J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3):14–16.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3):14–16.

by Shino Bay Aguilera, DO; Mehreen Hall, DO; Dayana Carolina Suárez Carvajal, MD; and Andres Gaviria, MD

Dr. Aguilera is with NOVA Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Dr. Hall is with Larkin Community Hospital Palm Springs Campus in Hialeah, Florida. Dr. Carvajal is with Rosario University in Bogota, Colombia. Dr. Gaviria is with Universidad CES in Medellin, Colombia

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Ethnic groups can be differentiated through certain anatomical characteristics, including the morphological features of their skulls. Little information is available on the craniofacial measures of the Mestizo face. Over time, the upper third of the Mestizo face can develop a greater frontal concavity of the forehead, making the eyebrows drop and giving the face a more masculine appearance. Understanding the skeletal and vascular anatomy of this population group is the foundation for proper aesthetic rejuvenation of the upper third of the face. The purpose of this article is to present an advanced injection technique utilizing a low-viscosity and low-G prime filler to correct exaggerated frontal concavity. Using just 1 to 2mL of product, patients can be safely treated with a high satisfaction rate and a cosmetic result capable of lasting up to three years.

Keywords: Cosmetic injection, craniofacial, Mestizo face

An indigenous population lived in America before their discovery by the Spaniards in 1492. In the Empire of the Spanish crown during the 15th century until the 19th century, there was a division of social classes based on the mixture of three basic ethnic groups (black, white and indigenous) called the caste system. This system classified people according to their descent. In this way, Mestizo is defined as a descendant of an indigenous Native American and a European white.1 Mestizos comprise the great majority of Latin Americans, found in parts of Ecuador, Paraguay, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Peru.

No population group is biologically homogeneous. One of the anatomical characteristics that differentiates ethnic groups from one another is the morphology of their skeletons, particularly their skulls.2 Most studies of forensic anthropology and morphometric analysis of the skull highlight the differences in craniofacial forms between Caucasian, Afrodescendant and Asian men and women.3 Further, a study in American Caucasians and Africans found that sex, but not size, had a significant influence on cranial shape. Moreover, the average cranial size of men was shown to be different than that of women, indicating that a significant sexual dimorphism exists.4

The frontal bone is useful in determining the complete craniofacial form and its morphological characteristics are a tool in the therapeutic approach of the upper third of the face. In approaching aesthetic forehead contouring, it is important to recognize differences between sex and ethnic groups.

Quantitative methods were developed to assess the inclination of the frontal bone with three-dimensional cranial models, which demonstrated that the male skull has a more prominent glabellar region relative to a female’s skull together with a lower and more sloped forehead.5

Some features of forehead size have been described in different populations. A study that included 1,470 subjects from five regions around the world (Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and North America) used various anthropometric measurements to determine the morphologic characteristics of the craniofacial complex in four ethnic groups. The authors found no differences in forehead height when comparing Caucasian, African, and Asian participants with native North American participants. Only in Croatian male and Iranian participants was the forehead height found to be significantly smaller than that of the other ethnic groups studied.3 Mongolian or Asian foreheads have less volume in the fat compartments, have lower-set brows, and skulls that are more concave or flatter. Chinese heads have been described as rounder and flatter than Caucasian heads, both in the occipital region and in the forehead.6

Mestizo facial characteristics include a broad face, thicker skin, greater downward sloping of the lateral eyebrows, upper eyelid hooding, prominent malar eminences, slightly retrusive chins, and smaller noses with poor nasal tip support.7 There is little information about the craniofacial measures in Mestizos and how the environment and genetics influence the shape of their skulls.

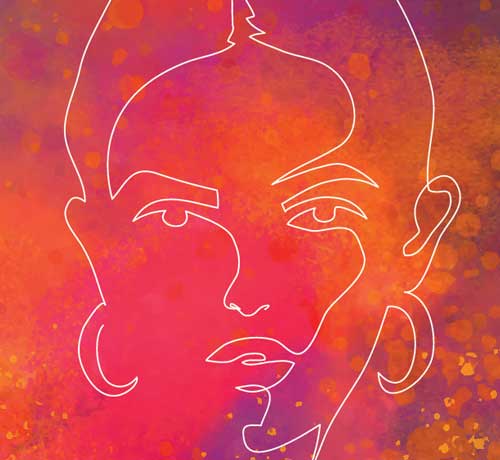

Mestizos have foreheads with characteristics similar to those mentioned as existing in Asian foreheads. In the author’s daily practice, the Mestizo forehead has been found to differ from those of various ethnic groups by a greater frontal concavity, which generates unfavorable shadows in the upper facial third, appearance of skeletonization of the forehead, greater protrusion of the supraciliary arches, drooping eyebrows, collapse at the bridge of the nose, and a masculinization effect of a female face (Figure 1). These racial anatomic differences can also contribute to premature aging in the upper third of the face.

