by Ajay J. Deshpande, MBBS, DVD, DNB

by Ajay J. Deshpande, MBBS, DVD, DNB

Dr. Deshpande is with the Maharashtra Medical Foundation Joshi Hospital in Pune, India.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Background: Acne vulgaris is a self-limiting, chronic inflammatory disorder of the pilosebaceous unit characterized by exacerbations and remissions. It is often the early manifestation of puberty, and in girls it appears relatively early. In women, acne tends to become aggravated during the menstrual period, pregnancy, and in those who are on progesterone. Acne treatment is divided into two parts: topical and systemic. For Grades 1 and 2 acne, topical treatment is sufficient, while for Grades 3 and 4 acne, systemic drugs such as tetracyclines and retinoids are required to control the symptoms. Chemical peeling with glycolic and salicylic acids, cryosurgery with liquid nitrogen or carbon dioxide, and narrowband ultraviolet light are a few of the supportive procedural treatments available for Grades 3 and 4 acne. Objective: The author sought to determine the efficacy and safety of intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy (Magma-F-SR; FormaTK Systems, Tirat Carmel, Israel) in the treatment of Grades 3 and 4 acne as monotherapy in women of child-bearing age. Materials and Methods: One-hundred female patients with Grades 3 and 4 acne were enrolled in this study. All patients were treated with IPL using a 530nm to 1,200nm filter once a week for a total duration of six weeks. Patient and physician scores were assessed at Weeks 1 and 6 after the last treatment. Clinical photographs were also reviewed to determine the degree of efficacy. Adverse effects were noted. Results: Eighty percent of the patients involved in this study reported a significant reduction in lesion count compared to baseline. The adverse events were minimal-to-mild erythema. Conclusion: IPL therapy with 530nm to 1,200nm filter is an effective and safe modality of treatment as monotherapy in managing inflammatory Grades 3 and 4 of acne vulgaris in women of child-bearing age.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris, intense pulsed light therapy, monotherapy

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(4):43–48

Acne vulgaris is a common self-limiting disorder of the pilosebaceous unit that is seen primarily in adolescents.1 Acne is often an early manifestation of puberty. In girls, the occurrence of acne might precede their first menstrual cycle by more than one year. The greatest number of cases are seen during the mid-to-late teenage years of life.2 The key elements in the pathogenesis of acne are follicular epidermal hyperproliferation, excess sebum production, inflammation, and the presence of Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes).3

The disease is characterized by a variety of clinical lesions, although one type of lesion might be predominant. The course of acne can be self-limiting, while the sequelae can be lifelong with pitted or hypertrophic scar formation.3 Comedones and papules form the noninflammatory component, while pustules, nodules, and cysts are the features of the inflammatory variety. Pitted or hypertrophic scarring is more common in patients with inflammatory acne lesions.3 Acne affects primarily the face, neck, upper trunk, and upper arms.

Acne can have a significant impact on the quality of life and psychosocial well-being of the patient.4,5 Therefore, early and aggressive intervention is necessary, especially in the inflammatory variety of acne vulgaris.6 Systemic antibiotics7,8 and retinoids9 are the mainstay of anti-acne management, followed by topical antibiotics,10 benzoyl peroxide,11 and topical retinoids.12 However, in women of child-bearing age, there are limitations in the systemic management of Grades 3 and 4 acne. Antibiotic resistance and adverse effects of topical anti-acne medications are on the rise, so light-based devices and technologies are proving to be effective in the treatment of acne.13,14,15–17 Mohanan et al18 has employed the use of intense pulsed light (IPL) in Indian skin for acne vulgaris with favorable results.Patidar et al19 studied the efficacy of IPL in the treatment of facial acne vulgaris and compared two different fluences. In this study, we assessed the efficacy and safety of IPL therapy (Magma-F-SR; FormaTK Systems, Tirat Carmel, Israel) as a monotherapy in the treatment of Grades 3 and 4 acne in women of child bearing age.

