J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(9):13–18

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(9):13–18

by Ravi Jandhyala, MSc, MBBS, MRCS, MFPM, LLM, MBA

Dr. Jandhyala is with Medialis Ltd. in Banbury, United Kingdom.

Funding: No funding was provided for this study.

Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Background. Aesthetics remains a novel, poorly-regulated field of medicine.

Objectives. This study compared the scientific backgrounds of speakers at major conferences related to aesthetic medicine.

Methods. Records from conferences that took place in 2015 in aesthetics (Facial Aesthetic Conference and Exhibition [FACE]), plastic surgery (British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons [BAAPS]), and dermatology (British Association of Dermatologists [BAD]) were reviewed for professional backgrounds and publication histories of conference speakers.

Results. FACE 2015 was the largest conference and included “aesthetics doctors” among speakers from diverse professional backgrounds. Speakers at BAD 2015 and BAAPS 2015 were mostly dermatologists and plastic surgeons. Overall and when grouped by profession, speakers at FACE 2015 had fewer authorships and were less likely to have authored any peer-reviewed papers. Only 17 percent of speakers at FACE 2015 had contributed to relevant publications. Aesthetics doctors only averaged 0.37 authorships versus plastic surgeons (6.76) and dermatologists (13.92).

Conclusion. Most of the talks at FACE 2015 were presented by individuals with limited scientific backgrounds. The publication profiles of both FACE 2015 and aesthetic doctors were inconsistent with their fellow congresses and medical specialities. The results for aesthetic doctors might fall below the threshold deemed acceptable for doctors presenting themselves as experts in a branch of medicine, and might reflect a critical dearth of evidence-based practices in aesthetic medicine.

Keywords: Aesthetic medicine, conferences, evidence-based medicine, scientific background, speakers

Introduction

In the 16th century, an estimated 50 percent of medical practitioners in London were unlicensed barber-surgeons who offered speculative, overpriced treatments, of which safety and efficacy were unsupported by empirical evidence.1 Since then, medicine has evolved into a highly regulated, evidence-based practice that is divided into discrete specialist branches, each with their own requirements for professional registration. Collectively, these changes provide justifications for the risks and expenses associated with modern medicine.

In accordance with regulatory requirements, novel medical interventions are developed and repeatedly tested by scientists and physicians who are experts in the relevant field and who report on their work. Publication in indexed, peer-reviewed journals enables access by a wider audience and lends a degree of legitimacy to an investigator’s work.

Some journals pride themselves on limiting their acceptance rates to preserve their reputation and ensure only the highest quality research is associated with it. Another avenue for promoting research is submitting it for presentation at a meeting or congress of academic peers. In this setting, a live interaction between the presenter and the audience enables the opportunity to question the speaker and gain further insights into the work.

Aesthetics, or aesthetic medicine, is a fledgling branch of medicine yet to be recognized by the professional bodies that govern the practitioners within it. For example, the General Medical Council maintains specialist registers for plastic surgeons, dermatologists, and general practitioners but not for so-called “aesthetic doctors.” A similar situation exists in the General Dental Council and the Nursing and Midwifery Council. Consequently, aesthetic doctors leverage their primary or earlier qualifications to practice in the field.

Given the rapid proliferation of novel nonsurgical procedures being offered by aesthetic doctors (the value of the industry in the United Kingdom was estimated at $4.3 billion in 20152) and, based on the associated rise in the number of “experts,” it would follow that an equivalent volume and quality of evidence would be generated in order to 1) demonstrate their efficacy and 2) confirm the equivalence of aesthetic medicine to other recognized specialities to justify recognition in its own right.

