by Lauren C. Cook, MD; Courtney Hanna, MPH; Galen T. Foulke, MD; and Elizabeth V. Seiverling, MD

by Lauren C. Cook, MD; Courtney Hanna, MPH; Galen T. Foulke, MD; and Elizabeth V. Seiverling, MD

Drs. Cook, Foulke, and Seiverling are with the Department of Dermatology, Dr. Seiverling is also with the Department of Family and Community Medicine, and Ms. Hanna is with the Penn State College of Medicine—all with the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Background: Dermoscopy is well established as a tool to improve the detection of cancerous skin growths. Published data suggest that dermoscopy might be useful in evaluating inflammatory dermatoses and in distinguishing between rashes and skin cancer. Objective: The authors sought to review the published literature regarding use of dermoscopy in the evaluation of inflammatory skin conditions. Methods: Using a systematic approach, the authors performed a literature search using the names of 146 inflammatory dermatoses and pairing each one separately with the search terms dermoscopy, dermatoscopy, and epiluminescence microscopy. Results: After eliminating those papers that did not meet inclusion requirements, the authors identified 201 studies for their review, with the majority consisting of case reports. The most commonly studied inflammatory conditions were psoriasis, lupus, and lichen planus. There was congruence among the studies identified in terms of the most common dermoscopic findings for each of these diseases. Conclusions: The use of dermoscopy in the evaluation of inflammatory dermatoses is a promising option. However, more rigorous studies are needed to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the dermoscopic findings for many inflammatory skin conditions.

Keywords: Dermoscopy, inflammatory dermatoses, psoriasis, lupus, lichen planus

Dermoscopy is a noninvasive technique used to magnify and visualize structures on and beneath the skin surface. Multiple studies have shown the use of dermoscopy increases diagnostic accuracy when analyzing skin growths.1,2 More recently, the use of dermoscopy has expanded to include the evaluation of rashes and skin infections.3 The purpose of this research was to review the published literature regarding the use of dermoscopy in the evaluation of inflammatory skin conditions.

Methods

Two reviewers (LC and CH) searched Ovid MEDLINE separately. The search terms included the names of 146 inflammatory dermatoses compiled from the table of contents of Dermatology by Bolognia et al4 and Inflammatory Skin Disorders by Plaza and Prieto.5 Each inflammatory dermatosis was separately paired with the ancillary search terms dermoscopy, dermatoscopy, and epiluminescence microscopy, respectively. Articles published between 1996 and 2016 were reviewed. Only articles written in the English language were included. We did not include articles that focused solely on confocal microscopy. Duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were evaluated, and articles that did not mention dermoscopy of any inflammatory dermatoses were excluded. Any discrepancy on whether to include an article was determined by a third reviewer (EVS).

Results

The initial search yielded 316 articles. After exclusions, 201 papers were included in the review. The top three inflammatory dermatoses reported were psoriasis (31 articles), cutaneous lupus (26 articles), and lichen planus (23 articles). Of these 54 articles, the majority were case reports (32 articles), followed by cross-sectional studies (14 articles), and case series (8 articles).

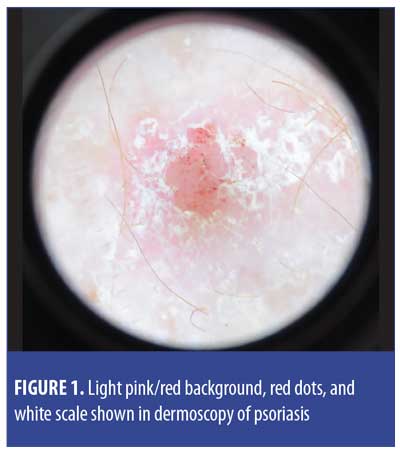

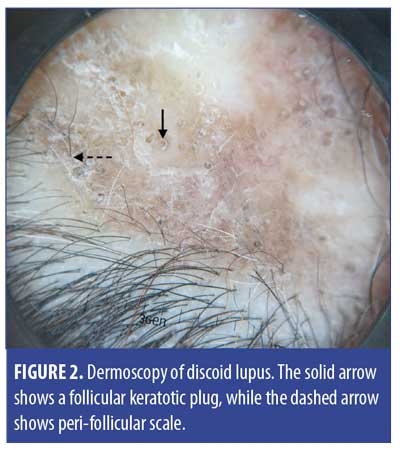

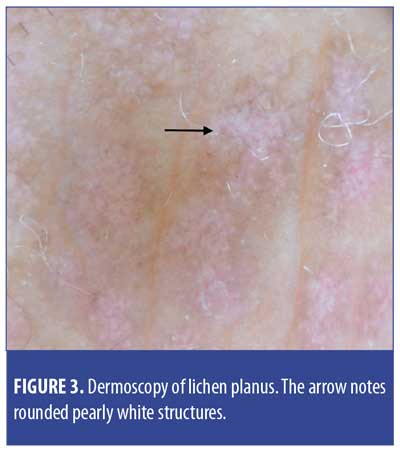

The most commonly reported dermoscopic findings of psoriasis were red dots, red globules, glomerular vessels (also known as twisted capillary loops), red globular rings, and white scale (Figure 1). Of the 26 articles discussing the dermoscopy of lupus, most focused on discoid lupus of the scalp. Common dermoscopic findings of discoid lupus were yellow follicular keratotic plugs, follicular red dots, blue-gray dots, and peri-follicular scale (Figure 2). Common dermoscopic findings of lichen planus were polymorphic pearly white structures (rounded, arboriform, reticular, annular), radial capillaries, and blue-gray granules (Figure 3). In addition, peri-follicular scale was seen in lichen planopilaris.

