J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(9 Suppl 1):S19–S23

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(9 Suppl 1):S19–S23

by Debatri Datta, MD; Rashmi Sarkar, MD, MNAMS;and Indrashis Podder, MD, DNB

Dr. Datta is a consultant dermatologist at Oliva Skin Clinic, in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Dr. Sarkar is with the Department of Dermatology, LHMC and associated KSCH and SSK Hospital in New Delhi, India. Dr. Podder is with the Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine and Sagore Dutta Hospital in Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for the preparation of this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Chronic dermatoses, such as atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, and psoriasis, can affect children. Apart from impacting the pediatric patient’s quality of life, these disorders can also have a profound impact on the quality of life of their parents or closest caregivers and other family members. In an effort to better understand the relationship between parental stress and chronic dermatoses in children, we reviewed the available literature, which is scarce. Data indicate that the negative impact that chronic dermasoses in children can have on their parents is often overlooked during dermatologic consultation. Increased parental/caregiver stress can contribute to poor psychological adjustment of the parent to the child, potentially leading to a decreased level of childcare. Financial burden caused by prolonged therapy may further impact the parental care of the child. We as healthcare professionals should address parental and caregiver stress and incorporate appropriate measures to ensure optimal care of children with chronic dermatoses.

KEYWORDS: Chronic childhood dermatoses, parental, caregiver, stress, quality of life

Chronic childhood dermatoses, such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, icthyosis, vitiligo, urticaria, and acne vulgaris, can require frequent dermatologic consultations and have a profound impact on a pediatric patient’s quality of life.1 Demand for social and psychological support increases as these children grow up and integrate into society, and children with severe disease may need around-the-clock care for years. Studies have shown that parents caring for children with chronic disorders often experience negative changes in psychosocial status, which can negatively impact adherence to treatment for the child, resulting in worsening of the condition.1–3

Although research exists for chronic systemic illnesses, such as epilepsy, asthma, cancer, and diabetes, to our knowledge, literature is scarce regarding the effect that caring for a child with a chronic dermatosis can have on the parent.2 Here we explore the existing literature to better understand the impact that caring for a child with a chronic dermatosis can have on the parent/caregiver’s mental health (e.g., stress) and quality of life.

Materials and Methods

We undertook a comprehensive English literature search across multiple databases including PubMed (MEDLINE database), Scopus, and Cochrane using the keywords (alone and in combination) and MeSH items “chronic childhood dermatoses” OR “atopic dermatitis” OR “vitiligo” OR “psoriasis” OR “acne” OR “urticaria,” AND “parental stress” OR “caregiver stress” OR “parent quality of life” OR “caregiver quality of life” OR “family quality of life” to obtain relevant articles, priority being given to prospective, randomized, controlled trials and those concerning chronic dermatological disorders and parental or caregiver stress. Additional data were obtained from the reference lists of selected articles.

Results

Overall we obtained three review articles (1 foused on atopic dermatitis) and 20 clinical studies (5: atopic dermatitis, 4: vitiligo, 4: psoriasis, 1: psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, 1: epidermolysis bullosa, 5: chronic childhood dermatoses, 1: alopecia areata). We analyzed these articles and prepared the current manuscript along with a relevant review of literature.

