J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(9 Suppl 1):S24–S25

by Archana M. Sangha, MMS, PA-C

by Archana M. Sangha, MMS, PA-C

Ms. Sangha is a medical science liaison for Incyte in Wilmington, Delaware. Prior to that, she spent over a decade as a dermatology PA specializing in general, surgical, and cosmetic dermatology. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Physician Assistants in Alexandria, Virginia. She is also Immediate Past President of the Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: Ms. Sangha is an employee of Incyte in Wilmington, Delaware.

Keloids are a result of abnormal wound healing due to skin trauma or inflammation. They affect patients with skin of color (SOC) at a higher rate than white patients. Dark-skinned patients are 15 times more likely to form keloids,1 and in patients of African, Asian, or Hispanic descent, incidence rates are as high as 16 percent.2 A familial history also increases the risk of keloid development. One study in patients of Afro-Caribbean descent showed that more than half of patients with keloids had a positive family history of keloidal scarring.3 While not dangerous, keloids are often symptomatically and cosmetically bothersome for patients. One study found that 86 percent of patients with keloids reported pruritis and 46 percent reported pain.4 Another study showed that 65 percent of patients suffered psychological impact due to their keloids.5 This article will review the most common procedural treatment approaches to keloids and nuances to consider when treating SOC patients.

Diagnostic Considerations

Hypertrophic scar vs. Keloid. Unlike hypertrophic scars, which do not extend beyond the initial area of injury, keloidal tissue always extends beyond the initial site of trauma. Another clinical difference is that hypertrophic scars do not project above the skin surface beyond 4mm while keloids often do. Hypertrophic scars often form within 4 to 8 weeks following skin injury and grow rapidly for up to six months before regressing. Conversely, keloids can take years to develop following initial injury and do not spontaneously regress;6 thus, obtaining a patient’s history is a critical component of the diagnostic process. Hypertrophic scars favor the neck, presternum, shoulders, knees, and ankles, whereas keloids have a predilection for the chest, shoulders, posterior neck, upper back and earlobes.

Treatment Approaches

Several procedural options exist for the treatment of keloids, although none have been consistently successful. Thus, when considering which treatment option(s) to implement, it’s important to take into account the patient’s unique clinical history and clinical findings, such as the size and location of keloid, age of patient, impact on the patient’s quality of life, and the patient’s treatment goals.

Intralesional corticosteroids. Intralesional corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy for keloid management. Intralesional triamcinolone 10-40 mg/cc is administered once or twice a month for several visits until desired outcome is achieved. Injection placement should be in the mid-dermis to avoid atrophy of the epidermis. The therapeutic response is variable, with 50- to 100-percent regression reported.7 Recurrence rate was found to be 33 percent at one year and 50 percent at five years.7 Common adverse effects include skin and subcutaneous fat atrophy, hypopigmentation, and telangiectasia. It’s important to discuss these side effects and patient expectations of treatment outcome prior to initiation of treatment.

