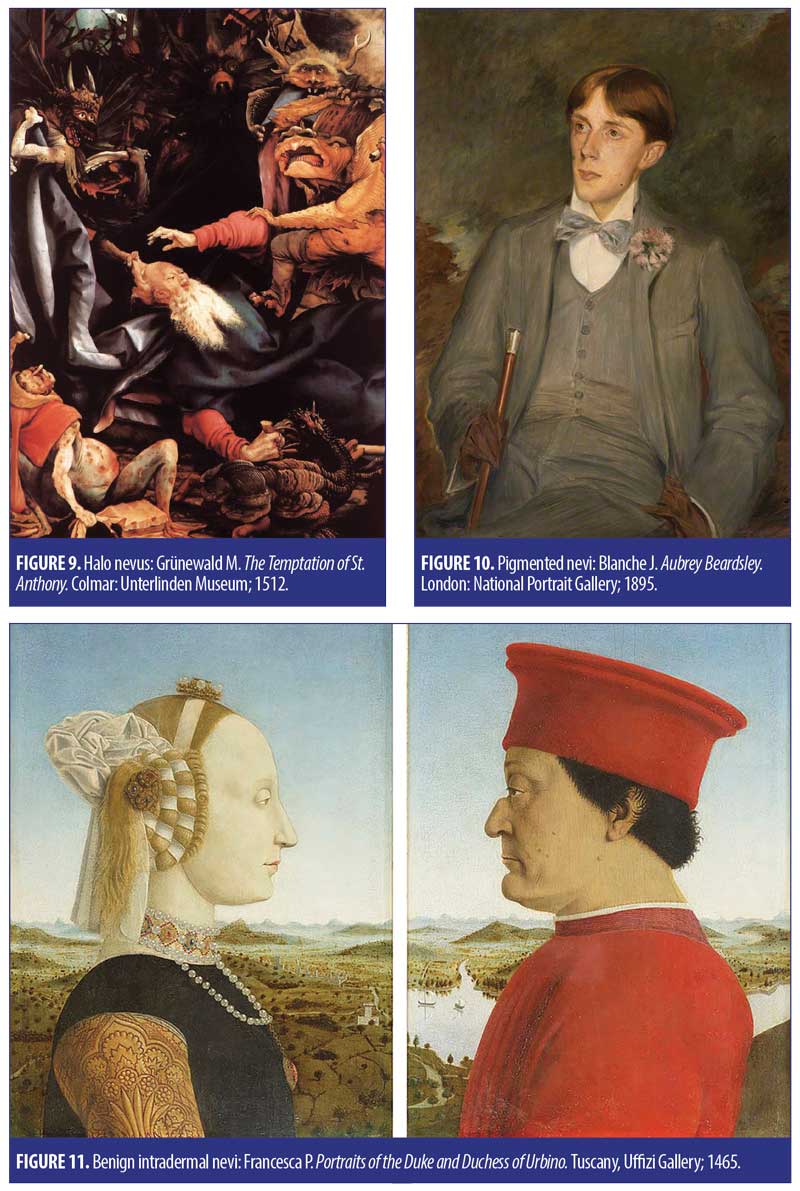

The Temptation of St. Anthony (Figure 9) by Matthias Grünewald shows a man with a distinctive halo nevus. Aubrey Beardsley (Figure 10) by Jacques-Emile Blanche is an 1895 oil canvas that shows two pigmented nevi, one on Jacques’s right cheek and another on the left jawline. Most melanocytic nevi appear within the first 30 years of life,6 in line with the age of the subject of the portrait.7 Piero della Francesca’s The Duke and Duchess of Urbino (Figure 11), one of the most famous paintings of the Italian Renaissance, portrays the Duke Federico da Montefeltro with what appear to be several benign intradermal nevi, identified by dome-shaped, skin-colored papules.

