J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(11):20–22

by Ritu Swali, MD, and Monica Lee, BS

by Ritu Swali, MD, and Monica Lee, BS

Dr. Swali is with the Department of Medicine at the University of California, Irvine in Irvine, California. Ms. Lee is with the School of Medicine at the University of California, Irvine in Irvine, California.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this study.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Dermatomyositis is a disease of inflammation and vasculopathy, characterized by proximal muscle weakness and classic cutaneous eruptions. Often, patients show signs of lung, esophageal, and cardiac involvement. Cardiac involvement in dermatomyositis and other inflammatory myosidities can result in conduction abnormalities, ventricular dysfunction, and hypertrophy. Some patients will become symptomatic from the sequelae of the impairment, progressing to the onset of heart failure, pericarditis, or arrhythmias. Others might remain clinically asymptomatic, with evidence of cardiac involvement of their disease seen only with electrocardiograms and imaging. A preexisting damaged myocardium is more susceptible to the damaging effects of the chemical mediators and the stress of an anaphylactic reaction. Patients with dermatomyositis often have subclinical manifestations of cardiac involvement that can predispose them to more severe and life-threatening consequences of anaphylaxis and anaphylactoid reactions. The present case report documents a patient with dermatomyositis whose disease was not complicated with cardiac involvement yet who ultimately showed lasting cardiovascular effects from an anaphylactoid reaction. This case highlights the dangers of allergic reactions in patients with inflammatory myopathies, such as dermatomyositis, as they can have more profound cardiovascular manifestations of the reactions and develop enduring changes to their myocardium.

KEYWORDS: Anaphylaxis, dermatomyositis, electrocardiogram, myocarditis, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole

Dermatomyositis is a disease of inflammation and vasculopathy, characterized by proximal muscle weakness and classic cutaneous eruptions. Often, patients show signs of lung, esophageal, and cardiac involvement. Myocarditis with subclinical manifestations of arrhythmia, conduction abnormalities, and congestive heart failure are commonly encountered aberrations.1 Patients have a three-fold higher risk for myocardial infarction compared to the general population.2 Anaphylactoid reactions that go unrecognized for prolonged durations can induce systemic involvement. We present a case of dermatomyositis and anaphylaxis with persistent electrocardiogram changes.

Case Presentation

A 19-year-old man, with no significant past medical history, presented from his primary care physician’s clinic to the hospital with a rash, fever, and hypotension. Two days prior, he was discharged on high dose prednisone for newly diagnosed dermatomyositis (elevated antiribonucleoprotein and magnetic resonance imaging with lower extremity proximal muscle edema and skin biopsy showing interface dermatitis consistent with dermatomyositis) and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis.

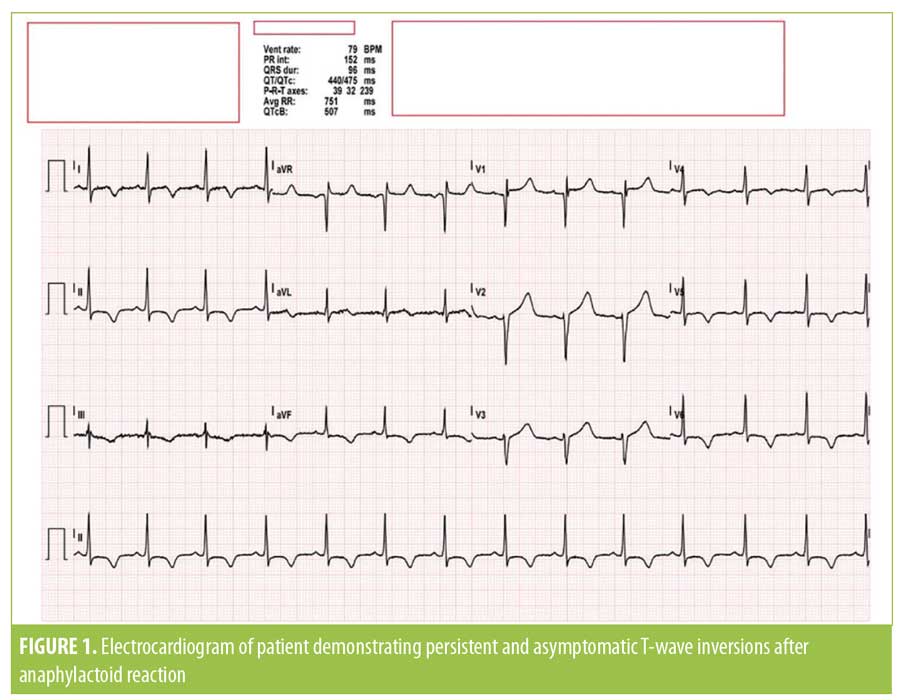

Upon arrival to the emergency department, he was febrile to 101.4°F, his blood pressure was 78/42mmHg, and his heart rate was in the 120-bpm range. His examination results were significant for nonblanchable, erythematous, reticular patches that had spread from his chest and abdomen to the bilateral upper and lower extremities together with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation plaques on the cheeks, chest, and extremities—likely from resolving dermatomyositis. Electrocardiography was notable for sinus tachycardia and new T-wave inversions in leads I, II, III, aVF, and V3 through V6. The patient’s brain natriuretic protein, lactic acid dehydrogenase, and creatine phosphokinase levels were mildly elevated, while his cortisol, lactate, tryptase, and procalcitonin levels were within the normal limits. Although the patient did not report any symptoms of airway edema, he was immediately injected with epinephrine, then subsequently admitted to the medical intensive care unit for fluid resuscitation and pressors, with rapid improvement of vital signs and resolution of the reticular rash.

