J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2023;16(8 Suppl 1):S12–S17

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2023;16(8 Suppl 1):S12–S17

Neal Bhatia, MD; Adelaide A. Hebert, MD; and James Q. Del Rosso, DO

Dr. Bhatia is with Therapeutics Clinical Research in San Diego, California. Dr. Hebert is with UTHealth McGovern Medical School in Houston, Texas. Dr. Del Rosso is with JDR Dermatology Research and Thomas Dermatology in Las Vegas, Nevada, and Clinical Research at Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery in Maitland, Florida.

Funding: Funding for this article was provided by Verrica Pharmaceutical in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Hebert has received research grants (paid to UTHealth McGovern Medical School) from Verrica, Pfizer, Arcutis, GSK, Ortho Dermatologics, and Galderma, and has received honoraria from Verrica, Pfizer, Galderma, Arcutis, Vine, Almirall, Bristol Myres Squibb, Leo, Vyne, Aslan DSMB: Ortho Dermatologics, GSK, and Sanofi Regeneron. Dr. Del Rosso is a consultant/advisor and investigator for Verrica Pharmaceutical.

ABSTRACT: Despite its high global prevalence, molluscum contagiosum (MC) is not well understood outside of dermatology. Due to the potential self-limiting nature of MC, a common clinical approach in management is to wait for the papules to resolve spontaneously over several weeks to months, without medical intervention. However, this “watch and wait” approach increases risk of spreading the virus to others, extending the duration of the infection, and emergence of several psychosocial issues (e.g., anxiety, embarrassment, isolation). Molluscum contagiosum can be particularly challenging to treat in immunocompromised patients (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], organ transplant recipients). This article reviews diagnostic characteristics and treatment options for MC, as well as associated risk factors and comorbidities. Treatment of immunocompromised individuals, in whom the risks of diffuse MC with persistence and spread are relatively high, is emphasized. The authors highlight the importance of actively treating the MC papules, as opposed to letting the virus “run its course” with no active intervention, with the goals of reducing the risk of spreading infection to others, shortening the duration of infection, and decreasing adverse psychosocial sequelae commonly associated with MC.

Introduction

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is an infection caused by a benign, double-strand DNA virus of the Poxviridae family. This infection manifests as 2- to 5-mm, rounded, pink- or skin-colored, smooth-surfaced, umbilicated papules that can occur individually or in clusters (Figure 1).1–6 The virus is spread through nonsexual or sexual direct contact with infected skin or shared objects (e.g., bath towels, swimming pools) or by autoinoculation. A meta-analysis reported a worldwide prevalence of just over eight percent and a higher rate of occurrence in geographical areas with warm climates.5 According to a thorough literature review, MC is most often seen in children 2 to 5 years of age, though the infection is also seen in sexually active adolescents and adults with normal immune systems and in immunocompromised individuals of all ages.6 Individuals with compromised immune systems appear to be at elevated risk for MC infection with atypical appearing lesions and/or more extensive involvement, ; reported prevalence rates are approximately 20% in HIV patients, 7% in organ transplant recipients, and 0.5% in pediatric cancer patients.7–12 While MC is known to be self-limiting over months to years in those with competent immune systems, there is no evidence of spontaneous resolution of MC in patients with HIV, underscoring the importance of actively treating MC in this patient population.7

This article reviews diagnostic methods and available treatment options for MC, with an emphasis on risk factors and comorbidities. A summary discussion of a pharmaceutical-grade topical cantharidin formulated as a drug-device combination (YCANTH™, Verrica Pharmaceuticals, West Chester, Pennsylvania) is included; this product is the first treatment for MC specifically approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

A primary goal of this review is to increase awareness among dermatologists and other healthcare professionals of the importance of actively treating MC in all presenting patients, especially those with compromised immune systems, versus letting the virus “run its course” with no active intervention.