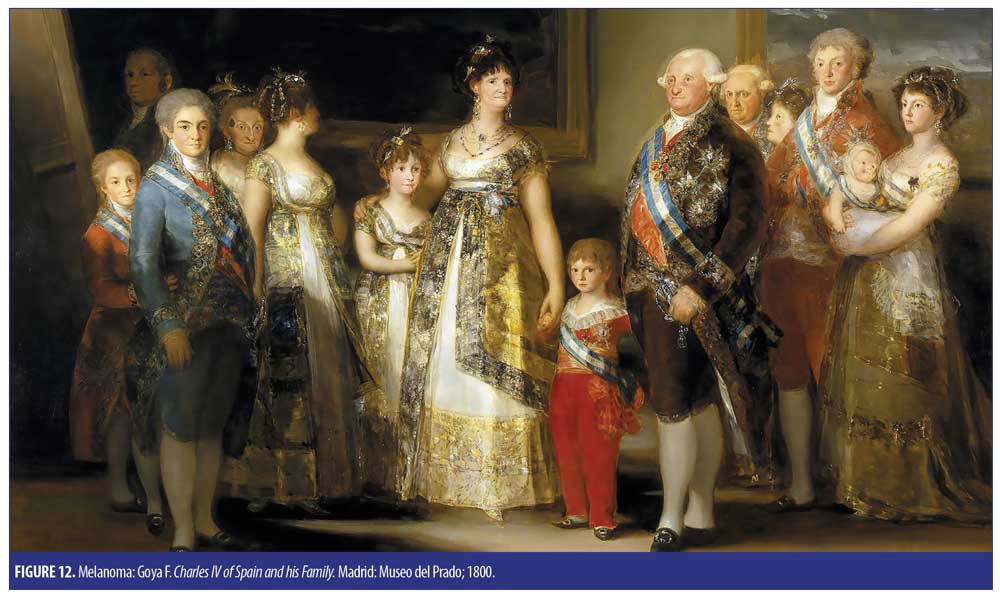

Francisco de Goya’s painting of Spanish King Charles IV and his family (Figure 12) portrays a woman with a concerning pigmented lesion, characterized by an irregular, black plaque with raised edges on her right temple. Goya was famous for portraying his subjects as accurately and honestly as possible8—many other artists would have covered an imperfection such as this. While it could represent a seborrheic keratosis, melanoma seems the most likely here. Suspiciously, the woman in the painting died only six months after this was painted.9

Genetic Dermatoses

Dermatologists are in a unique position to detect and diagnose the first signs of systemic disease that sometimes present in the neonatal period. Petrus Gonsalvus, perhaps most notable for being the real-life inspiration behind “Beauty and the Beast,”10 represents one such diagnostic case. Gonsalvus, often known as “Hair Man,” had Ambras syndrome (Figure 13). He regularly attended social events and became the subject of scholars and artists who frequently painted his family.10 His genetic disease was passed onto his daughter Tongnina, otherwise known as “Monkey Girl.”11

One of the subjects of a painting by Wilhelm Gottlieb Tilesius von Tilenau (Figure 14), a German explorer, is Edward Lambert. Lambert had a congenital syndrome known as ichthyosis hystrix. When explorers came across this man, they thought of him as a “porcupine man,” since his body was covered with hyperkeratotic spiny papules.12