Despite the patient being asymptomatic, three repeat electrocardiograms persistently showed T-wave inversions during the course of two days, so a cardiac workup was initiated. The results of troponin analysis and computed tomography angiography imaging for pulmonary embolism were negative. Echocardiography showed an unchanged left ventricular systolic function of 57 percent and trivial pericardial effusion without evidence of ventricular hypertrophy. The patient was discharged on prednisone 60mg daily and atovaquone 1,500mg for pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis, with plans made for the initiation of azathioprine as a steroid-sparing agent for dermatomyositis.

Discussion

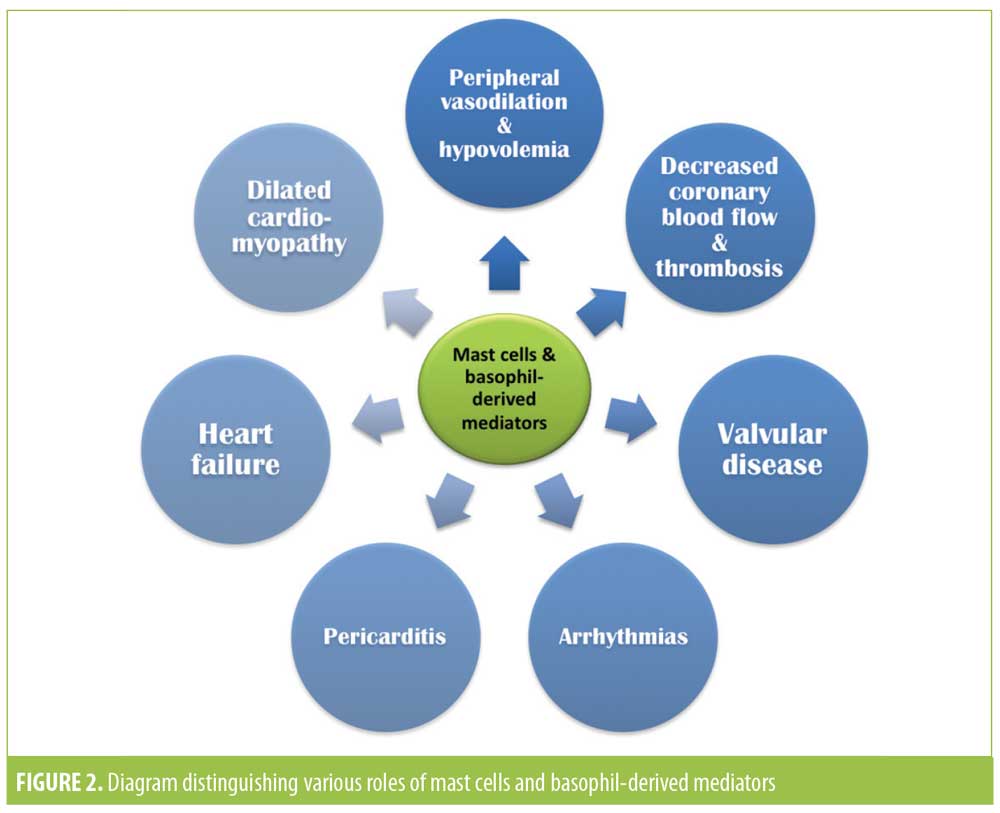

The early manifestation of anaphylaxis and anaphylactoid reactions is the involvement of the skin, respiratory, and gastrointestinal system. Patients can display rashes, urticaria, angioedema, laryngeal edema, bronchospasm, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea.1 However, the chemical mediators responsible for the peripheral manifestations of anaphylaxis are also implicated in the central effects on the heart, making it a target organ for allergic reactions. Older studies in healthy adults showed a cardiac impact from both direct chemical mediators acting on the heart and as a consequence of peripheral hypotension. Initial tachycardia and increased contractility were followed by myocardial depression due to systemic myocardial ischemia and the local effects of mediators on coronary perfusion and contractility.2 Newer studies have elucidated the presumed pathogenesis of mast cells and basophil-derived mediators, such as histamine, tryptase, chymase, renin, prostanoids, leukotrienes, and platelet-activating factors, causing peripheral vasodilation, relative hypovolemia, decreased coronary blood flow, thrombosis, and arrhythmias.1 The heart itself has mast cells in its myocardial fibers, vasculature, and adventitia.3 Cardiac involvement of reactions can manifest as chest pain, hypotension, collapse, shock, loss of consciousness, tachycardia, arrhythmias, or sudden cardiac death.1 The life-threatening effect of anaphylaxis is multifold and must be considered in patients with underlying heart disease.