Diagnostic Considerations

MC presenting with its distinctive morphologic characteristics of the lesions is, typically, a straightforward clinical diagnosis. Most MC lesions are smooth, small, well-defined, skin-colored or light pink papules with central umbilication. A dermatoscope may be used to better identify the characteristic features of an MC papule in cases where the individual lesions are very small in size. Occasionally, a biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis, especially in immunocompromised patients presenting with atypical-appearing lesions.2,6,13 Enzyme-linked immunoassays (ELISA) testing for MC is used in research studies but is not commonly utilized in real-world clinical practice.14,15

It is important to note that MC papules can resemble verruca plana (flat warts), especially early in the course of infection when the papules are small, flat, and pale in color, as opposed to their usual domed appearance—clinicians are encouraged to be thorough in their assessments, to avoid misdiagnosis and delaying appropriate treatment. Cutaneous lesions of disseminated Cryptococcus neoformans infection can also simulate MC clinically; thus, in immunosuppressed patients (e.g., those with human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]), biopsy is prudent for diagnostic confirmation.13

The possibility of sexual abuse in pediatric cases of MC is important to consider, especially when the lesions only appear in the anogenital region.16–18 If the clinician feels uncertain of the possibility of child abuse, the primary care physician should be consulted. In a case series of 157 pediatric patients who were referred to a sexual abuse clinic due to anogenital signs and symptoms, 75 percent of the referrals came from medical clinics; of this patient subpopulation, 15 percent were considered to be probable or definite victims of sexual abuse.19 MC and child abuse are both global problems and have been reported in many cultures; thus, clinicians who treat children will likely encounter, over the course of their careers, pediatric cases of MC involving the anogenital region.20 It important for clinicians and their staff to develop a practical and structured approach to handling the consideration of sexual abuse in these children. While Western nations tend to be more open to approaching, reporting, and managing child abuse, discussing this subject might be considered “taboo” in other parts of the world or within certain cultural communities in the US, which can potentially impede evaluation and appropriate care.20,21