Discussion

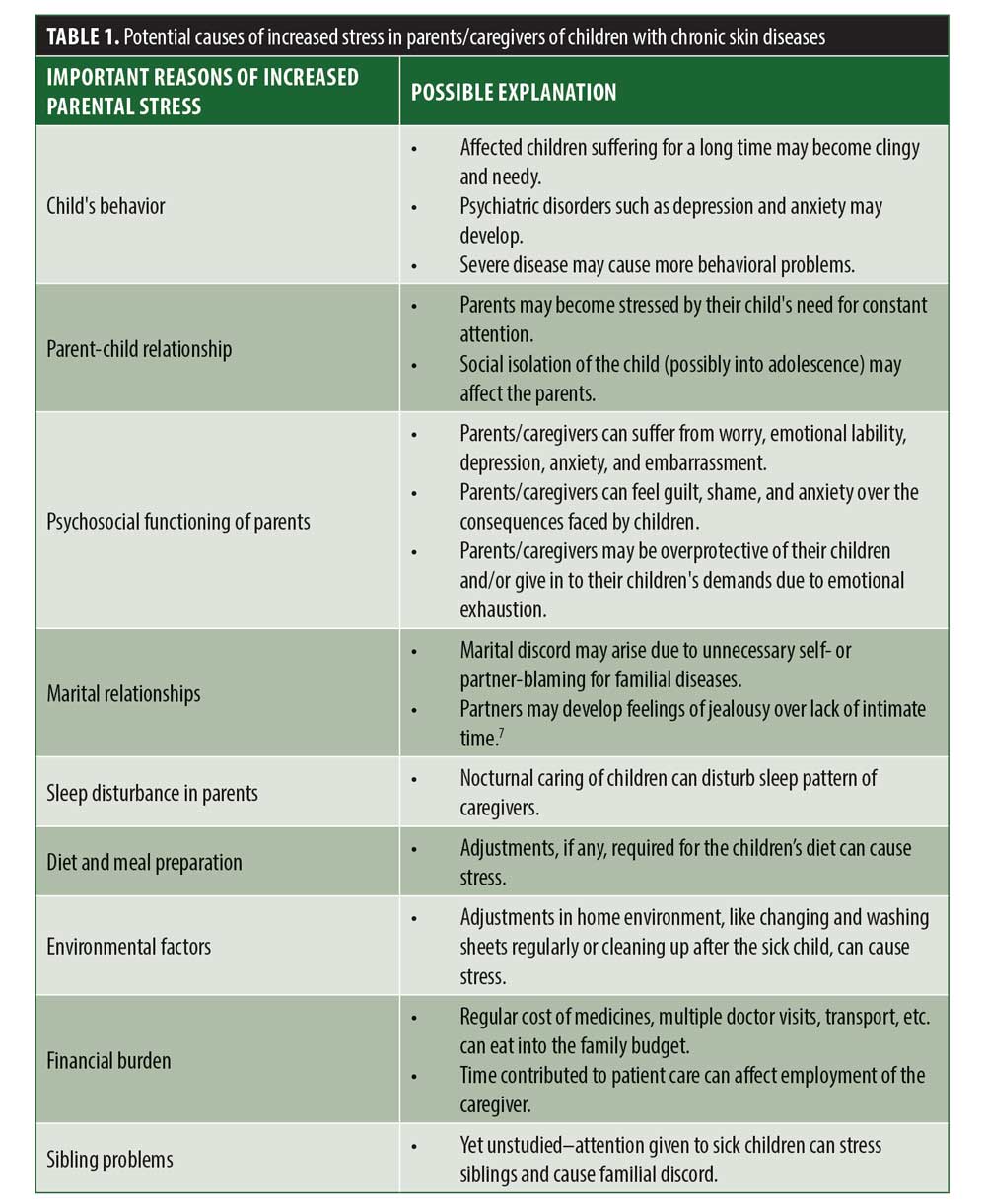

Although there have been several studies concerning parental stress in chronic childhood morbidities, such as bronchial asthma, cancer, epilepsy, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and sickle cell anaemia,2 data specifially on chronic dermatoses are scarce. Among the available relevant literature, the majority of the articles we found pertained to childhood atopic dermatitis, followed by psoriasis.1–3 Our analysis of the available data revealed that chronic childhood dermatoses can affect the parental/caregiver’s quality of life and induce stress for several possible reasons, which are highlighted in Table 1.4–10