Craniofacial measures and indices have been applied in the area of medicine for anatomical, surgical, and diagnostic approaches and to study cranial diseases or deformities. In aesthetic facial rejuvenation, these parameters can be a fundamental tool for the evaluation and therapeutic approach not only of the upper facial third, but also of other areas with different genetic or ethnic characteristics, such as the orbital opening, jaw shape, and projection of the cheekbones or nasal form. Using the understanding of the aging Mestizo forehead, this article provides a safe and therapeutic approach for facial upper third rejuvenation.

Methods

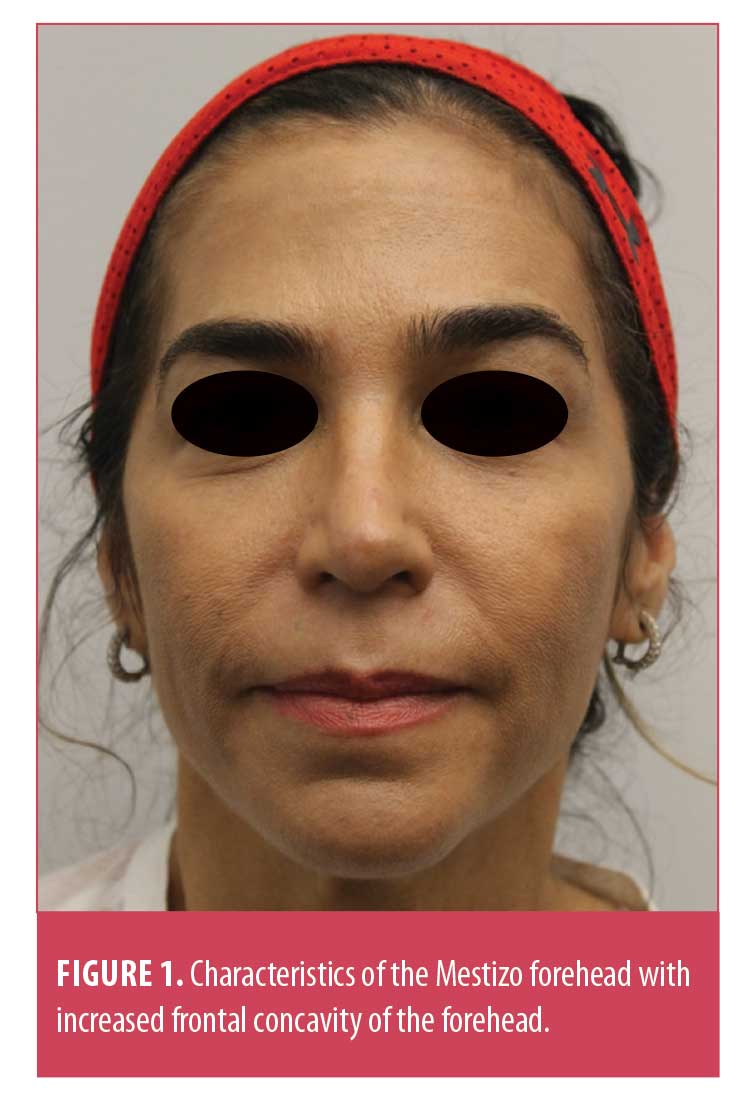

In addition to understanding the skeletal structure, treating the frontal area of a Mestizo individual requires an astute knowledge of the vascular anatomy in the upper third of the face for proper injection technique and to minimize the risk of complications. Three important vascular structures that course the frontal concavity include branches off the ophthalmic artery (i.e., supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries) and the superficial temporal artery, inclusive of its branches (Figure 2). Bilaterally, the supraorbital artery and nerve pass through the supraorbital foramen and the superficial temporal artery, which then courses superiorly and medially along the temporal region and anastomoses with the supraorbital artery. The supratrochlear artery and nerve are medial to the supraorbital artery and complete the glabellar complex with limited collateral circulation.8 Sensory innervation of the frontal region comes from the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves, which stem from the trigeminal nerve.