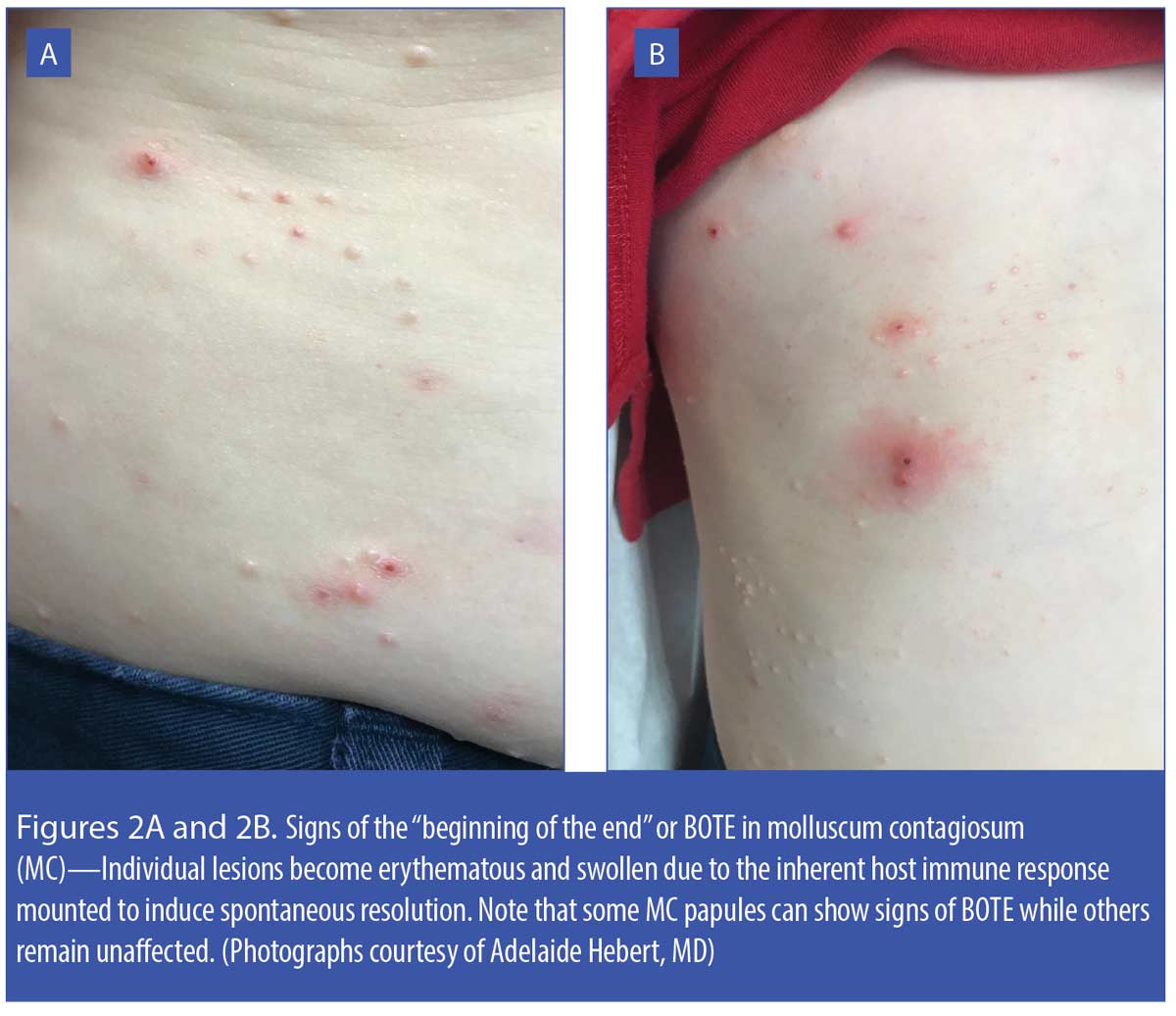

When an MC papule begins to regress spontaneously, a clinical phenomenon called “beginning of the end” (BOTE sign) is initiated, in which the individual MC papules develop erythema, edema, and sometimes crusting. The BOTE sign is commonly seen in children with MC and can appear in some MC lesions while others remain unaffected (Figures 2A and 2B). Parents/caretakers might perceive BOTE signs to be indicative of bacterial infection and wish to self-treat with a topical antimicrobial agent or request antibiotic therapy from their physicians; however, the BOTE sign is not a sign of bacterial infection; rather, it is believed to reflect mobilization of the host immune response that induces spontaneous resolution of the affected MC papules.22

Another clinical phenomenon, molluscum dermatitis, is observed in around 10 percent of children with MC. Molluscum dermatitis, presenting as an eczematous-appearing eruption usually in the general anatomic region being affected by MC, has been described as an “id reaction” secondary to an immunologic response to the MC virus (Figure 3).23–25 Some research suggests treating molluscum dermatitis with an emollient; if markedly pruritic, a short course (3–5 days) of low-to-medium potency topical corticosteroid therapy has also been recommended.23,24

MC is a frequent comorbidity in patients with atopic skin, with concurrent presence of both MC lesions and actively flared atopic dermatitis in some patients.25–27 As shown in Figure 4, MC papules may be masked on cursory inspection due to the extent of inflammation present from both the eczematous dermatitis and secondary infection. Secondary bacterial infection in patients with atopic dermatitis is usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus, which is frequently found in both lesional and non-lesional atopic skin.28

Evaluation and Management Principles

Importance of active treatment. There are multiple treatment approaches to managing MC that have been described in the literature.29 However, because MC might resolve spontaneously over time without therapeutic intervention, many clinicians report taking a noninterventional approach or “benign neglect”—that is, leaving the MC infection to run its natural course without treatment.1,5,30 A cross-sectional survey of 2,000 healthcare professionals that included primary care physicians, pediatricians, obstetrician-gynecologists, dermatologists, nurse practitioners, and registered dietitians evaluated clinician knowledge, attitudes, and practice related to treatment of MC.1 The survey results revealed that 41.6 percent of the respondents would recommend benign neglect over active treatment of MC to their patients (e.g., “Don’t be concerned—this will go away.”)1