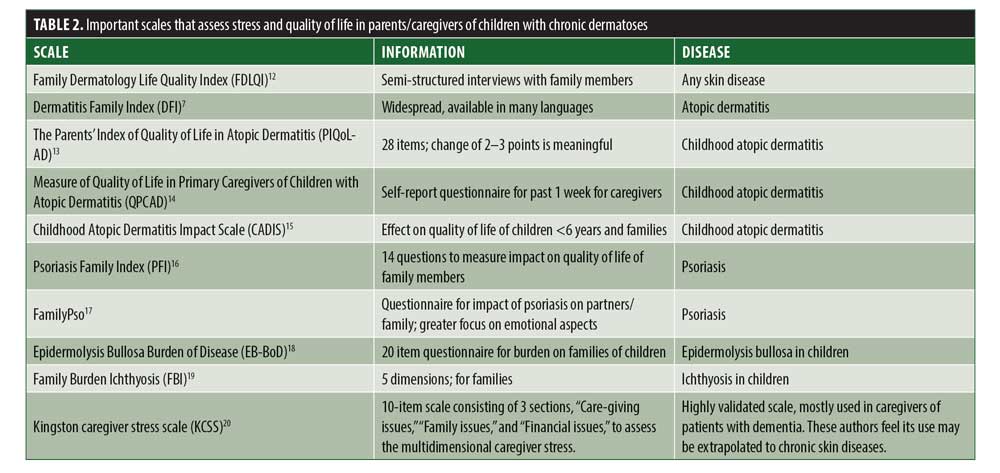

Scales to assess parental/caregiver stress. A vital problem in assessing parent/caregiver stress is the paucity of scales to document its presence and severity. Such documentation is necessary, not only for academic purposes, but also to assess the role of therapy in such individuals. Over the years, several scales and instruments have been designed to measure the impact of dermatological diseases on families and caregivers (Table 2).7,11–20

Atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis is one of the most studied childhood dermatoses in relation to familial stress. A study of American children with atopic dermatitis reported that parents experienced self-blame and guilt on observing their children suffer.5 As the disease persisted into adolescent years, resultant social isolation of the child often prolonged and aggravated parental stress.5 In a Chinese study,21 mothers spent more time with their children with atopic eczema, compared to other caregivers, and reported more suffering (i.e., negative effects on mental and physical well-being due to difficulty in simultaneously managing childcare responsibilities with other household responsibilities.5 Another study reported that mothers caring for children with atopic dermatitis were more anxious and depressed, compared to controls.22 However, educational interventions and behavioural modifications have been shown to reduce the severity of disease in the child and help both child and parent/caregiver improve psychologically.23

A study using the Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index (IDQOL) and Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI) to measure the quality of life in families with children with atopic dermatitis noted tiredness and sleep deprivation in parents/caregivers due to the children taking a long time to fall asleep.24 In a study by Sarkar et al,25 researchers reported increased stress and submissive personality traits in mothers of Indian children with atopic dermatitis, which appeared to increase psychological disturbances in their children. In addition to emotional stress, the need for cleanliness to avoid environmental allergens, as well as the imposed financial burden as a result of long-term treatment and care, were reported to further increase stress in parents and caregivers of such children.25

Vitiligo. Vitiligo is an acquired depigmenting disease that destroys melanocytes, affecting one or multiple regions of the body.26 Childhood vitiligo is common—50 percent of vitiligo patients note onset before 20 years of age, amd 25 percent have onset before the age of 10. There is female preponderance for vitiligo and segmental distribution (i.e., distributed along a dermatome).26 Though vitiligo does not cause physical limitations, the cosmetic disfigurement can result in social discrimination and ostracization of the child, which can negatively impact the psychosocial status of the child, the child’s parent/caregiver, and other members of the child’s family.

Studies in children and adolescents with vitiligo have assessed its impact on patient quality of life, and greater incidence of childhood depression has been reported.27,28 Interestingly, the decreased quality of life appeared to be dependent on the patient’s apprehensions and psychosocial adjustments, rather than actual clinical severity.29 However, very few studies are available regarding stress of parents, caregivers, and families in regard to their children with vitiligo.

