J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(10):41–51.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(10):41–51.

by Ishika Muradia, MD; Niti Khunger, MD; and Amit Kumar Yadav, MD

Drs. Ishika and Khunger are with Department of Dermatology and Sexually Transmitted Diseases at Vardhman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital in Delhi, India. Dr. Yadav is with the Department of Pathology at Vardhman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital in Delhi, India

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Acquired melanocytic nevi are very common and usually multiple. Corroborating clinical and dermoscopic diagnosis with histopathology will help in differentiating benign nevi from malignant and thus, obviate the need of biopsy in benign nevi. Additionally, it helps in predicting the chances of recurrence after removal leading to better treatment outcome and patient counselling.

Objective. This study aimed to examine the clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological features of common acquired melanocytic nevi. It also assessed the association between the two.

Methods. One hundred Indian patients aged 18 years or older with clinical features suggestive of common acquired melanocytic nevi were enrolled in the study. The nevi were assessed clinically and dermoscopically using ABCD rule and if found benign, were excised using shave excision. The specimen obtained was sent for histopathological examination.

Results. The age of the patients varied from 18 to 50 years with 83 females and 17 males. There was a 100 percent concordance rate between the clinical and histopathology diagnosis of intradermal nevi whereas higher discordance rate for that of compound nevi. Hair was present in a total 25 nevi and all were intradermal nevi on histopathology. Dermoscopy features suggestive of compound nevi were biaxial symmetry, presence of pigment network, and structureless homogenous areas. Features suggestive of intradermal nevi on dermoscopy were presence of blue-grey color, globules, structureless areas, and branched streaks.

Conclusion. This is a pioneering study correlating the clinical and dermoscopic features with histopathology in skin of color. There is 100 percent concordance rate between clinical and histopathological diagnosis of intradermal nevi. Dermoscopy is a useful non-invasive tool for assessing the presence of certain dermoscopic features and predicting the type of nevi and their recurrences.

Keywords. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathological analysis, common acquired melanocytic nevi, association.

Acquired melanocytic nevus (AMN) are benign proliferative lesions of uniform melanocytes which occur on the skin after birth.1 They are initially located at the intradermal-epidermal junction and over time tend to migrate into the dermis, slowly enlarge symmetrically, stabilize and regress with subsequent morphological changes.2,3 Acquired melanocytic nevi are very common and are usually multiple. The number of melanocytic nevi increases from childhood to midlife, with the majority developing during second and third decades, and decreasing progressively thereafter.2,3 The prevalence of acquired nevi varies according to ethnicity. The prevalence is low in dark skinned people and higher in lighter skinned people.2 No sex predilection is seen.8 Environmental exposure to UV radiation is a critical inciting factor for the development of nevomelanocytic nevi.2

Acquired nevi includes common acquired melanocytic nevi (CAMN) and also includes uncommon varieties such as agminated nevi, balloon cell nevi, cockade nevi, halo nevi, Meyerson nevi, neural nevi, nevus spilus, recurrent melanocytic nevi, Miescher nevi, and Unna nevi.4 Common acquired melanocytic nevi are classified into three common clinical types: junctional, intradermal and compound nevi according to the site of the nevus cell nests.1 These are benign neoplasms of melanocytic nevus cells that begin at intradermal-epidermal junction (junctional nevus), and over time tend to migrate into the dermis while a component remains in contact with the basal layer (compound nevus). At the end of this process, the nevus cells are completely detached from the overlying epidermis (intradermal nevus).3 The junctional nevus is a macular lesion with slight accentuation of skin markings. Compound nevi shows variable degrees of elevation and light brown shade as compared to junctional nevi. Intradermal nevi are more elevated and a lighter shade of brown or may be even skin-colored compared to compound nevi.4

A dermoscope (dermatoscope) is a non-invasive, diagnostic tool that visualizes the subtle clinical patterns of skin lesions and subsurface skin structures that are normally not visible to the unaided eye. The basic principle of dermoscopy is transillumination of a lesion and studying it with a high magnification. Light incident on skin undergoes reflection, refraction, diffraction, and absorption that are influenced by physical properties of the skin. Therefore, various linkage fluids have been used to enhance the translucency of skin.5

Most of the CAMN have one or more of the following dermoscopic features: a network, globules, dots, streaks, and structureless areas. These structures are regular in shape and size with a uniform distribution.6

There have been very few studies on clinical and dermoscopic patterns of common acquired melanocytic nevi in the Indian population. Hence this study is being undertaken.