Cardiac involvement in dermatomyositis is a well-documented but often subclinical manifestation of the inflammatory myopathy. These patients can have abnormal electrocardiograms or echocardiograms indicating conduction abnormalities, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrial enlargement, or hyperkinetic left ventricular contractions.4,5 Patients can have elevated troponin and eventually progress to showing heart failure, valvular disease, pericarditis, and dilated cardiomyopathy.6 Cardiac involvement not only portends a poorer outcome in myositis patients, leading to a decreased 10-year survival rate and an increased risk for overall mortality, but can also increase the risk of severe cardiac involvement in anaphylaxis.7,8

While, to our knowledge, there have been no studies conducted investigating the direct relationship between dermatomyositis patients and anaphylaxis, patients with dilated cardiomyopathies have a markedly increased number of mast cells.1 Strain from an anaphylactic reaction on an impaired heart at baseline can also put patients at greater risk if their cardiac function is unable to compensate or withstand the effects of anaphylaxis. Furthermore, dermatomyositis patients with underlying conduction abnormalities or impaired contractility can experience life-threatening arrhythmias, hypotension, and shock during reactions.

The patient described in this case did not have any clinical cardiac manifestations of his dermatomyositis. Upon diagnosis, his vital signs were normal, he denied experiencing chest pain, and the electrocardiography findings were unremarkable. However, when the patient presented in anaphylactic shock, he was hypotensive with a persistently abnormal electrocardiogram. This case highlights the potential relationship between and the danger of cardiac involvement in inflammatory cardiomyopathies like dermatomyositis and anaphylaxis. Subclinical but significant cardiac involvement in dermatomyositis can predispose patients to more severe and perhaps long-term consequences of anaphylaxis. Impaired contractility, conduction, and the background increased inflammatory state attributed to the myopathy can make the heart more susceptible to the effects of anaphylaxis. Patients can be at higher risk for decreased perfusion, demand ischemia, tachycardia, and arrhythmias, leading to potentially life threatening consequences. Since dermatomyositis patients are at high risk for myocardial necrosis, strain to the heart during an acute but profound stressor event like anaphylaxis can also hasten tissue necrosis, leading to longstanding effects. In the described patient, the electrocardiogram changes persisted after his anaphylaxis were resolved.

The longstanding effects of cardiac involvement in dermatomyositis have been studied in cases of juvenile dermatomyositis. Since these children are at increased risk for presenting cardiovascular risk factors and diseases, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and lipid abnormalities, the initial review of body mass index, blood pressure, blood sugar, and lipid findings at diagnosis could assist in monitoring and optimizing the cardiovascular health of young patients with dermatomyositis.9 As cardiac involvement is one the leading causes of mortality in dermatomyositis, the surveillance and prevention of such risk factors should not only be routine, but essential in disease management.10 If there is evidence of cardiac dysfunction on echocardiogram or electrocardiogram, even without symptoms, a full cardiac workup should be undertaken at diagnosis.11 While no published studies have researched the permanent changes to the myocardium in dermatomyositis patients after anaphylaxis, such information could guide monitoring and treatment. To further delineate their relationship, investigations into how dermatomyositis-induced damage and remodeling of the myocardium and its proinflammatory state affect the risk, manifestation, and severity of allergic reactions are warranted as such would also improve clinical awareness and treatment of both processes.

References

- Triggiani M, Montagni M, Parente R, Ridolo E. Anaphylaxis and cardiovascular diseases: a dangerous liaison. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14(4):309–315.

- Raper RF, Fisher MM. Profound reversible myocardial depression after anaphylaxis. Lancet. 1988;1(8582):386–388.

- Marone G, Genovese A, Varricchi G, Granata F. Human heart as a shock organ in anaphylaxis. Allergo J Int. 2014;23(2):60–66.

- Zhang L, Wang GC, Ma L, Zu N. Cardiac involvement in adult polymyositis or dermatomyositis: a systematic review. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(11):686–691.

- Deveza LM, Miossi R, de Souza FH, et al. Electrocardiographic changes in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Rev Bras Reumatol Engl Ed. 2016;56(2):95–100.

- Sunderkötter C, Nast A, Worm M, et al. Guidelines on dermatomyositis—excerpt from the interdisciplinary S2k guidelines on myositis syndromes by the German Society of Neurology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14(3):321–338.

- Marie I. Morbidity and mortality in adult polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14(3):275–285.

- Van Gelder H, Charles-Schoeman C. The heart in inflammatory myopathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014;40(1):1–10.

- Silverberg JI, Kwa L, Kwa MC, Laumann AE, Ardalan K. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular comorbidities of juvenile dermatomyositis in US children: an analysis of the National Inpatient Sample. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(4): 694–702.

- Jayakumar D, Zhang R, Wasserman A, Ash J. Cardiac manifestations in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: an overview. Cardiol Rev. 2019;27(3):131–137.

- Cantez S, Gross GJ, MacLusky I, Feldman BM. Cardiac findings in children with juvenile dermatomyositis at disease presentation. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15(1):54.