Materials and Methods

One hundred female patients aged 21 to 30 years with Fitzpatrick Skin Types IV to VI were enrolled in this study. Patients who had not received any anti-acne treatment for at least one month prior to enrollment were included. Patients with a history of herpes simplex or those with associated hormonal disorders (e.g., thyroid disorder, polycystic ovary syndrome) were excluded from this study. Patients who were undergoing treatment for infertility were only included after proper consultation with their treating gynecologist. A detailed lesion count was done prior to treatment and at Weeks 3, 6, 9, and 12 of the study. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki on the ethical conduct of medical research. Written consent for participation and use of photos and photographic documentation was completed during each visit. on risk/benefit analysis.

Protective eye glasses were worn during the entire period of the procedure by both the patient and the treating physician. Transparent gel was applied over the entire face. The IPL therapy was performed using a cutoff filter of 530nm to 1,200nm wavelengths in continuous mode with 7.0J/cm² fluence with three milliseconds of pulse width. Six passes were performed over the entire face followed by six passes of two subpulses (double mode) of 14.2J/cm² (7.1J/cm²+7.1J/cm²) fluence over the lesion only. Mild erythema was noted immediately after the treatment. Cooling was achieved with the application of ice packs for 15 minutes immediately after the treatment and followed by the application of topical mometasone furoate 0.01% cream and broad-spectrum sunscreen. The erythema and stinging subsided within 30 minutes. The procedure was repeated each week for a total of six weeks.

Assessment. The efficacy of the IPL therapy was assessed on the scale shown in Table 1, depending upon the lesion count. Patient and physician scores were assessed at Week 1 and Week 6 after the last treatment. A blinded evaluator assessed the efficacy of IPL treatment in all cases at each session for a given patient. Clinical photographs were also reviewed to determine the efficacy.

Results

A total of 100 female patients participated in this study. Out of these 100 patients, seven patients dropped out of the study (4 due to intolerance of the procedure and 3 were lost to follow-up), and the remaining 93 patients completed the study. The treatment sessions were well-tolerated by all of the patients.

Four of the 93 patients who completed the study developed mild erythema after the second treatment session, which subsided completely following seven days of sunscreen protection immediately following the session. There were no long-term or severe adverse events. The immediate cutaneous response was mild-to-moderate erythema and stinging in all patients, which subsided within 30 minutes.

