J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(12):46–51.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(12):46–51.

by Daniel Piacquadio, MD; Brian Berman, MD, PhD; Daniel M. Siegel, MD; Neal Bhatia, MD; Jason Brocato, PhD; Nicholas Squittieri, MD; and David M. Pariser, MD

Drs. Piacquadio and Bhatia are with Therapeutics, Inc., in San Diego, California. Dr. Berman is with Center for Clinical and Cosmetic Research in Aventura, Florida, and University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Miami, Florida. Dr. Siegel is with The State University of New York Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn, New York, and Brooklyn Campus of the VA NY Harbor Healthcare System in Brooklyn, New York. Drs. Brocato and Squittieri are with Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. in Princeton, New Jersey. Dr. Pariser is with Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia, and Virginia Clinical Research, Inc. in Norfolk, Virginia.

FUNDING: The studies were supported by DUSA Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Medical writing support was funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

DISCLOSURES: DP is an employee of Therapeutics, Inc. BB has received grants and consulting fees from Almirall; Biofrontera; Bristol Myers Squibb; DUSA Pharmacuticals, Inc.; Evoimmune; Mediwound; MINO Labs; Pfizer; and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. DS has received honoraria and/or consultant fees and/or investigator grants/research funding from Avita; Biofrontera AG; Cara Therapeutics; DermaSensor, Inc.; Medforce Technologies, Inc.; MedX Health; Pulse Biosciences; Regeneron; Sanofi Genzyme; SciBASE; Sol-Gel Technologies; Strata Skin Sciences; UCB; and Verrica Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and may own stock and/or stock options in Biofrontera AG; Greenway Therapeutix, Inc.; Logical Images; Modernizing Medicine; Novascan; Or-Genix Therapeutics; Palmm; Plasmend; RaMedical; Seaspire Skincare; SkinVision; and Tetros Group. NB is an advisor, consultant, and investigator for AbbVie; Almirall; Arcutis; Beiersdorf; Biofrontera; Bristol Myers Squibb; Boehringer Ingelheim; Cara; Dermavant; Eli Lilly; EPI Health; Ferndale; Galderma; InCyte; ISDIN; Johnson & Johnson; LaRoche-Posay; LEO Pharma; Ortho Dermatologics; Pfizer; Regeneron; Sanofi; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.; and Verrica Pharmaceuticals, Inc. JB and NS are employees of Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. DMP has received honoraria and grants or research funding as a consultant, advisory board participant, or investigator from Bickel Biotechnology, Dermira, LEO Pharma US, Novartis, Pfizer, and Regeneron; honoraria as a consultant or data monitoring board participant from Biofrontera AG, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Sanofi; and grants or research funding as an investigator from Almirall; Amgen; AOBiome, LLC; Asana Biosciences, LLC; Celgene; Eli Lilly; Menlo Therapeutics; Novo Nordisk A/S; and Ortho Dermatologics.

ABSTRACT: Background. Actinic keratoses (AKs) are precancerous, dysplastic, epidermal lesions caused by chronic sun exposure that may progress to squamous cell carcinoma. Aminolevulinic acid 20% solution with blue light photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT) has previously been shown to be superior to vehicle plus PDT (VEH-PDT) for treatment of AKs of the face, scalp, and upper extremities.

Objective. We report detailed patient satisfaction data for ALA-PDT.

Methods. Patient satisfaction for ALA-PDT versus VEH-PDT and patient-reported acceptability of ALA-PDT versus previous treatments for AKs were assessed in three randomized, vehicle-controlled studies (two Phase II and one Phase III) in adults. Patients in the Phase II studies were treated on the scalp and/or face, and those in the Phase III study were treated on the upper extremities.

Results. A total of 234, 166, and 269 patients were enrolled in the two Phase II studies and one Phase III study, respectively; overall, 79.8 percent of patients were male. Overall treatment satisfaction ranged from 79 to 88 percent for ALA-PDT, compared to 35 to 56 percent for VEH-PDT. Patients generally considered ALA-PDT to be equivalent to or more acceptable than prior treatments, including cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, previous PDT, and surgery. Similar proportions of patients receiving ALA-PDT or VEH-PDT on the upper extremities considered in-office time, side effects/adverse events (AEs), and duration of side effects/AEs to be acceptable.

Limitations. The majority of patients were male, and no statistical comparisons were conducted.

Conclusion. Patients were generally satisfied with ALA-PDT for the treatment of AKs of the face, scalp, and upper extremities and considered ALA-PDT to be equal to or more acceptable than previous treatments.

Trial registry information. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01475955; NCT02239679; NCT02137785.

Keywords: Photodynamic therapy, treatment satisfaction, actinic keratoses, aminolevulinic acid, acceptability

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are precancerous, dysplastic, epidermal lesions that can occur in individuals with chronic sun exposure, especially those with fair skin. Generally, AKs are found on sun-exposed areas (e.g., face, scalp, forearms, and backs of hands) and are recognized as scaly, rough lesions that can disappear and reappear over a period of months or years.1 In one study, the risk of progression of AKs to primary squamous cell carcinoma was 0.6 percent at one year and 2.6 percent at four years.2 Additionally, 65 percent of all primary squamous cell carcinomas identified in the study arose in lesions that were originally diagnosed as AKs.2