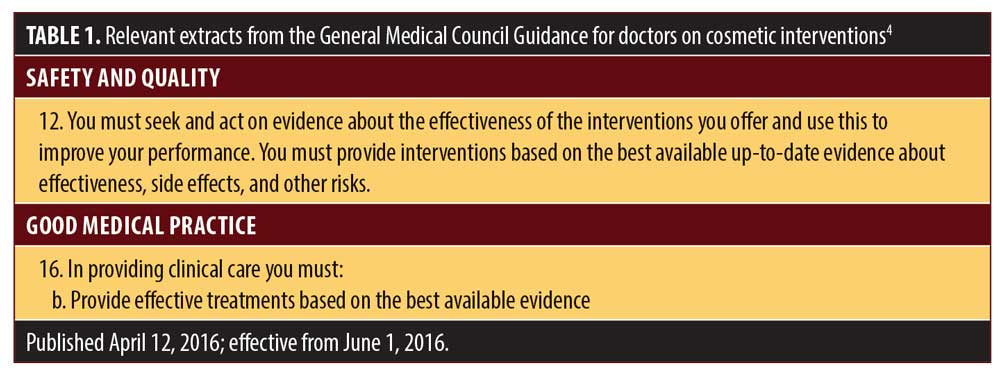

However, instead, a potential disparity between aesthetic medicine and other mainstream specialities has been suggested by the Keogh Report, which highlighted the risks associated with the practice of aesthetics, including both aesthetic medicine and surgery.3 This increased focus on aesthetic practice has prompted updated guidelines to be released by the General Medical Council, which has stressed the requirement of evidence-based practice for doctors offering cosmetic interventions (Table 1).4 Furthermore, two recent systematic reviews examining popular, nonsurgical aesthetic treatments have highlighted a lack of evidenced-based practice in cosmetic medicine. A review considering the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for facial rejuvenation failed to yield any studies meeting the inclusion criteria, indicating that treatments are being offered without evidence of safety or efficacy.5 Separately, another review into the use of dermal fillers for facial rejuvenation showed fewer than 10 percent of the dermal fillers available in the United Kingdom had any evidence supporting their efficacy or safety.6

Under these circumstances, the importance of proper regulation across all specialities with respect to the effectiveness and safety of their treatments, as well as practitioner training in and the quality of evidence underpinning these treatments has never been more important.

Methods

In order to assess a standard against which aesthetic medicine and its experts could be measured, two allied, recognized specialities were selected (plastic surgery and dermatology) and annual congresses for each were analyzed along with the publication count of their speakers in 2015.

A single main conference was identified for each of the following specialities: aesthetics (Facial Aesthetic Conference and Exhibition [FACE]); plastic surgery (British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons [BAAPS]); and dermatology (British Association of Dermatologists [BAD]).

The handbooks from each 2015 conference were analyzed for the titles and speakers at each talk. Handbooks contained the professional status of all speakers, which were categorized as plastic surgeon, dermatologist, aesthetics doctor, nonmedical professional, nurse, or scientist.

Presentations were also given by speakers from other medical professions, including clinical nutritionists, directors and product formulators, physiotherapists, medical aestheticians, clinical technologists, consultant vascular surgeons, laser protection advisors, cosmetic surgery councillors, chairs of trustees, trichologists, dental surgeons, aesthetic dentists, ophthalmologists, and experienced laser eye surgeons. These talks were excluded from this analysis because the numbers of speakers from these professions both individually and collectively were too low to warrant categories of their own.

Publication histories were assessed by searching each speaker’s name in PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/). The relevance of publications to presentations was determined subjectively by an individual assessor by converting the title of each talk into talk themes and then determining if that theme was relevant to the titles of each of the speaker’s publications. Duplicate presentations were not excluded from this analysis, so results would reflect the average talk at each conference. Because the data did not appear to be normally distributed, means and interquartile ranges are typically presented, although means are also included to differentiate between groups in which the median was equal to zero.

