J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(5):46–49.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(5):46–49.

by Safoura Shakoei, MD; Maryam Daneshpazhooh, MD; Maryam Nasimi, MD; and Shahin Hamzelou, MD

Drs. Shakoei and Hamzelou are with the Department of Dermatology at Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran. Drs. Daneshpazhooh and Nasimi are with the Department of Dermatology at Razi Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is an uncommon, life-threatening hypersensitivity drug reaction with a high mortality rate that involves the skin and mucous membranes. Most reported cases involving pregnant patients were seen in those with human immunodeficiency virus. Here, we discuss a 21-year-old Iranian woman who presented at 18 weeks’ gestation with extensive TEN following the administration of ondansetron with no any other risk factors.

Keywords: Ondansetron, pregnancy, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug-induced

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a severe, delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction characterized by epidermal necrosis with widespread separation of the epidermis and mucous membrane at the dermal-epidermal junction with a high mortality rate.1 The percentage of detachment is less than 10 percent in Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), higher than 30 percent in TEN, and 10 to 30 percent in the SJS/TEN overlap variant.2 The responsible factors are unidentified in 25 to 50 percent of cases, but, in 80 percent of patients, drugs have been mentioned as causative factors for this reaction.2

TEN/SJS can occur during pregnancy and is considered a challenging medical situation. Risk factors and outcomes of SJS/TEN in pregnancy are unknown relative to in the general population. The complex immunomodulatory responses in pregnancy might be a reason for SJS/TEN induction in patients without any known risk factors.3 TEN is associated with a high mortality rate and many treatments have been trialed.4

Here, we report a pregnant woman who developed TEN following the administration of ondansetron.

Case presentation

A 21-year-old Iranian woman presented to the hospital at 18 weeks’ gestation with a two-day history of a pruritic skin rash and mucous membrane lesions. Targetoid plaques with necrotic centers and vesicular lesions had involved the face and trunk, with a positive Nikolsky’s sign on the back. The lesions were associated with hemorrhagic crusts of the lips and painful erosions on the oral and genitalia mucosa. Laboratory tests showed only mild anemia (hemoglobin concentration of 11g/dL) and high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (69mm/hour). Other laboratory tests and immunoglobulin A were within normal ranges. Her temperature was 39°C (102.2°F).

Treatment with 20mg of prednisolone daily and topical clobetasol ointment was started. Four weeks before the appearance of the lesions, she had ingested 4mg of ondansetron twice daily for the treatment of nausea and vomiting. During the following 72 hours, the lesions extended on the extremities and erosive stomatitis, painful genital erosions, and mild bilateral conjunctivitis appeared. Flaccid bullae involved the trunk and extremities. By the third day of admission, the epidermis was detachable in more than one third of her body surface area. She was given a diagnosis of TEN on the basis of clinical findings and was transferred to the intensive care unit. The dose of prednisolone was increased to 60mg daily and 400mg of oral acyclovir three times daily was started and supportive care was provided. In addition, high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (120g) was administered for two days but was discontinued due to the presence of bicytopenia (white blood cell count of 2,600/L, hemoglobin concentration of 5.6g/dL, and platelet count of 155,000/L). Lactate dehydrogenase, Retic count, vitamin B12, folate, collagen vascular tests, viral markers, and liver function tests were normal. Fragmented red blood cells were not seen. The prednisolone was tapered slowly over three weeks. She gradually improved and total re-epithelialization of the lesions was achieved after three weeks.