Aminolevulinic acid 20% solution (ALA) with blue light photodynamic therapy (PDT) is indicated for the treatment of minimally to moderately thick AKs of the face, scalp, and upper extremities.3 In multiple randomized, vehicle (VEH)-controlled Phase II and III studies, ALA-PDT was superior to VEH-PDT in the treatment of AKs.1,4,5 A Phase II study evaluating the effect of short incubation times and spot versus broad-area application of ALA-PDT in the treatment of AKs of the face or scalp (hereafter referred to as the short incubation study) found that short incubation ALA-PDT regimens were superior to VEH-PDT.1 Another Phase II study (hereafter referred to as the field cancerization study) reported that cryotherapy followed by ALA-PDT of the entire face was superior to cryotherapy with VEH-PDT for the proportion of patients with no facial AKs at study completion among patients at risk for field cancerization.4 In a Phase III study (hereafter referred to as the upper extremities study), ALA-PDT using a three-hour incubation with occlusion was superior to VEH-PDT for clearance of AKs of the upper extremities.5

The previous ALA-PDT studies also included top-level patient satisfaction and acceptability data.1,5 In the upper extremities study, 88 percent of patients treated with ALA-PDT reported being very or moderately satisfied with treatment response at their final study visit, compared with 42 percent of patients treated with VEH-PDT.5 Similarly, 79 percent of patients who received ALA-PDT in the short incubation study reported moderate or excellent improvement from baseline in the appearance of the treatment area, compared with 35 percent of patients who received VEH-PDT.1

In this study, we report detailed patient satisfaction data for ALA-PDT versus VEH-PDT, as well as patient-reported acceptability of ALA-PDT compared to previous treatments, in the short incubation, field cancerization, and upper extremities studies of ALA-PDT for the treatment of AKs.

Methods

Study design and patients. The short incubation, field cancerization, and upper extremities studies were previously described in full.1,4,5 Briefly, the short incubation study was a Phase II, randomized, evaluator-blinded, multicenter, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group study conducted in the United States (US; NCT01475955).1 Patients aged 18 years or older with 6 to 20 Grade 1 to 2 AK lesions on the scalp or face were randomized 1:1:1:1:1 to one of five treatment groups: broad application of ALA to the face or scalp one (ALA-BA1), two (ALA-BA2), or three (ALA-BA3) hours prior to blue light treatment; spot treatment of ALA to facial or scalp lesions two hours prior to blue light treatment (ALA-SP2); or broad application of VEH to the face or scalp one, two, or three hours prior to blue light treatment or spot treatment two hours prior to blue light treatment (VEH-PDT). Only one treatment area of interest was treated during the study. Blue light treatment was administered for 16 minutes and 40 seconds for a total delivered dose of 10 J/cm2. Patients had posttreatment follow-up assessments 24 to 48 hours after each treatment and two, four, eight, 12, and 24 weeks after initial PDT.

The field cancerization study was a Phase II, randomized, parallel-group, evaluator-blinded, VEH-controlled study conducted at 10 sites in the US (NCT02239679).4 Patients aged 18 years or older with 4 to 15 Grade 1 to 3 AK lesions on the face were included. At screening, patients with facial AKs and previously treated nonmelanoma skin cancer underwent cryotherapy with biopsy of adjacent clinically normal photodamaged skin. High-risk patients (those with histologically confirmed abnormal epidermal architecture with satellite atypical keratinocytes) were enrolled after 2 to 4 weeks and randomized 1:1:1 to receive two (ALA-2×) or three (ALA-3×) treatments with ALA or VEH (VEH-PDT) applied to the entire face for one hour, followed by blue light administration as described for the short incubation study. Patients had posttreatment follow-up assessments 24 hours and four, 12, 24, 36, and 52 weeks after initial PDT.

The upper extremities study was a Phase III, randomized, evaluator-blinded, VEH-controlled, parallel-group study conducted at 14 sites in the US (NCT02137785).5 Patients aged 18 years or older with 4 to 15 Grade 1 to 2 AK lesions on one or more upper extremity treatment area (i.e., area between the elbow and base of the fingers) were randomized 1:1 to receive ALA-PDT or VEH-PDT, followed by a three-hour incubation with occlusion; blue light treatment was administered as described for the short incubation and field cancerization studies. Treatment was repeated at Week 8 if any lesions were present within the treatment area, and patients were followed up at 24 hours and two, four, eight, and 12 weeks after initial PDT.

Assessments. Patient acceptance in the short incubation study was assessed via questionnaire at Week 24. Treatment-related improvement of skin lesions was graded on a scale of 0 (no improvement or worsening; not satisfied at all) to 3 (excellent improvement; very satisfied). Acceptability compared to prior treatments was graded on a scale of 1 (study treatment is more acceptable than prior treatment) to 3 (prior treatment is more acceptable than study treatment). In the field cancerization study, patient satisfaction was assessed by questionnaire at Week 52. Treatment satisfaction and acceptability were scored using the same scales as described for the short incubation study. In the upper extremities study, patient acceptance was assessed by questionnaire at Week 12. Treatment satisfaction was scored using the same scale as described for the short incubation and field cancerization studies. Acceptability of in-office time, side effects/adverse events (AEs), and duration of side effects/AEs for ALA-PDT were scored from 1 (agree totally) to 5 (do not agree at all). Acceptability compared to prior treatment was scored using the same scale as described for the short incubation and field cancerization studies.

Statistical analysis. No formal hypothesis testing was performed for any of the studies. Data are presented descriptively as the percentage of patients who gave each response.

Results

Patients. Baseline demographics and patient characteristics for the three studies were previously reported.1,4,5 In the short incubation study, 234 patients were enrolled, of whom 47, 48, 47, 46, and 46 were randomized to ALA-BA1, ALA-BA2, ALA-BA3, ALA-SP2, and VEH-PDT, respectively. All enrolled patients were White, the majority (211/234 [90%]) were male, and mean age was 68 years. Nearly all patients (98%) completed the study. In the field cancerization study, 166 patients were enrolled, of whom 53, 59, and 54 were randomized to ALA-2×, ALA-3×, and VEH-PDT, respectively. All patients were White, the majority (135/166 [81%]) were male, and mean age was 67 years. Ninety-six percent of patients (159/166) completed the study. Finally, in the upper extremities study, 269 patients were enrolled, of whom 135 and 134 were randomized to ALA-PDT and VEH-PDT, respectively. All patients were White, the majority (188/269 [70%]) were male, and mean age was 68 years. Ninety-seven percent of patients (262/269) completed the study.