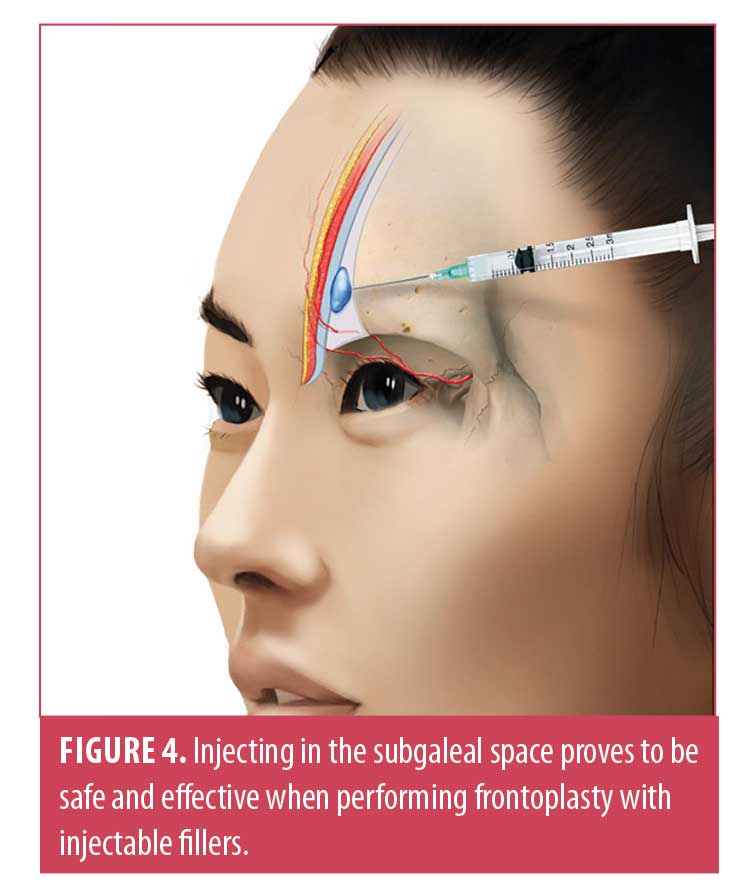

Considering these vascular structures facilitates proper technique and minimization of vascular occlusion. Arterial occlusion can lead to ischemia, ulceration, scarring, and, in severe cases vision loss from retrograde flow of filler from the supratrochlear, supraorbital, and dorsal nasal arteries. This can occur not only through intra-arterial injection of product but also as a result of vascular injury during the procedure as well as compression of the blood supply via adjacent filler placement. Nerve injury is also a potential complication by which patients can experience headaches, neuralgia, and paresthesias to the frontal, parietal, and occipital regions.9 Injecting the subgaleal space and aspirating prior to injection can minimize these risks. However, an astute injector must evaluate the signs and symptoms of vessel occlusion to treat such promptly. After evaluating the vascular anatomy and understanding the bony formation of the Mestizo forehead, an injector can then safely conduct rejuvenation of the upper third of the face.

The objective in treating the forehead is to bring harmony to the face by correcting the hollowing of the forehead, lessening the effects of bossing of the brows, and creating a natural result of facial rejuvenation volume restoration. The author typically uses 0.8cc of 1% lidocaine without epinephrine added to a Vycross hyaluronic acid syringe (Allergan, Dublin, Ireland). This blend allows for a lower viscosity to fill a larger field and supports effective flow in the tight subgaleal space. The blend also creates a lower G prime hyaluronic acid filler to maintain the product’s cohesivity and uniformly volumize the forehead. This blend can last for up to three years in the forehead.

Procedure. What follows henceforth is a description of a safe, stepwise cannula approach to filling the frontal concavity in the Mestizo population. First, one should define the various entry points for injection by first palpating the temporal crest as a landmark. Depending on the depth of the frontal concavity, 2 to 4 entry points are made bilaterally along the temporal fusion line. An X should be placed along the entry points for reference, which will be removed later in the third step.

Second, a single, small bolus of lidocaine 1% with epinephrine (to prevent bleeding) is placed at each entry point to anesthetize where injections will occur. Then, the area of treatment is sterilized with a chlorhexidine sponge or hypochlorous acid, and entry-point markings are subsequently removed to create a clean environment for injection.