Methods

After taking proper approval from the ethical committee, a Prospective cohort study was carried out in a tertiary care centre for a duration of 18 months. The sample size of 100 nevi was taken. Adult males and females of more than 18 years of age with clinical features suggestive of common acquired melanocytic nevi and who have not undergone any prior procedure for its removal, were included in the study after obtaining proper informed consent. Patients with nevi showing dermoscopic findings suggestive of atypical nevi or suspicious changes or with histopathological findings of atypical nevi or malignant changes, nevi over nail bed, genitals and mucosa, and patients with history of keloid formation were excluded from the study. All patients underwent a detailed history pertaining to name, age, sex, occupation, onset, duration, progression, history of preceding trauma, family history, treatment history, and history of keloid formation at previous scar site. Detailed examination of the melanocytic nevi was performed for number, site, size, shape, border, color, morphology, presence of hair, and were recorded in a predesigned proforma and a clinical diagnosis was made.4 (Table 1)

Dermoscopic assessment was performed using Dermlite DL4 dermoscope (3 Gen, California, USA) using both polarized and nonpolarized mode. The images of all the relevant findings were taken under both 10x and 20x optical zoom, and recorded in the proforma. Dermoscopic assessment was done at the initial visit according to ABCD rule to observe various dermoscopic features and confirm that the nevi are benign.7 (Tables 2–4)

Shave excision of the nevus was performed using a 15 number surgical blade and biopsy specimen was collected in a glass vial containing 10% formalin for histopathological confirmation. Haemostasis was obtained using local compression. If bleeding was not stopped on compression, coagulation mode of radiofrequency current using Ellman Surgitron® Dual RFTM 120 (New York, USA) machine with a solid 2mm ball probe was used.

Categorical variables were presented in number and percentage (%) and continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and median. Normality of data was tested by a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. If the normality was rejected then a non parametric test was used. Quantitative variables were compared using Mann-Whitney Test (as the data sets were not normally distributed) between the two groups. Qualitative variables were associated using Chi-Square test/Fisher’s Exact test.

Inter-rater kappa agreement was used to find the strength of agreement between clinical diagnosis and histopathological diagnosis. The data analysis was completed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0.