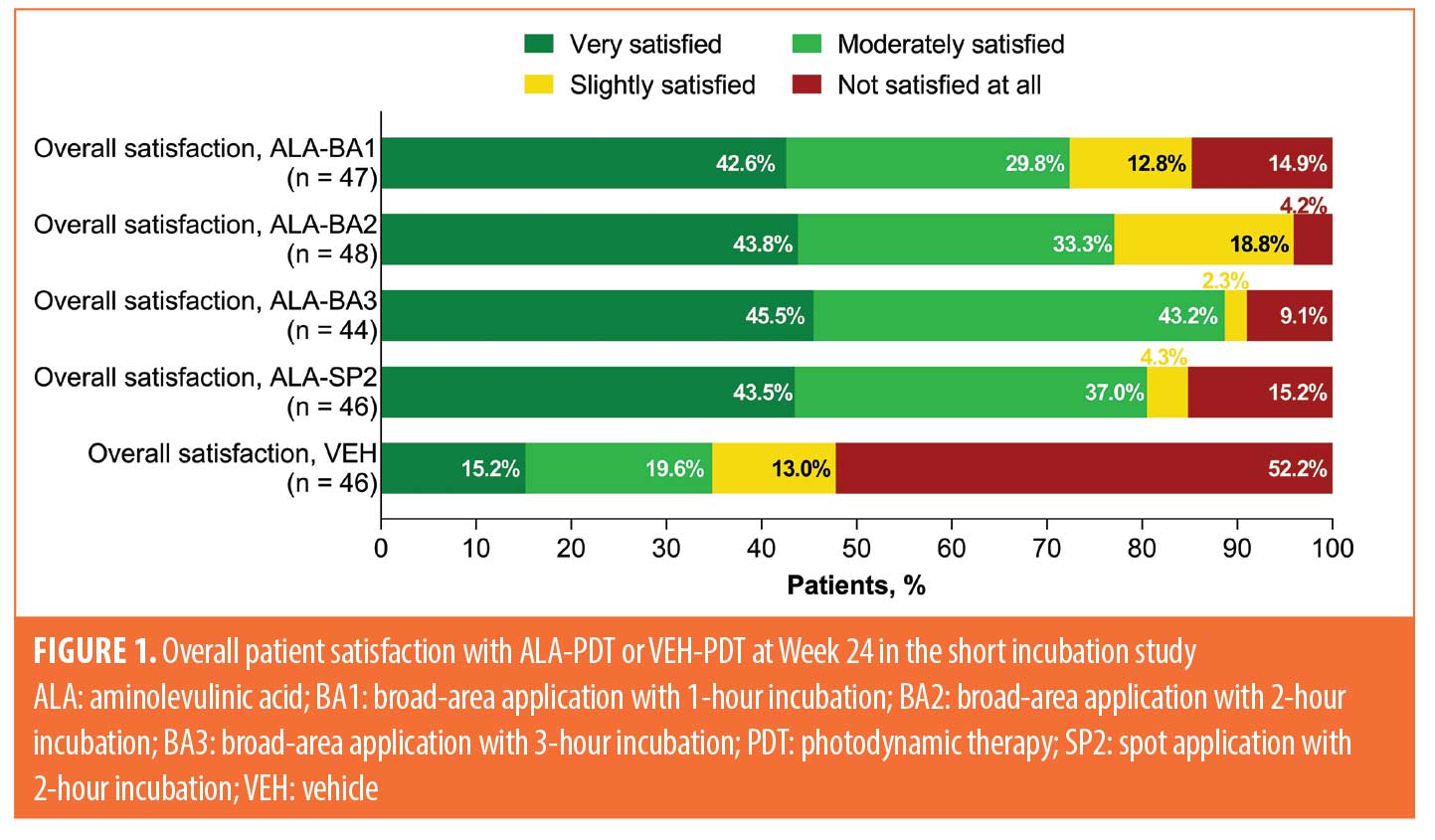

Overall treatment satisfaction (all studies). Treatment satisfaction for patients in the short incubation study (assessed at Week 24), field cancerization study (assessed at Week 52), and upper extremities study (assessed at Week 12) is shown in Figures 1 to 3. In the short incubation study, 81 of 185 patients (44%) who received any ALA-PDT treatment were very satisfied with their treatment response, compared to seven of 46 patients (15%) treated with VEH-PDT (Figure 1). A higher proportion of patients receiving ALA-PDT treatment were moderately satisfied with their treatment response (66/185 [36%]) versus VEH-PDT (9/46 [20%]). Patients receiving ALA-PDT treatment were less likely to report being unsatisfied with their treatment response (20/185 [11%]), compared to patients treated with VEH-PDT (24/46 [52%]).