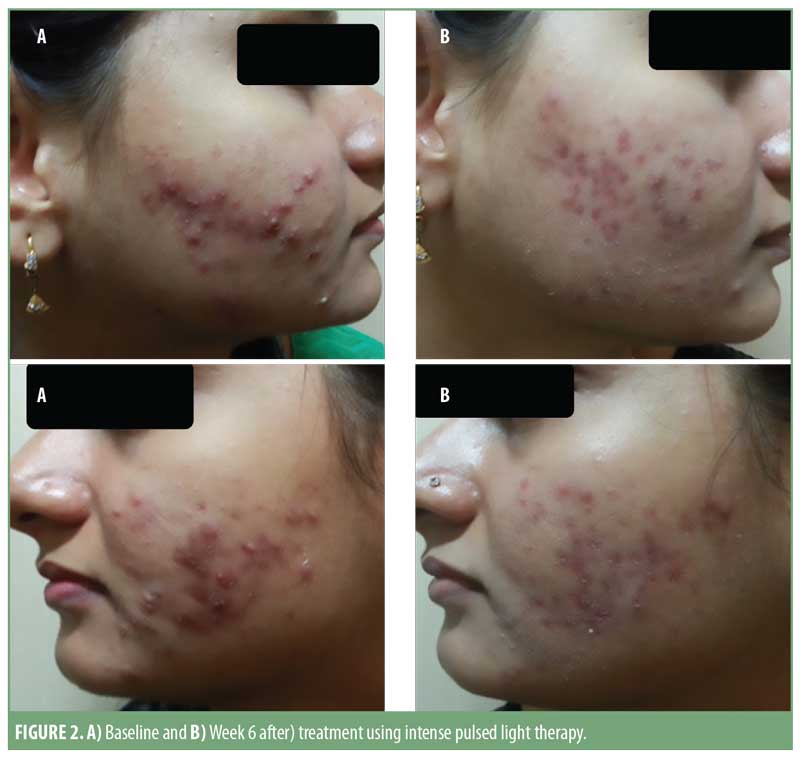

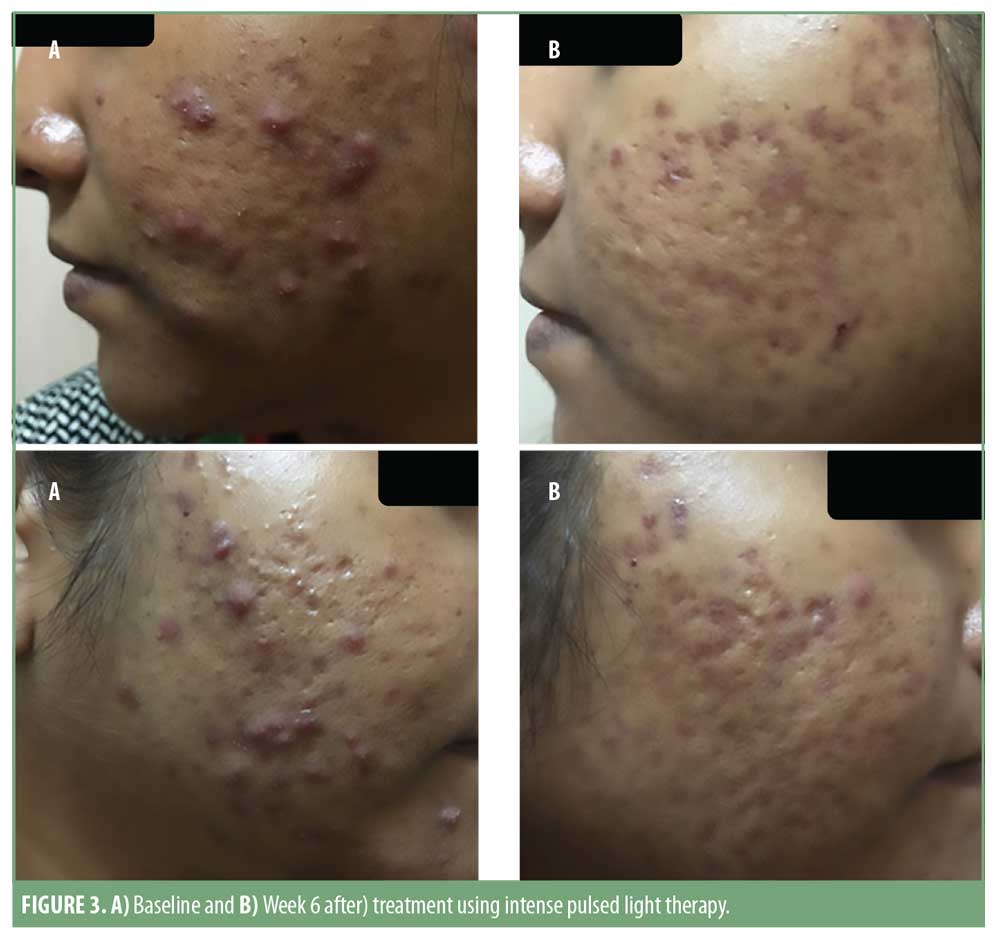

Pre- and post-treatment photographs of three patients are depicted in Figures 1 to 3.