A study by Amer et al included 50 children with vitiligo and their parents and 50 healthy controls.30 The Self-rated Health Measurement Scale (SRHMS) and the Dermatitis Family Impact Questionnaire (DFI) were used to assess the impact of vitiligo on the life of the patients and their families. Investigators reported greater psychological distress and feelings of embarrassment among parents of patients with vitiligo. Parents of children with generalized, progressive disease were more severely affected. The mothers were more affected than fathers, reporting exhaustion, self-blame, and disappointment regarding disease prognosis.30

A Brazilian study assessing anxiety and depression in caregivers of pediatric dermatology patients noted anxiety and depression in 42 percent and 26 percent of participants, respectively.31 The extent of visible body surface area affected correlated with degree of anxiety in caregivers. An Indian study noted parents of children with vitiligo reported being worried about the children developing low self-esteem and difficulty in arranging marriages for them.32 This parental anxiety was reported to conversely affect the children psychologically, in that the children became concerned over their parents distress. Another hospital-based Indian study on immediate caregivers (parents and grandparents) of pediatric patients with vitiligo, using the Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI), detected emotional distress in caregivers and impaired quality of life in female patients and those with longer duration of disease. The researchers recommended psychiatric counseling for the patient and family members.33

Psoriasis. Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease, of which adolescents comprise nearly one-third of the cases. Childhood psoriasis commonly manifests as plaque psoriasis, though the plaques may be smaller, thinner, and less scaly than those in adults, making diagnosis difficult.34 As with vitiligo, the unusual appearance of the skin can cause mental stress in the patients and their families; the associated pruritus and joint manifestations can cause physical stress as well. Studies have been conducted in adult patients with psoriasis and their family members, which depict a drop in quality of life and difficulty in attending to daily chores.34–40 Few studies are available regarding the impact of psoriasis on caregivers of pediatric patients.

A 2007 study noted the impact of psoriasis on the lives of children, adolescents, and their family members using the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI), Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI), Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC).37 The researchers noted low scores on the life quality indices for caregivers of patients, even if the disease was considered mild in severity. A Swedish study using the Dermatitis Family Impact scale also showed emotional distress and financial burden on the caregivers of pediatric patients with psoriasis.34 Another study that interviewed parents of pediatric patients with psoriasis indicated damaged emotional milieu in the parents, including sadness, depression, and anxiety over their child’s condition, as well as social isolation, sleep deprivation, neglect in personal care, and worry over finances and time management.39 Finally, a review in 2019 reported that parents indicated their children’s disease (psoriasis) affected their own quality of life, causing stress, depression, and frustration.40

Other chronic dermatoses. Questionnaires and scales have been designed to assess impact on family members of pediatric patients with other skin disorders, such as epidermolysis bullosa (Epidermolysis Bullosa Burden of Disease[EB-BoD])18 and ichthyoses (Family Burden Ichthyosis [FBI]).19 A survey of patients with epidermolysis bullosa and their caregivers and families noted a considerable burden on the family by hampering education, family life, and financial status.41 In 2019, Naik et al42 reported increased stress on parents and family members of children with erythropoietic protoporphyria. Rodgers43 implicated the stress of family members and caregivers as an important risk factor in alopecia areata.

We were unable to find any studies regarding parental/caregiver stress in acne or urticaria, two common dermatological diseases affecting children and adolescents.

Therapeutic Implications

Basra and colleagues suggested that including the parents/caregivers of patients with childhood dermatoses in the overall treatment plan helped decrease feelings of mental distress, lack of control, and helplessness.6 Thus, psychological counseling and in-depth education regarding patient care is necessary for such parents and caregivers. Proper explanation regarding prognosis of disease might help the parents cope with stress better and plan future activities as appropriate. Several support groups have been established for specific diseases to educate and counsel parents and caregivers. This social support often proves invaluable in maintaining the mental strength of parents and caregivers. Psychiatrist and psychologist referrals for further specialized treatments, such as behavioral therapy and/or pharmacotherapy, should be considered for those not responding to counseling alone. Clinicians should focus attention not only on the children with dermatological disorders, but also their parents/ caregivers, for a more holistic and inclusive treatment approach.