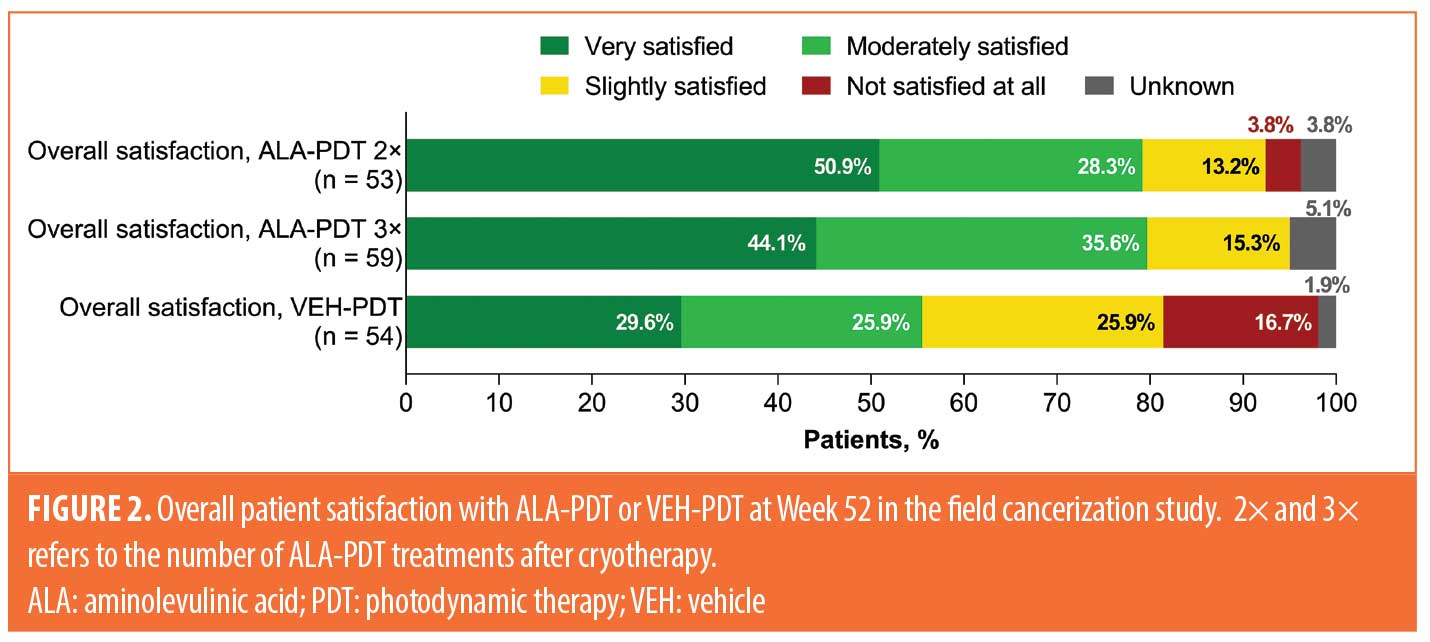

Among patients with satisfaction data in the field cancerization study, 89 of 112 (79%) who received any ALA-PDT regimen, compared to 30 of 54 (56%) who received VEH-PDT, were very or moderately satisfied with treatment (Figure 2). Patients who received two applications of ALA-PDT after cryotherapy reported similar satisfaction scores as patients who received three applications of ALA-PDT, whereas patients receiving VEH-PDT were more likely to report being slightly satisfied or not satisfied at all with treatment.

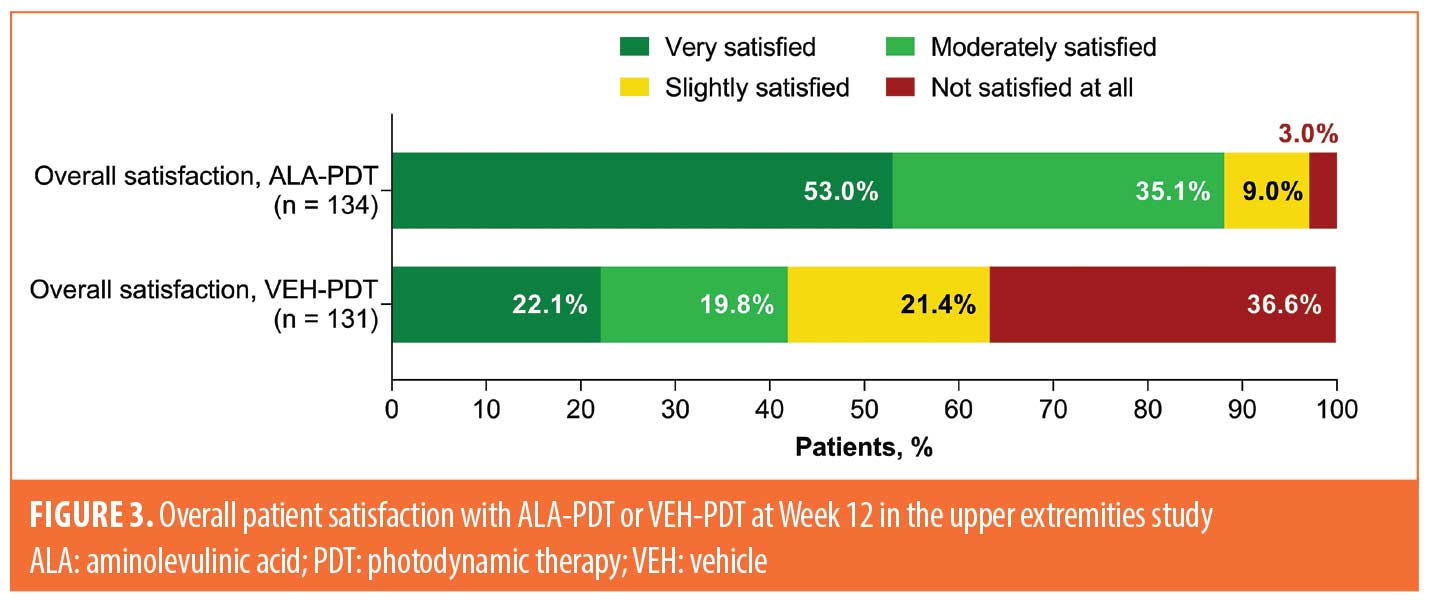

Among patients receiving ALA-PDT in the upper extremities study, 71 of 134 (53%) and 47 of 134 (35%) were very or moderately satisfied with their treatment, respectively, compared to 29 of 131 (22%) and 26 of 131 (20%) patients who received VEH-PDT, respectively (Figure 3).

