J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(4):32–35.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(4):32–35.

by Alexandra Edelman, MD; Timothy Brown, MD; Roopa Gandhi, MD; and Rishi Gandhi, MD

Drs. Edelman, Brown, and Rishi Gandhi are with the Division of Dermatology at the University of Louisville School of Medicine in Louisville, Kentucky. Dr. Roopa Gandhi is with the Gastroenterology Division of the Wright State University Department of Internal Medicine in Dayton, Ohio.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Anorectal melanoma is a rare and aggressive malignant neoplasm with an indolent course, manifesting with nonspecific symptoms and a poor prognosis. We present a case of anorectal melanoma that was initially treated as hemorrhoids and correctly diagnosed after lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. We also present the latest findings in the literature about anorectal melanomas and discuss updates about treatment options and management.

Key words: Melanoma, anorectal melanoma, mucosal melanoma

Anorectal melanoma is a rare and aggressive malignant neoplasm. It accounts for less than two percent of melanomas and it is the third most common location of melanoma, after the skin and retina.1–3 Unlike the generally favorable prognosis of early-stage cutaneous melanomas, the prognosis of anorectal melanoma is extremely poor, with a median survival of less than two years.1,4 This tumor has an indolent course and manifests with nonspecific symptoms, including rectal bleeding, changes in bowel habits, and pain or itching, resembling benign gastrointestinal disorders.1–5 We present a case of anorectal melanoma that was initially treated as hemorrhoids and correctly diagnosed after lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. We also present the latest findings in the literature about anorectal melanomas and discuss newer updates concerning treatment options and management.