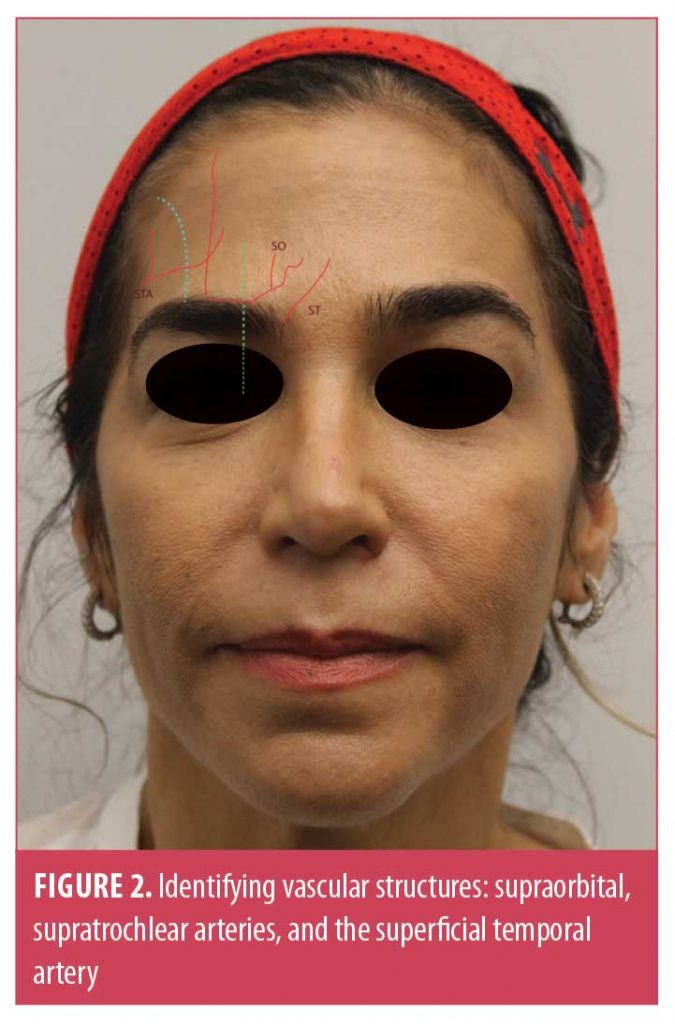

Finally, a novel supraperiosteal technique of hydrodissection is adopted in the placement of hyaluronic acid filler.10 With a 21-gauge needle, entry points are made in the epidermis. Using a rigid 25-gauge, 2-in autoclavable cannula, the hyaluronic acid blend is injected into the subgaleal plane by holding the frontalis muscle between the thumb and forefinger to allow for a more comfortable positioning of the cannula in the subgaleal space. It is imperative to know where the tip of the cannula is at all times prior to product deposition. When at the appropriate depth of injection and prior to injecting product, one should retract the cannula 1 to 2mm in the event that the cannula tip is near a vascular structure so as to avoid compromise. Retrograde linear threads of product are then placed along the frontal concavity until the deficit cannot be visualized any further (Figure 3). The volume of the Vycross filler and lidocaine blend will lift up and dissect the tight plane between the gallium and the pericranium. The expansion of this space with product will help to move important vascular structures away from the cannula, thereby creating a safer plane of injection. With gentle fingertip manipulation, the blend is massaged laterally to ensure that the hyaluronic acid injected will infuse uniformly without physical force other than manual sculpting (Figure 4). Continuous patient feedback during injection is encouraged to assess for signs and symptoms of nerve impingement or vascular compromise. Use of 1- to 2-mL syringes may be sufficient to greatly improve the frontal concavity (Figure 5).

Conclusion

Even though more studies describing the craniofacial morphological differences in Mestizos are needed, the upper third of the Mestizo face is very similar to the forehead of a Mongolian or Asian individual, which may be seen as a genetic disadvantage because of the reduced amount of volume on the fat compartments, low-set brows, and more concave frontal bone or flatter forehead. With aging, due to these differences, the Mestizo face often loses the soft tissue aperture and becomes masculinized. With proper anatomical training, while adopting the above step-by-step procedure, this technique will create a natural result of facial rejuvenation volume restoration in the upper third of the face.

The use of neurotoxin to treat the upper third in combination with a safe technique with injectable filler must be considered for an optimal and natural treatment in Hispanic foreheads.

References

- Brooks D. Criollos, mestizos, mulatos o saltapatrás: cómo surgió la división de castas durante el dominio español en América. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-41590774. Accessed February 27, 2021.

- Krogman WM, Iscan MY. The Human Skeleton in Forensic Medicine. 2nd ed. Springfield IL: Charles Thomas; 1986.

- Farkas LG, Katic MJ, Forrest CR, et al. International anthropometric study of facial morphology in various ethnic groups/races. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16(4):615–646.

- Kimmerle EH, Ross A, Slice D. Sexual dimorphism in America: geometric morphometric analysis of the craniofacial region. J Forensic Sci. 2008;53(1):54–57.

- Petaros A, Garvin HM, Sholts SB, et al. Sexual dimorphism and regional variation in human frontal bone inclination measured via digital 3D models. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2017;29:53–61.

- Ball R, Shu C, Xi P, et al. A comparison between Chinese and Caucasian head shapes. Appl Ergon. 2010;41(6):832–839.

- Cobo R, Garcia C. Aesthetic surgery for the Mestizo/Hispanic patient: special considerations. Facial Plast Surg. 2010;26(2):164–173.

- Emer J, Waldorf H. Injectable neurotoxins and fillers: there is no free lunch. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29(6):678–690.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. JUVÉDERM® VOLUMA™ XC – P110033/S047. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/recently-approved-devices/juvedermr-volumatm-xc-p110033s047. Accessed February 27, 2021.

- Glaich AS, Cohen JL, Goldberg LH. Injection necrosis of the glabella: protocol for prevention and treatment after use of dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(2):276–281.

- Chao YYY. Saline Hydrodissection: A novel technique for the injection of calcium hydroxylapatite fillers in the forehead. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(1):133–136.