J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(9):E59–E65

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(9):E59–E65

by George Han, MD, PhD; Jashin J. Wu, MD; and James Q. Del Rosso, DO

Dr. Han is with the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York. Dr. Wu is with the Dermatology Research and Education Foundation in Irvine, California. Dr. Del Rosso is with JDR Dermatology Research/Thomas Dermatology in Las Vegas, Nevada.

FUNDING: This study was funded by Ortho Dermatologics.

DISCLOSURES: Dr. Han is or has been an investigator, consultant/advisor, or speaker for AbbVie, Athenex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bond Avillion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Janssen, LEO Pharma, MC2, Ortho Dermatologics, PellePharm, Pfizer, Regeron, Sanofi Genzyme, Sun Pharmaceuticals and UCB. Dr. Wu is or has been an investigator, consultant, or speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Bausch Health US, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Sun Pharmaceutical, UCB. Dr. Del Rosso has served as a consultant, investigator, and speaker for Ortho Dermatologics.

ABSTRACT: A concern with the increasing use of prescription drugs during pregnancy is teratogenic risk. This risk is undetermined for most drugs approved in the United States (US) from 2000 to 2010. Acne and psoriasis are chronic diseases that typically occur during the child-bearing years, and as topical retinoids are recommended for both acne and psoriasis treatment, is it possible for women to be exposed to a topical retinoid during pregnancy. Pharmacokinetic studies show relatively low systemic exposure from topical retinoids, but the exposure levels that could lead to teratogenicity in humans are unknown. Tazarotene, a topical retinoid, was US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for both acne and psoriasis using pharmacokinetic data from psoriasis studies, which estimated the data based on use of tazarotene on up to 20% body surface area. As such, under both the previous and current FDA pregnancy labeling, tazarotene is not recommended for use during pregnancy. The goal of this literature review was to provide historical context for the pregnancy labeling rule for tazarotene compared with other approved retinoids and gather available data on tazarotene- and retinoid-related pregnancy outcomes. While there are case reports of topical tretinoin and adapalene exposure in utero, it is unclear if either affected fetal development. In terms of topical tazarotene, there are currently limited data regarding pregnancy outcomes after in-utero exposure. Additional case reports and outcomes studies are needed to further explore the safety of topical tazarotene in pregnancy.

Keywords: Retinoids, tazarotene, topical, pregnancy, review, labeling

Tazarotene is a topical retinoid approved in the United States (US) for the treatment of acne and psoriasis,1–3 both chronic diseases that typically occur during the child-bearing years. While pharmacokinetic studies show relatively low systemic exposure from topical tazarotene,4,5 the levels that could lead to teratogenicity in humans are unknown.1,5 Tazarotene was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for both acne and psoriasis using pharmacokinetic data from psoriasis studies; these studies estimated the pharmacokinetic data based on the use of tazarotene on up to 20 percent of the body surface area, whereas the face accounts for only two percent of the body surface area.1,5 As such, under the previous FDA pregnancy labeling, topical tazarotene was contraindicated for use during pregnancy (Category X).5

The goal of this review is to provide the historical context for the pregnancy labeling rule for tazarotene compared with other approved retinoids and to briefly summarize the pharmacokinetics of topical retinoids as well as the available data on tazarotene- and retinoid-exposure and pregnancy outcomes.

Prescription Drug Use During Pregnancy

The use of prescription drugs during pregnancy has been increasing.6 According to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2006, 22 percent of pregnant women and 47 percent of non-pregnant women of childbearing age (15–44 years) reported using prescription medications in the past 30 days.7 Another study using data from two large registries found that 50 to 70 percent of women interviewed after delivery reported having taken at least one prescription medication while pregnant; in addition, 29 to 49 percent reported using these medications in the first trimester and the use of four or more medications (prescribed or over the counter) during the first trimester has tripled, from 9.9 percent to 27.6 percent.6

Use of medications during pregnancy is concerning, as some drugs could cause abnormal embryo or fetal development. Drugs with this potential are called teratogens.8 Whether a drug can exert teratogenic effects is dependent on the conditions of gestational exposure (e.g., timing, duration, frequency, drug dose, and the chemical characteristics of the drug).8 The task of determining efficacy, safety (including teratogenic potential), and dosing when prescribing medications to women who might become, or already are, pregnant is left to clinicians.9,10