Results

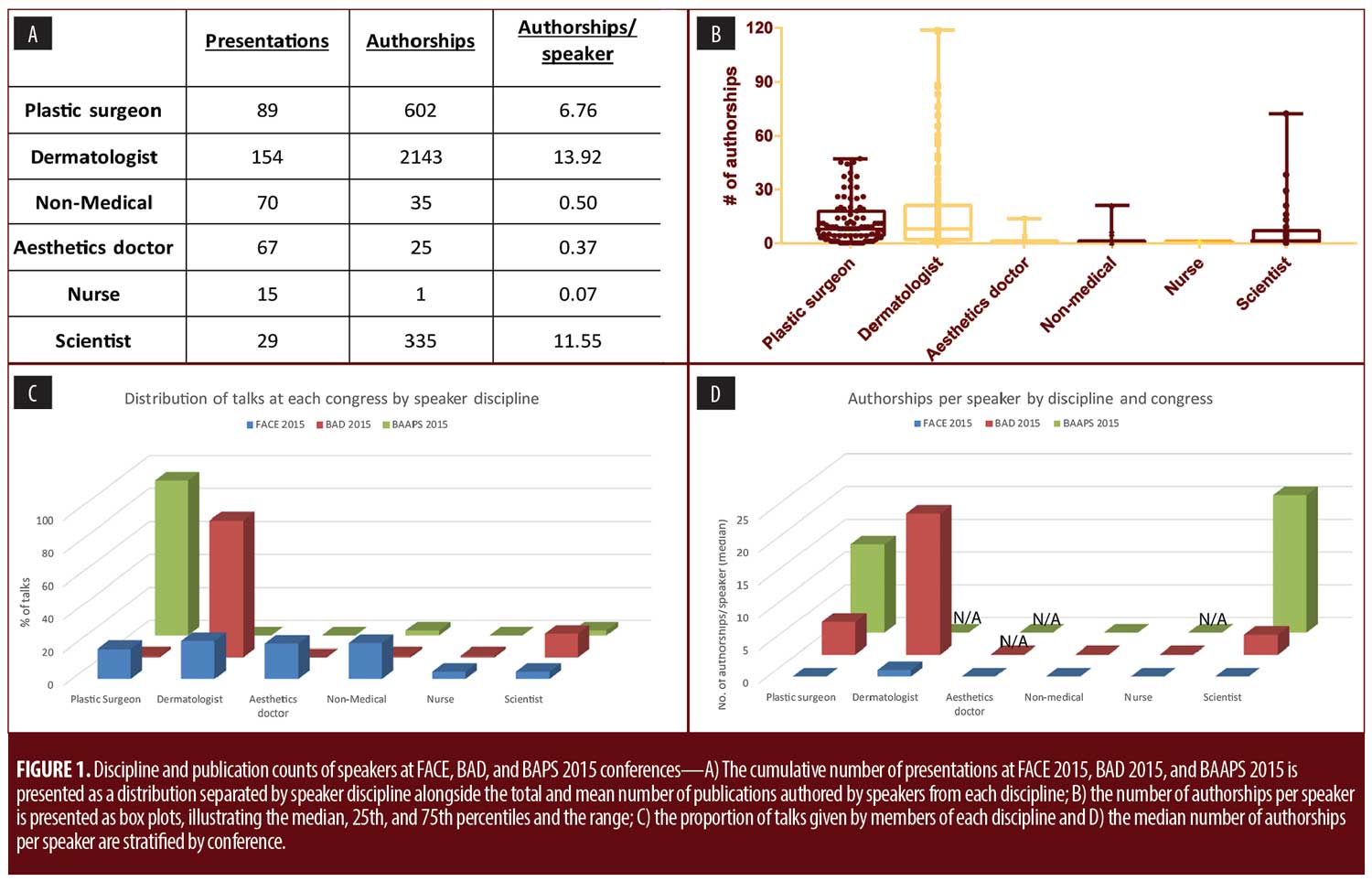

A total of 423 presentations from the FACE (292), BAD (99), and BAAPS (32) 2015 conferences were included in the present analysis. Since different professions are variously likely to contribute to academic publications, conference speakers were separated by professional background (i.e., plastic surgeon, dermatologist, aesthetics doctor, nonmedical, nurse, and scientist). Of these groups, only the dermatologists (13.9 authorships/speaker), scientists (11.6), and plastic surgeons (6.8) had contributed to an average of more than one peer-reviewed publication per person (Figure 1a) and had a median result of greater than zero (Figure 1a). The other groups had only contributed to an average of fewer than 0.5 papers per speaker, with aesthetics doctors having published far less than their fellow doctors.

A further separation of the results along conference lines revealed that the BAD (83% dermatologists) and BAAPS (94% plastic surgeons) conferences mostly selected speakers from a specific professional background, while the FACE conference was more generalized in their approach, accepting speakers from a wide range of professional backgrounds (Figure 1a). No more than 25 percent of speakers at FACE 2015 came from any one discipline (e.g., dermatologists), and other major groups included nonmedical (23%), aesthetic doctors (22%), and plastic surgeons (20%). While BAD 2015 featured only one speaker each from the plastic surgeon, nursing, and nonmedical backgrounds, BAAPS 2015 did not feature any speakers with nonmedical, aesthetic, or nursing backgrounds. Neither BAD 2015 nor BAAPS 2015 included presentations from aesthetic doctors.