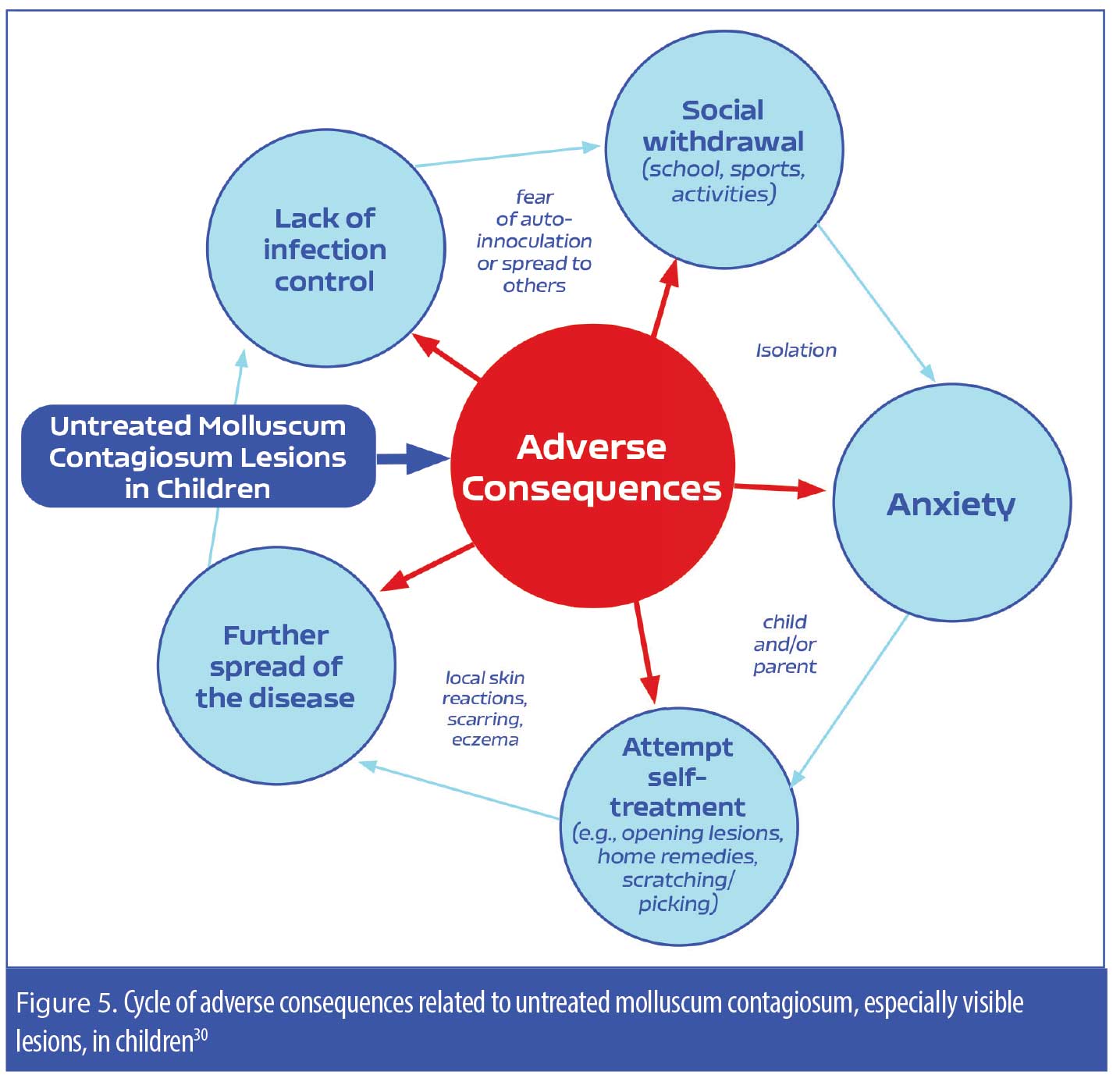

While the benign neglect approach to treating MC might appeal to patients with MC, especially the parents/caretakers of children with MC, what is often lost in its explanation is that MC can potentially persist for several months to years in many individuals, can be spread to others who are in close personal contact with the patient, and can lead to “real world” psychosocial issues in the patient (e.g., feelings of embarrassment and/or fear of transmitting the virus to others, anxiety, social isolation).5 A study evaluating pediatric patients with MC (N=306; age range 4–14 years of age) reported that, when left untreated, the MC infection frequently persisted for more prolonged periods of time and had higher rates of transmission to others in the household.30 Additionally, the pain and pruritus associated with MC can also negatively impact a pediatric patient’s quality of life, which further underscores the importance of taking an active approach to treatment of MC and should be factored in the clinician-patient/parent decision-making process (Figure 5, Table 1).1–5,30