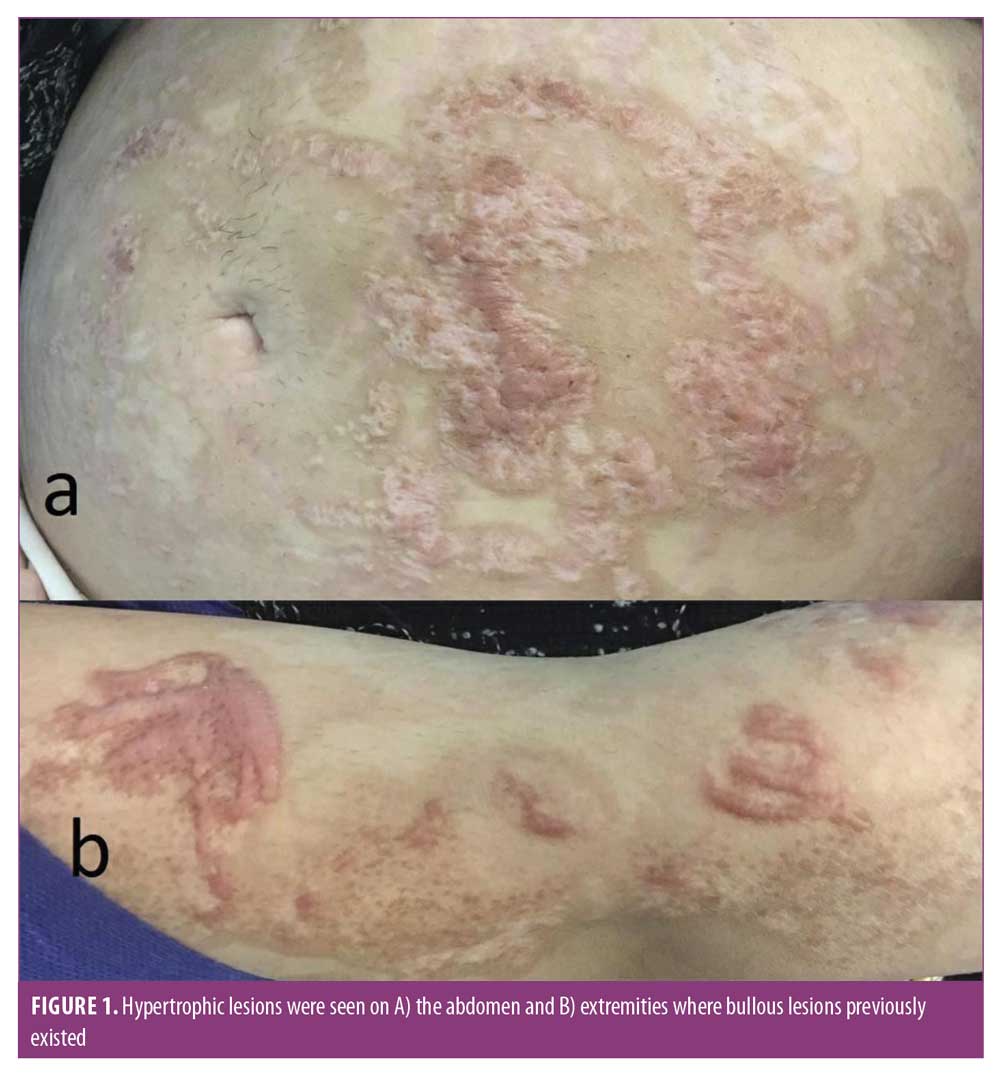

Hypertrophic scars were seen on the abdomen and extremities during her follow-up visit two months later (Figure 1). An uneventful vaginal delivery started at 38 weeks and three days of gestation following the rupture of membranes. The patient gave birth to a healthy baby girl (weight of 3,080g, length of 50cm, Apgar score: 8/10 at one minute and 10/10 at five minutes). She had no signs of TEN or sequelae resulting from treatment of her mother.

