J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2025;18(7–8 Suppl 1):30–40.

by Abby Gaskell, DMSc, MSPAS, PA-C; and Kirsten Brondstater, DMSc, MSPAS, PA-C

Drs. Gaskell and Brondstater are with Shenandoah University in Winchester, Virginia.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: This manuscript was written as part of the requirements for Shenandoah University Doctor of Medical Science Program. Dr. Gaskell is a trainer for PDO Max and Prollenium. The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article, no financial affiliations or disclosures.

Abstract: The growing demand for aesthetic procedures leads to an influx of providers entering the field, many of whom lack formal training in aesthetic medicine. The absence of standardized education and certification poses significant risks to patient safety, including improper technique, adverse complications, and unethical practice. Without clear regulatory oversight, nonmedically trained individuals and inadequately trained healthcare professionals offer aesthetic treatments, leading to inconsistent outcomes and diminished public trust in the field. This article examines the urgent need for regulated training and certification to establish competency benchmarks and ensure patient safety. A tiered education model provides foundational, intermediate, and expert-level training, with standardized curricula covering anatomy, injection techniques, complication management, ethics, and legal considerations. Professional organizations and regulatory bodies play a key role in accrediting training programs, defining the scope of practice, and enforcing licensure requirements. Legislative measures, including mandatory certification, continuing education, and enforcement mechanisms, maintain high standards in aesthetic medicine. Implementing a structured training framework enhances provider competency, reduces adverse events, and reinforces ethical practice. Standardized regulation safeguards patient well-being and preserves the credibility and integrity of the aesthetic medicine industry.

Keywords: Aesthetic medicine, patient safety, regulated training, certification, competency standards, medical ethics, scope of practice

Introduction

Aesthetic medicine is experiencing exponential growth, with more healthcare providers entering into the field due to increasing demand for minimally invasive cosmetic procedures (MICP).1 Medical aesthetics includes nonsurgical cosmetic treatments for the face and body such as injectables (eg, botulinum toxin, dermal fillers, biostimulators), energy-based therapies, chemical peels, and body sculpting.2 Nonsurgical aesthetic (NSA) procedures can be performed by physicians, general practitioners, and nonphysician technicians.3 Whom can perform NSA procedures varies in the United States (US). Despite this growth, there is an absence of standardized and regulated training, which poses significant risks including inconsistent patient outcomes, safety concerns, and practitioner competency disparities. Many providers undergo brief training programs or weekend courses before performing complex aesthetic procedures, leading to potential complications and ethical concerns. Given the rapid growth of the field of aesthetic medicine, there is a need for regulated training and certification for providers. The objective of this article is to review the gaps in aesthetic medicine training, evaluate the consequences of unregulated education, propose an aesthetic curriculum, and advocate for policy changes to establish a standardized framework that enhances patient safety and provider competency.

Medical aesthetics: Consumer-driven medicine, an industry on the rise

The shifting perspectives of consumers on wellness, beauty, and healthy aging is leading to greater awareness and acceptance of aesthetic treatments, establishing them as essential aspects of regular self-care. The rising demand for NSA procedures stems from several factors: a cultural emphasis on youth and self-image, economic prosperity in particular, among executives and retiring baby boomers, advancements in technology and cosmeceuticals, media-driven hype, aggressive advertising, weakening institutional and cultural constraints, and a lack of regulatory oversight distinguishing evidence-based practices from unproven procedures.4 This fuels consumer-driven medicine, where industry profit heavily influences medical practices.4

A comprehensive survey conducted in 2021 by McKinsey & Company suggests the annual revenue of aesthetic medicine is projected to grow by 12 percent over the next five years, and the industry is estimated to grow by up to 14 percent annually through 2026.1 According to The Aesthetic Society’s 2023 annual statistics, a total of 4,594,458 soft tissue filler and neuromodulator procedures were performed in the US in 2022, including 649,176 filler treatments and 3,945,282 toxin procedures. This reflects year-over-year increases of 13 percent and 24 percent respectively.5 These rising numbers emphasize the growing acceptance and prevalence of minimally invasive treatments performed by both physician and nonphysician aesthetic practitioners.6,7 The aesthetic industry continues to experience steady growth with the total number of medical spas increasing from 8,899 in 2022 to 10,488 in 2023.8 As aesthetic treatments provide patients with innovative solutions and offer business owners financial opportunities, the growth of medical spas in the US continues to grow.