FDA Drug Labeling and Classification

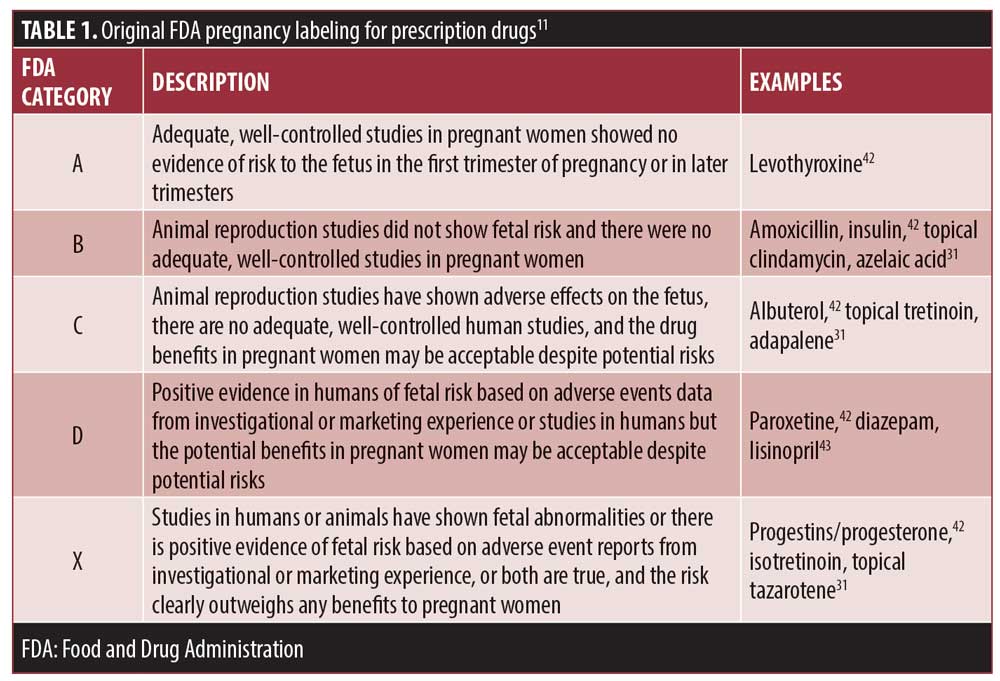

In 1979, the FDA implemented regulations for prescription drugs requiring a label summarizing available safety and efficacy information; part of these requirements included providing information regarding use during pregnancy, labor/delivery, and lactation.11 Unless a drug was known to not have any systemic absorption nor any potential for indirect fetal harm, it was required to be classified based on the risk of reproductive or developmental effects, whether the maternal benefits outweighed the possible risks to the fetus, and if experimental data were available from humans and/or animals.11 Drugs were categorized using one of five letters: A, B, C, D, or X (Table 1).11 Any drug in Category A was considered to have a low teratogenic potential and any drug Categorized as X was not recommended for use during pregnancy.

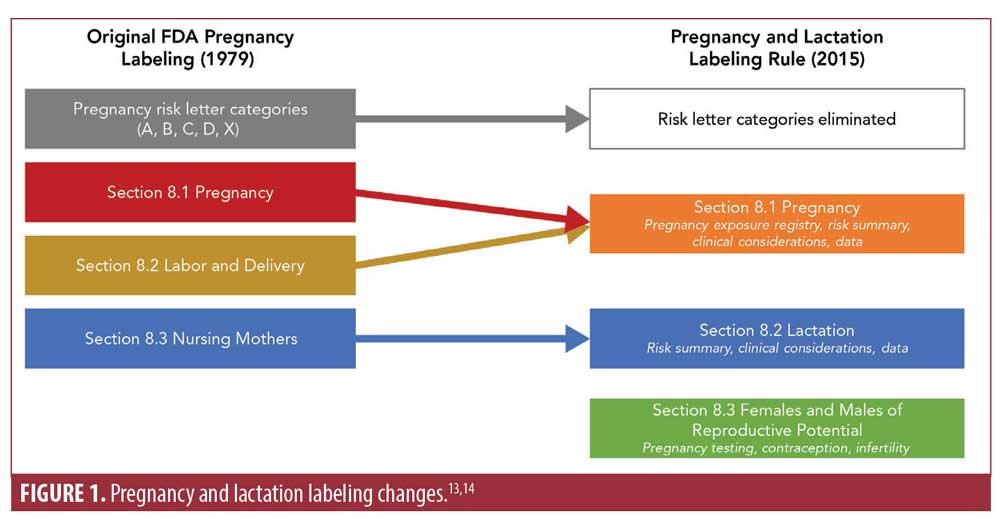

After the initial labeling requirements were developed, there were concerns that the labeling was unclear, with insufficient information about potential developmental risks and potential effects of drug discontinuation during pregnancy on the mother and/or fetus.9,12 Additional concerns included: the lack of information to assist clinicians in determining the relevance of data from animal studies; the appearance that different drugs in the same letter category had comparable risks and benefits when they did not; the appearance that inclusion into a category was based solely on risk; and the lack of procedures in place for updating the label if new safety data became available.9 In response to these concerns, the FDA changed the pregnancy labeling in 2014 now referred to as the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule. The letter categories were removed and the narrative subsections in the “Use in Specific Populations” section were revised (Figure 1); these subsections now include pregnancy (Section 8.1), lactation (Section 8.2), and a new section on females and males of reproductive potential (Section 8.3).13,14 Furthermore, labels are now required to be updated if new information causes the current label to be “inaccurate, false, or misleading”. These changes went into effect in June 2015.