Results

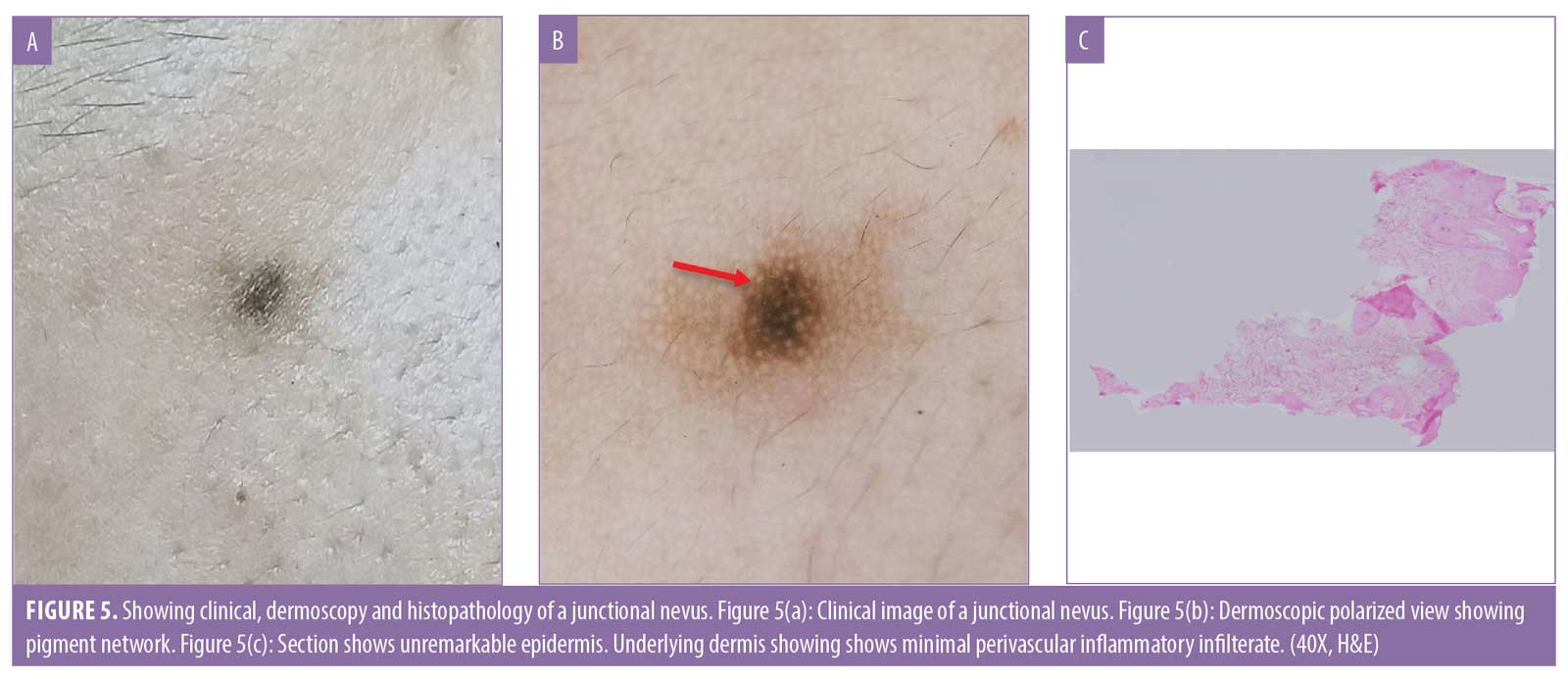

The age of the patients varied from 18 to 50 years with mean age (years) of patients 23.59 ± 8.1. (Table 5) Eighty-three patients were females and only 17 were males. (Table 6) Majority (95%) of nevi were present over face, 3 percent over neck, 1 percent over chest and 1 percent over back. The smallest nevus was of size 1mm and largest was 7mm with median (IQR) of 3.5 (3–5). Out of 100 nevi, 43 percent were oval, 42 percent were round, 10 percent were symmetrical and 5 percent were asymmetrical. Ninety four percent nevi had regular borders and remaining 6 percent had irregular borders. Dark brown was the most common color observed, seen in 36 percent patients, 30 percent of the nevi were hyperpigmented, 24 percent were light brown and 10 percent nevi had flesh tone color. (Table 7) Seventy percent nevi were papule, 21 percent were dome shaped papule, 5 percent were macules and 4 percent were papillomatous papule. (Table 7) (Figure 1) Based on clinical diagnosis 61 percent nevi were compound nevi, 34 percent were intradermal nevi and 5 percent were junctional nevi. (Table 7) Out of the 100 nevi included, hair was present in 25 nevi.

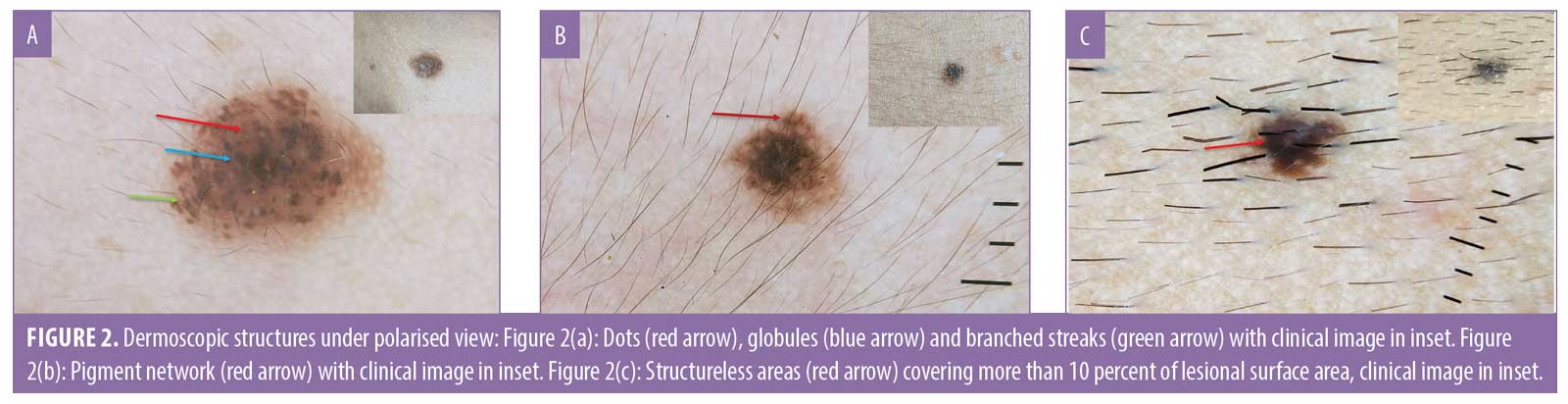

Dermoscopic assessment was performed using ABCD rule. There was axial symmetry along both axes in 60 percent nevi, axial asymmetry along one axis in 39 percent nevi and axial asymmetry along two axes in 1 percent nevi. (Table 8) The border sharpness score was 0 in 32 percent nevi, 1 in 11 percent nevi, 2 in 28 percent nevi, 3 in 11 percent nevi, 4 in 17 percent nevi and 5 in 1 percent nevi. (Table 9). Multiple colors were seen in a single nevi with dark brown color in 86 percent nevi, black in 57 percent nevi, light brown in 46 percent nevi, blue-grey in 11 percent nevi and white color was seen at some places in 10 percent nevi. On scoring the color, 78 percent nevi had score of 2, 16 percent nevi had score of 3 and 6 percent nevi had score of 1. (Table 10) On dermoscopy, different structures were observed in nevi. Pigmented dots were seen in 89 percent nevi, globules in 61 percent nevi, structureless areas in 59 percent nevi, pigment network in 37 percent nevi and branched streaks in 6 percent nevi. (Figure 2) Three different dermoscopic structures were seen in 53 percent nevi, 2 in 40 percent nevi, 1 in 5 percent nevi and 4 in 2 percent nevi. (Table 11) According to the total dermoscopic score all the nevi were benign with the score of less than 4.75. Mean total dermoscopic score of nevi was 3.02 ± 0.89 with median (IQR) of 2.8 (2.4–4). (Table 12)