Initial assessment and consultation. When treating patients with MC, the initial assessment should involve a thorough clinical examination to determine the extent, location(s), and number of lesions.31 Appropriate history should be taken to identify potential sources of the infection, as well as the patient’s immune status and response to previous treatments, if any. Special patient considerations to factor into the treatment decision-making process include active involvement in sports or other close-contact physical activities, which may warrant a more rapid resolution of the condition to avoid spreading the infection to others; pregnancy, which may limit the treatment options to curettage, cryotherapy, or laser therapy; and anogenital lesions in adults, which may signify the presence of other sexually transmitted diseases.31,32

Clinicians are encouraged to be thorough when discussing treatment options of MC with their patients or patient caregivers, including educating them on the lack of cure, the potential need for repeated courses of therapy, and the potential adverse effects of individual treatment options. Shared decision-making between the patient or patient’s caregiver and the clinician is an optimal approach.33

Treatment options. There are numerous treatment options for MC, which are thoroughly reviewed elsewhere29,34 as well as in more detail in the article, “Molluscum Contagiosum: Epidemiology, Treatment Options, and Therapeutic Gaps,” on pages S4–S11 of this supplement. Topical application of cantharidin is a commonly used clinician-directed treatment that is supported by a thorough literature review on its use in MC and verrucae.35,36 Until recently, however, topical cantharidin was only available as a compounded formulation, and the potential inconsistency among the different formulation sources and lack of standardized application techniques have led to variabilities in its efficacy and safety.37 Additionally, there was a lack of well-controlled studies that evaluated recommended application methods (to avoid excess application to surrounding skin), frequency of use, and appropriate wash-off time, which further added to the potential inconsistency and variability of outcomes with topical cantharidin. Recently, however, the FDA approved a pharmaceutical-grade, ether-free, topical cantharidin 0.7% solution prepared as a combined drug-device product (YCANTH™, Verrica Pharmaceuticals, West Chester, Pennsylvania), which now provides clinicians with an evidence-based, standardized formulation of topical cantharidin that can be delivered with specified dosing recommendations and application technique to individual MC lesions. The device allows for more precise application to individual MC lesions while limiting exposure to surrounding non-lesional skin.

Risk Factors and Comorbidities That Impact MC Management

Molluscum dermatitis. As discussed previously, molluscum dermatitis, considered an id reaction-type clinical phenomenon, is an eczematous-appearing eruption usually in the general anatomic region being affected by MC.

Atopic dermatitis. The multiple innate epidermal barrier dysfunctions associated with atopic skin predispose patients with atopic dermatitis to microbial infections, such as MC.25–27,38 Pruritus caused by eczematous dermatitis can lead to scratching, which can further exacerbate the cycle of barrier dysfunction and cutaneous infection.34 As the MC lesions resolve, the associated eczematous dermatitis will often subside spontaneously. A history of eczematous dermatitis, especially atopic dermatitis, appears to increase the risk of contracting MC. In an Australian study, researchers reported that 62 percent of children with MC had a history of eczema.39

Skin of color. While MC occurs in people of all races, ethnicities, and nationalities, data are limited regarding disease epidemiology and treatment considerations among the different ethnic groups. Sequelae after various treatments can differ depending on inherent skin color. For example, treatment of lesions using pulsed-dye laser therapy can cause skin of color to temporarily develop lighter or darker foci of dyschromia where the laser treatment occurred; this typically resolves in 6 to 24 weeks.40 Additional research is needed to better understand the epidemiology, disease course, and response to treatment among different ethnicities, races, and skin colors.

Compromised immune system. MC was first observed as a comorbidity of HIV in 1983, and the prevalence of MC in this patient population could be as high as 20 percent.8 Research indicates that the presence of MC in patients with HIV may be a sign of HIV progression.8,9,11 In a study of 456 patients with an HIV-associated skin disorder, nearly nine percent had MC.9 Large lesions up to 1cm in diameter were observed in some individuals, and multiple lesions in atypical locations, such as diffuse involvement of the face, were common among this patient population. The researchers concluded that MC is relatively common in patients with HIV and is associated with worsened mortality. Though the researchers did not consider MC to be an independent prognostic marker, they did conclude that MC could potentially serve as a clinical marker for advanced HIV progression (Figure 5).9

Iatrogenic immunosuppression that occurs in patients who have undergone organ transplantation also increases a patient’s risk of contracting MC, which can be recalcitrant to treatment and atypical in presentation among this patient population. In a review of 145 pediatric patients who underwent organ transplants, seven percent contracted MC, all of whom were resistant to treatment.41 Research suggests that patients whose immune systems have been weakened by chemotherapy, biologic treatment, or systemic corticosteroid treatment might also be more susceptible to MC.42,43 Further research is needed in this area.