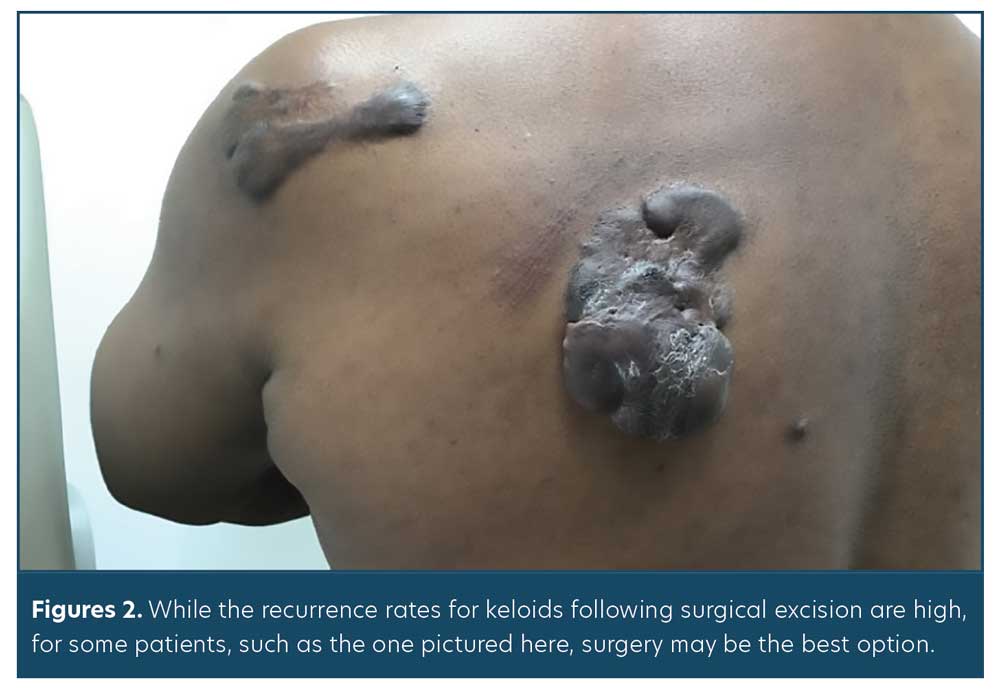

Surgery. Consideration of surgery for keloid excision should be weighed cautiously. Recurrence rates following surgical excision are high, ranging from 45 to 100 percent.8 Use of adjuvant treatment, such as intralesional corticosteroid injection or radiation therapy, should be considered to minimize recurrence rates. For example, recurrence rates have been shown to drop to 22 percent when radiation therapy follows surgical excision.9 Counseling patients on surgical risks, such as potential worsening of existing keloid or new keloid formation, is imperative. While the decision for surgical excision is not an easy one, for some patients (Figure 2), this can arguably offer the best chance at returning to functional normalcy.

Lasers. Numerous laser options exist for keloid treatment. Nonablative lasers commonly used include the 585nm pulsed dye laser (PDL) and the Nd:YAG laser. These lasers work by inducing thermal injury to the keloid’s microvasculature and have been shown to induce flattening and regression of keloids.10 The 585nm PDL has been shown to have success rates ranging from 57 to 83 percent.11 Because the 585nm PDL also targets melanin, it has an increased risk of causing pigmentary changes.12 The Nd: YAG laser is thought to directly suppress fibroblast collagen progression. One study using the 1064nm Nd:YAG laser showed no pigmentary alterations in SOC patients.13 Furthermore, patients saw clinical improvement in their keloids, which was enhanced when combined with intralesional steroids.13 Another study comparing efficacy of PDL versus Nd:YAG laser showed no statistically significant differences between the two modalities. Both lasers were shown to significantly improve the appearance of keloids.14

Conclusion

Despite many treatment options, keloids continue to pose a challenge for clinicians. Given the significantly higher incidence rate among SOC populations, compared to lighter-skinned individuals, clinicians should be aware of the potential treatment side effects that impact this population. Having a risk-benefit conversation with patients prior to deciding upon a treatment plan is critical for optimal patient satisfaction.

References

- Brissett AE, Sherris DA. Scar contractures, hypertrophic scars, and keloids. Facial Plast Surg 2001;17:263–272.

- Robles DT, Berg D. Abnormal wound healing: keloids. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(1):26–32.

- Bayat A, Arscott G, Ollier WER, et al. Keloid disease: clinical relevance of single versus multiple site scars. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:28–37.

- Lee SS, Yosipovitch G, Chan YH, et al. Pruritus, pain, and small nerve fiber function in keloids: a controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:1002–1006

- Kassi K, Kouame K, Kouassi A, et al. Quality of life in black African patients with keloid scars. Dermatol Reports. 2020;12(2):8312.

- Murray JC. Keloids and hypertrophic scars. Clin Dermatol. 1994;12:27–37.

- Muneuchi G, Suzuki S, Onodera M, et al. Long-term outcome of intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide for the treatment of keloid scars in Asian patients. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2006; 40(2):111–116.

- Mustoe TA, Cooter RD, Gold MH, et al. International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:560–571.

- Mankowski P, Kanevsky J, Tomlinson J, et al. Optimizing radiotherapy for keloids: a meta-analysis systematic review comparing recurrence rates between different radiation modalities. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(4): 403–411.

- Alster TS, Handrick C. Laser treatment of hypertrophic scars, keloids, and striae. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:287–292.

- Karsai S, Roos S, Hammes S, et al. Pulsed dye laser: what’s new in non-vascular lesions? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007; 21(7):877–890.

- Chan HH, Wong DSY, Ho WS, et al. The use of pulsed dye laser for the prevention and treatment of hypertrophic scars in Chinese persons. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:987–94.

- Rossi A, Lu R, Frey MK, et al. The use of the 300 microsecond 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of keloids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(11):1256–1262.

- Al-Mohamady Ael-S, Ibrahim SM, Muhammad MM. Pulsed dye laser versus long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of hypertrophic scars and keloid: a comparative randomized split-scar trial. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016 Aug;18(4):208-12.