J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(8):44–48.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(8):44–48.

by Khaled Gharib, MD; Fawzia Farag Mostafa, MD; and Soheir Ghonemy, MD

All authors are with the Department of Dermatology, Venerology and Andrology, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Melasma is a chronic acquired focal pigment disorder showing symmetrical hyperpigmentation or hypermelanosis of photoexposed areas on the face. Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a treatment for melasma. The regression of melasma after platelet-rich-plasma (PRP) treatment is an interesting finding.

Objective. We investigated the effect of microneedling followed by PRP versus microneedling followed by tranexamic acid in the treatment of patients with melasma.

Methods. The study included 26 patients with melasma divided into two groups of 13 patients each. Group 1 was treated with microneedling and PRP, and Group 2 was treated with microneedling and tranexamic acid.

Results. The response to treatment was assessed using the Melasma Area and Severity Index scoring system before and after treatment. At the start of the study and at the first session, there were no statistically significant differences (p>0.05). At the second and third treatment sessions, there were statistically significant differences (p<0.05). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding side effects of pain, erythema and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Conclusion. Microneedling with PRP offers better results than microneedling with TXA in treating melasma.

Keywords: Melasma, tranexamic acid, platelet-rich-plasma, microneedling

Melasma is a chronic acquired focal pigment disorder showing symmetrical hyperpigmentation or hypermelanosis of photoexposed areas on the face. It is characterized by light to dark brown patches with indistinct borders on both cheeks.1

Different treatment modalities have been used as topical depigmenting agents for melasma, including chemical peels, dermabrasion, and laser therapies, with varying and often unsatisfactory outcomes. Clinical trials using localized intradermal microinjections of tranexamic acid (TXA) and transepidermal delivery of TXA using microneedling in the treatment of melasma are promising.2

Skin microneedling is a simple and effective procedure. It is based on the natural ability of the skin’s self-repair mechanism by encountering injuries that triggers a cascade of growth factors and neutrophil production, boosting collagen and elastin products, which leads to skin tightening.3

Treatment with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is performed via the autologous injection of high concentrations of platelets in a small volume of plasma. The most important contents of platelets are contained in the alpha-granules and include more than 30 bioactive substances, such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1 and -beta2, epidermal growth factor, and mitogenic growth factors including platelet-derived angiogenesis factor and fibrinogen.4

This study sought to investigate the effect of microneedling followed by PRP versus microneedling followed by TXA in the treatment of patients with melasma.

Methods

This single-center clinical trial included 26 patients split into two groups of 13. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients participating in this study after approval from the ethical committee and institutional review board of the Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University Hospital, was obtained.

Study inclusion criteria were as follows: male or female patients of any age with melasma. Study exclusion criteria were pregnancy or lactation, active cutaneous infection, any concurrent endocrine disorder, use of hormone replacement therapy, oral contraceptives, or anticonvulsive therapy, history of any other depigmenting treatment in the past four months, and history of laser or intense pulsed light therapy in the previous six months.

All patients were subjected to the following procedures: full history-taking and general examination, detailed dermatological examination, examination of melasma lesions to determine outlines, and photographs taken before and after sessions to evaluate the results.

Treatment. Study participants were divided into two groups; Group 1 comprised 13 patients treated with microneedling with a needle depth of 1.5mm preceding topical application of PRP, while Group 2 comprised 13 patients treated with microneedling with a needle depth of 1.5mm followed by TXA. In both groups, topically anesthetic cream was applied to the face 20 minutes before treatment. Woods light analysis to determine the type of melasma (i.e., epidermal, dermal or mixed) was performed for all patients.

For PRP preparation, 10mL of autologous whole blood was collected into tubes containing acid citrate dextrose and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 10 minutes in order to retain PRP at the top of the test tube. Then, the PRP was centrifuged at 3,700 rpm for 10 minutes at a room temperature of 22°C to obtain a platelet count of 4.5 times higher than the baseline (i.e., 8–9 lakhs/uL). Platelet-poor plasma was partly used to resuspend the platelets. Calcium gluconate was added as an activator at a ratio of 1:9 (i.e., 1mL of calcium gluconate in 9mL of PRP).

TXA is available as a 5-mL ampoule containing 500mg of the active ingredient. A 30-gauge, 0.5-mL insulin syringe with 4mg/mL of TXA was prepared under sterile conditions, then topically applied.