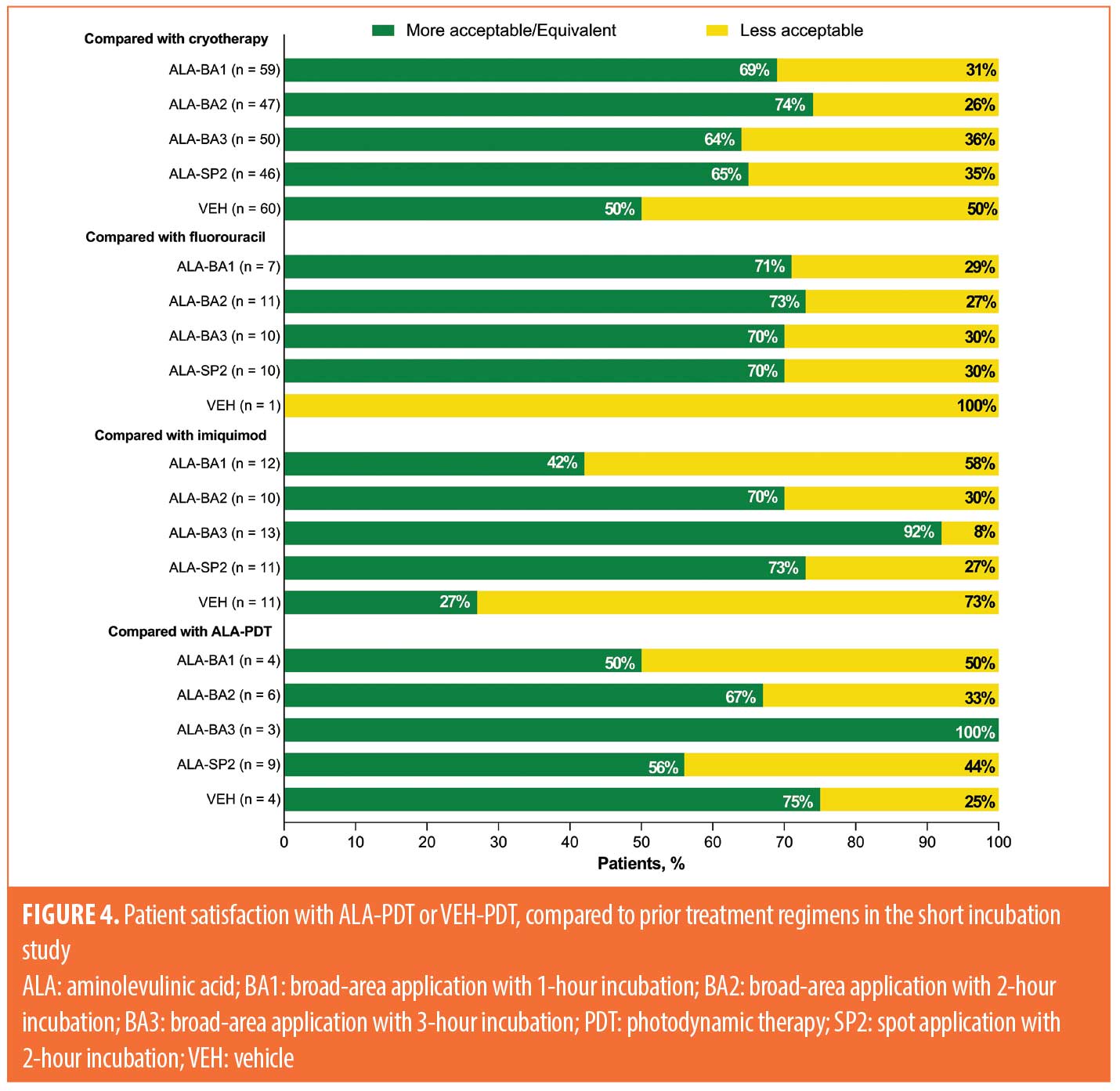

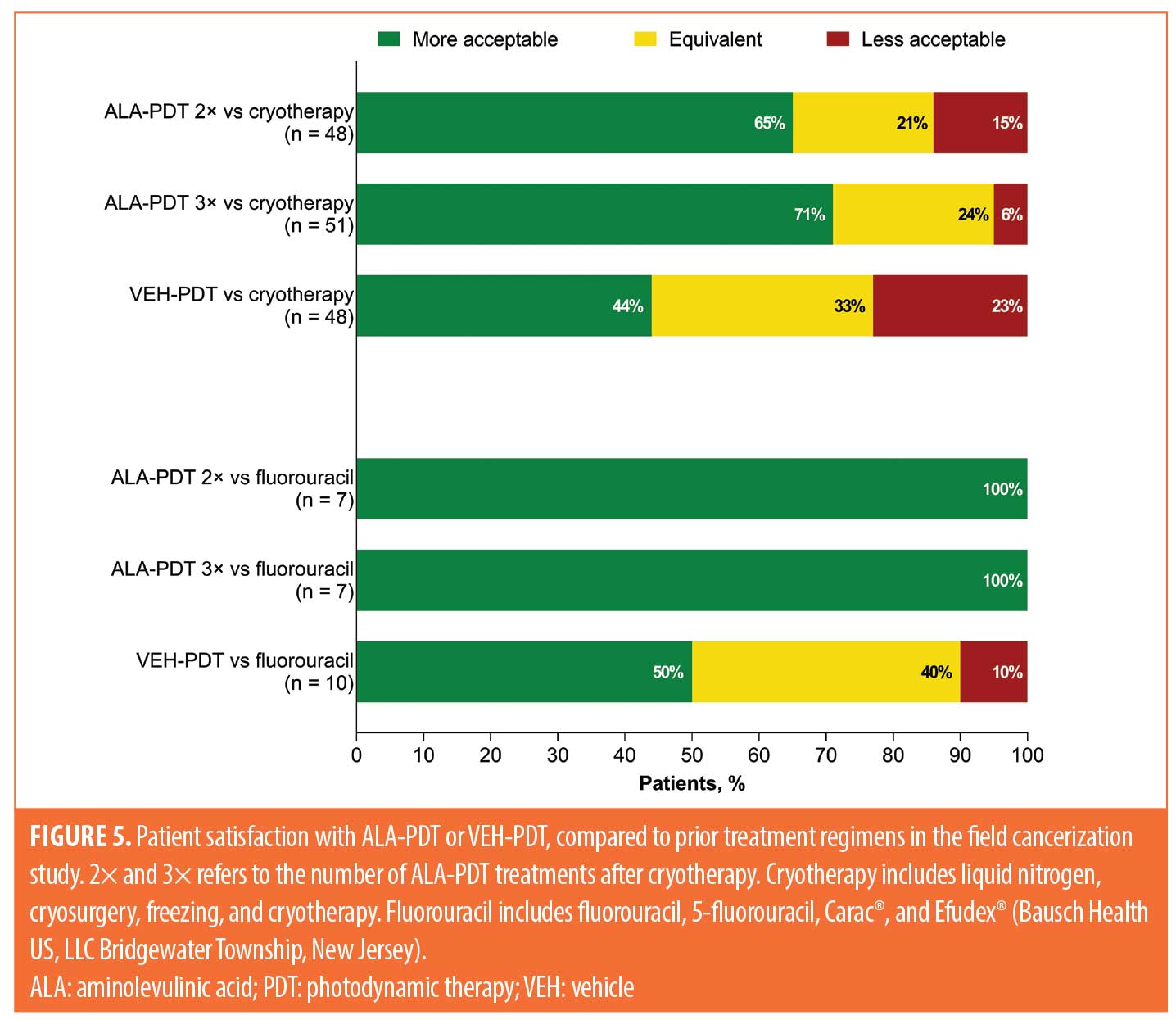

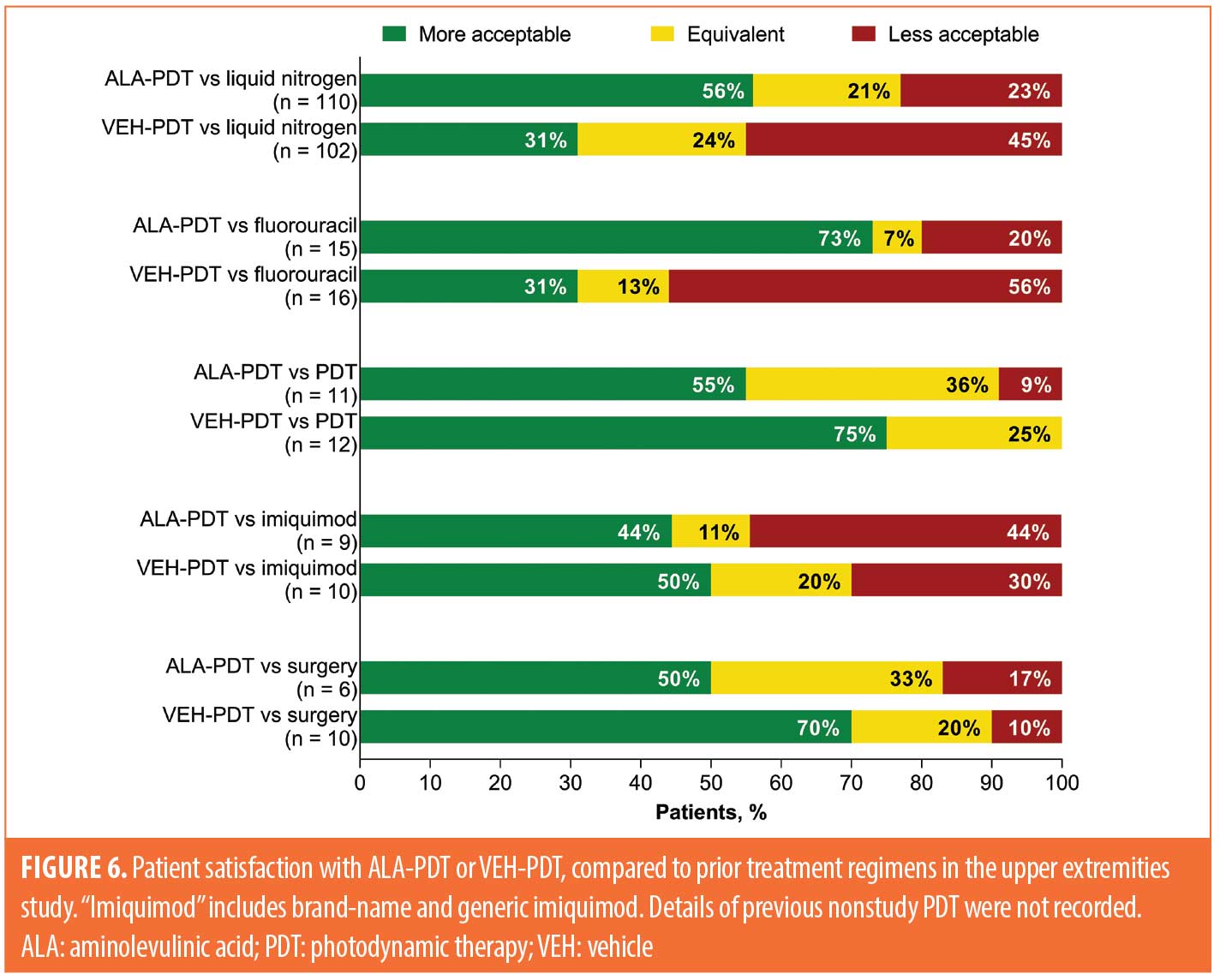

Acceptability of ALA-PDT and VEH-PDT compared to prior treatment. Acceptability of treatment compared to prior therapies for the three studies is shown in Figures 4 to 6. Data for the short incubation study at Week 24 show that the majority of patients receiving any ALA-PDT regimen considered it equally or more acceptable, compared to prior cryotherapy, as did 50 percent of patients receiving VEH-PDT (Figure 4). Greater proportions of patients receiving any ALA-PDT regimen, except ALA-BA1, reported it as equally or more acceptable than prior 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or imiquimod treatment. Although patient numbers were small, at least 50 percent of patients in each treatment arm considered the current study treatment to be equal to or more acceptable than prior ALA-PDT.