The current state of training in aesthetic medicine

Despite the growing demand for NSA procedures, the educational path for aesthetic practitioners lacks a structured curriculum, standardized certification, or monitoring by national or international boards or governing bodies.4,7,9 The lack of standardized education leaves aesthetic medical training to private institutions, individual educators, and pharmaceutical companies, resulting in numerous options but no quality control.9 Currently, no national or international standards exist for aesthetic medicine education or competency milestones. This unregulated system raises concerns about patient safety, as private sector training might offer limited benefit. This variability in training leads to significant disparities in providers skill levels and an unregulated aesthetic arena of education, which can lead to suboptimal patient outcomes.9 A problem with the aesthetic industry is there is a lack of consensus about what adequate training is and looks like.10

Who can inject? Regulations on neurotoxin and dermal filler administration varies across the US. Typically, licensed medical professionals including physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), physician assistants (PAs), registered nurses (RNs), and in some cases, dentists, estheticians, and dental hygienists are authorized to perform these procedures, often with specific supervision and training. To administer NSA treatments, providers must hold a healthcare license and complete a brief training course, often lasting a day or weekend. However, eligibility and requirements differ by state (Table 1).8,11–15

It is important to consider regardless of professional designation, individuals must complete appropriate training in administering injectables to ensure patient safety and compliance with state regulations. The level of required supervision varies by state and professional roles. Some states mandate direct on site supervision by a physician, while others allow for collaborative agreements or off site supervision.3 Professionals performing NSA must operate within the scope of practice as defined by their state’s licensing board. This dictates the procedures they are authorized to perform. Given the complexity and variability of state laws, it is crucial for practitioners to consult their state’s medical or nursing board for the most up-to-date current regulations. Additionally, seeking legal counsel experienced in healthcare law provides guidance tailored to specific circumstances and ensures compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.

Even where regulations exist, enforcement is often inconsistent and poorly defined. State level laws governing aesthetic medicine vary widely, leading to confusion about scope of practice, delegation, and supervision. In some states, oversight is minimal or outdated, allowing unqualified individuals to perform high-risk procedures with little accountability. Compounding the issue is the difficulty in finding legal counsel with specific expertise in aesthetic medicine, leaving many providers unaware of their legal responsibilities or vulnerable to unintentional violations. A standardized, enforceable regulatory framework is needed to protect patients and guide providers across all states.

Risks associated with inadequate training

The lack of regulation and standardized training in aesthetic medicine presents significant challenges to patient safety, provider competency, ethical and legal considerations, and the credibility of aesthetics as a medical specialty. Currently there is very little mandatory control of the aesthetic practice. However, there is no industry consensus about what adequate training looks like.10 Patients are only fully protected through legislation that mandates practitioners to meet specific standards before practicing.

Complications and patient safety issues. Adequate training is essential for patient safety, as complications often stem from insufficient anatomical knowledge and hands-on experience.3 The lack of formal education allows underqualified practitioners to perform complex procedures, increasing risks of complications, dissatisfaction, and ethical concerns.2 The rise of medical spas amplifies safety concerns, with common complications including burns, scarring, infections, and vascular compromise.16

Complications associated with individuals not properly trained in aesthetic injectables varies and can be severe. According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the most common complications associated with neurotoxin injections include pain, swelling, bruising, eyelid ptosis, eyebrow ptosis, watery or dry eyes, and a crooked smile.17,18 Serious neurotoxin complications include dysphagia, botulism, and possibly death.17 The most common filler complications reported to the FDA includes swelling, bruising, lumps, nodules, infection, tissue discoloration, and pain. Serious reported complications include tissue necrosis, vison loss, cerebrovascular accidents (CVA), granulomas, and anaphylaxis.19–24 Inexperienced injectors are at a higher risk of causing intra-arterial injections, which can lead to necrosis, and possible blindness. CVA and ophthalmic artery occlusion are rare but catastrophic complications that can occur when fillers are injected by inexperienced practitioners.23,25 Delayed immunologic reactions leading to severe immune responses can occur due to the use of unapproved materials by unlicensed practitioners.26