While the label changes provide a more clinically relevant summary of the data, teratogenic risk is still undetermined for 98 percent of the drugs approved by the FDA between 2000 and 2010; furthermore, almost 75 percent of these drugs had no human data available regarding safety in pregnancy.15 This is due to the exclusion of pregnant women and those planning to become pregnant from clinical drug trials for ethical concerns.9,10 As such, potential teratogenic risks are determined primarily through preclinical toxicity studies in animals9,10 and post-marketing data from voluntary case reports and registries.10 Neither are ideal ways to determine teratogenic risk. Animal toxicity studies do not present clear information regarding teratogenic risks, as effects in animals are not necessarily predictive of the same effects in humans.16 Additionally, it can be difficult for clinicians to determine the relevance of animal data and interpretation may vary.9 Finally, teratogenic risk may not be determined for years or decades after human data from case reports and registries become available.10

Retinoids and Tazarotene

As noted previously, prescription medications are frequently used by women of reproductive age and during pregnancy. Acne vulgaris and psoriasis are both chronic, inflammatory skin diseases that typically occur during the reproductive years and can negatively impact quality of life.17,18 Acne is a common disease, occurring in 85 percent of adolescents in the US; it also currently affects up to 12 percent of adult women18 and prevalence in adults appears to be increasing. Psoriasis is less common, occurring in 2 to 3 percent of the global population, with an onset typically between the ages of 18 to 39 years.19

Topical treatments in the form of lotions, creams, gels, and foams provide localized drug delivery, which decreases systemic exposure;5,20 these are standard-of-care for treating mild-to-moderate disease.17,20 Topical retinoids are recommended for both acne and psoriasis treatment.17,18 Retinoids are vitamin A derivatives that vary in terms of efficacy and tolerability as a result of binding to different retinoic acid receptors.18 Four topical retinoids and one oral retinoid are FDA-approved for acne treatment: tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene, trifarotene, and oral isotretinoin.18,21,22 Tazarotene is also approved for the treatment of plaque psoriasis on up to 20 percent of body surface area.1,2,17 As retinoid use is limited by irritation, treatments are available in one or more dosages and formulations (i.e., gel, cream, foam, lotion).18,21 Studies have shown that topical tazarotene is safe and effective for the treatment of psoriasis (dosages: 0.1%; 0.01%; 0.05%; 0.045%)23–25 and acne (0.1%; 0.045%).26–30 As acne is a very common disease in women of child-bearing age and topical retinoids are a typical treatment, it is possible for women to be exposed to a topical retinoid during pregnancy.