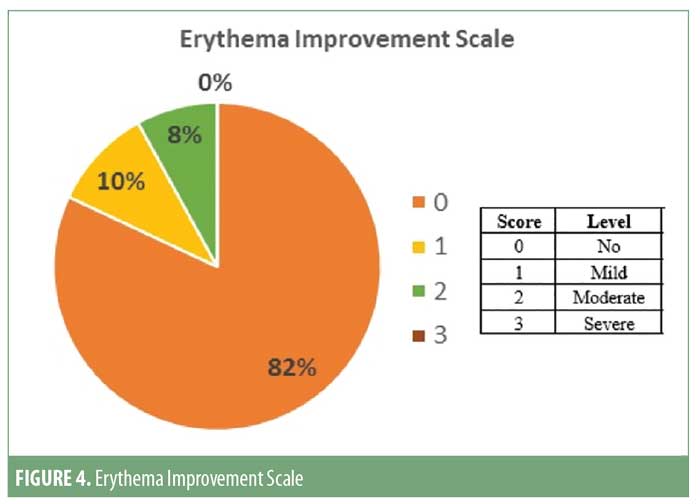

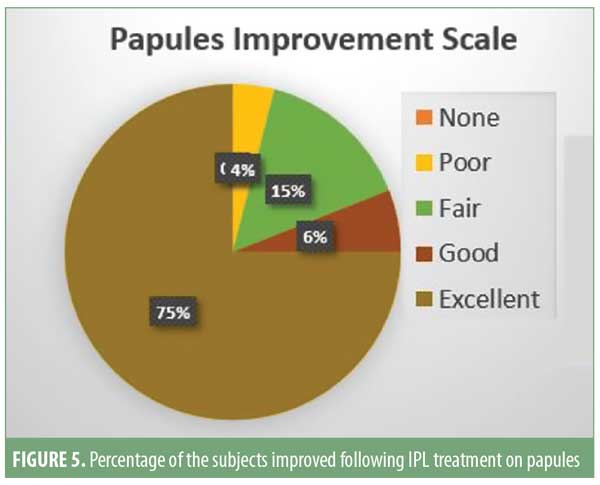

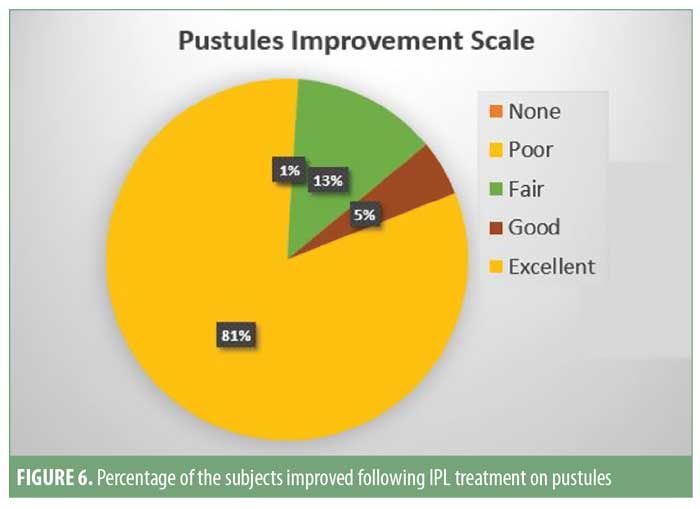

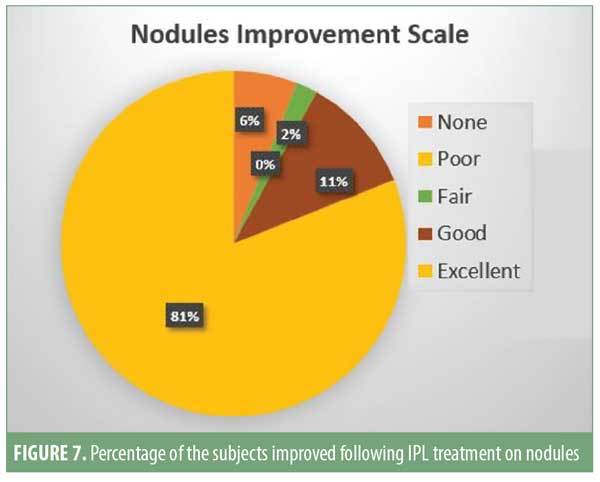

Patient satisfaction scores revealed that 74 of the 93 (approximately 80%) patients noticed good-to-excellent improvement; 10 of the 93 (approximately 11%) patients reported fair-to-good improvement; and seven (approximately 9%) showed poor response. Assessment by a blinded evaluator and pre-and post-photography revealed significant reductions in total lesion count as well as improvements in erythema (Figures 4–7).