Patient safety issues occur due to lack of adequate training. This includes incorrect injection techniques such as inadvertently injecting into blood vessels, or poor injection technique resulting in asymmetry or drooping. Failure to recognize or manage complications can result in serious complications such as tissue necrosis or visual changes.20,25 Some untrained providers might purchase counterfeit products or overdilute products resulting in increased risk of infection or reduced efficacy. A lack of aseptic technique can introduce bacterial infections, leading to abscesses, granulomas, or systemic infections.26 Inappropriate patient selection and poor medical screening can result in patients being at a higher risk for complications. Mismanagement of injectable complications can result in delayed or incorrect treatment, lack of emergency preparedness, and failure to provide informed consent or post-treatment care. Standardized training and certification are crucial to ensuring providers can prevent and manage these risks and complications effectively.

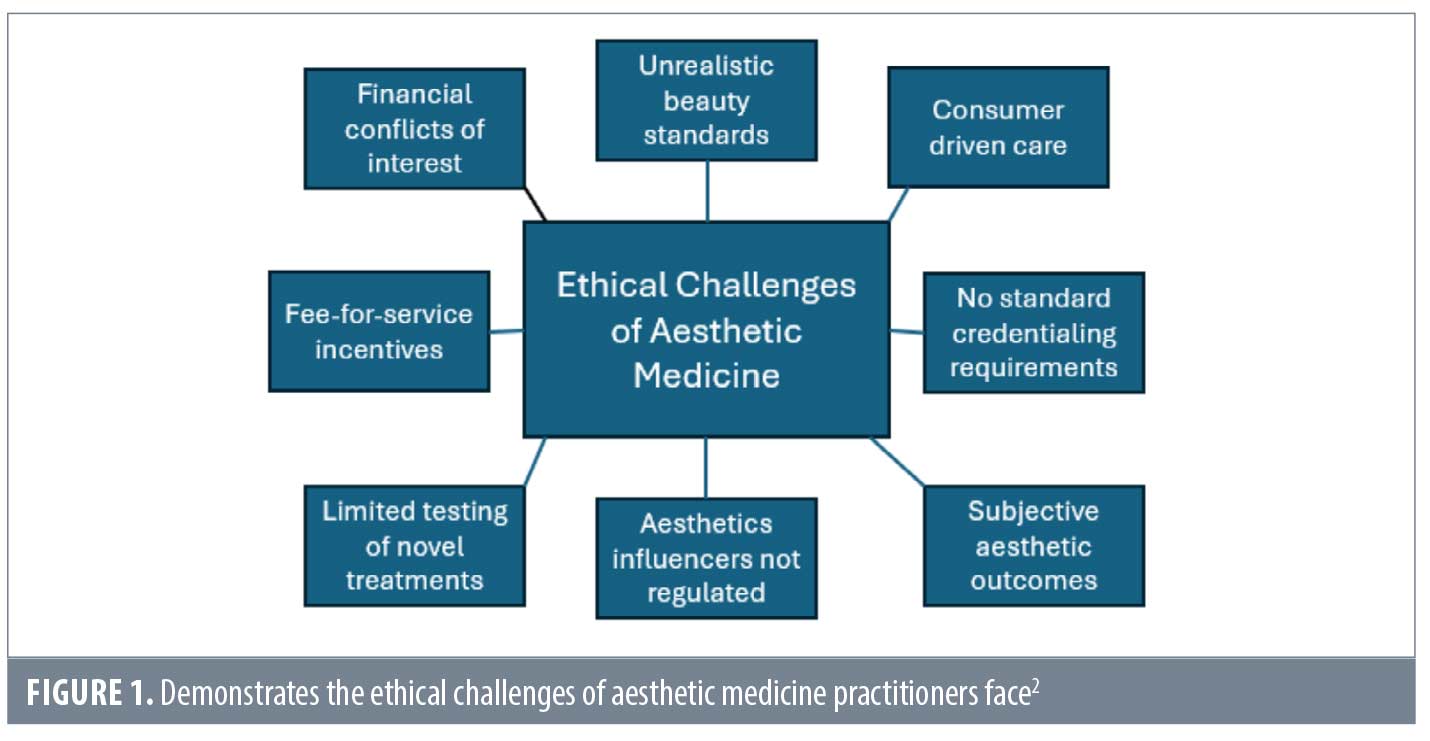

Ethical and legal considerations. Standardized education for providers entering into aesthetics is essential for ethical and legal reasons. Unlike traditional fields of medicine that focus on treating illnesses and saving lives, aesthetics is elective, and often influences by external factors and societal pressures shifts to a consumer-led approach.2,4 The ethical challenges of aesthetic medicine are multifaceted, with one of the primary challenges being the difficulty to measure outcomes (Figure 1).2 While traditional areas of medicine often present a clear outcome, measuring and defining beauty is elusive.27