Tazarotene Pregnancy Labeling

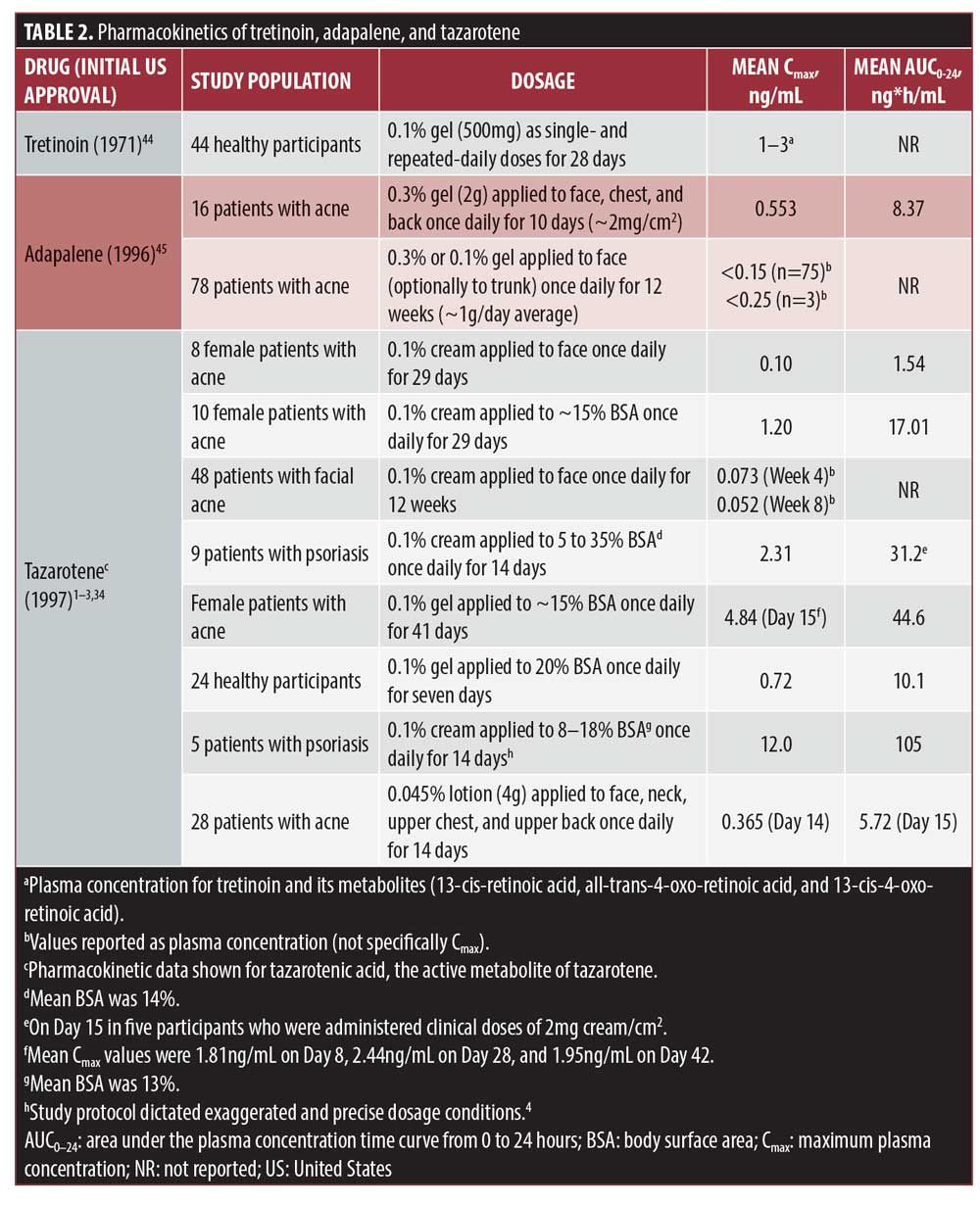

Under previous FDA pregnancy-labeling rules, topical tretinoin and adapalene were considered Category C and topical tazarotene was considered Category X (Table 1), even though resulting plasma retinoid levels from treatment with each were all similarly low (Table 2).5,31 One reason for differences in labeling is that tazarotene received simultaneous FDA-approval for the treatment of acne and psoriasis using pharmacokinetic data from psoriasis studies rather than from acne studies.5 Psoriasis studies estimated pharmacokinetic data based on use of tazarotene on up to 20-percent body surface area, whereas the face accounts for only two percent of the entire body surface area.5 The revised FDA pregnancy and lactation labeling note that tazarotene gel is contraindicated in pregnancy, but it is also noted that exposure levels that could lead to teratogenicity in humans are unknown.1 In males of reproductive potential, no guidance is provided. Furthermore, the effects of topical tazarotene on fertility in human males are unknown; studies in animals, however, show no detrimental effects.2,3