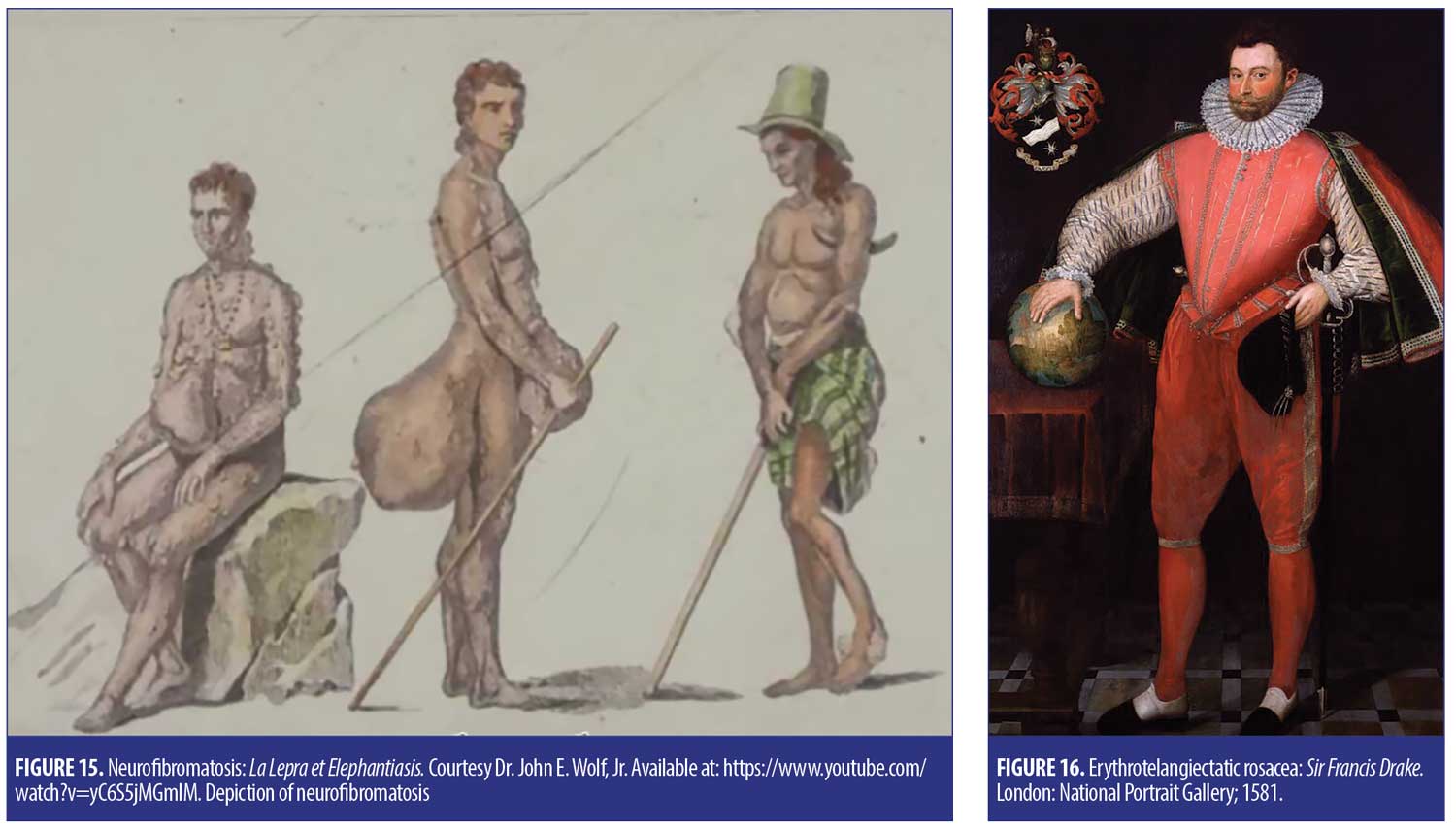

La Lepra et Elephantiasis is a misnomer; the condition depicted (Figure 15) is actually neurofibromatosis,1 not elephentiasis.

Rosacea/Acne

A portrait of Sir Francis Drake from 1580 (Figure 16) shows obvious erythema across his cheeks, consistent with erythrotelangiectatic rosacea. The Triumph of Bacchus (Figure 17), is a 1629 oil canvas that portrays a group of men celebrating, but one in particular (who is reaching for more alcohol) has a large, bumpy, and bulbous nose characteristic of rhinophyma. The painting is also called Los Borrachos, translating to “the drunks”; while the correlation between alcohol and rhinophyma has been well-propagated throughout literature (even Shakespeare himself tried to correlate the two), causation has yet to be verified.13 However, local vasodilation through alcohol can exaggerate this flushing.

Another 1490 Italian Renaissance painting, An Old Man and his Grandson (Figure 18) by Domenico Ghirlandaio, depicts rhinophyma. This painting is notable for its realism as well as defying the theory of physiognomy (physical defects are a representation of character14) by showing an old man as a loving grandfather despite his blemish. Many portraits from this era were modified to exclude deformities such as rhinophyma, as they were harder to sell.15 However, when these paintings were restored, the original conditions were made evident.16

The Tax Collectors (Figure 19), a 16th century painting by Marinus van Reymerswael, portrays two older gentlemen with pockmarks and ice pick scars, which represent the typical sequelae of untreated acne. Perhaps because these men were at an age where their skin had begun to lose collagen, these lesions appear more exaggerated.