Anogenital lesions. MC in young immunocompetent adults is most often contracted through sexual contact and thus frequently affects the anogenital region.34 In otherwise healthy adults with anogenital MC, education should be provided regarding the infectious nature of the lesions and the importance of abstaining from sexual contact until the lesions are effectively treated.44 There is no single optimal treatment for anogenital MC—the treatment choices should be individualized based on the number, location, and extent of the lesions and patient preference.

Conclusion

The prevailing notion that MC should be left alone to run its course could be due to the prior absence of an FDA-approved treatment option, the lack of a universally recognized first-line treatment, and the practical difficulties of treating multiple lesions, especially in young children. Some underlying health conditions may increase the risk of contracting MC and contribute to intraindividual spread of lesions . Immunosuppression predisposes patients to emergence of multiple MC lesions, which are often more difficult to treat effectively and may be atypical in appearance. There is now strong consensus among the experts that benign neglect is not a recommended treatment approach in the majority of cases of MC. A number of treatment options are available, including physical modalities and topical therapies, the latter of which includes both clinician- and patient/caregiver-administered options. The availability of the first FDA-approved MC treatment is a drug-device product that allows a healthcare professional to apply pharmaceutical-grade topical cantharidin 0.7% solution to MC lesions in a directed fashion, the use of which is supported by randomized, controlled, pivotal trials establishing both efficacy and safety.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge LeQ Medical in Angleton, Texas, for their support in preparing this manuscript.

References

- Hughes C, Damon I, Reynods M. Understanding US healthcare providers’ practices and experiences with molluscum contagiosum. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e76948.

- Silverberg N. Pediatric molluscum: an update. Cutis. 2019;104(5):E1–E2.

- Mathes EF, Frieden IJ. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum with cantharidin: a practical approach. Pediatr Ann. 2010;39(3):124–128, 130.

- Serin Ş, Bozkurt Oflaz A, Karabağlı P, et al. Eyelid molluscum contagiosum lesions in two patients with unilateral chronic conjunctivitis. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2017;47(4):226–230.

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Piguet V, Francis NA. Epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31(2):130–136.

- Meza-Romero R, Navarrete-Dechent C, Downey C. Molluscum contagiosum: an update and review of new perspectives in etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:373–381.

- Kaufman WS, Ahn CS, Huang WW. Molluscum contagiosum in immunocompromised patients: AIDS presenting as molluscum contagiosum in a patient with psoriasis on biologic therapy. Cutis. 2018;101(2):136–140.

- Czelusta A, Yen-Moore A, Van der Straten M, et al. An overview of sexually transmitted diseases. Part III. Sexually transmitted diseases in HIV-infected patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(3):409–432; quiz 433–406.

- Husak R, Garbe C, Orfanos CE. [Mollusca contagiosa in HIV infection. Clinical manifestation, relation to immune status and prognostic value in 39 patients]. Hautarzt. 1997;48(2):103–109.

- Erickson C, Driscoll M, Gaspari A. Efficacy of intravenous cidofovir in the treatment of giant molluscum contagiosum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(6):652–654.

- Chen X, Anstey AV, Bugert JJ. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(10):877–888.

- Chen KW, Yang CF, Huang CT, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a patient with adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2011;155(3):286.

- Rico MJ, Penneys NS. Cutaneous cryptococcosis resembling molluscum contagiosum in a patient with AIDS. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121(7):901–902.

- Konya J, Thompson CH. Molluscum contagiosum virus: antibody responses in persons with clinical lesions and seroepidemiology in a representative Australian population. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(3):

701–704. - Konya J, Thompson CH, De Zwart-Steffe RT. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for measurement of IgG antibody to molluscum contagiosum virus and investigation of the serological relationship of the molecular types. J Virol Methods. 1992;40(2):

183–194. - Bargman H. Is genital molluscum contagiosum a cutaneous manifestation of sexual abuse in children? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(5 Pt 1):847–849.