Case Presentation

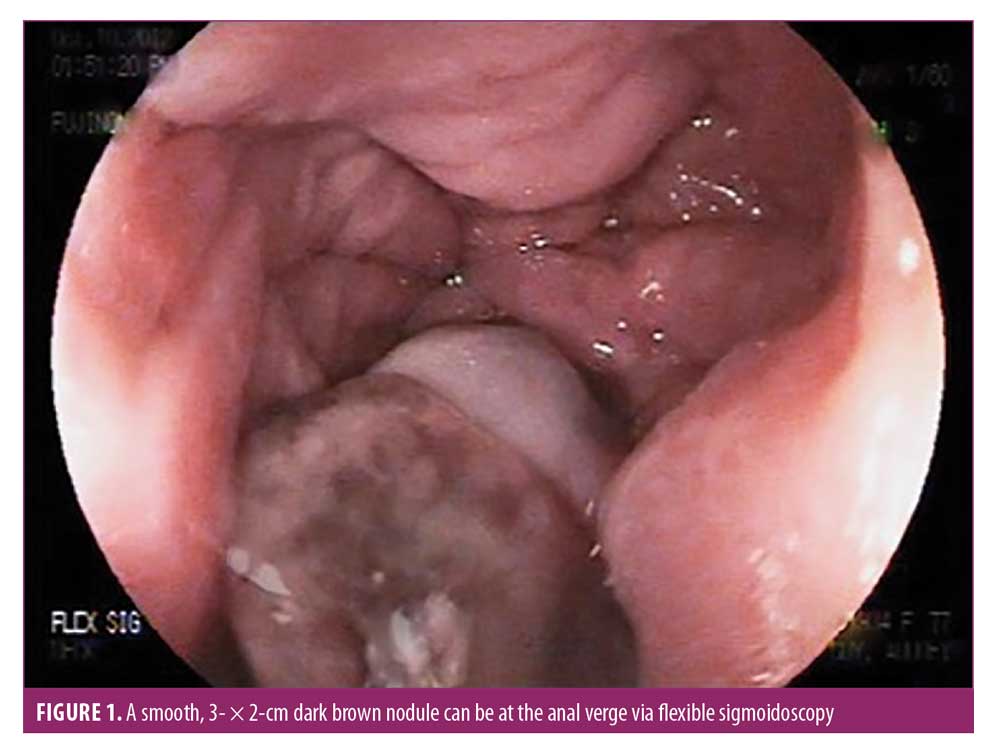

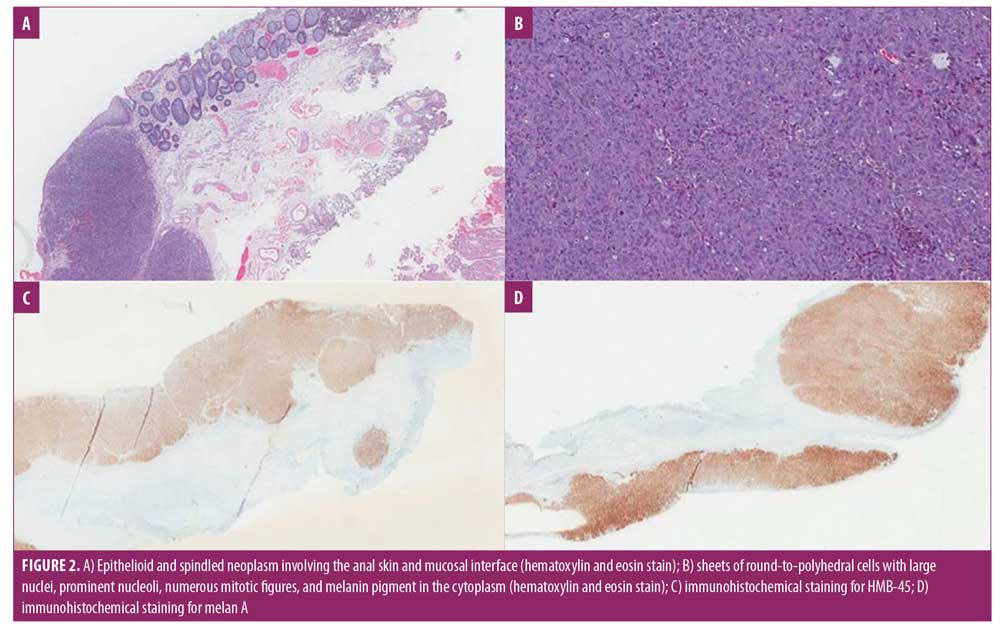

A 77-year-old Caucasian female patient with a medical history of external hemorrhoids presented with a three-month history of rectal pain, mucus discharge, and pruritus. She experienced intermittent anal spasms made worse by bowel movements. She otherwise felt well and did not report bleeding or other systemic symptoms. The patient was treated symptomatically with hemorrhoid wipes and sitz baths for several weeks. Her rectal discharge persisted to the point that the patient was requiring pads to protect her undergarments. A few months later, the patient detected a noticeable lesion near the anus. Physical examination revealed a solid polypoid hyperemic palpable mass in the anorectal canal resembling hemorrhoids. Flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed a smooth, 3- × 2-cm dark brown nodule at the anal verge (Figure 1). The patient was referred for colorectal surgical evaluation for a hemorrhoidectomy. By that time, the nodule had become ulcerated, with heaped-up edges. Excisional biopsy was performed and sent for histopathologic evaluation. Sections of the biopsy specimen demonstrated an ulcerated, multinodular pigmented epithelioid and spindled neoplasm with extensive necrosis involving the anal skin and mucosal interface (Figures 2A and 2B). Immunohistochemical staining was strongly and diffusely positive for HMB-45 and Melan A (Figures 2C and 2D) and multifocally positive for S100, confirming the diagnosis of malignant melanoma. The Breslow thickness was 9mm, and there was positive angiolymphatic invasion with microscopic satellitosis. Computed tomographic imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed metastasis to the liver and lung. Oncology was consulted and the patient was started on chemotherapy. Unfortunately, the patient succumbed to metastatic disease and passed away in six months.

Discussion

Anorectal melanoma commonly manifests with nonspecific, vague symptoms. Given the nonspecific presentation and delayed diagnosis, patients tend to present with advanced-stage disease. While the five-year overall survival rate for cutaneous melanoma is 80 percent, that for mucosal melanoma is only 25 percent.6,7 Mucosal melanoma tends to develop later in life relative to cutaneous melanoma, with a median age at diagnosis of 70 versus 55 years.3–5 Unlike cutaneous melanoma, the risk factors for anorectal melanoma are largely unknown. Epidemiologic data suggest that there is an increased risk among women, Caucasians, patients with human immunodeficiency virus, activating mutations in KIT, and a personal or family history of melanoma.1,5,8–10 Up to 30 percent of anorectal melanomas can be amelanotic and, thus, are often widely metastasized at the time of initial diagnosis.11 Lymphatic spread to the inguinal, inferior mesenteric, hypogastric or para-aortic nodal basins is common.10 Most patients with distant metastases have hepatic metastases, followed by pulmonary and bone metastases.12,13

The initial evaluation of patients with anorectal melanoma should include a total body skin check to rule out a primary cutaneous melanoma that has metastasized.14 A careful rectal examination and rectal ultrasound should be performed. Combined positron-emission tomography/computed tomographic imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should also be conducted to evaluate potential sites of metastasis to aid in staging the disease and determining further management.14,15 Currently, there is no pathologic staging system specific to anorectal melanomas. The American Joint Committee on Cancer specifically excludes anorectal melanoma from their staging system. Several studies have used the Ballantyne staging system, in which localized disease only, regional lymph node involvement, and distant metastases are classified as Stages I, II, and III, respectively.16,17