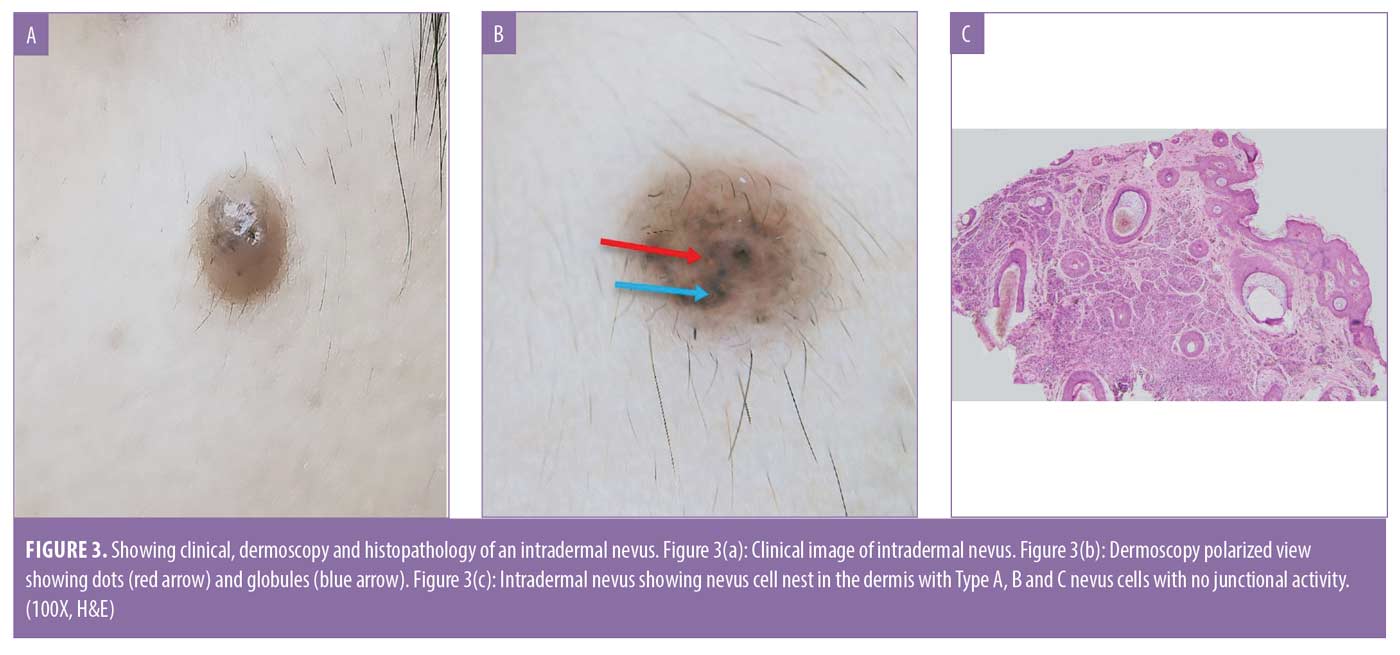

On histopathological examination, 87 percent of the nevi were found to be intradermal, 8 percent were compound and in 5 percent nevi the tissue was insufficient for diagnosis. (Table 13, Figure 3)

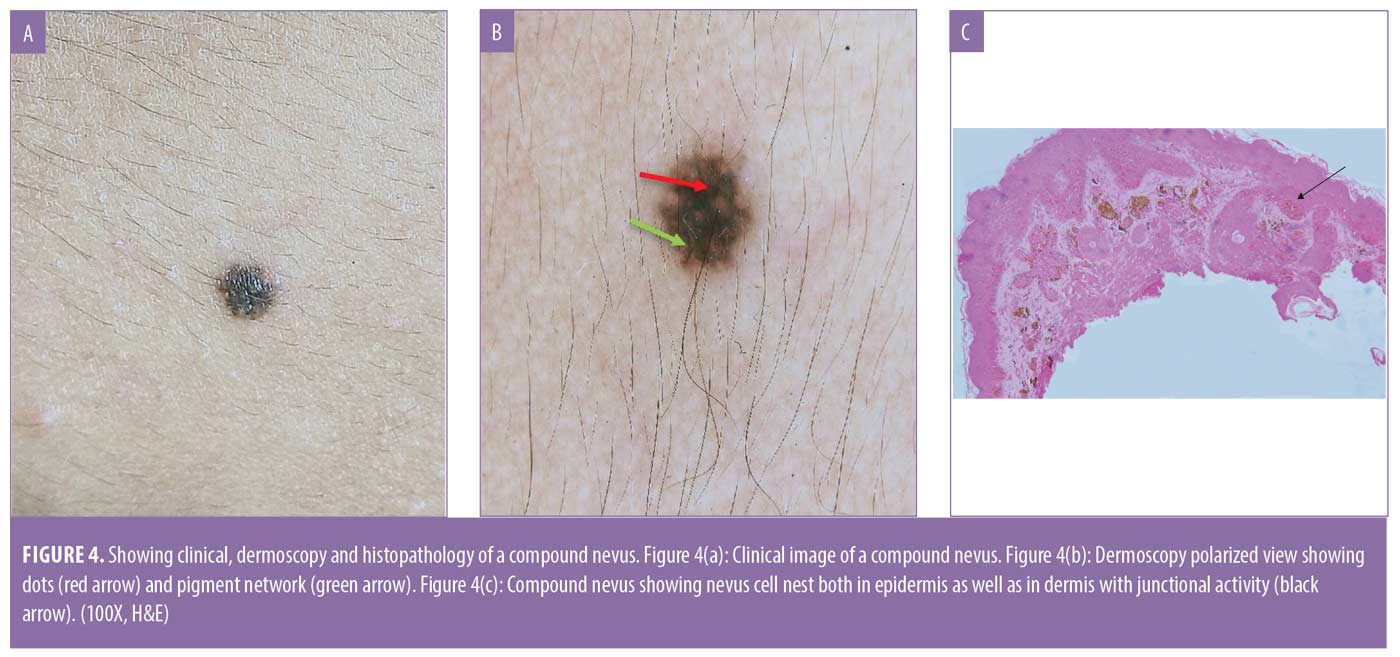

Five nevi were clinically diagnosed as junctional nevi and all had insufficient tissue on histopathology. Out of 61 clinically diagnosed compound nevi, only eight were confirmed as compound on histopathology and rest 53 nevi were intradermal. All the clinically diagnosed intradermal nevi were confirmed as intradermal on histopathology.