Pharmacokinetics of Tazarotene

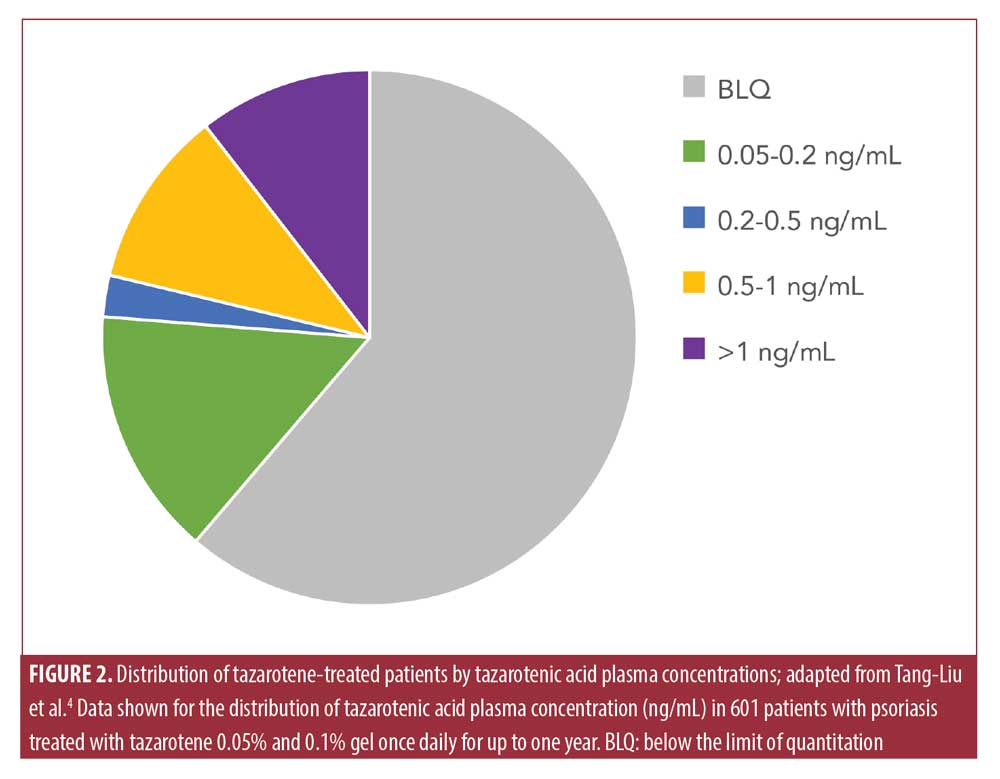

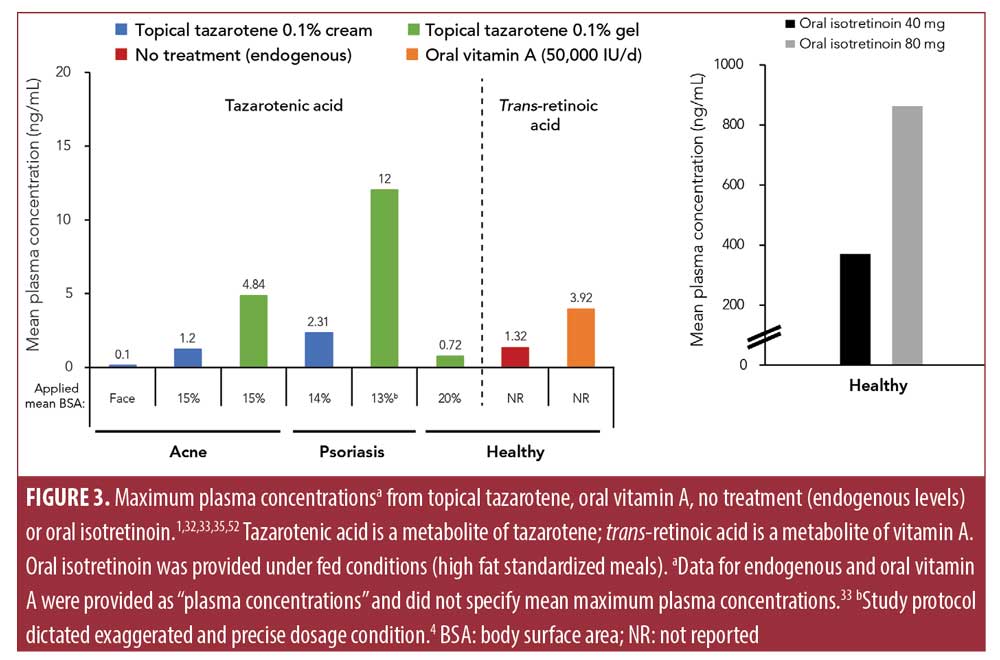

Low systemic exposure to a drug may reduce the potential risk of teratogenicity.5 Topical tazarotene has limited percutaneous penetration, rapid metabolism to hydrophilic metabolites (preventing accumulation in adipose tissue), and rapid elimination, all of which contribute to a low systemic exposure (Figure 2).4,32 Tazarotene has a mean half-life of 17 to 18 hours.4 Systemic bioavailability with 0.1% monotherapy dosing was 1% in healthy participants after single and multiple applications; in patients with psoriasis, bioavailability was one percent and there was an increase to five percent by Week 2, but this decreased by Week 12.4 This increase in bioavailability may have been due to a compromised epidermal barrier that occurs in patients with psoriasis; in addition, initial tazarotene treatment can thin psoriatic plaques and further reduce the skin barrier. After 12 weeks, skin barrier properties may have been reestablished, reducing permeability to tazarotene. In patients with acne and psoriasis treated with 0.1% tazarotene cream, tazarotenic acid plasma levels were similar to endogenous retinoid levels measured in healthy volunteers and lower than in healthy volunteers dosed with vitamin A (Figure 3).5,33,34 Single 40mg or 80mg doses of oral isotretinoin, by comparison, had similar or slightly longer half-lives of 18 or 21 hours than topical tazarotene but 30 to 70 times greater mean plasma concentrations, respectively (Figure 3). Overall, these data indicate that systemic exposure from topical tazarotene 0.1% is generally low and similar to endogenous retinoid levels.

While topical retinoids provide low systemic exposure and have demonstrated a positive safety profile in acne and psoriasis clinical trials, topical or oral retinoid use during pregnancy is not recommended. Retinoid-associated malformations and developmental delays have been observed in the offspring of rats and rabbits given oral retinoids during pregnancy.1,2,5,32 There have also been reports of retinoid-associated abnormalities in humans. The oral retinoid isotretinoin was approved for the treatment of severe recalcitrant nodular acne in the US in 1982; in the years since approval, there have been confirmed reports of major congenital malformations, some leading to death, in children who were exposed in utero.35,36 Women taking isotretinoin are also at increased risk for spontaneous abortions and premature births. For tazarotene, oral and topical formulations have shown teratogenic effects in pregnant rats and rabbits treated with doses greater than the maximum recommended human dose,1 but as noted previously, the level of exposure that could lead to teratogenicity in humans is unknown.1,5