Autoimmune Disorders

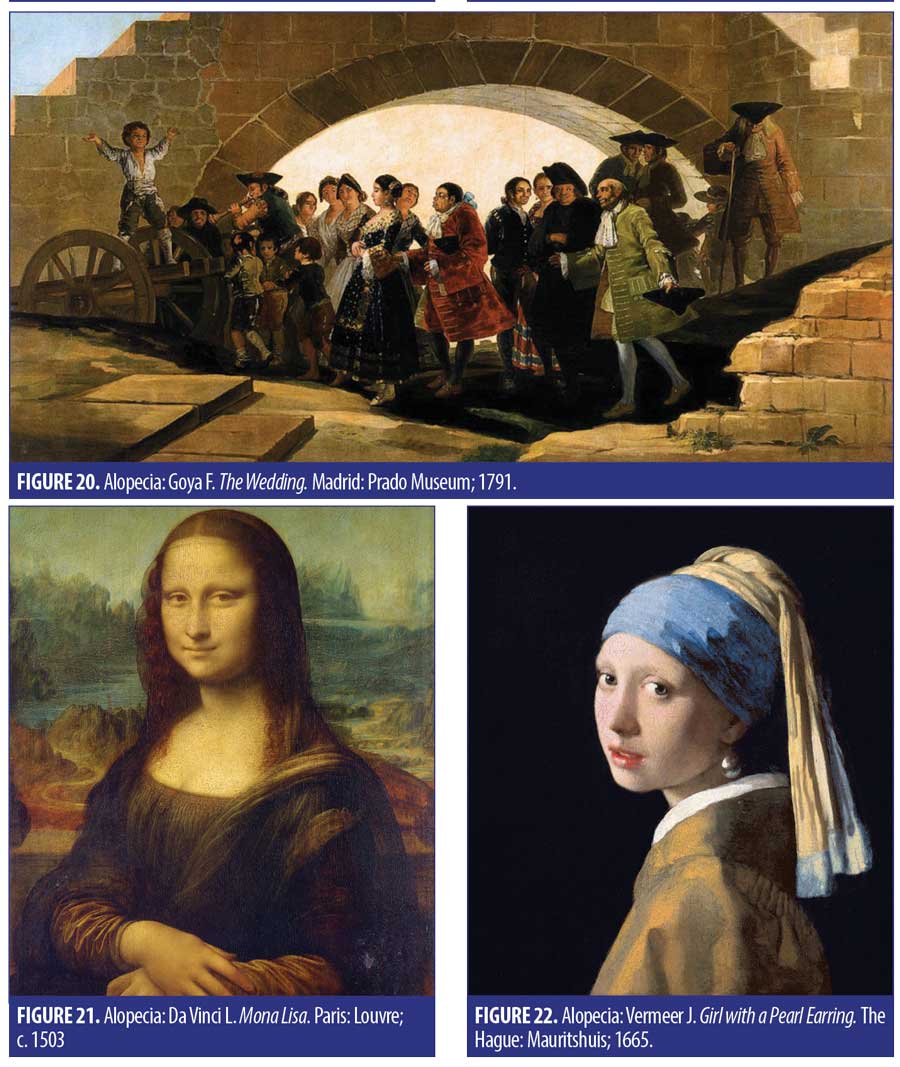

Goya’s painting of La Boda (Figure 20), or The Wedding portrays a young boy with what appears to be alopecia areata resulting in a well-defined, hairless patch on his head. While there is evidence that the Mona Lisa (Figure 21) was originally painted with eyebrows and lashes that have deteriorated through overcleaning,17 the painting as it is now portrays a woman who might have alopecia.18 Additionally, perhaps one of Vermeer’s most famous pieces, Girl with a Pearl Earring (Figure 22), also known as the “Mona Lisa of the North,”19 depicts what appears to be frontal fibrosing alopecia characterized by progressive hair loss near the forehead and thinning of her eyebrows.20