Significant association was seen in the distribution of clinical diagnosis with histopathological diagnosis primarily due to intradermal nevi (p<0.05). (Table 14) Since the 5 nevi which were clinically diagnosed as junctional could not be confirmed on histopathology due to tissue insufficiency, 95 of 100 nevi were taken for further analysis. As all the clinically diagnosed intradermal nevi were confirmed as intradermal on histopathology, there was a 100 percent concordance between the clinical and histopathology diagnosis. For compound nevi there was higher discordance rate between clinical and histopathology diagnosis. Overall concordance rate between histopathological diagnosis and clinical diagnosis was 44.21 percent and overall discordance rate was 55.79 percent primarily due to clinically diagnosed compound nevi. Poor agreement exists between histopathological diagnosis and clinical diagnosis with kappa 0.098 and p value 0.027. (Table 15)

All the compound nevi were seen in patients less than 20 years of age, which was significantly higher as compared to 43.68 percent of intradermal nevi. Significant association was seen between patient’s age (years) with type of nevi. (p<0.05) Median (IQR) of age (years) in intradermal nevi was 22 (18–29) which was significantly higher as compared to compound nevi with 17 (16.75–20). (Table 16)

Majority (82.11%) of patients were female. All the compound nevi and 80.46 percent of intradermal nevi were present in female. Males were 19.54 percent and all had intradermal nevi. (Table 17)

Fifty percent of compound nevi had onset at less than 10 years age and rest 50 percent had onset between 11 to 20 years age. Majority (36.78%) intradermal nevi had onset between 11 to 20 years age, 32.18 percent had onset at less than 10 years age and 31.03 percent had onset at more than 20 years age. No significant association was seen in the distribution of age of onset (years) with type of nevi. (p>0.05). No significant association was seen between duration and type of nevi. (Table 18)

Face was the most common site. All the compound nevi and 94.25 percent of intradermal nevi were present over face which was significantly higher as compared to other sites. Neck was the second most common site with 3.45 percent of intradermal nevi. Both chest and back had 1.15 percent of intradermal nevi. Shape was symmetrical in 50 percent of compound nevi which was significantly higher as compared to 5.75 percent of intradermal nevi. Shape was oval in 44.83 percent of intradermal nevi which was significantly higher as compared to 12.50 percent of compound nevi. Significant association was seen in the distribution of shape with type of nevi. (p<0.05) Most common morphology observed was papule seen in all the compound nevi and 71.26 percent intradermal nevi. Nevi were dome shaped papules in 24.14 percent intradermal nevi and were papillomatous papules in 4.60 percent intradermal nevi. Regular borders were seen in 87.50 percent of compound nevi and 94.25 percent of intradermal nevi. Majority of nevi were dark brown with 62.50 percent of compound nevi and 31.03 percent of intradermal nevi, hyperpigmentation was seen in 37.50 percent of compound nevi and 29.89 percent of intradermal nevi. None of the compound nevi had flesh tone whereas 27.59 percent intradermal nevi had flesh tone. Median (IQR) of size (mm) in compound nevi was 3 (2.75–3) and intradermal nevi was 4 (3–5) with no significant association between them. (Table 19) Hair was present in total 25 nevi and all were intradermal nevi on histopathology. (Table 20)

All the histopathologically diagnosed compound nevi were clinically diagnosed as compound which was significantly higher as compared to 60.92 percent of intradermal nevi which were clinically diagnosed as compound nevi. (p<0.05) (Table 19)

Axial symmetry was present in 75 percent of compound nevi and 59.77 percent of intradermal nevi. Axial asymmetry along one axis was seen in 25 percent of compound nevi and 39.08 percent of intradermal nevi. Biaxial asymmetry was seen in none of the compound nevi and 1.15 percent of intradermal nevi with no significant difference in distribution between them. No significant association was seen in the distribution of asymmetry score with type of nevi (p>0.05). (Table 21)

Majority of intradermal and compound nevi had a border sharpness score of 0 and 4 respectively with no significant association between the distribution of border sharpness score with type of nevi. (p>0.05) (Table 22)

On dermoscopy, multiple colors were seen in a single nevus. Black color was seen in all of the compound and intradermal nevi, dark brown color was seen in all the compound nevi and 83.91 percent of intradermal nevi, light brown color was seen in 62.50 percent of compound nevi and 42.53 percent of intradermal nevi. Blue-grey and white color were present in 12.64 percent and 11.49 percent of intradermal nevi respectively and none of the compound nevi. No significant association was seen in the distribution of colors with type of nevi (p>0.05). (Table 23)