Pregnancy Outcomes with Tazarotene

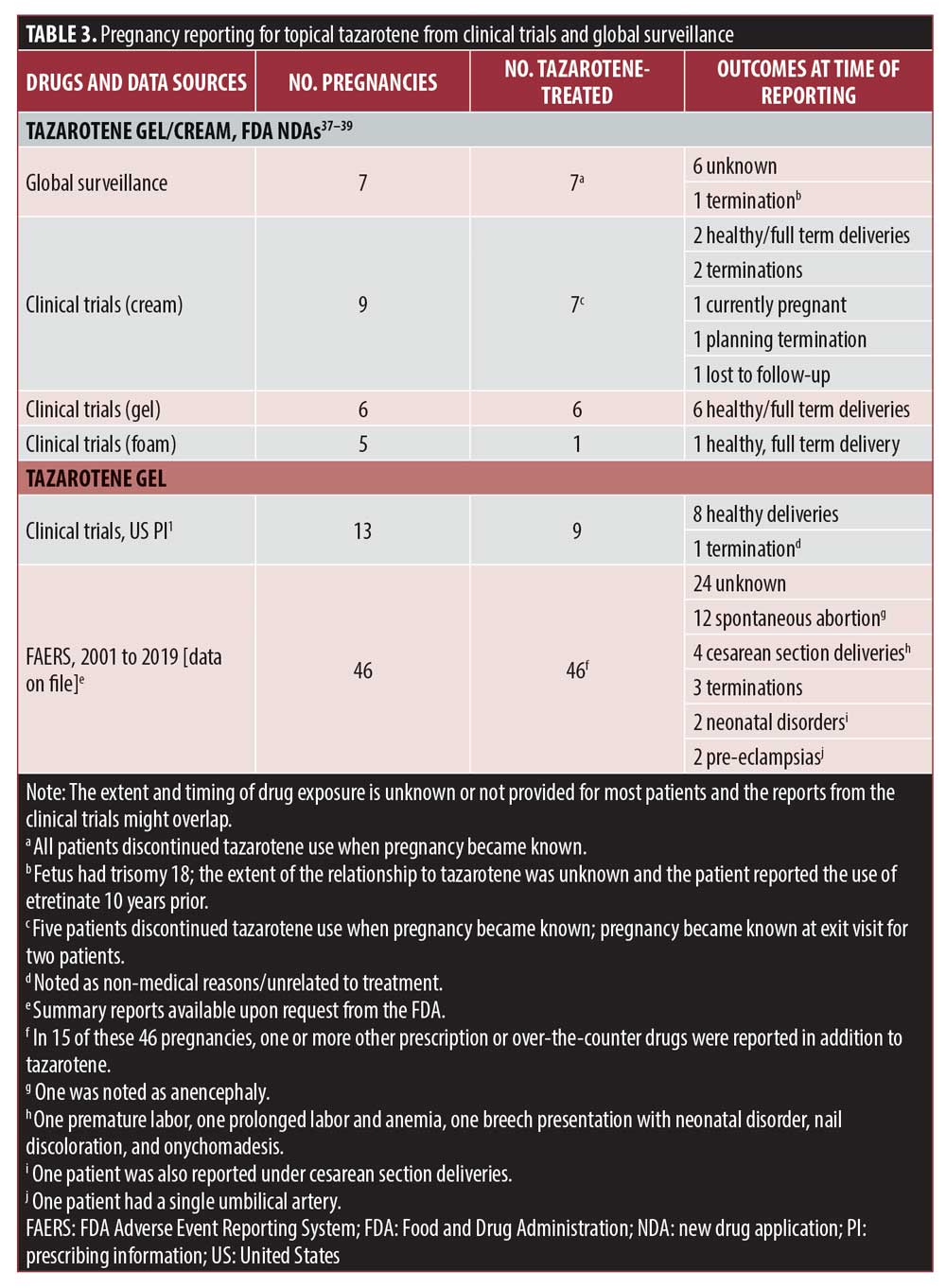

Data from FDA New Drug Applications, global surveillance, and FDA reporting indicate that there have been 76 reports of pregnancies in clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance of topical tazarotene, though it is unknown if any of these reports overlap and represent the same pregnancies (Table 3).1,37–39 Unfortunately, limited details regarding the outcomes were reported. Further, the extent and timing of drug exposure was unknown or not provided for most patients. Of the 76 pregnancies, the most common outcomes reported were unknown/lost to follow-up (n=31), healthy or caesarian delivery (n=21), spontaneous abortion (n=12), and termination/planned termination of pregnancy (n=8). Given the lack of information on timing and extent of exposure to tazarotene during pregnancy—as well as exposure to any other medicines during that time—the significance of the outcomes is unknown.1,5

Pregnancy Outcomes with Retinoid Exposure

Limited pregnancy outcomes data have been published on topical tazarotene specifically, with most articles focusing on tretinoin or other retinoids. A large retrospective analysis using data from US healthcare claims databases from 2011–2015 examined 86,834 isotretinoin-exposed, 973,587 tretinoin-exposed, and 5,302,105 unexposed matched pregnancies.40 Risk of spontaneous abortions was similar across groups and rates of pregnancy terminations were higher in isotretinoin-exposed pregnancies (28%) than tretinoin-exposed (10%) or unexposed pregnancies (6%). Malformations occurred at similar rates between the tretinoin-exposed (4.5%) and unexposed pregnancies (4.2%); malformation rates in the isotretinoin group were too low to assess.

A meta-analysis of outcomes in pregnancies with first trimester retinoid exposure employed a search of multiple databases up to the year 2014.41 The meta-analysis included 590 infants born to 654 pregnant women who were exposed to a topical retinoid during pregnancy, as well as 1,278 infants born to 1,375 unexposed women (control group). No significant differences between the exposed versus unexposed groups were found for major congenital malformations (odds ratio [95% confidence interval]: 1.22 [0.65–2.29]), spontaneous abortions (1.02 [0.64–1.63]), stillbirths (2.06 [0.43–9.86]), elective terminations (1.89 [0.52–6.80]), low birthweight (1.01 [0.31–3.27])or prematurity (0.69 [0.39–1.23]).