Discussion

The lesions caused by acne vulgaris can be either noninflammatory or inflammatory. Black and white comedones (Grades 1 and 2) are noninflammatory lesions, while inflammatory lesions (Grades 3 and 4) are papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts. Scarring is more common in association with the inflammatory variety of acne lesions.20

Overall, the prognosis of acne is favorable. Treatment regimens should be initiated early and be sufficiently aggressive to prevent permanent sequelae. Acne treatment is divided into two parts: topical and systemic. Grades 1 and 2 acne lesions can be managed by topical treatment in the form of either retinoids,21 benzoyl peroxide, topical antibiotics,22 dapsone,23 and azelaic acid.24 However, for Grades 3 and 4, acne systemic drugs are typically needed to prevent scarring. Tetracyclines,25 macrolides,26 trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole,27 dapsone,28 retinoids,29 and oral contraceptives30 are the currently available systemic drugs for acne. Levofloxacin,31 zinc,32 and cephalexin33 have also been tried as treatments for inflammatory acne vulgaris. A short course of oral steroids might be useful for managing fulminant nodular cystic acne. Systemic retinoids are considered teratogenic and thus use is discouraged in women of child-bearing age.34 Also, for individuals with infertility issues, the patients and their treating gynecologists might be reluctant to use any systemic medication, as it might interfere with ovulation. Chemical peels using various alpha and beta hydroxy acids can be used to treat inflammatory acne safely in such cases.35 Narrowband ultraviolet B light,36 pulsed dye laser,37 IPL,38 and light-emitting diodes39 have also been used in the treatment of inflammatory acne with varying degrees of success. Photodynamic therapy using alpha levulinic acid has also been considered effective.40

In our study, we used IPL therapy as the monotherapy for the treatment of inflammatory acne. IPL acts by multiple mechanisms of actions in acne. IPL reduces the inflammation and sebaceous gland size41 and downregulates tumor necrosis alpha,42 thereby reducing the initial lesion count and preventing the formation of new lesions. In our study, we found that the lesion count began decreasing after three sessions and continued to decrease until 12 weeks into the follow-up period. Also, the occurrence of new lesions stopped after three weeks of treatment.

IPL enhances the transforming growth factor beta1/Smad3 signaling pathway in acne-prone skin.43 IPL therapy also induces synthesis of dermal extracellular proteins in vitro as well as increases the amount of dermal collagen and elastic fibers, which reduces risk of scar formation.44,45 This effect was observed in our study, as there was no scar formation and lesions healed uniformly in our patients.

The basic mechanism of action of IPL is selective thermal damage of P. acnes, which produce and store porphyrin. Hyperkeratinization of the pilosebaceous unit due to hormonal changes leads to blocked sebaceous pores. This creates an anaerobic environment for P. acnes that in turn multiply and release porphyrin. IPL penetrates into the hair follicles to target P. acnes by triggering porphyrin activation.46 In telangiectasia and other vascular disorders, IPL also corrects the dilatation of vessels.47 This mechanism helps reduce erythema in inflammatory acne, and this was demonstrated in our patients, who displayed marked reduction of erythema after 3 to 4 sessions of treatment. IPL also has bactericidal activity against P. acnes by triggering porphyrin synthesis. This helps reduce active acne lesions and eruption of new lesions. Our findings correlate with this. In our study, continuous mode had uniform photothermal, photochemical, and photo-immunological effects, which helped ensure longer remission and appeared to aid in preventing new lesions from forming in unaffected skin. The double mode of IPL also produces antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects in the affected skin.

IPL might impart post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring on skin of color when single- or burst-pulse modes are used.48 Considering this, we used continuous mode followed by double-pulse mode in our study. In both modes (continuous and double), the pulse width was significantly less than the TRT value (>10ms), which improves safety of the treatment, considering the photo-type, without compromising the density of the emitted energy. This helps maintain high efficacy and precision in the light–tissue interaction.

The unique feature of our study is that IPL therapy was applied as a monotherapy for inflammatory acne vulgaris, keeping fluence, pulse mode, and frequency of the sessions constant with satisfactory results. This is the first study to our knowledge in which energy was delivered in continuous and double-pulse modes, one after the other, on the same day for six treatment sessions without any adverse effects. There have been a few studies assessing the use of IPL therapy in inflammatory acne in the literature; however, our study included the largest cohort of patients (n=100).