Pigment network were seen in all the compound nevi which was significantly higher as compared to 29.89 percent intradermal nevi. Globules were seen in 65.52 percent of intradermal nevi which was significantly higher as compared to 25 percent of compound nevi. Structureless areas were seen in 62.50 percent of compound nevi and 60.92 percent of intradermal nevi and branched streaks were seen in none of the compound nevi and 6.90 percent of intradermal nevi with no significant difference in distribution between them. No significant association was seen in the distribution of dermoscopic structures with type of nevi except for pigment network and globules. (p>0.05) (Table 24)

Median (IQR) of total dermoscopic score in compound nevi was 2.65 (2.35–3.15) and intradermal nevi was 2.8 (2.5–4) with no significant association between them. No significant association was seen in total dermoscopic score with type of nevi. (p>0.05) (Table 25) All the nevi were benign on dermoscopic assessment with total dermoscopic score of less than 4.75, which was confirmed on histopathology.

Discussion

We did a detailed prospective cohort study of 100 common acquired melanocytic nevi and studied its clinical and dermoscopic features and confirmed the diagnosis on histopathology. We used shaved excision for removal of the nevi.

The mean age of patients in our study was 23.59 ± 8.1 years with majority of cases seen in second and third decade with 48 percent and 36 percent patients respectively. A study by Ghosh et al8 showed similar results, with a mean age of 28 years, and maximum number of patients in the third decade followed by the second with 32.4 percent and 25.6 percent patients respectively. Most of the other studies had a mean age of 32 years.9–11

This study consisted of 83 percent females and 17 percent males which was very similar to a study by Bong et al12. Since there is no sex predilection, this difference might be due to greater cosmetic concern in females.

One hundred patients included in our study had multiple nevi of which a representative nevus was chosen for further evaluation. Forty one percent had onset in the second decade, 32 percent at less than 10 years and 27 percent at more than 20 years of age. In a study by Malladi et al13, of the 115 acquired melanocytic nevi, 47 percent had onset in the first decade, 43 percent had onset in second decade and 10 percent had onset after 20 years of age. They included patients with age ranging from five months to 61 years whereas in our study patients age ranged from 18 to 50 years which could be the reason for discordance.

The most common site in our patients was the face (95%), followed by the neck (3%), back (1%), and trunk (1%). Similar results were seen Ghosh et al8, 92 percent nevi were located over face, head and neck followed by trunk 7 percent and arm consisted of 1 percent. Majority of patients who have facial melanocytic nevi desire removal due to cosmetic concerns.

The mean size (mm) of nevi was 3.6 ± 1.31 with diameter ranging from 1–7mm. In a study of 684 acquired benign melanocytic nevi by Osman Köse14, the nevi diameter ranged from 2–10mm. İyidal et al15 studied 10,047 acquired melanocytic nevi and found that the size of 98.3 percent nevi was less than or equal to 5mm.

Majority of nevi in our study had oval (43%) shape followed by round shape (42%). Majority of nevi seen were intradermal followed by compound nevi hence oval and round shapes were commonly observed clinically. In 94 percent nevi the borders were regular. This could be because all the nevi included in our study were benign. Ghosh et al8 performed a histomorphological analysis of 104 benign melanocytic nevi and observed that 65 percent nevi had regular borders, but did not comment upon the shape of the nevi which was done in our study.

In our study, 36 percent of nevi had dark brown color followed by hyperpigmented (30%), light brown (24%), and flesh tone (10%). Twenty five percent of nevi were hairy. Bong et al12 observed in his study that 69 percent benign melanocytic nevi were brown colored and 35 percent were hairy.

On assessing shape, 70 percent of nevi were papule, 21 percent were dome shaped papule, 5 percent were macule, and 4 percent were papillomatous papule. This is because majority of the nevi were intradermal followed by compound nevi. Porter et al16 in his study commented that 49 percent of the nevi were flat and 51 percent were raised clinically, but did not elaborate the raised lesion as papule, dome shaped or papillomatous lesion, which was done in our study.

Based on clinical diagnosis, 61 percent of the nevi were compound, 34 percent were intradermal, and 5 percent were junctional. In a study by Porter et al16, 69 percent nevi had a clinical diagnosis of intradermal nevi, 14 percent

compound nevi and 16.6 percent junctional nevi.

Different dermoscopic algorithms can be used for differentiating benign melanocytic nevi from melanoma. ABCD algorithms were used in our study for assessing all the common acquired melanocytic nevi. Only those which were benign on dermoscopic assessment were included in our study for further intervention.

On dermoscopic assessment, 60 percent nevi were symmetrical, 39 percent nevi had asymmetry along one axis and only 1 percent had biaxial asymmetrical. These results were not in concordance with that of original study by Stolz et al17 in which he found that 15 percent of benign melanocytic nevi were symmetrical, 61 percent had asymmetry along one axis and 21 percent had biaxial asymmetry.