Case Studies of In Utero Retinoid Exposure

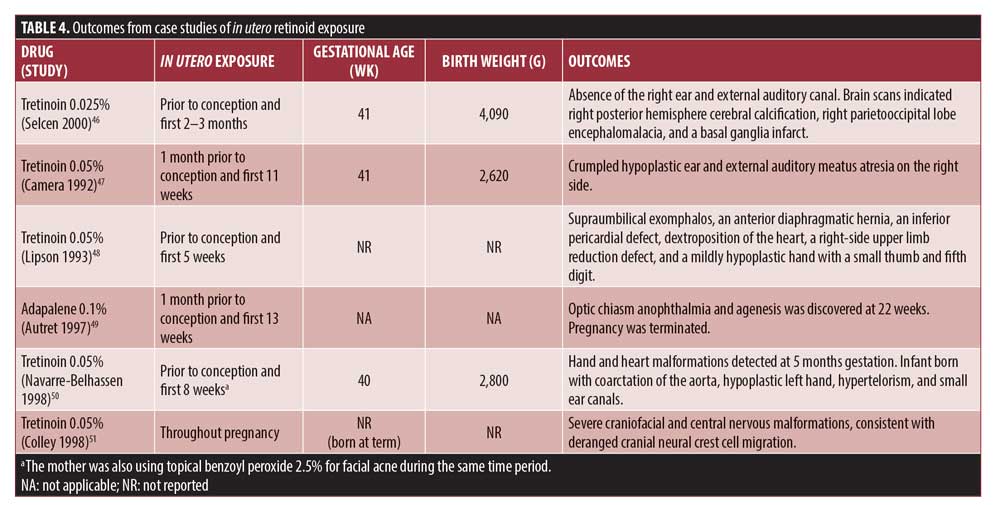

Presented in Table 4 are outcomes from six case studies of in utero topical tretinoin or adapalene exposure. All exposure occurred prior to conception as well as during the first trimester. There were three live births and one termination. It is unclear to what extent, if any, retinoid exposure affected fetal development in these cases.

Conclusion

As acne is a very common disease in women of child-bearing age and topical retinoids are a typical treatment, it is possible that some of these women will be exposed to a topical retinoid during pregnancy. Pharmacokinetic studies show relatively low systemic exposure from topical tazarotene, similar to that of endogenous retinoids. While there are case reports of topical tretinoin and adapalene exposure in utero, it is unclear if either affected fetal development. In terms of topical tazarotene, there is little published data on pregnancy outcomes in patients exposed to topical tazarotene. Additional case reports and outcomes studies are needed to further explore the safety of topical tazarotene in pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Lynn M. Anderson, PhD, and Jaqueline Benjamin, PhD, of Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, Ilinois) with financial support from Ortho Dermatologics. Ortho Dermatologics is a division of Bausch Health US, LLC.

References

- Tazorac® (tazarotene) gel 0.05% and 0.1%. US prescribing information. Madison, NJ: Allergan USA, Inc.; 2018.

- Tazorac® (tazarotene) cream 0.05% and 0.1%. US prescribing information. Irvine, CA: Allergan; 2017.

- Arazlo™ (tazarotene) lotion 0.045%. US prescribing information. Bridgewater, NJ: Bausch Health US, LLC; 2019.

- Tang-Liu DD, Matsumoto RM, Usansky JI. Clinical pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism of tazarotene: a novel topical treatment for acne and psoriasis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37(4):273–287.

- Menter A. Pharmacokinetics and safety of tazarotene. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2 Pt 3):S31–35.

- Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, et al. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976-2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):51 e51–58.

- Tinker SC, Broussard CS, Frey MT, Gilboa SM. Prevalence of prescription medication use among non-pregnant women of childbearing age and pregnant women in the United States: NHANES, 1999-2006. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(5):1097–1106.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologic Evaluation and Research. Reviewer Guidance: Evaluating the Risks of Drug Exposure in Human Pregnancies. 2005 [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/evaluating-risks-drug-exposure-human-pregnancies]. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Scialli AR, Buelke-Sam JL, Chambers CD, et al. Communicating risks during pregnancy: a workshop on the use of data from animal developmental toxicity studies in pregnancy labels for drugs. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70(1):7–12.

- Parisi MA, Spong CY, Zajicek A, Guttmacher AE. We don’t know what we don’t study: the case for research on medication effects in pregnancy. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157C(3):247–250.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products; Requirements for Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling. Federal Register. 2008;73(104):30831.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products; Requirements for Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Final Rule and Notice. Federal Register. 2014;79(233).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologic Evaluation and Research. Pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential: Labeling for human prescription drug and biological products — content and format guidance for industry. Draft guidance. 2014 [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/pregnancy-lactation-and-reproductive-potential-labeling-human-prescription-drug-and-biological]. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Lim L, Thompson K. New prescription drug labeling for pregnant or nursing women. Pharmacy Today. 2016;22(5):40–41.

- Adam MP, Polifka JE, Friedman JM. Evolving knowledge of the teratogenicity of medications in human pregnancy. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157c(3):175–182.

- van Gelder MM, de Jong-van den Berg LT, Roeleveld N. Drugs associated with teratogenic mechanisms. Part II: a literature review of the evidence on human risks. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(1):168–183.

- Weigle N, McBane S. Psoriasis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(9):626–633.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945–973.e933.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377–385.

- Hoffman LK, Bhatia N, Zeichner J, Kircik LH. Topical vehicle formulations in the treatment of acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(6):s6–s10.