Results

Group 1 included 13 female patients aged 35.46±5.09 years (range: 26–47 years) with skin phototype III or IV. The duration of melasma ranged from 1 to 10 years (mean: 4.00±2.88 years). According to Wood’s light examination, the type of melasma in patients was as follows: eight patients (61.54%) had the epidermal type and five patients (38.46%) had the mixed type. Four patients (30.77%) had a family history of melasma.

Group 2 included 13 female patients aged 35.92±5.72 years (range: 29–50 years) with skin phototype III or IV. The duration of melasma ranged from 1 to 10 years (mean: 5.04±3.16 years). According to Wood’s light examination, the type of melasma in patients was as follows: six patients (46.15%) had the epidermal type, two patients (15.38%) had the dermal type, and five patients (38.46%) had the mixed type. Two patients (15.38%) had a family history of melasma.

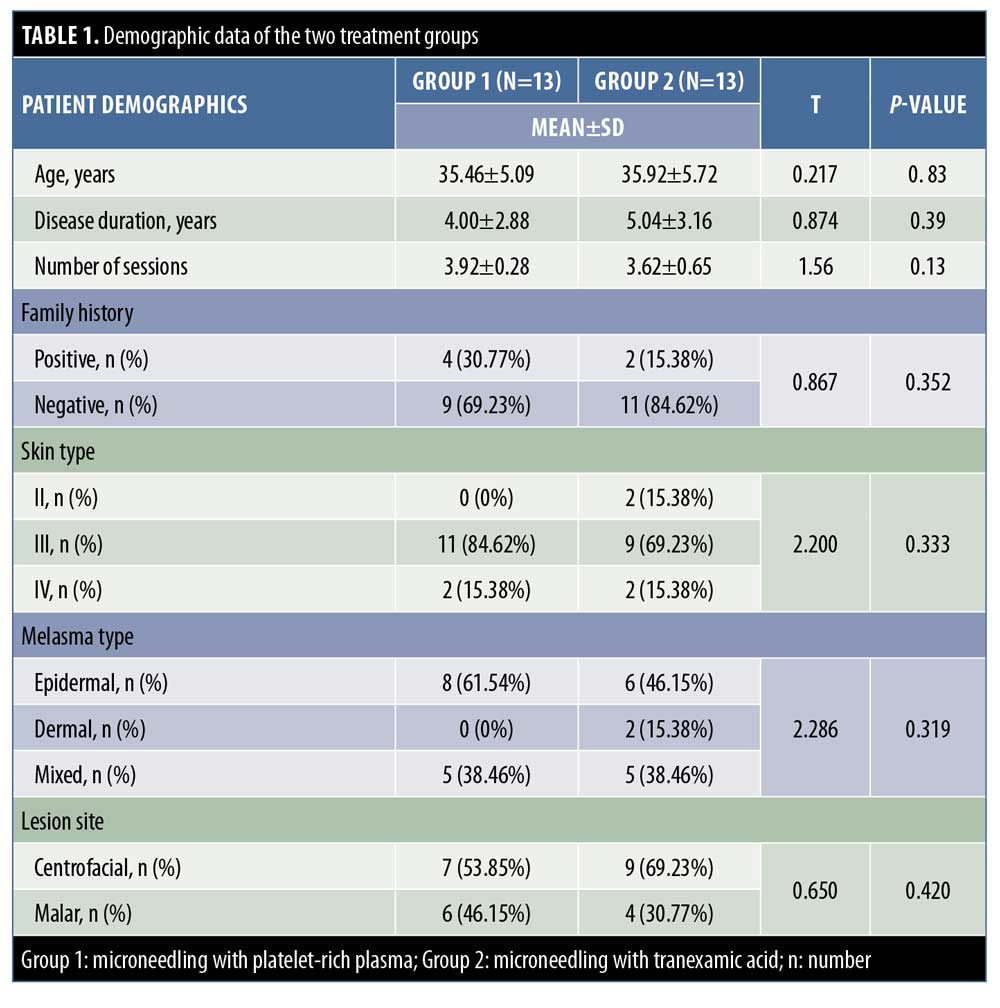

The demographic data of the two groups were properly matched regarding age, duration of disease, and number of sessions. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (Table 1). There were also no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding some disease-related characteristics, such as family history, skin type, melasma type, and site of lesions.