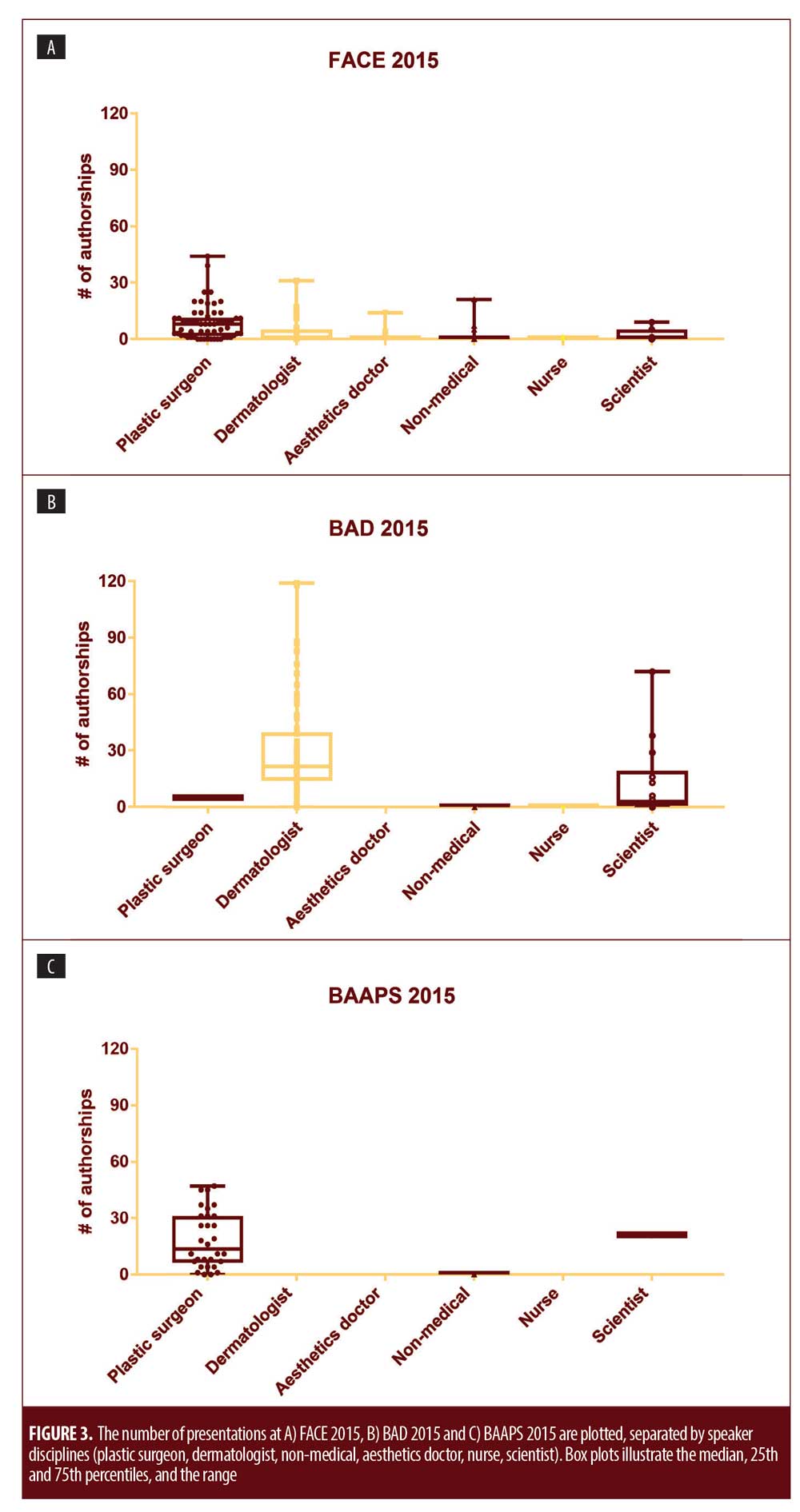

Separating the number of publications per speaker by profession and by conference revealed a clear trend: specifically, that people who presented at FACE 2015 had contributed to fewer papers, regardless of professional background (Figure 1d). Box plots of these data are presented in Supplementary Figure S1 for a more detailed depiction.