Miscellaneous/Other

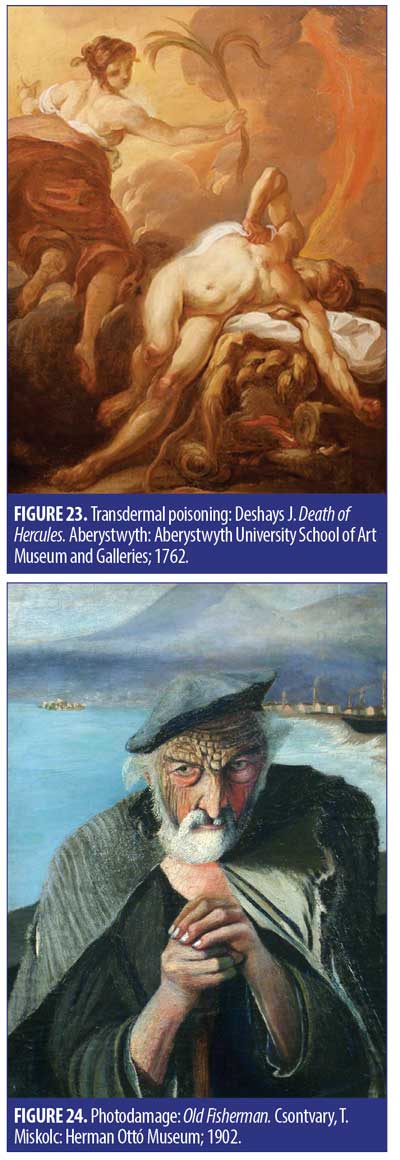

Deshays’ Death of Hercules (Figure 23) portrays a Greek mythological story21 that revolves around a dermatological cause of death. According to Greek mythology, a centaur-blood soaked cloak burned the skin of Hercules,21 and Deshays’ painting illustrates the death of Hercules by transdermal poisoning.

The Old Fisherman (Figure 24) is a 1902 oil painting that appears to depict photodamaged skin. An old fisherman would likely have a lifestyle prone to excessively sun-damaged skin, and his condition would be evidenced by wrinkling, roughness, and epidermal thickness.

Conclusion

The portraits presented in this article, whether purposefully or inadvertently, appear to depict various dermatological conditions, and lie on a spectrum from realistic and objective to stigmatized and subjective, with some artists even using their representations to attempt to overcome stigmas of skin disease. It is important that we dermatologists continue to reflect on how diseases of the skin are represented in our culture, with the understanding that these representations might reflect and affect how patients perceive their own disease. The representation of dermatological conditions through art, both objectively and subjectively throughout the centuries, demonstrates the highly aestehtic nature of our profession.

References

- Davis D, Jennings S. Scenes of Madness. London: Routledge; 1996.

- Johnson HA. Gerard de Lairesse: genius among the treponemes. J R Soc Med. 2004;97(6):301–303.

- Mathur P. Hand hygiene: Back to the basics of infection control. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134(5):611–620.

- Hardt MD. History of Infectious Disease Pandemics in Urban Societies. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books; 2015:81.

- Monica G. Lepers and Their Bells. New York Times website. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/23/opinion/lepers-and-their-bells.html. 22 Feb 2013. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- British Association of Dermatologists. Melanocytic Naevi (Pigmented Moles). Bad.org.uk. https://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=100&itemtype=document. Sept 2017. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- National Portrait Gallery. Aubrey Beardsley.https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw00427/Aubrey-Beardsley. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- Francisco de Goya Paintings, Prints, & Artwork. http://www.francisco-de-goya.com/. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- White LP. What the artist sees and paints. West J Med. 1995;163(1):84–85.

- Carolyn C. Petrus Gonsalvus: The Real-Life Inspiration Behind “Beauty and the Beast”. The Portalist. https://theportalist.com/petrus-gonsalvus-the-real-life-beauty-and-the-beast. 6 Sept 2016. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- Wiesner-Hanks M. The wild and hairy Gonzales family. Apparences. 2014; 5. http://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1283.

- Marmelzat WL. Story of the original “porcupine men”: Classical descriptions of ichthyosis hystrix. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1948;58(3):349–353.

- Augustynowicz A, Maranda EL, Zullo J, Cai L, Jimenez J. The bard’s blunder—debunking the myth around rhinophyma. JAMA Dermatology. 2016;152(4):379.

- Cadogan J, Ghirlandaio D. Domenico Ghirlandaio. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press; 2000:176.

- Rivett-Carnac M. Face value: portraiture and facial disfigurement. Art UK website. https://artuk.org/discover/stories/face-value-portraiture-and-facial-disfigurement. 27 Feb 2014. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- Thiébaut D, Depagniat M. Work: Old man with a young boy. The Louvre Museum website. https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/old-man-young-boy. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- Holt R. Solved: why Mona Lisa doesn’t have eyebrows. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/3668700/Solved-Why-Mona-Lisa-doesnt-have-eyebrows.html. 22 Oct 2007. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- Scailliérez C. Work: Mona Lisa—portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo. The Louvre Museum. https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/mona-lisa-portrait-lisa-gherardini-wife-francesco-del-giocondo.

- Cohen S. ‘Mona Lisa of the North’ Arrives in U.S. Wall Street Journal website. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324624404578257720138657446. 24 Jan 2013. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- Sooke A. Vermeer’s girl with a pearl earring: Who was she? The British Broadcasting Company (BBC). http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140701-who-was-the-mysterious-girl. 21 Oct 2014. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- Death of Hercules. Art UK. Artuk.org. https://www.artuk.org/discover/artworks/death-of-hercules-176520.