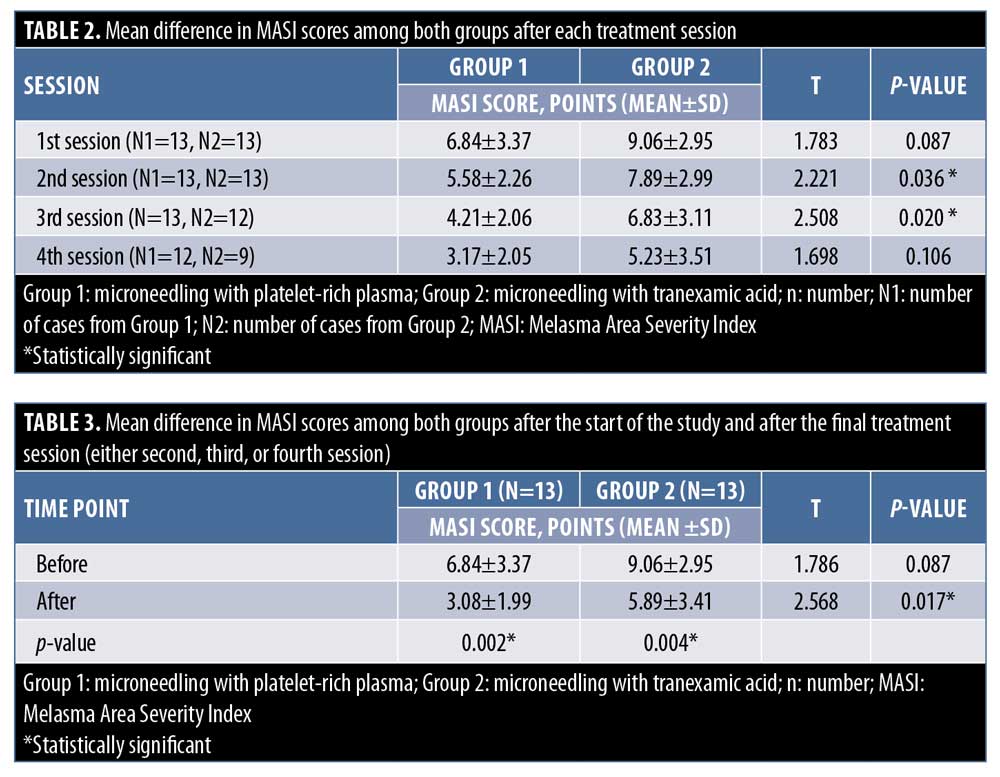

Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) scores. MASI scores before PRP with microneedling and after the second, third, and fourth sessions were recorded, and statistically significant differences between before and after the sessions were apparent (p<0.05). The mean MASI score after treatment decreased from 6.48±3.37 at the first session to 5.58±2.26 at the second session, 4.21±2.06 at the third session, and 3.17±2.05 at the fourth session.