Conclusion

IPL therapy with a 530nm to 1,200nm filter, delivering short and dense energy pulses and using the continuous and double-pulse modes, was demonstrated to be safe and effective as a monotherapy for the treatment of Grades 3 and 4 acne in women of child bearing age.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge Sharad Mutalik, MBBS, DVD, head of the Department of Dermatology at Maharashtra Medical Foundation Joshi Hospital in Pune, India, for his valuable guidance in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Williams C, Layton AM. Persistent acne in women: Implications for the patient and for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(5):281–290.

- Lucky AW, Biro FM, Huster GA, et al. Acne vulgaris in premenarchal girls. An early sign of puberty associated with rising levels of dehydroepiandrosterone. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(3):308–314.

- Zaenglein AL, Graber EM, Thiboutot DM. Acne vulgaris and acneiform eruptions. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology In General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2008: 690–703.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(5):846–850.

- Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, et al. The quality of life in acne: a comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140(4):672–676.

- Haider A, Shaw JC. Treatment of acne vulgaris. JAMA. 2004;292(6):726–735.

- Leyden JJ. Therapy for acne vulgaris. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1156 –1162.

- Skidmore RA, Kovach R, Walker C, et al. Effects of subanti-microbial dose of doxycycline in treatment of moderate acne. Arch Dermatol. 2003; 139:459–464.

- Ortonne JP. Oral isotretinoin treatment policy. Do we all agree?. Dermatology. 1997;195 Suppl 1:34–37; discussion 38–40.

- Weiss JS. Current options for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Paediatr Dermatol. 1997;14(6):480–488.

- Bojar RA, Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT. The short-term treatment of acne vulgaris with benzoyl peroxide: effects on the surface and follicular cutaneous microflora. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(2):204–208.

- Gollnick H, Schramm M. Topical therapy in acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11 Suppl 1:S8–S12; discussion S28–S9.

- Ross JI, Snelling AM, Carnegie E, et al. Antibiotic-resistant acne: lessons from Europe. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(3):467–478.

- Sinnott SJ, Bhate K, Margolis DJ, Langan SM. Antibiotics and acne: an emerging iceberg of antibiotic resistance?. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(6):1127–1128.

- Rai R, Natarajan K. Laser and light based treatments of acne. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(3): 300–309.

- Babilas P. Light-assisted therapy in dermatology: the use of intense pulsed light (IPL). Med Laser Appl. 2010;25:61–69.

- Elman M, Lebzelter J. Light therapy in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2 Pt 1):139–146.

- Mohanan S, Parveen B, Annie Malathy P, Gomathi N. Use of intense pulsed light therapy for acne vulgaris in Indian skin—a case series. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(4):473–476.

- Patidar MV, Deshmukh AR, Khedkar MI. Efficacy of intense pulsed light therapy in the management of facial acne vulgaris: comparison of two different fluencies. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61(5) 545–549.

- Tank J, Kang S, Leyden J. Prevalence and risk factors of acne scarring among patients consulting dermatologists in the United States. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(2): 97–102.

- Leyden JJ, Tanghetti EA, Miller B, et al. Once-daily tazarotene 0.1 % gel versus once-daily tretinoin 0.1 % microsponge gel for the treatment of facial acne vulgaris: a double-blind randomized trial. Cutis. 2002;69(2 Suppl):12–19.

- Eady EA, Bojar RA, Jones CE, et al. The effects of acne treatment with a combination of benzoyl peroxide and erythromycin on skin carriage of erythromycin-resistant propionibacteria. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134(1):107–113.

- Lucky AW, Maloney JM, Roberts J, et al. Dapsone gel 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris: safety and efficacy of long-term (1 year) treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6(10):981–987.

- Gollnick H, Graupe K. Azelaic acid for the treatment of acne: comparative trials. J Dermatol Treat. 1989;1:27–30.