Without standardized training, patients are unknowingly treated by underqualified practitioners, which presents a lack of informed consent, transparency, and misrepresentation of credentials.2 Some providers market themselves as “experts” in injectables without formal training or medical background. The rising demand for aesthetic procedures has led to a surge in unqualified providers offering unproven treatments and making unsupported claims. Many medical and dental practitioners now perform aesthetic procedures without formal training, leaving the public unable to distinguish qualified professionals from untrained providers.4 As a result, public trust in the medical profession is declining, as some practitioners promote non-evidence-based treatments, align with beauticians, and use media to commercialize and trivialize medical services.2,4

Failure to disclose risk is another ethical concern among untrained aesthetic providers. Ethical practice requires full disclosure of potential complications, side effects, and limitations of aesthetic procedures.2 Inadequately trained practitioners might downplay risks to secure business leading to misleading or unethical advertising. Patients have the right to autonomy and to make informed decisions about their care. This is undermined when they are not fully aware of the qualification of their providers or potential risks of procedures.4 Downplaying risks to secure business shifts aesthetic medicine from patient-centered care to profit-driven, thus prioritizing revenue and unethical business practices over patient wellbeing. Overtreating patients, upselling unnecessary procedures, or using cheaper products compromises ethical integrity.2,4

Lack of formal training, onsite supervision of medical directors, and a lack of experience provides ethical and legal concerns. Many medical spas operate without adhering to state guidelines regarding medical directorship, practitioner supervision, bypass regulations, or operate without proper licensing or malpractice insurance.3 A survey finds that nearly 30 percent of medical spa directors never perform NSA procedures, with some physicians paid to serve as directors without daily involvement.28 A study in Florida finds that a significant proportion of med spas lack proper licensing and do not comply with state regulations, highlighting the need for stricter oversight and regulation.29 According to the American Med Spa Association (AmSpa), 69 percent of medical spa directors are non-core, meaning a medical specialty other than dermatology, plastic surgery, otorhinolaryngology, or ophthalmology.15,30 Additionally, the top-reported specialty backgrounds of medical directors are family medicine and obstetrics/gynecology.3 Adequate training is essential for medical directors providing oversight in preventing complications and for patient safety.

Insufficient supervision and lax enforcement of scope-of-practice guidelines pose significant risks to patient safety and professional accountability, particularly in cases where non-core specialists, such as chiropractors or dentists, act as medical directors without adequate training in aesthetic medicine. In many states, vague or permissive language allows these individuals to oversee procedures they are neither trained to perform nor fully qualified to supervise, creating dangerous gaps in oversight. Regardless of their background, medical directiors must be held to rigorous training standards specific to aesthetic medicine, including anatomy and physiology, pharmacology, hands-on procedural education complication management, and legal responsibilities. Additionally, proximity requirements, should be considered; medical directors should be located within a reasonable geographic distance from the practice they oversee to allow for timely consultation, emergency support, and effective oversight. To prevent diluted supervision, limitations should also be placed on the number of providers any one director oversees. Finally, regulatory bodies should examine and restrict financial conflicts of interest, such as incentives tied to product-specific usage, which might compromise clinical integrity. Establishing clear qualifications, proximity expectations, and ethical safeguards for medical directors is essential to advancing safety and professionalism in aesthetic medicine.