- Latter G, Grice JE, Mohammed Y, Roberts MS, Benson HAE. Targeted topical delivery of retinoids in the management of acne vulgaris: Current formulations and novel delivery systems. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(10).

- Center Watch. Drug information: FDA approved drugs for dermatology. 2019 [Available from: https://www.centerwatch.com/directories/1067-fda-approved-drugs/topic/94-dermatology]. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- Weinstein GD, Krueger GG, Lowe NJ, et al. Tazarotene gel, a new retinoid, for topical therapy of psoriasis: vehicle-controlled study of safety, efficacy, and duration of therapeutic effect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(1):85–92.

- Krueger GG, Drake LA, Elias PM, et al. The safety and efficacy of tazarotene gel, a topical acetylenic retinoid, in the treatment of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(1): 57–60.

- Gold Stein L, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: Results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(2):287–293.

- Shalita AR, Chalker DK, Griffith RF, et al. Tazarotene gel is safe and effective in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a multicenter, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. Cutis. 1999;63(6):349–354.

- Feldman SR, Werner CP, Alio Saenz AB. The efficacy and tolerability of tazarotene foam, 0.1%, in the treatment of acne vulgaris in 2 multicenter, randomized, vehicle-controlled, double-blind studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(4):438–446.

- Shalita AR, Berson DS, Thiboutot DM, et al. Effects of tazarotene 0.1 % cream in the treatment of facial acne vulgaris: pooled results from two multicenter, double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group trials. Clin Ther. 2004;26(11):1865–1873.

- Tanghetti EA, Kircik LH, Green LJ, et al. A phase 2, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical study to compare the safety and efficacy of a novel tazarotene 0.045% lotion and tazarotene 0.1% cream in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(6):542–548.

- Tanghetti EA, Werschler WP, Lain T, Guenin E. Tazarotene 0.045% lotion for once-daily treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris: Results from two phase 3 trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(1).

- Chien AL, Qi J, Rainer B, Sachs DL, Helfrich YR. Treatment of acne in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(2): 254–262.

- Marks R. Pharmacokinetics and safety review of tazarotene. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(4 Pt 2):S134–138.

- Eckhoff C, Nau H. Identification and quantitation of all-trans- and 13-cis-retinoic acid and 13-cis-4-oxoretinoic acid in human plasma. J Lipid Res. 1990;31(8):1445–1454.

- Tazorac® (tazarotene) cream. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research approval package for: application number 21–184 . Clinical pharmacology/biopharmaceutics review. [Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2000/21-184_Tazorac.cfm].

- Absorica® (isotretinoin capsules). US prescribing information. Cranbury, NJ: Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.; 2019.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1(3):162–169.

- Tazorac® (tazarotene) cream. Center for Drug Evaluation and Reserach approval package for: application number 21-184 . Medical review, part 3. [Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2000/21-184_Tazorac.cfm].

- Tazorac® (tazarotene) gel. Center for Drug Evaluation and Reserach approval package for: application number 20-0600 . Medical review, part 5. [Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/97/020600_tazorac_toc.cfm].

- Fabior® (tazarotene) foam. Center for Drug Evaluation and Reserach approval package for: application number 202428 . Medical review, part 5. [Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2012/202428Orig1s000MedR.pdf].

- MacDonald SC, Cohen JM, Panchaud A, et al. Identifying pregnancies in insurance claims data: Methods and application to retinoid teratogenic surveillance. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(9):1211–1221.

- Kaplan YC, Ozsarfati J, Etwel F, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following first-trimester exposure to topical retinoids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(5):1132–1141.

- Thorpe PG, Gilboa SM, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Medications in the first trimester of pregnancy: most common exposures and critical gaps in understanding fetal risk. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(9):1013–1018.

- Andrade SE, Raebel MA, Morse AN, et al. Use of prescription medications with a potential for fetal harm among pregnant women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(8):546–554.

- Retin-A Micro® (tretinoin) gel microsphere 0.1%, 0.08%, 0.06%, and 0.04%. US prescribing information. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC: 2017.

- Differin® (adapalene) gel 0.3%. US prescribing information. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2012.

- Selcen D, Seidman S, Nigro MA. Otocerebral anomalies associated with topical tretinoin use. Brain Dev. 2000;22(4):218–220.

- Camera G, Pregliasco P. Ear malformation in baby born to mother using tretinoin cream. Lancet (London, England). 1992;339(8794):687.

- Lipson AH, Collins F, Webster WS. Multiple congenital defects associated with maternal use of topical tretinoin. Lancet (London, England). 1993;341(8856):1352–1353.

- Autret E, Berjot M, Jonville-Bera AP, Aubry MC, Moraine C. Anophthalmia and agenesis of optic chiasma associated with adapalene gel in early pregnancy. Lancet (London, England). 1997;350(9074):339.

- Navarre-Belhassen C, Blanchet P, Hillaire-Buys D, Sarda P, Blayac JP. Multiple congenital malformations associated with topical tretinoin. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32(4): 505–506.

- Colley SM, Walpole I, Fabian VA, Kakulas BA. Topical tretinoin and fetal malformations. Med J Aust. 1998;168(9):467.

- Accutane® (isotretinoin capsules). US prescribing information.Roche Laboratories, Inc., Nutley, NJ; 2008.