On dermoscopy, in 32 percent nevi the border was sharply cut off in all the segments. In 28 percent nevi the perimeter was abruptly cut off in two segments. In 17 percent nevi the perimeter was abruptly cut off in four segments and only 1 percent had abrupt perimeter cut off in five segments. Stolz et al17 found that in 60 percent benign melanocytic nevi the border was sharply cut off in all the segment and in 10 percent the boarder had an abruptly cut off perimeter in four segments.

Dermoscopic assessment revealed that 86 percent nevi had dark brown color, 57 percent had black color, 46 percent nevi had light brown color, 11 percent nevi had blue-grey color and 10 percent nevi had white color. In a single nevus, different colors could be seen, 78 percent nevi showed two different colors, 16 percent nevi showed three different colors. Single color was seen in only 6 percent of the nevi. Stolz et al16 revealed that 56 percent of the benign melanocytic nevi had two colors, 29 percent had three colors, and 10 percent had more than three colors. In a study by Heck et al18, on dermoscopic assessment, 81 percent nevi showed light brown color, 36 percent showed dark brown color and 1.5 percent showed black color. Single color was seen in 83 percent nevi, two different colors were seen in 16 percent nevi, and more than or equal to three colors were seen in 0.5 percent nevi. These observations were in discordance with our study.

Different dermoscopic structures were observed in the nevi, 89 percent nevi had dots, 61 percent had globules, 59 percent nevi had structureless areas, 37 percent nevi had pigment network and 6 percent had branched streaks in 6 percent of patients. Vascular structures were seen in only 5 percent nevi. In a study by Heck et al18, on dermoscopic assessment of 195 benign melanocytic nevi 75 percent showed structureless areas, 31 percent showed globules, 14 percent showed dots, 2 percent showed pigment network and vascular structures were seen in 64.61 percent nevi.

According to Stolz et al17 less than or equal to three dermoscopic structures were seen in 90 percent of benign melanocytic nevi. In our study, 98 percent nevi had less than or equal to three dermoscopic structures which shows concordance with the study by Stolz et al.17 A comparison of dermoscopy assessment of compound and intradermal nevi with other studies was also performed. (Table 26)

All the nevi in our study had a total dermoscopic score of less than 4.75 which was considered as threshold for a benign melanocytic nevus and all were diagnosed as benign melanocytic nevi.7,17 Mean value of total dermoscopic score of nevi was 3.02 ± 0.89 with median (IQR) of 2.8(2.4–4). Out of all nevi, 95 percent were correctly diagnosed as melanocytic nevi on dermoscopy, and the remaining 5 percent had insufficient tissue on histopathology so they could not be commented upon.

In a study by Nachbar et al19, melanocytic nevi were correctly assessed by the ABCD rule in 93 of 103 cases (90.3%). The mean ABCD score was 4.27 ± 0.99 which was higher than our study.

Histopathology is the gold standard for making the diagnosis. On histopathology, 87 percent of the nevi were intradermal, 8 percent were compound nevi, and for 5 percent nevi the tissue was insufficient for diagnosis. Heck et al18 in their study performed shave excision of 224 acquired melanocytic nevi and found that on histopathology 92 percent nevi were intradermal, 8 percent were compound nevi. In a study by Ferrandiz et al.12,20 shave excision of 204 nevi was done and on histopathological examination 78.4 percent nevi were intradermal, 21.6 percent were compound. In both studies none of the cases included were diagnosed as junctional nevi. However, in the present study all the clinically diagnosed junctional nevi had insufficient tissue for histopathological diagnosis whereas it was adequate for compound and intradermal nevi. This could be because shave excision could not provide a proper specimen for junctional nevi since all were macules.

Since clinically diagnosed junctional nevi had insufficient tissue for histopathological diagnosis, only compound and intradermal nevi could be analysed further. In previous studies the correlation between clinical and histopathological diagnosis was not done. In the present study, all the clinically diagnosed intradermal nevi were intradermal on histopathology with 100 percent concordance rate. Out of 61 clinically diagnosed compound nevi only 8 (13.11%) were compound on histopathology with the rest being intradermal and thus, the overall discordance rate was higher.

There was significant association between age of the patients and the type of nevi with all the compound nevi occurring in patients with less than 20 years age. There was no significant association between the gender distribution of the patients with type of nevi. All of the compound nevi had onset in the first and second decade. The majority of intradermal nevi had onset in the second decade with slight decrease in the third decade. Wang et al9 conducted a study on 2,929 acquired melanocytic nevi and found that the percentage of intradermal nevi gradually increased with age whereas on the contrary the percentage of junctional and compound nevi decreased with increasing age.

Face was the most common site for both compound and intradermal nevi with no significant association between the site and type of nevi. Of all the nevi present over face, 91.11 percent were intradermal nevi and 8.89 percent were compound nevi. In a study by Li et al21 similar results were seen with 85.5 percent intradermal nevi, 13 percent compound nevi and 1.5 percent junctional nevi. The majority of compound nevi had symmetrical and round shapes. The majority of intradermal nevi had round and oval shaped with significant association between the shape and type of nevi. Majority of intradermal and compound nevi were regular. Dark brown followed by hyperpigmentation were the most common observed colors. Hair was present in none of the compound nevi and 28.73 percent of dermal nevi. The morphology of the nevi was not significantly associated with the type of the nevi. Majority of both compound and intradermal nevi were papules.