Although scientists spoke 14 times at BAD 2015 and at FACE 2015, the scientists speaking at BAD had contributed to a greater median number of peer-reviewed publications (3) than did the scientists speaking at FACE (0), and the Q3 result was considerably higher (15.25 vs. 4). Meanwhile, the only scientist who presented at BAAPS 2015 had contributed to 21 papers to date (Figure S1).

Likewise, the dermatologists who presented at FACE 2015 had contributed to far fewer publications (median of 1 authorship) than did the dermatologists who constituted the bulk of attendees at BAD 2015 (median of 21.5 authorships) (Figure 1d). Among plastic surgeons, the trend was similar (i.e., FACE median: zero authorships/person; BAD median: five authorships/person; BAAPS median: 13.5 authorships/person [Figure 1d]).

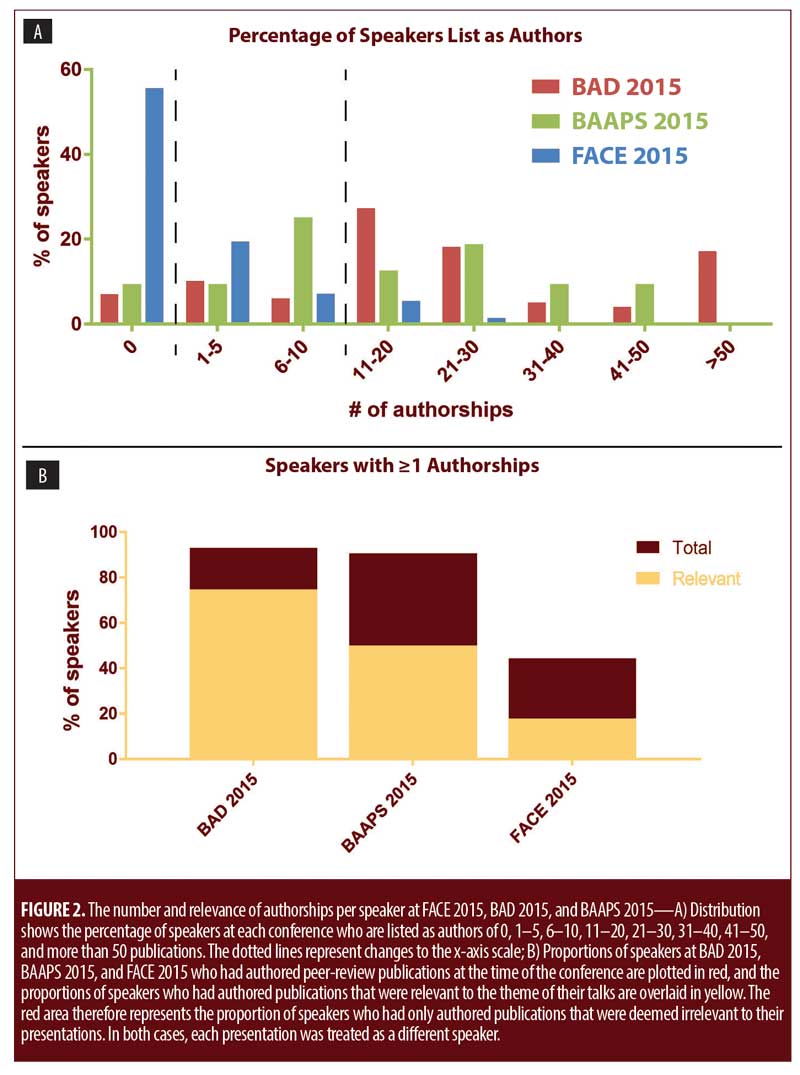

To reflect typical presentations at each conference, the publication records of speakers at each conference were then assessed without considering the professional backgrounds of the speakers (Figures 2 and 3).