- Bargman H. Genital molluscum contagiosum in children: evidence of sexual abuse? CMAJ. 1986;135(5):432–433.

- Williams TS, Callen JP, Owen LG. Vulvar disorders in the prepubertal female. Pediatr Ann. 1986;15(8):588–605.

- Kellogg ND, Parra JM, Menard S. Children with anogenital symptoms and signs referred for sexual abuse evaluations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(7):634–641.

- Bang GA, Tolefac P, Savom EP, et al. Anal/anogenital lesion revealing child sexual abuse: a case series of an unusual situation in a black African setting. Int J Surg Case Rep 2020;76:341–344.

- Ramabu NM. The extent of child sexual abuse in Botswana: hidden in plain sight. Heliyon. 2020;6(4):e03815.

- Leung A, Davies H. Molluscum contagiosum—an overview. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2012;8(4):346–349.

- Hussain SH, Treat JR, Yan AC. Infantile atopic dermatitis. In: Rudikoff D, Cohen SR, Scheinfeld N, (eds). Atopic Dermatitis and Eczematous Disorders. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group);2014:86.

- Netchiporouk E, Cohen BA. Recognizing and managing eczematous id reactions to molluscum contagiosum virus in children. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1072–e1075.

- Treadwell PA. Eczema and infection. Peditar Infect Dis J. 2008;27:551–552.

- Silverberg NA, Duran-McKinster C. Special considerations for therapy of pediatric atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:351–363.

- Hurwitz S. Viral diseases of the skin. In: Hurwitz S (ed). Clinical Pediatric Dermatology, 2nd Edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;1981:338–340.

- Leung DYM. Role of Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis. In: Bieber T, Leung DYM (eds). Atopic Dermatitis. New York: Marcell Dekker Inc.;2002:401–418.

- Javed A, Coulson I. Molluscum contagiosum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, Coulson I (eds). Treatment of Skin Disease, 4th Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier-Saunders; 2014;460–463.

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Finlay AY, et al. Time to resolution and effect on quality of life of molluscum contagiosum in children in the UK: a prospective community cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(2):190–195.

- Coyner T. Molluscum contagiosum: a review for healthcare providers. J Dermatol Nurse Assoc. 2020;12(3).

- Edwards S, Boffa MJ, Janier M, et al. 2020 European guideline on the management of genital molluscum contagiosum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(1):17–26.

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–1367.

- Nguyen HP, Franz E, Stiegel KR, et al. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum in adult, pediatric, and immunodeficient populations. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18(5):299–306.

- Torbeck R, Pan M, DeMoll E, Levitt J. Cantharidin: a comprehensive review of the clinical literature. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(6).

- Cherniack EP. Bugs as drugs, part 1: insects: the “new” alternative medicine for the 21st century? Altern Med Rev. 2010;15(2):124–135.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik L. Topical cantharidin in the management of molluscum contagiosum: preliminary assessment of an ether-free, pharmaceutical-grade formulation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(2):27–30.

- Silverberg NB, Sidbury R, Mancini AJ. Childhood molluscum contagiosum: experience with cantharidin therapy in 300 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(3):503–507.

- Braue A, Ross G, Varigos G, Kelly H. Epidemiology and impact of childhood molluscum contagiosum: a case series and critical review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(4):287–294.

- American Academy of Dermatology site. Molluscum contagiosum: diagnosis and treatment. 2021. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/a-z/molluscum-contagiosum-treatment. Accessed 2 May 2021.

- Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Cochat P, et al. Skin diseases in children with organ transplants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(6):932–939.

- Lim KS, Foo CC. Disseminated molluscum contagiosum in a patient with chronic plaque psoriasis taking methotrexate. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32(5):591–593.

- Bansal S, Relhan V, Roy E, et al. Disseminated molluscum contagiosum in a patient on methotrexate therapy for psoriasis. Ind J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80(2):179–180.

- Ting PT, Dytoc MT. Therapy of external anogenital warts and molluscum contagiosum: a literature review. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(1):68–101.