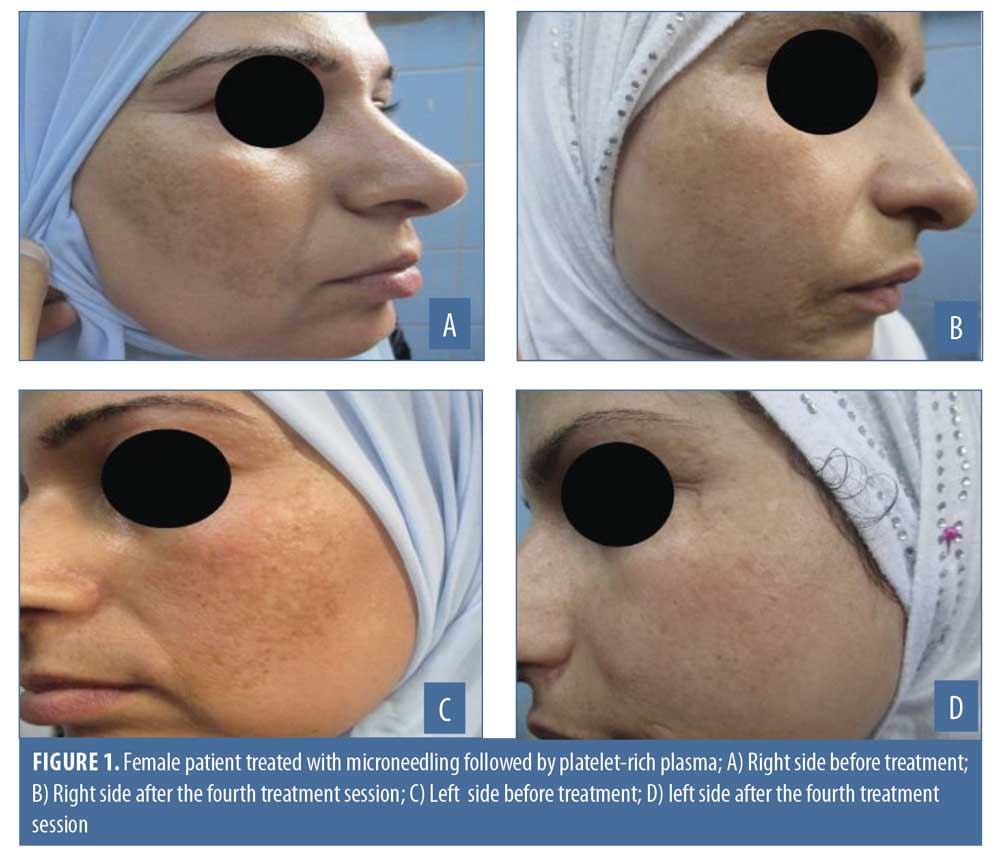

The response to treatment was assessed using the MASI scoring system before and after treatment (Table 2). At the start of the study, there were no statistically significant differences (p>0.05). At the second and third sessions, there were statistically significant differences (p<0.05). At the fourth session, there were no statistically significant differences (p>0.05) (Figures 1–3).

Before the treatment sessions, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (p>0.05). After the sessions, there were statistically significant differences between the two groups (p<0.05). There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups at the completion of the fourth session (P<0.017) (Table 3).

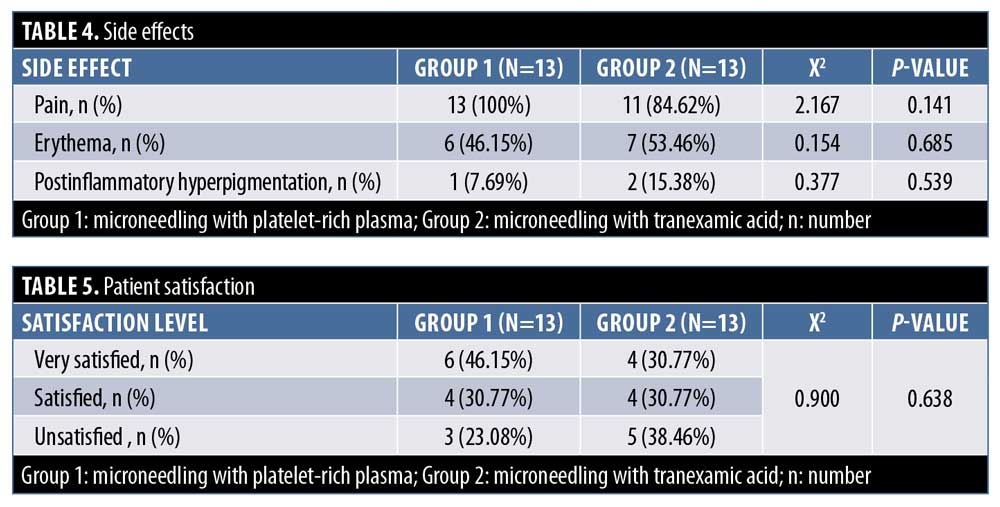

Side effects. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding side effects, including pain, erythema, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Table 4).

Patient self-assessments. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups. The patient self-assessment of melasma improvement was evaluated and six patients (46.15%) were very satisfied, four patients (30.77%) were satisfied, and three patients (23.08%) were unsatisfied in Group 1, while four patients (30.77) were very satisfied, four patients (30.77) were satisfied, and five patients were unsatisfied in Group 2 (Table 5).