Discussion

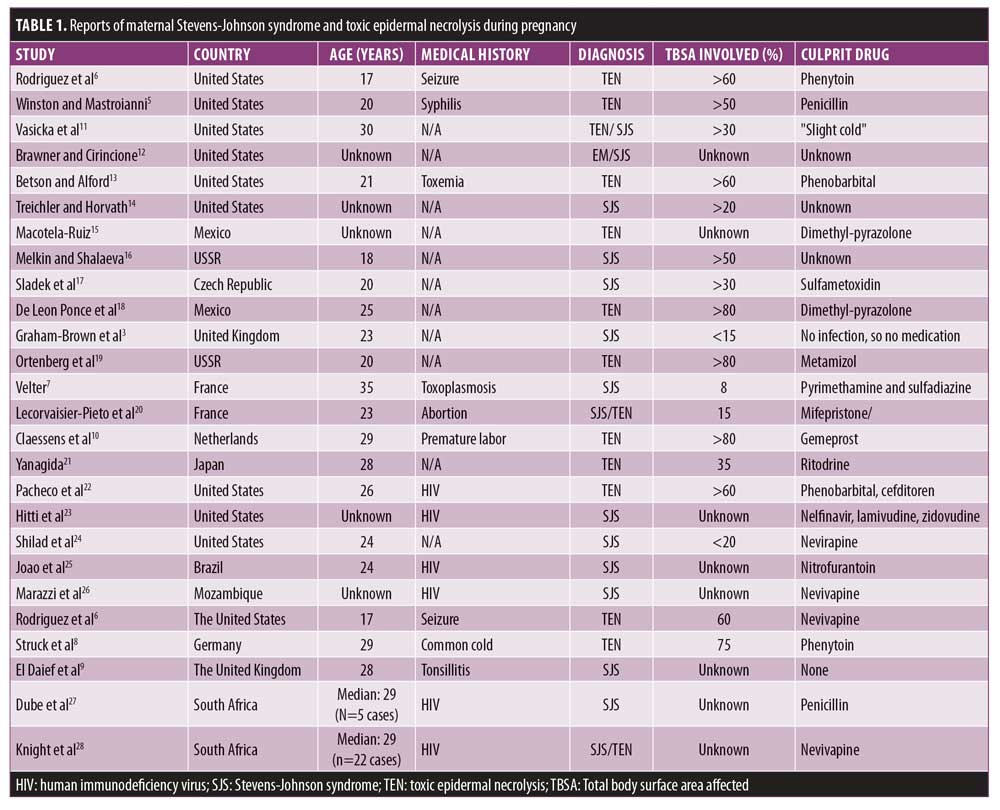

Although the occurrence of SJS in a pregnant woman was first reported in 1954,5 few other reports to date exist (Table 1). To the best of our knowledge, there is only one report where the mother and neonate were both affected by SJS lesions; the mother had taken phenytoin three weeks before the manifestation of the disease and the baby was born deceased via spontaneous delivery on Day 4 of the mother’s hospitalization.6 Three potential mechanisms have been offered for this event: 1) genetic factors that cause an inability of detoxification of the drugs, 2) the susceptibility of developing SJS due to specific human leukocyte antigens, and 3) the existence of drug-specific cytotoxic T-cells transferred from the mother’s circulation to the baby’s.6,7 However, similar to what happened in our case, no other report detailed involvement of the neonate, indicating that, in most situations, the causative factor does not cross over to the baby.7

Pregnancy is a unique physiological condition that might itself be a risk factor for SJS. The exact pathophysiology of this susceptibility is not clear, but it seems that the immune response is unique during pregnancy. It has been stated that SJS affects pregnant women at younger ages than nonpregnant patients. In addition to drugs, which are the most common causes of SJS, infections, such as upper respiratory infections or human immunodeficiency virus, as well as cancers have been postulated as contributing factors in pregnant or nonpregnant patients.8,9 Patients such as those who have received bone marrow transplants or those suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus are also at greater risk for SJS.10 To the best of our knowledge, our case was the first report of TEN as a result of ondansetron in pregnancy.

Conjunctival scarring and blindness are the most ominous complications seen in patients surviving TEN. In addition, necrolytic lesions of TEN can cause stenosis or synechiae of the vagina in almost two-thirds of affected women, and lesions such as introital adenosis can also develop. Vaginal strictures can obstruct the delivery canal, preventing normal delivery, and female patients with SJS in whom prophylactic procedures (e.g., putting petrolatum gauze in the canal) have not been considered during their treatment might not experience a natural pregnancy with effective vaginal delivery.9 Fortunately, our patient had a normal delivery and no complicated strictures because she did not have necrolytic lesions inside the vagina, instead remaining limited to the labias and introitus.

Minor long-term complications for this patient included hypertrophic scars and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; these side effects are common in these patients.9

Conclusion

In conclusion, pregnancy might induce SJS or TEN due to immunologic changes8 but, fortunately, in most cases, the fetus is not affected. Complications can cause obstruction of the delivery canal and require prophylactic interventions, such as putting petrolatum gauzes into the canal. Here, we have reported the case of a pregnant woman with TEN, possibly attributed to ondansetron therapy, who successfully delivered a normal female baby via normal vaginal delivery.

References

- Maverakis E, Wang EA, Shinkai K, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis standard reporting and evaluation guidelines: results of a National Institutes of Health Working Group. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(6):587–592.

- Medeiros MP, Carvalho CHC. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis—retrospective review of cases in a high complexity hospital in Brazil. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(2):191–196.