Conclusion

Parental/caregiver stress is an area of concern when treating pediatric patients with chronic dermatoses. The parents/caregivers of these children can suffer from anxiety, worry, guilt, and possible social exclusion. Their children’s constant need for care and visits to doctors also decreases the parents’/caregivers’ quality of life and affects their interrelationships. The added financial burden of their child’s medical care can also negatively impact parents/caregivers. Parental/caregiver stress, in turn, potentially could negatively impact the care they provide their children, which might result in worsening of the child’s dermatological disease. We recommend including the parents/caregivers and other members of the family in the treatment plan of the child and integrating an interdisciplinary treatment approach that includes referral to psychological therapy for both child and parent to optimize patient outcomes. This article is intended to increase awareness among dermatologists about the potential stress that may develop in parents/caregivers of children with chronic childhood dermatoses, an aspect often overlooked as evidenced by paucity of literature. Further large-scale studies are needed to address this subject and explore mitigating options.

References

- De Maeseneer H, Van Gysel D, De Schepper S, et al. Care for children with severe chronic skin diseases. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178(7):1095–1103.

- Cousino MK, Hazen RA. Parenting stress among caregivers of children with chronic illness: a systematic review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(8):809–828.

- Streisand R, Braniecki S, Tercyak KP, Kazak AE. Childhood illness-related parenting stress: the Pediatric Inventory for Parents. J Pediatr Pscyhol. 2001;26(3):155–162.

- Yang EJ, Beck KM, Sekhon S, et al. The impact of pediatric atopic dermatitis on families: a review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(1):66–71.

- Chamlin SL, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Chren MM. Effects of atopic dermatitis on young American children and their families. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):607–611

- Basra MKA, Finlay AY. The family impact of skin diseases: the greater patient concept. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(5):929–937.

- Lawson V, Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, et al. The family impact of childhood atopic dermatitis: the Dermatitis Family Impact Questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138(1):107–113

- Bridgman AC, Eshtiaghi P, Cresswell-Melville A, et al. The burden of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in Canadian children: a cross-sectional survey. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(4):443–444

- Ricci G, Bendandi B, Pagliara L, et al. Atopic dermatitis in Italian children: evaluation of its economic impact. J Pediatr Health Care. 2006(50);20:311–315

- Knecht C, Hellmers C, Metzing S. The perspective of siblings of children with chronic illness: a literature review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(1):102–116

- Sampogna F, Finlay AY, Salek SS, et al. Measuring the impact of dermatological conditions on family and caregivers: a review of dermatology-specific instruments. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(9):1429–1439.

- Basra MK, Edmunds O, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Measurement of family impact of skin disease: further validation of the Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(7):813–821.

- 14a McKenna SP, Whalley D, Dewar AL, et al. International development of the Parents’ Index of Quality of Life in Atopic Dermatitis (PIQoL-AD). Qual Life Res. 2005;14(1):231–241.

- Kondo-Endo K, Ohashi Y, Nakagawa H, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire measuring quality of life in primary caregivers of children with atopic dermatitis (QPCAD). Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(3):617–625.

- Chamlin SL, Cella D, Frieden IJ, et al. Development of the Childhood Atopic Dermatitis Impact Scale: initial validation of a quality-of-life measure for young children with atopic dermatitis and their families. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(6):1106–1111.

- Eghlileb AM, Basra MKA, FInlay AY. The Psoriasis Family Index: preliminary results of validation of a quality of life instrument for family members of patients with psoriasis. Dermatology. 2009;219(1):63-70.

- Mrowietz U, Hartmann A, Weissmann W, Zschocke I. FamilyPso–a new questionnaire to assess the impact of psoriasis on partners and family of patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(1):127–134.

- Dufresne H, Hadj-Rabia S, Taieb C, Bodemer C. Development and validation of an epidermolysis bullosa family/parental burden score. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(6):1405–1410.