Discussion

Melasma is a common acquired hypermelanosis that occurs exclusively on sun-exposed areas, mostly on the face and occasionally on the neck and forearms. Melasma is a dermatological disease easily diagnosed by clinical examination that is typically chronic with frequent recurrences with many unknown pathophysiological aspects.5–7

PRP is gaining attention in aesthetic medicine. PRP is blood plasma that has been enriched with platelets. As a concentrated source of autologous platelets, PRP contains several different growth factors and other cytokines that can stimulate various effects in soft tissue. PRP could be a promising treatment with less side effects and rebound hyperpigmentation relative to other melasma treatments.8–10

The addition of TXA for the treatment of melasma is a novel concept. Previously used as an antifibrinolytic agent, TXA is found to inhibit plasminogen-keratinocyte interaction by decreasing the tyrosinase activity, causing decreased melanin synthesis from the melanocytes. Very few clinical trials have been conducted to date regarding the efficacy of TXA (oral, topical, or intralesional) for the treatment of melasma.11–14

The present study evaluated two groups of patients, one exploring the effect of microneedling with PRP and the other considering the effect of microneedling with TXA in melasma cases.

In our study, there were statistically insignificant differences between both groups regarding age, disease duration, and number of sessions. Also, differences in family history, skin type, melasma type, and site of lesions were statistically insignificant between the two groups. Two patients in Group 2 had dermal-type melasma. We found that, in Group 1, four patients had a family history, while two patients in Group 2 had a family history.

The present study revealed that the severity of melasma was reduced after treatment with microneedling plus PRP in many Group 1 patients. The difference in MASI score was statistically significant (p<0.002). The mean MASI score after treatment decreased from 6.48±3.37 at the first session to 5.58±2.26 at the second session, 4.21±2.06 at the third session, and 3.17±2.05 at the fourth session, respectively, revealing a 50-percent improvement from baseline to the end of all sessions. Microneedling with PRP could be an adjuvant therapy for melasma.

This study was different from that of Mutlu Çayirli et al,15 who reported that the effects of PRP injection at the end of the treatment led to a more than 80-percent reduction in epidermal hyperpigmentation.15 Meanwhile, Yew et al16 reported a reduction in mean MASI score in two cases (33.5% and 20%) after the administration of intradermal PRP with QS-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet laser application monthly for two sessions and topical alpha-arbutin applied every day. These differing results might be due to the smaller number of patients and different methods of treatment.

Arada et al17 studied 10 female patients with mixed-type melasma, where PRP was intradermally injected into one side of the face randomly (0.1/cm2) and normal saline was injected into the other side as a control group. These authors reported that MASI scores were reduced from 2 to 6 weeks (from 5 to 3.36), with statistically significant results. Also, these discordant results might be due to the different numbers of patients and methods of application.17

In our study, in Group 2, the severity of melasma was reduced after treatment with microneedling plus TXA. The difference in MASI score in this study between before and after treatment showed statistical significance (p<0.004). The mean MASI score after treatment decreased from 9.06±2.95 at the first session to 7.89±2.99 at the second session, 6.83±3.11 points at the third session, and 5.23±3.51 points at the fourth session, which revealed a 42-percent improvement from baseline to the end of all sessions.

Our study was similar to that of Budamakuntla et al,18 who compared TXA microinjection and TXA with microneedling in patients with melasma. The mean MASI score in the microneedling group at baseline was 9.11±4.09, while that at the end of the third visit during follow-up was 5.06±2.14, indicating a 44.41-percent improvement (p<0.001).18

Kim et al19,20 studied the effectiveness and safety of TXA alone or as an adjuvant in patients with melasma and reported a decrease by 1.60 points in MASI score after treatment with TXA. The improvement was significant between baseline and Week 4, and between Weeks 4 and 8. There was also improvement at the final follow-up timepoint (Week 12). The addition of TXA to routine treatment modalities resulted in a further decrease by 0.94 points in MASI score. Side effects were minor, with a few cases reporting hypomenorrhea, mild abdominal discomfort, and transient skin irritation. These authors supported the use of TXA as a treatment modality for patients with melasma.21

In another study by Atefi et al22 comparing 5% TXA cream and 2% hydroquinone (HQ) cream in two groups of people, significant improvements in MASI score in both groups, but no significant difference between the groups was apparent. A higher level of patient satisfaction was seen in the TXA group (33.3% vs. 6.7% in the HQ group). The HQ group also showed a greater incidence of adverse effects, such as skin irritation and erythema (10% vs. no major side effects in the TXA group).22

In our study, the mean difference in MASI score in both groups revealed that there was a statistically significant difference between both groups (p<0.017). Patients in Group 1 experienced a greater improvement. This means that the effect of microneedling with PRP is more effective than that of microneedling with TXA. This may be attributed to the that PRP contains alpha-granules, which have bioactive molecules with an important role in aspects of tissue healing and local regeneration, such as proliferation, migration, and cell differentiation and angiogenesis.23 No statistically significant differences in patient satisfaction or complications in both groups were recorded in our study.