Field cancerization study data at Week 52 indicate that the majority of patients considered two applications of ALA-PDT to be more acceptable than cryotherapy (31/48 [65%]) and 5-FU (7/7 [100%]; Figure 5). Results were similar for patients receiving three applications of ALA-PDT, with 36 of 51 patients (71%) reporting greater acceptability versus prior cryotherapy and seven of seven patients (100%) reporting greater acceptability versus prior 5-FU treatment. Only 21 of 48 (44%) and five of 10 (50%) patients considered VEH-PDT to be more acceptable than prior cryotherapy and 5-FU, respectively.

In the upper extremities study, data at Week 12 show that at least half of patients receiving ALA-PDT considered it to be more acceptable than prior cryotherapy (62/110 [56%]), 5-FU (11/15 [73%]), PDT (6/11 [55%]), or surgery (3/6 [50%]), whereas four of nine patients (44%) considered it to be more acceptable than imiquimod (Figure 6). Among patients who received VEH-PDT, 31 percent considered prior cryotherapy (32/102) or 5-FU (5/16) to be more acceptable, whereas 75 percent (9/12), 50 percent (5/10), and 70 percent (7/10) reported that VEH-PDT was more acceptable than prior PDT, imiquimod, and surgery, respectively.

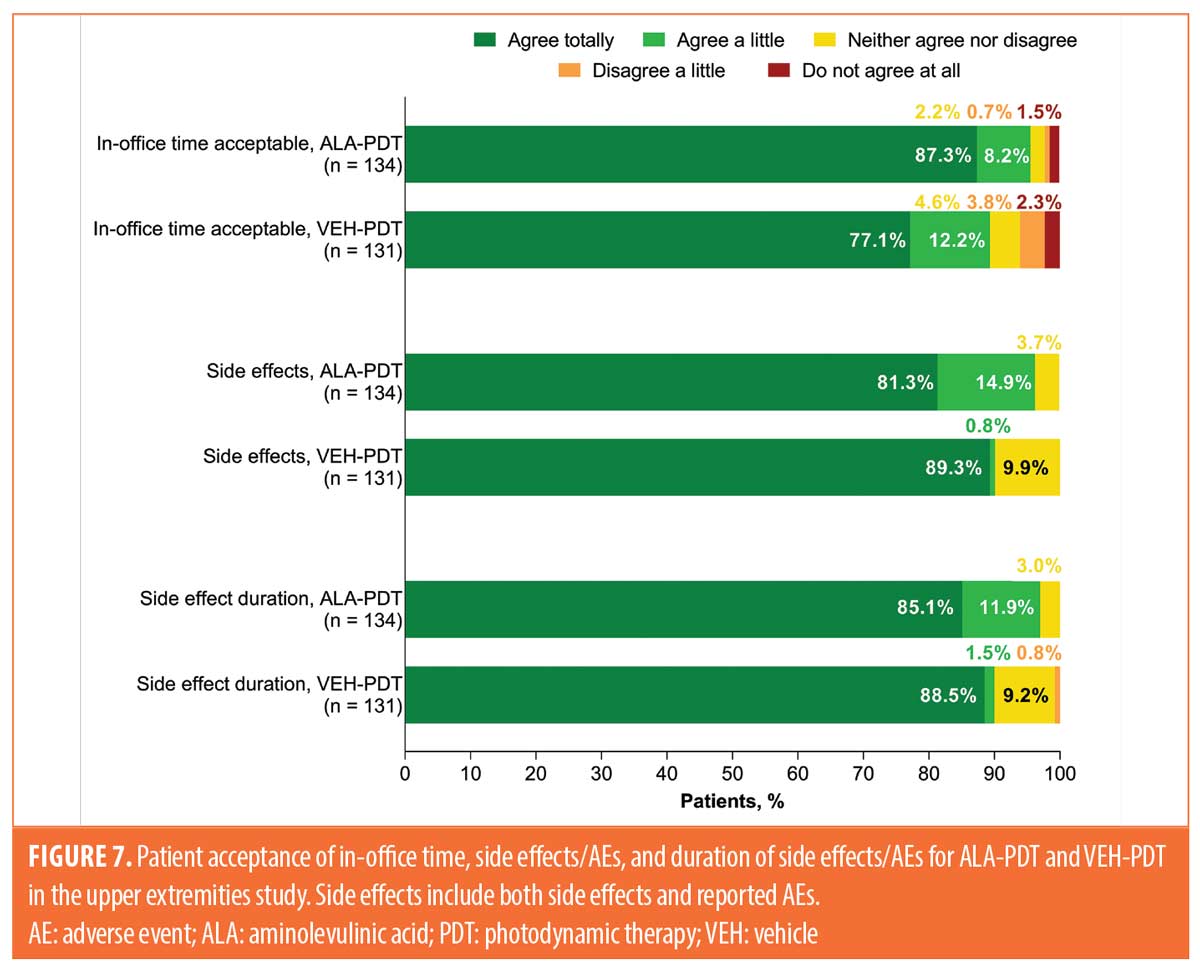

Patient acceptance of in-office time, side effects/AEs, and duration of side effects/AEs. In the upper extremities study, patient acceptance of in-office time, side effects/AEs, and duration of side effects/AEs were also assessed separately. The proportions of patients receiving ALA-PDT and VEH-PDT who responded “agree totally” to acceptability were 87 and 77 percent for in-office time, 81 and 89 percent for side effects/AEs, and 85 and 89 percent for duration of side effects/AEs, respectively (Figure 7).