Discussion

Psoriasis, lupus, and lichen planus were found to be the most commonly reported inflammatory skin conditions with respect to dermoscopy. Sensitivity and specificity data were reported for psoriasis, but not for lichen planus or lupus. However, unique features of lupus and lichen planus have been repeatedly reported. For plaque psoriasis, the combination of regularly distributed dotted vessels with a light red background and diffuse white scales was reported to be 88.0-percent specific and 84.9-percent sensitive.6 Another study looking at how to differentiate basal cell carcinoma from psoriasis showed that there was a 99-percent diagnostic probability that the lesion was psoriasis if it had a homogeneous vascular pattern, red dots, and a light red background.7

The highly specific and sensitive dermoscopic findings of psoriasis are very helpful when differentiating psoriasis from basal cell carcinoma.7–10 In contrast to the aforementioned dermoscopic findings of psoriasis, basal cell carcinoma has the following characteristics under dermoscopy: shiny white structures, ulceration, blue-gray ovoid nests, spoke wheel-like structures, and arborizing vessels.10 While the clinical distinction between the two diagnoses is sometimes difficult, their respective dermoscopic findings are quite different. Appropriate treatment is dependent upon accurate diagnosis. Furthermore, if basal cell carcinoma is detected in a patient with psoriasis, treatment modalities such as ultraviolet light or tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors might need to be adjusted or discontinued. Therefore, in a patient with psoriasis, new scaly pink patches are best analyzed with dermoscopy to determine if the patches are a manifestation of psoriasis or a new basal cell carcinoma.

Dermoscopy is also potentially useful in expediting care for those with inflammatory skin conditions. For example, patients with psoriatic arthritis sometimes have subtle or minimal skin disease. Dermoscopy might support a diagnosis of psoriasis instead of a different inflammatory condition. Additionally, dermoscopy might prove to be useful in the diagnosis of discoid lupus. The dermoscopic findings of discoid lupus on the scalp have been repeatedly reported. If the clinical morphology and dermoscopy findings are consistent with discoid lupus, there might not be a need for skin biopsy. Thus, dermoscopy has the potential to expedite the initiation of therapies. If more is published on the sensitivity and specificity of the dermoscopic findings of psoriasis, lichen planus, and lupus, fewer biopsies might be needed to obtain accurate diagnoses. As a result, dermoscopy can potentially reduce risk to the patient, expedite treatment, and lower medical costs.

Conclusion

Dermoscopy has been widely studied in differentiating benign and malignant skin lesions and is now expanding its role as a tool for the evaluation of inflammatory skin conditions. Lallas et al3 reported the wide range of inflammatory and infectious conditions in which dermoscopy has the potential to be helpful. We found many reports on the use of dermoscopy in psoriasis, lupus, and lichen planus, but were unable to appraise the quality of these findings due to the paucity of rigorous studies. The lack of original research on this topic makes it difficult to move forward with evidence-based recommendations for the use of dermoscopy in identifying inflammatory conditions, despite a plethora of unique findings on the use of dermoscopy for each condition. In order for the benefits of dermoscopy in the evaluation of rashes to be validated, reports on the sensitivity and specificity of dermoscopic findings for inflammatory conditions other than psoriasis are necessary.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(4):41–42

References

- Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, Binder M. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3(3):

159–165. - Vestergaard M, Macaskill P, Holt P, Menzies S. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(3):669–676.

- Lallas A, Giacomel J, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy in general dermatology: practical tips for the clinician. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(3):514–526.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Plaza J, Prieto V. Inflammatory Skin Disorders. 1st ed. New York, NY: Demos Medical; 2012.

- Lallas A, Kyrgidis A, Tzellos TG, et al. Accuracy of dermoscopic criteria for the diagnosis of psoriasis, dermatitis, lichen planus and pityriasis rosea. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(6):1198–1205.

- Pan Y, Chamberlain A, Bailey M, et al. Dermatoscopy aids in the diagnosis of the solitary red scaly patch or plaque–features distinguishing superficial basal cell carcinoma, intraepidermal carcinoma, and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(2):268–274.

- Menzies S, Westerhoff K, Rabinovitz H, et al. Surface microscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(8):1012–1016.

- Altamura D, Menzies S, Argenziano G, et al. Dermatoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: morphologic variability of global and local features and accuracy of diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(1):67–75.

- Marghoob A, Malvehy J, Braun R, eds. An Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012.