Given the rarity of this disease and the lack of randomized controlled trials, the optimal treatment approach for anorectal melanoma remains a major topic of debate. For localized anorectal melanomas, surgical therapy is the treatment of choice.18 The two most common surgical approaches include wide local excision (WLE) and abdominoperineal resection of the anorectum (APR). The choice between these surgical procedures is controversial. APR has the ability to control lymphatic spread and create bigger excision margins but is associated with significantly higher morbidity and mortality rates compared to those of WLE. There have been several retrospective studies reporting outcomes following WLE versus APR, with no clear survival advantages inherent with one approach over the other.6,12,18,19 Weylandt et al20 and Riet et al21 suggested that the decision between these surgical modalities should therefore be governed by tumor thickness. Given the faster recovery and fewer postoperation complications with a similar survival rate, WLE is recommended when the tumor thickness is between 1 and 4mm. APR should be reserved for patients in whom the tumor is thicker than 4mm and/or involves the anal sphincter.20,21 Perez et al12 also demonstrated that lymph node metastasis does not predict outcomes in patients undergoing radical resection. Furthermore, sentinel lymph node biopsy does not have an established role in patients with anorectal melanoma compared to in patients with cutaneous melanoma.6,12,13

At the time of diagnosis, up to one-third of patients have metastatic disease.23 For these patients, treatment with radiation or chemotherapy might be an option. Retrospective studies have shown that neoadjuvant irradiation might improve locoregional control but this does not have a demonstrable impact upon overall survival, regardless of stage.23 There is currently no standard systemic chemotherapy regimen that exists for metastatic anorectal melanoma. Kim et al25 reported a series of 18 patients with metastatic anorectal melanoma treated with cisplatin, vinblastine, dacarbazine, interferon alfa-2b and interleukin-2.25 A major response was seen in 44 percent of the patients and complete response occurred in 11 percent, but no increase in overall survival was found.25 Other studies using combination chemotherapy for the treatment of anorectal melanoma have not been promising.15,16,19

There are limited data on the use of immunotherapy in patients with anorectal melanoma. In a retrospective study using National Cancer Database (NCDB) data from 2004 to 2015, two-year overall survival was significantly improved for patients receiving immunotherapy versus not (49.21% vs. 42.47%; p=0.03), but the percentages of patients alive at five years were not significantly different between the two groups.19 As of yet, there are no studies looking at the use of talimogene laherparepvec in anorectal melanomas. As experience with the polyvalent melanoma vaccine continues to grow, perhaps it will prove beneficial in the treatment of anorectal melanomas.

The use of targeted therapy has revolutionized the treatment of cutaneous melanoma. As in cutaneous melanoma, 3 to 15 percent of mucosal melanomas harbor the BRAF V600 mutation, and thus, might respond well to combined BRAF and MEK inhibition.24 According to Curtin et al,25 another 39 percent of mucosal melanomas have somatic mutations or amplification of KIT alterations. As demonstrated in several case series, therapies targeted against C-KIT-activating mutations have shown significant clinical responses in patients with mucosal melanomas.27–29 Furthermore, a retrospective study by Shoushtari et al30 showed that response rates to programmed cell death receptor (PD-1) blockades in patients with mucosal melanomas were comparable to the response rates observed for cutaneous melanoma. There have not yet been studies looking at PD-1 blockade usage specifically for anorectal melanomas, but the response rates for other mucosal melanomas is promising.

Conclusion

Anorectal melanoma is an extremely rare subtype of melanoma with a poor prognosis. This disease entity presents significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. This tumor can mimic refractory hemorrhoids or other benign perianal disorders. To avoid diagnostic pitfalls, early detection is key and should always be in the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant lower gastrointestinal disorders. Bowel or rectal complaints of any type in adults with a personal or family history of cutaneous melanoma should prompt evaluation of possible metastatic disease. With the use of personalized molecular analysis, all patients with anorectal melanoma should have their tumors assayed for the presence of BRAF or KIT gene mutations. In the future, randomized controlled studies comparing different treatment modalities for anorectal melanomas are needed to determine optimal management and therapeutic protocols.

References

- Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The national cancer data base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: a summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer. 1998;83(8):1664–1678.

- Hicks CW, Pappou EP, Magruder JT, et al. Clinicopathologic presentation and natural history of anorectal melanoma: a case series of 18 patients. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):608–611.