Generally, speakers at BAD 2015 and speakers at BAAPS 2015 had been published considerably more compared with speakers at FACE 2015 (Figure 2a). FACE 2015 clearly had more speakers with fewer than five authorships, while a majority of speakers at the BAD and BAAPS conferences had more than 10 authorships, including roughly 20 percent of speakers who had greater than 30 publications, a threshold which none of the speakers at FACE successfully passed.

When the publications of speakers were assessed for relevance to their talks, FACE fell even further behind, with only 17 percent of speakers having authored at least one peer-reviewed publication that was deemed relevant to the subject of their presentations, in comparison with 75 percent of speakers at BAAPS and 52 percent of speakers at BAD (Figure 2b).

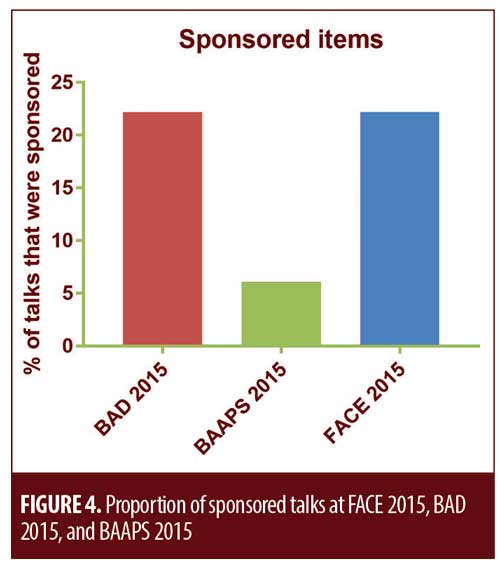

Commercial sponsorship might also affect the integrity of talks and was much more common at FACE 2015 (22%) and BAD 2015 (20%) than at BAAPS 2015 (6%) (Figure 4).

Discussion

It was found that speakers at FACE 2015 had contributed to fewer publications on average as compared with speakers at BAD 2015 and speakers at BAAPS 2015 (Figure 2a). Plastic surgeons, dermatologists, and scientists presenting at FACE also had fewer authorships than did their peers at either of the other two conferences (Figure 1d). Although aesthetics doctors delivered more than 20 percent of the talks at FACE 2015 (Figure 1c), they had only contributed to an average of 0.37 papers per person and had not presented at the other conferences. Furthermore, it was determined that 83 percent of the speakers at FACE had not contributed to any peer-reviewed literature that was relevant to the subject of their presentation. These results are concerning and might constitute a sign of the dearth of evidence-based practice in the field of aesthetic medicine or, more worryingly, indicate its cause.

The vast majority of individuals seeking aesthetic treatments are not suffering from any disease, disorder, or dysfunction and can therefore be considered to be healthy individuals. A medical intervention that has no published evidence of safety and efficacy can be called an “experimental treatment.” While use of experimental medical interventions can be justified in the management of a medical condition with the objective of restoring health,7 their use in improving appearance in healthy individuals can be less easily defended. Any medical treatment carries a level of risk, and the balance of this risk against the intended benefit can only be informed with the availability of good-quality evidence. Medical negligence case law also supports the practice of assessing the benefit and risk of any proposed medical intervention.8

In the currently unregulated field of aesthetic medicine, it is even more important that the treatments being offered have been through the appropriate clinical testing. The use of improperly tested medical interventions breeches the central tenets of medical ethics, including nonmaleficence (primum non nochere, or “first do no harm”), when the safety of a treatment has not been adequately tested; beneficence, when insufficient evidence supports the efficacy of a treatment; and respect for autonomy, when insufficient information is available for patients to make an informed decision.

Limitations. A central tenant of science is skepticism, so the limitations of this preliminary report must be noted. There are many scientific databases, and repeating the literature searches in multiple databases would add confidence to the number of publications attributed to each speaker. In the interests of simplicity, the searches were only performed on PubMed, which is publicly available and, as of July 2017, contained more than 27 million citations. Another considerable limitation is that the data presented above were only collected from one conference year. A greater sample size (e.g., obtained through involving more conferences) would be required to make statistically significant comparisons between conferences or between fields. Yet, the collection and analysis of the current dataset was very time- and labor-intensive. Although the expansion of this dataset could be facilitated by automation, conferences are typically organized by and for specific groups of people and would be expected to consistently attract and accept a certain group of speakers. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the conference attendance data from one year are likely to be representative of the conference in general.