- Dufresne H, Hadj-Rabia S, Meni C, et al. Family burden ininherited ichthyosis: creation of a specific questionnaire. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:28.

- Sadak T, Korpak A, Wright JD, Lee MK, Noel M, Buckwalter K, Borson S. Psychometric evaluation of Kingston Caregiver Stress Scale. Clinical Gerontologist. 2017;40:268-80.

- Cheung WKH, Lee RLT. Children and adolescents living with atopic eczema: An interpretive phenomenological study with Chinese mothers. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:2247-2255.

- Pauli-Pott U, Darui A, Beckmann D. Infants with atopic dermatitis: maternal hopelessness, child-rearing attitudes and perceived infant temperament. Psychother Psychosom. 1999;68(1):39–45.

- Klinnert MD, Booster G, Copeland M, et al. Role of behavioral health in management of pediatric atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(1):42–48.

- Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. An audit of the impact of a consultation with a paediatric dermatology team on quality of life in infants with atopic eczema and their families: further validation of the Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index and Dermatitis Family Impact score. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(6):1249–1255.

- Sarkar R, Raj L, Kaur H, et al. Psychological disturbances in Indian children with atopic eczema. J Dermatol. 2004;31(6):448–454.

- Nordlund J. Vitiligo: a review of some facts lesser known about depigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56(2):180–189.

- Inamadar A, Palit A. Childhood vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78(1):30–41.

- Bilgiç O, Bilgiç A, Akis HK, et al. Depression, anxiety and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36(4):360–365.

- Choi S, Kim DY, Whang SH, et al. Quality of life and psychological adaptation of Korean adolescents with vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(5):524–529.

- Amer AAA, McHepange UO, Gao XH, et al. Hidden victims of childhood vitiligo: impact on parents’ mental health and quality of life. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(3):322–325.

- Manzoni AP, Weber MB, Nagatomi AR, et al. Assessing depression and anxiety in the caregivers of pediatric patients with chronic skin disorders. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6):894–899.

- Ramam M, Pahwa P, Mehta M, et al. The psychosocial impact of vitiligo in Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(5):679–685.

- Gahalaut P, Chauhan S, Shekhar A, et al. Effect of occurrence of vitiligo in children over quality of life of their families: a hospital-based study using Family Dermatology Life Quality Index. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2018;19:21–25.

- Gånemo A, Wahlgren CF, Svensson Å. Quality of life and clinical features in Swedish children with psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28(4):375–379.

- Handjani F, Kalafi A. Impact of dermatological diseases on family members of the patients using Family Dermatology Life Quality Index: a preliminary study in Iran. Iran J Dermatol. 2013;16(4):128–131

- Leino M, Mustonen A, Mattila K, et al. Influence of psoriasis on household chores and time spent on skin care at home: a questionnaire study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5(2):107–116.

- Eghlileb AM, Davies EEG, Finlay AY. Psoriasis has a major secondary impact on the lives of family members and partners. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(6):1245–1250.

- Salman A, Yucelten AD, Sarac E, et al. Impact of psoriasis in the quality of life of children, adolescents and their families: a cross-sectional study. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(6):819–823.

- Tollefson MM, Finnie DM, Schoch JJ, Eton DT. Impact of childhood psoriasis on parents of affected children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):286–289.

- Na CH, Chung J, Simpson EL. Quality of life and disease impact of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis on children and their families. Children (Basel). 2019;6(12):133.

- Bruckner AL, Losow M, Wisk J, et al. The challenges of living with and managing epidermolysis bullosa: insights from patients and caregivers. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):1.

- Naik H, Shenbagam S, Go AM, Balwani M. Psychosocial issues in erythropoietic protoporphyria– the perspective of parents, children, and young adults: a qualitative study. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;128(3):314–319.

- Rodgers AR. Why finding a treatment for alopecia areata is important: a multifaceted perspective. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2018;19(1):S51–S53.