- Goulden V. Safety of long-term high-dose minocycline in the treatment of acne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134(4): 693–695.

- Fernandez-Obregon AC. Azithromycin for the treatment of acne. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39(1):45–50.

- McCarty M, Rosso JQ. Chronic administration of oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for acne vulgaris. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4(8):58–66.

- Bettoli V, Sarno O, Zauli S, et al. [What’s new in acne? New therapeutic approaches]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137 Suppl 2:S81–S85. Article in French.

- Scalglion R, Dosirello G, Pazzaglia A. [Inflammatory acne resistant to conventional therapy. Efficacy and tolerability of isotretinoin]. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1989;124(3):XIII–XIX. Article in Italian.

- Harper JC. Use of oral contraceptives for management of scne vulgaris: Practical considerations in real world practice. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34(2):159–165.

- Kawada A, Wada T, Oisa N. Clinical effectiveness of once-daily levofloxacin for inflammatory acne with high concentrations in the lesions. J Dermatol. 2012;39(1):94–69.

- Gessert CE, Bamford JT, Haller IV, Johnson BP. The role of zinc in rosacea and acne: further reflections. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(1):128–129.

- Fenner JA, Wiss K, Levin NA. Oral cephalexin for acne vulgaris: clinical experience with 93 patients. Paeditr Dermatol. 2008;25(2):179–183.

- Stern RS, Rosa F, Baum C. Isotretinoin and pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10(5 Pt 1):851–854.

- Dayal S, Amrani A, Sahu P, Jain VK. Jessner’s solution vs. 30% salicylic acid peels: a comparative study of the efficacy and safety in mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16(1):43–51.

- Rassai S, Rafeie E, Ramirez-Fort MK, Feily A. Adjuvant narrow band UVB improves the efficacy of oral azithromycin for the treatment of moderate to severe inflammatory facial acne vulgaris. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7(3):151–154.

- Voravutinon N, Rojanamatin J, Sadhwani D, et al. A comparative split-face study using different mind purpuric and subpurpuric fluence level of 595-nm pulsed dye laser for treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(3):403–409.

- Jiang LI. Clinical study and evaluation of treatment of face acne vulgaris with intense pulsed light. Chin J Dermatol Venerol Integr West Med. 2009;8:6.

- Sadick N. A study to determine the effect of combination blue (415 nm) and near-infrared (830 nm) light emitting diode (LED) therapy for moderate acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11(2):125–128.

- Hongcharu W, Taylor CR, Chang Y, et al. Topical ALA photodynamic therapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115(2):183–192.

- Barakat MT, Maftah NH, EI Khayyat, Abdelhakim ZA. Significant reduction of inflammation and sebaceous gland size in acne vulgaris lesions after intense pulsed light treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30(1): e12418.

- Taylor M, Porter R, Gonzalez M. Intense pulsed light may improve inflammatory acne through TNF-alpha down-regulation. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16(2):96–103.

- Ali MM, Porter RM, Gonzalez M. Intense pulsed light enhances transforming growth factor beta1/Smad3 signaling in acne-prone skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12(3):195–203.

- Cureda-Gallindo E, Diaz-Gill G, Palomar-Gallego MA, Linaras-garcia, Vadecasas R: Intense pulsed light therapy induces synthesis of dermal extracellular proteins in vitro. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(7):1931–1939.

- Cao Y, Huo R, Feng Y, et al. Effects of intense pulsed light on the biological properties and ultrastructure of skin dermal fibroblasts: potential roles in photoaging. Photomed Laser Surg. 2011;29(5):327–332.

- Ashkenazi H, Malik Z, Harth Y, Nitzan Y. Eradication of Propionibacterium acnes by its endogenous porphyrins after illumination with high intensity blue light. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003; 35:17–24.

- Liu J, Liu J, Ren Y, et al. Comparative efficacy of intense pulsed light for different erythema associated with rosacea. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16(6):324–327.

- Kumaresan M, Srinivas CR. Efficacy of IPL in treatment of acne vulgaris: Comparison of single-and burst pulse mode in IPL. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55(4):370–372.