Due to practical constraints, the identified presentations and publications were not assessed for their quality. Presentations might have included observational studies where a therapeutic intervention was not used and publications might have included the donation of patient data to a larger study, without the author fully understanding the basis of the study or contributing to the preparation of the final document. Other bibliometric parameters that could be used to assess the scientific contribution of presenters in more detail include impact factor, eigenfactor, and h-index (which accounts for both the number and the impact of publications). For this report, people with little or no publication record were of more interest than discerning between highly published academics, so the number of authorships was chosen for its simplicity and sensitivity in this area. The assessment of relevance was also highly subjective, and there is a risk of bias in having a single assessor view abstracts and categories. This approach should be refined for further use, and preferably be automated. Keyword searches could be used, but the appropriate selection of keywords would be crucial. However, in most cases, the relationship between presentation and publication was readily apparent, and it is difficult to imagine an approach to measuring relevance that is not subjective or biased.

It is accepted that individuals without publications in peer-reviewed, indexed journals should still be permitted to present at conferences. Indeed, student presentations play an important role in many conferences, and appropriate scientific training and background reading can somewhat compensate for a lack of peer-reviewed publications.

It can be argued that publication count alone is not an adequate measure of the inherent quality or the importance of an individual in most professions. While the job of a scientist could be described as to “generate as many high-quality publications as possible,” the job of a plastic surgeon is ultimately to perform surgery, and any contributions to science by such an individual would thus be made in addition to their main work as a matter of personal interest—unless they perform an experimental treatment, when the onus is upon them to publish their results in order to assess its efficacy and safety. Although a publication record is not the measure of a good doctor, it is the measure of a good (and experienced) scientist and is to some extent a measure of the credibility of a speaker presenting at a scientific conference. When 40 percent of speakers at an aesthetics conference are unpublished, and when presenting aesthetics doctors have published considerably less often than their fellow medical doctors have, it raises concerns about the content of the conference and about the scientific basis of the broader field.

Conclusions

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the data presented highlight a failing in the field of aesthetic medicine. In order for aesthetic medicine to be recognized alongside other branches of medicine, it must be held to the same standards as those other branches, including with respect to the profile of its experts. It is clear from this work that the profile of speakers at the aesthetics congress is inconsistent with those of recognized, allied branches of medicine, and, therefore, speaker and subject matter quality is unlikely to be equivalent. The inferior publication profile of aesthetic doctors reported here represents a risk to achieving legitimacy for their speciality. A lack of scientific investigation into the efficacy and particularly into the safety of many practices will leave aesthetic medicine more aligned with 16th century practices than with modern medicine. It is strongly recommended that more aesthetics doctors undergo scientific training and publish their findings so as to justify their interventions and thereby support best practice, with the goal of achieving recognition of the field by regulatory authorities.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Ms. Jan Moore for reviewing the conference abstracts.

References

- Pelling M, Webster C. Medical Practitioners. In: Webster C, editor. Health, Medicine and Mortality in the Sixteenth Century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1979. p. 165–235.

- Department of Health. Review of the Regulation of Cosmetic Interventions. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/192028/Review_of_the_Regulation_of_Cosmetic_Interventions.pdf. April 2013. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- Keogh B. National Health Service. Review into the quality of care and treatment provided by 14 hospital trusts in England: overview report. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/bruce-keogh-review/Documents/outcomes/keogh-review-final-report.pdf. 16 Jul 2013. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- General Medical Council. Guidance for doctors who offer cosmetic interventions. Available at: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/28687.asp2016. 12 April 2016. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- Jandhyala R. Dermal fillers for facial rejuvenation: a review of clinical evidence. J Aesth Med. 2015;1(1):6–13.

- Jandhyala R. Platelet-rich plasma for facial rejuvenation, a system review. J Aesth Med. 2016;2(1):1–3.

- European Comission. Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the community code relating to medicinal products for human use OJ L 311. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-1/dir_2001_83_cons2009/2001_83_cons2009_en.pdf. 6 Nov 2001. Accessed 12 Sept 2018.

- Bolitho (Deceased) v. City and Hackney Health Authority [1997] 3 W.L.R. 1151.