- Graham-Brown RA, Cochrane GW, Swinhoe JR, et al. Vaginal stenosis due to bullous erythema multiforme (Stevens–Johnson syndrome). Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1981;88(11):1156–1157.

- Kinoshita Y, Saeki H. A review of the active treatments for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Nippon Med Sch. 2017;84(3):110–117.

- Winston HG, Mastroianni L, Jr. Stevens–Johnson syndrome in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;67(3):673–676.

- Rodriguez G, Trent JT, Mirzabeigi M, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a mother and fetus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 Suppl): S96–S98.

- Velter C, Hotz C, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome during pregnancy: case report of a newborn treated with the culprit drug. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(2):224–225.

- Struck MF, Illert T, Liss Y, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31(5):816–821.

- El Daief SG, Das S, Ekekwe G, Nwosu EC. A successful pregnancy outcome after Stevens–Johnson syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34(5):445–446.

- Claessens N, Delbeke L, Lambert J, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with treatment for preterm labor. Dermatology. 1998;196(4):461–462

- Vasicka AI, Lin TJ, Das BK. Erythema multiforme exudativum (Stevens–Johnson syndrome) at term pregnancy: report of one case. Obstet Gynecol. 1958;12(2):225–229.

- Brawner D, Cirincione VJ. Erythema multiforme; a case report with a review of the literature of the past five years. J Med Assoc Ga. 1959;48(5):224–225.

- Betson JR AC. Stevens–Johnson syndrome secondary to phenobarbital administration in the treatment of toxaemia of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1961;18:195–199.

- Treichler HP, Horvath PN. Erythema multiforme exudativum (Stevens–Johnson syndrome) in early pregnancy: report of a case. Obstet Gynecol. 1964;24:309–312.

- Macotela-Ruiz E. Syndrome de Lyell. Chez une femme enccinte de quatres mois. Med Hyg (Geneve). 1974:302.

- Mel’kin KF, Shalaeva NV. [Severe form of exudative erythema multiforme in pregnancy (Stevens–Johnson syndrome)]. Akush Ginekol (Mosk). 1974(5):71–72. Article in Russian.

- Sladek M, Horacek J, Martincik J, Micanek B. [Stevens–Jonson’s disease treated by corticoids in pregnancy (author’s transl)]. Cesk Gynekol. 1976;41(4):254–255. Article in Czech.

- De Leon Ponce MD, Valencia MD, Lopez-Liera Mendez M, Rubio Lenares G. Therapeutic re-evaluation of toxic epidermal necrolysis in pregnancy. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 1976;39: 77–84.

- Ortenberg Ia A, Sandakova GS, Ortenberg GK. [Intensive therapy of Lyell’s disease in pregnancy]. Anesteziol Reanimatol. 1987(5):68–69. Article in Russian.

- Lecorvaisier-Pieto C, Joly P, Thomine E, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after mifepristone/gemeprost-induced abortion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(1):112.

- Yanagida S. A case report of pregnancy associated with Stevens–Johnson syndrome at 16 weeks of gestation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Japon. 2002;52:943–947.

- Pacheco H, Araujo T, Kerdel F. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a pregnant, HIV-infected woman. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41(9):600–601.

- Hitti J, Frenkel LM, Stek AM, et al. Maternal toxicity with continuous nevirapine in pregnancy: results from PACTG 1022. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(3):772–776.

- Shilad A, Predanic M, Perni SC, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus, pregnancy, and Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 2):1254–1256.

- Joao EC, Calvet GA, Menezes JA, et al. Nevirapine toxicity in a cohort of HIV-1-infected pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(1):199–202.

- Marazzi MC, Germano P, Liotta G, et al. Safety of nevirapine-containing antiretroviral triple therapy regimens to prevent vertical transmission in an African cohort of HIV-1-infected pregnant women. HIV Med. 2006;7(5):338–344.

- Dube N, Adewusi E, Summers R. Risk of nevirapine-associated Stevens–Johnson syndrome among HIV-infected pregnant women: the Medunsa National Pharmacovigilance Centre, 2007–2012. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(5):322–325.

- Knight L, Todd G, Muloiwa R, et al. Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: maternal and foetal outcomes in twenty-two consecutive pregnant HIV infected women. PloS One. 2015;10(8):e0135501.