To our knowledge, no previous studies comparing microneedling application followed by PRP in melasma and microneedling application followed by TXA in melasma exist.

Conclusion

Based on our results, microneedling with PRP offers better outcomes than microneedling with TXA in melasma cases. Further studies with more patients are necessary to confirm the efficacy of microneedling application with PRP and TXA, with longer follow-up periods to determine the recurrence rate of the disease.

References

- Lee MC, Chang CS, Huang YL, et al. Treatment of melasma with mixed parameters of 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser toning and an enhanced effect of ultrasonic application of vitamin C: a split-face study. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30:159–163.

- Budamakuntla L, Loganathan E, Suresh DH, et al. A randomised, open-label, comparative study of tranexamic acid microinjections and tranexamic acid with microneedling in patients with melasma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:139–143.

- Tantari SHW, Murlistyarini S. Combination treatment of skin needling, platelet-rich plasma and glycolic acid 70% chemical peeling for atrophic acne scars in Fitzpatrick’s skin type IV–VI. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2016;7:364.

- Kim DS, Park SH, Park KC. Transforming growth factor-beta1 decreases melanin synthesis via delayed extracellular signal- regulated kinase activation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36: 1482–1491.

- Bohara R, Bhamre N, Kshersagar J, et al. Platelet rich plasma: a potential treatment option in hyper pigmentation of skin. Clin Surg. 2018;3:1938.

- Hexsel D, Lacerda DA, Cavalcante AS, et al. Epidemiology of melasma in Brazilian patients: a multicenter study. Int J Dermatol. 2013;53:440–444.

- Tamega AA, Miot LD, Bonfietti C, et al. Clinical patterns and epidemiological characteristics of facial melasma in Brazilian women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(2):151–156.

- Langer C, Mahajan V. Platelet-rich plasma in dermatology. JK Science. 2014;16(4):147–150.

- Hofny ERM , Abdel-Motaleb AA , Ghazally A et al. Platelet-rich plasma is a useful therapeutic option in melasma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30(4):396–401.

- Kim DS , Park SH, Park KC. Transforming growth factor-beta1 decreases melanin synthesis via delayed extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(8): 1482–1491.

- Karn D, KC S, Amatya A, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2012;10(40):40–43.

- (13) Janney MS, Subramaniyan R , Dabas R. et al. A randomized controlled study comparing the efficacy of topical 5% tranexamic acid solution versus 3% hydroquinone cream in melasma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2019;12(1):63–67.

- Lei Zhang, Wei-Qiang Tan, Qing-Qing Fang, et al. Tranexamic acid for adults with melasma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1683414.

- Bala HR, Lee S, Wong C, et al. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(6):814–825.

- Mutlu Çayirli, Ercan Çaliskan, Gürol Açikgöz, et al. Regression of melasma with platelet-rich plasma treatment. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:401.

- Yew CH, Ramasamy TS and Amini F. Response to intradermal autologous platelet rich plasma injection in refractory dermal melasma: report of two cases. Journal of Health and Translational Medicine. 2015;18(2):1–6.

- Arada D, Natthanej L, Sompong D, et al. The potential role of platelet-rich plasma in melasma treatment. Thai Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2017;41:233–236.

- Budamakuntla L, Loganathan E, Suresh DH, et al. A randomised, open-label, comparative study of tranexamic acid microinjections and tranexamic acid with microneedling in patients with melasma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6(3):139–143.

- Kim JY, Lee TR, Lee AY. Reduced WIF-1 expression stimulates skin hyperpigmentation in patients with melasma. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(1):191–200.

- Kim SJ, Park JY, Shibata T, Fujiwara R, Kang HY. Efficacy and possible mechanisms of topical tranexamic acid in melasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41(5):480–485.

- Kim HJ, Moon SH, Cho SH, Lee JD, Kim HS. Efficacy and Safety of Tranexamic Acid in Melasma: A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017 Jul 6;97(7):776–781.

- Atefi N, Dalvand B, Ghassemi M, et al. Therapeutic effects of topical tranexamic acid in comparison with hydroquinone in treatment of women with melasma. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7(3):417–424.

- Arshdeep, Kumaran MS. Platelet-rich plasma in dermatology: Boon or a bane? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80(1):5–14.