No significant association was seen between the dermoscopy structures score with type of nevi. The median (IQR) of the total dermoscopic score in compound nevi was 2.65 (2.35–3.15) and intradermal nevi was 2.8(2.5–4) with no significant association between them. Nachbar et al19 in their study found that in junctional and compound nevi the total dermoscopic score or ABCD score was between 2 to 6 with no significant differences between them. In our study we could not comment upon junctional nevi due to insufficient tissue for histopathology in clinically diagnosed junctional nevi.

Conclusion

Clinical diagnosis of compound nevi did not correlate well with the histopathological diagnosis. The majority of clinically diagnosed compound nevi found to be intradermal on histopathology. All of the clinically diagnosed intradermal nevi were intradermal on histopathology. Clinically diagnosed junctional nevi could not be evaluated further because of insufficient tissue sample for histopathology.

All of the nevi diagnosed as benign using the ABCD rule on dermoscopy were benign on histopathology as well. Dermoscopy features suggestive of compound nevi were biaxial symmetry, presence of pigment network, and structureless homogenous areas and these nevi are less likely to recur. Features suggestive of intradermal nevi on dermoscopy were presence of blue-grey color, globules, structureless areas, and branched streaks. Dermoscopy is a useful non-invasive tool for assessing the presence of the above features and predicting the type of nevi and their chances of recurrence.

Shave excision is a minimally invasive and easily performed procedure. It can also provide a proper histopathological specimen for both intradermal and compound nevi but not for clinically diagnosed junctional nevi.

References

- Wang DG, Huang FR, Chen W, et al. Clinicopathological Analysis of Acquired Melanocytic Nevi and a Preliminary Study on the Possible Origin of Nevus Cells. Am J of Dermatopathol. 2020;42:414–422.

- Grichnik JM, Rhodes AR, Sober AJ. Benign neoplasias and hyperplasias of melanocytes. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Wolf K, editors. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. McGraw Hill: Newyork; 2012. p. 1384–1392.

- Stefanaki A, Antoniou C, Stratigos A. Benign melanocytic proliferations and melanocytic nevi. In: Griffith CEM, Barker J, Bleiker T, Chalmers R, Creamer D, editors. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 9th ed. Blackwell Publishing: Oxford; 2016. P. 132.18–132.32.

- Sardana K, Chakravarty P, Goel K. Optimal management of common acquired melanocytic nevi (moles): current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:89–103.

- Nischal KC, Khopkar U. Dermoscope. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:300–303.

- Rao BK, Wang SQ, Murphy FP. Typical dermoscopic patterns of benign melanocytic nevi. Dermatol Clin. 2001;19:269–284.

- Weigert U, Burgdorf WHC, Stolz W. ABCD rule. In: Marghoob AA, Manehy J, Braun RP, editors. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare Publishing; 2012. p. 113–117.

- Ghosh A, Ghartimagar D, Thapa S, et al. Benign melanocytic lesions with emphasis on melanocytic nevi–A histomorphological analysis. J Path Nepal. 2018;8:1384–1388.

- Wang SQ, Marghoob AA, Scope A. Principles of dermoscopy and dermoscopic equipment. In: Marghoob AA, Manehy J, Braun RP, editors. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare Publishing; 2012. p. 3–9.

- Tursen U, Kaya TI, Ikizoglu G. Round excision of small, benign, papular and dome-shaped melanocytic nevi on the face. Int J Dermatol.2004;43:844–846.

- Gambichler T, Senger E, Rapp S, et al. Deep shave excision of macular melanocytic nevi with the razor blade biopsy technique. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:662–666.

- Bong JL, Perkins W. Shave excision of benign facial melanocytic naevi: a patient’s satisfaction survey. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:227–229.

- Malladi NSN, Chikhalkar SB, Khopkar U, et al. A descriptive observational study on clinical and dermoscopic features of benign melanocytic neoplasms. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:251–261.

- Köse O. Efficacy of the carbon dioxide fractional laser in the treatment of compound and dermal facial nevi using with dermatoscopic follow-up. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:498–502.

- İyidal AY, Gül Ü, Kılıç A. Number and size of acquired melanocytic nevi and affecting risk factors in cases admitted to the dermatology clinic. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:375–380.

- Porter JM, Treasure J. Excision of benign pigmented skin tumours by deep shaving. Br J Plast Surg.1993;46:255–257.

- Stolz W. ABCD rule of dermatoscopy: a new practical method for early recognition of malignant melanoma. Eur J Dermatol. 1994;4:521–527.

- Heck R, Ferrari T, Cartell A, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic (in vivo and ex vivo) predictors of recurrent nevi. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:179–184.

- Nachbar F, Stolz W, Merkle T, et al. The ABCD rule of dermatoscopy: high prospective value in the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:551–559.

- Ferrandiz L, Moreno-Ramirez D, Camacho FM. Shave excision of common acquired melanocytic nevi: cosmetic outcome, recurrences, and complications. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1112–1115.

- Li QX, Swanson DL, Tu P, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of surgically treated melanocytic nevi: a retrospective study of 1046 cases. Chin Med J. 2019;132:2027–2032.