Discussion

Detailed treatment satisfaction data for ALA-PDT from these three studies suggest that the majority of patients treated with ALA-PDT on the face, scalp, or upper extremities were very or moderately satisfied with treatment, and more patients treated with ALA-PDT were very or moderately satisfied, compared to those treated with VEH-PDT. Patients also generally considered ALA-PDT to be equivalent to or more acceptable than prior treatment modalities, including cryotherapy, 5-FU, imiquimod, PDT, and surgery. Additionally, similar proportions of patients receiving ALA-PDT or VEH-PDT on the upper extremities considered in-office time, side effects/AEs, and duration of side effects/AEs to be acceptable.

Patient satisfaction and quality of life (QoL) are sometimes used interchangeably in studies that assess treatment of AKs.6 Many factors can affect patient satisfaction, including patient demographics, lesion location, duration of therapy, AEs, tolerance, efficacy of treatment, and cost.6 Since treatment of AKs can be associated with discomfort, inconvenience, and impact on cosmetic appearance,6,7 patient satisfaction/QoL can be considered to be a balance between treatment outcomes and tolerability.6,8 Although patient satisfaction data reported for AK therapies are limited, published data appear to suggest that patients prefer PDT to some other therapies, due in part to its relatively lower negative impact on QoL.6,9–12 This appears to be consistent with patients in the three studies included in the current analysis, who generally preferred ALA-PDT to prior therapies.

Limitations. One limitation is that the patients in all three studies were overwhelmingly male, perhaps limiting generalization of the results to female patients. This discrepancy might be at least partially attributable to the fact that AKs tend to be more prevalent in men, which is potentially related to greater lifetime sun exposure and lack of photoprotection. Another limitation is that no statistical comparisons were conducted, with presented data being analyzed descriptively. Finally, differences in study design among the three studies complicated interpretation of the collective results. The International Dermatology Outcome Measures 2021 report had important updates from the AK workgroup on the development of an 11-item treatment satisfaction instrument to better reflect the features of AKs and the properties of available treatments. Once finalized and validated, this instrument is expected to effectively translate captured patient satisfaction responses into real-world use.13

Conclusion

The majority of patients treated with ALA-PDT in the three studies included in this report were very or moderately satisfied with treatment. Satisfaction was greater for patients treated with ALA-PDT, compared to those treated with VEH-PDT over multiple areas of the body (face, scalp, and upper extremities) with various incubation times, including high-risk patients after cryotherapy. ALA-PDT was equivalent to or more acceptable than multiple prior treatment modalities, including 5-FU, cryotherapy, and previous PDT. Taken together, these findings suggest that the majority of patients were satisfied with ALA-PDT for treatment of AKs of the face, scalp, and upper extremities and considered it to be equally or more acceptable, compared to previous treatments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients for their participation in the clinical studies. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Nitish Chaudhari, PhD, of AlphaBioCom, a Red Nucleus company, and funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

References

- Pariser DM, Houlihan A, Ferdon MB, et al. Randomized vehicle-controlled study of short drug incubation aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses of the face or scalp. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(3):296–304.

- Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2523–2530.

- LEVULAN® KERASTICK® (aminolevulinic acid HCl) for topical solution, 20%. Full prescribing information. Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.; 2020.

- Piacquadio D, Houlihan A, Ferdon MB, et al. A randomized trial of broad area ALA-PDT for field cancerization mitigation in high-risk patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(5):452–458.

- Brian Jiang SI, Kempers S, Rich P, et al. A randomized, vehicle-controlled Phase 3 study of aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratoses on the upper extremities. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45(7):890–897.

- Khanna R, Bakshi A, Amir Y, Goldenberg G. Patient satisfaction and reported outcomes on the management of actinic keratosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:179–184.

- Augustin M, Tu JH, Knudsen KM, et al. Ingenol mebutate gel for actinic keratosis: the link between quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and clinical outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(5):816–821.

- Emilio J, Schwartz M, Feldman E, et al. Improved patient satisfaction using ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% for the treatment of facial actinic keratoses: a prospective pilot study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:89–93.

- Morton C, Campbell S, Gupta G, et al. Intraindividual, right-left comparison of topical methyl aminolaevulinate-photodynamic therapy and cryotherapy in subjects with actinic keratoses: a multicentre, randomized controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(5):1029–1036.

- Tierney EP, Eide MJ, Jacobsen G, Ozog D. Photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses: survey of patient perceptions of treatment satisfaction and outcomes. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10(2):81–86.

- Jubert-Esteve E, Del Pozo-Hernando LJ, Izquierdo-Herce N, et al. Quality of life and side effects in patients with actinic keratosis treated with ingenol mebutate: a pilot study. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(8):644–650.

- Serra-Guillen C, Nagore E, Hueso L, et al. A randomized comparative study of tolerance and satisfaction in the treatment of actinic keratosis of the face and scalp between 5% imiquimod cream and photodynamic therapy with methyl aminolaevulinate. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(2):429–433.

- Zagona-Prizio C, Yousif J, Grant C, et al. International Dermatology Outcome Measures (IDEOM): report from the 2021 Annual Meeting. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21(8):867–874.