- Callahan A, Anderson WF, Patel S, et al. Epidemiology of anorectal melanoma in the United States: 1992 to 2011. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(1):94–99.

- Tuong W, Cheng LS, Armstrong AW. Melanoma: epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(1):113–124.

- Cagir B, Whiteford MH, Topham A, et al. Changing epidemiology of anorectal melanoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(9):1203–1208.

- Yeh JJ, Shia J, Hwu WJ, et al. The role of abdominoperineal resection as surgical therapy for anorectal melanoma. Ann Surg. 2006;244(6):1012–1017.

- Nilsson PJ, ragnarsson-Olding BK. Importance of clear resection margins in anorectal malignant melanoma. Br J Surg. 2010;97(1):98–103.

- Cote TR, Sobin LH. Primary melanomas of the esophagus and anorectum: epidemiologic comparison with melanoma of the skin. Melanoma Res 2009;19(1):58–60.

- Cazenave H, Maubec E, Mohamdi H, Grange F, et al. Genital and anorectal mucosal melanoma is associated with cutaneous melanoma in patients and in families. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(3):594–599.

- Nam S, Kim CW, Baek SJ, et al. The clinical features and optimal treatment of anorectal malignant melanoma. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2014;87(3):113–117.

- Carvajal RD, Spencer SA, Lydiatt W. Mucosal melanoma: a clinically and biologically unique disease entity. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10(3):345–356.

- Perez DR, Trakarnsanga A, Shia J, et al. Locoregional lymphadenectomy in the surgical management of anorectal melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(7):2339–2344.

- Tien HY, McMasters KM, Edwards MJ, Chao C. Sentinel lymph node metastasis in anal melanoma: a case report. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2002;32(1):53–56.

- Patrick RJ, Fenske NA, Messina JL. Primary mucosal melanoma. J Amer Acad Derm. 2007;56(5):828–834.

- Seetharamu N, Ott PA, Pavlick AC. Mucosal melanomas: a review of the literature. Oncologist. 2010;15(7):772–781.

- Iddings DM, Fleisig AJ, Chen SL, et al. Practice patterns and outcomes for anorectal melanoma in the USA, reviewing three decades of treatment: is more extensive surgical resection beneficial in all patients? Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(1):40–44.

- Ballantyne AJ. Malignant melanoma of the skin of the head and neck. An analysis of 405 cases. Am J Surg. 1970;120(4):425–431.

- Matsuda A, Miyashita M, Matsumoto S, et al. Abdominoperineal resection provides better local control but equivalent overall survival to local excision of anorectal malignant melanoma: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2015;261(4):670–677.

- Taylor JP, Stem M, Yu D, et al. Treatment strategies and survival trends for anorectal melanoma: is it time for a change? World J Surg. 2019;43(7):1809–1819.

- Weyandt GH, Eggert AO, Houf M, et al. Anorectal melanoma: surgical management guidelines according to tumour thickness. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(11):2019–2022.

- Riet M, Giard RW, Wilt JH, et al. Melanoma of the anus disguised as hemorrhoids: surgical management illustrated by a case report. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(7):1745–1747.

- Thibault C, Sagar P, Nivatvongs S, et al. Anorectal melanoma—an incurable disease? Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(6):661–668.

- Tchelebi L, Guirguis A, Ashamalla. Rectal melanoma: epidemiology, prognosis, and role of adjuvant radiation therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(12):2569–2575.

- Johnson DB, Carlson JA, Elvin JA, et al. Landscape of genomic alterations and tumor mutational burden in different metastatic melanoma subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15):9536–9536.

- Kim KB, Sanguino AM, Hodges C, et al. Biochemotherapy in patients with metastatic anorectal mucosal melanoma. Cancer. 2004;100(7):1478–1483.

- Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, et al. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(26): 4340–4346.

- Oualla K, Mellas N, Elmrabet F, et al. Primary anorectal melanomas interest of targeting C-KIT in two cases from a series of 11 patients. J Canc Therapy. 2014;5(3):225–230.

- Tacastacas J, Bray J, Cohen YK, et al. Update on primary mucosal melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):366–375.

- Hodi, Corless CL, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Imatinib for Melanomas Harboring Mutationally Activated or Amplified KIT arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun damaged skin. J Clin Oncology. 2013;31(26):3182–3189.

- Shoushtari AN, Munhoz RR, Kuk D, et al. The efficacy of anti-PD-1 agents in acral and mucosal melanoma. Cancer. 2016;122(21):3354–3362.