Maintaining the integrity and credibility of aesthetic medicine. Standardized education is essential for provider competency and the credibility of aesthetic medicine. Regulatory oversight and credentialing prevent unqualified practice and ensure consistent care. The absence of clear training guidelines results in inconsistent patient outcomes, damaging trust in the field. A structured curriculum in anatomy, injection techniques, and patient assessment equips providers with necessary skills. The American Board of Plastic Surgery (ABPS) enforces rigorous certification, underscoring the need for universal standards.31 Uniform education and board certification establishes aesthetic medicine as a recognized specialty, enhancing legitimacy and public trust. Patients rely on “board-certified” credentials to choose qualified providers, reinforcing the need for stringent training requirements.31

Evaluating the impact of formal training in aesthetics

Current literature underscores the critical need for regulation in aesthetic medicine training, and reveals that inconsistent education standards contribute to increased patient risks, with compilations often arising from inadequate knowledge of facial anatomy, improper injection techniques, and a lack of crisis management skills.10

Several studies demonstrate the necessity of embedding NSA into medical education to improve patient safety and standardize provider competencies. One study finds the growing demand for NSA and evaluates whether it should be included in formal education.32 The purpose of this study is to gain insight into the views of final-year medical students and assess their understanding of NSA competence and complications. Despite a large proportion of medical students considering a career in NSA, a majority were unaware of their associated complications. The authors highlight the ethical and practical implications of this gap, advocating for a structured, tiered training model in NSA to be included in formal medical education.32

A literature review examines current debates surrounding the integration of aesthetic medicine into dermatology residency, as current formal hands-on cosmetic training lacks structure.33 This review adopts a multidisciplinary perspective, incorporating viewpoints from educators and practitioners to propose a balanced approach to a curriculum design, as well as an argument and counterargument to different viewpoints, and presenting means to overcome barriers. The authors conclude that incorporating aesthetics into medical training is feasible and beneficial but requires careful planning to not overburden dermatology medical residents.33

Additional studies demonstrate that structured education programs and hands-on training improve patient outcomes, patient satisfaction, and practitioner competence. One study finds simulation-based training has shown to be effective and demonstrates trainees who underwent hands-on simulation training for botulinum toxin injections have significantly higher practical tests scores compared to those who receive video training only.34 Similarly, another study supports the idea that experiential education and performing a higher volume of procedures enhances preparedness and confidence in performing cosmetic procedures independently.35 Additionally, fellowship and mentorship programs improve the number and scope of aesthetic procedures performed thus enhancing provider confidence.36 Formal training in the aesthetic industry, whether through structured educational programs, simulation training, resident clinics, or fellowships, significantly improves practitioner competence and patient outcomes.

Proposed framework for regulated training and certification

The establishment of a formalized tiered education model in aesthetics emphasizes the role of professional organizations and regulatory bodies, and outlines policy recommendations to establish standardized, evidence-based training and certification for all aesthetic practitioners. Authors assert the need for specialized training in NSA and recommend the inclusion of evidence-based programs in educational curriculum.4,9,33,37

The current regulatory landscape in aesthetic medicine lacks uniformity and clarity, particularly in delineating the responsibilities, training requirements, and oversight across provider types. A tier-based regulatory framework is essential to ensure safe and competent care by aligning requirements with providers’ education, scope of practice, and procedural risk. This model must include not only physicians, but PAs, NPs, RNs, and non-core specialists who are increasingly entering the field of aesthetic medicine.

Tier-based regulation recognizes that providers bring varying levels of training and clinical readiness. While core specialists like plastic surgeons are trained to manage complex procedures, other aesthetic providers may lack foundational knowledge in anatomy and pharmacology in aesthetics, requiring more structured education and supervision. Without such a system, it is difficult for patients to gauge provider competency, increasing the risk of harm.

Defining levels of competency in aesthetic medicine. Identifying levels of competency in aesthetic medicine is essential for ensuring patient safety, standardizing training, and improving patient outcomes. Cotofana et al9 establishes an educational framework in aesthetic medicine and defines the progression of injector levels from novice to competent to expert level (Table 2). Establishing competency levels ensures that practitioners have the necessary knowledge and skills to minimize complications. This competency creates a structured learning path, helping practitioners progress from basic to advanced procedures in a way that builds expertise systematically. Defining competency levels can help guide regulatory bodies in setting appropriate licensure or certification requirements thus reducing the risk of unqualified individuals performing high-risk procedures and improving patient satisfaction and outcomes. A clear competency framework distinguishes between different levels of expertise thus fostering public trust in aesthetic medicine. It also ensures that roles and responsibilities are clearly defined to facilitate effective collaboration.

Establishment of a proposed tiered education model. A structured, tiered approach to training ensures that practitioners acquire the necessary skills and knowledge at each level before advancing. By combining a tiered education model with aesthetic competency, this ensures practitioners acquire the necessary hands-on skills, knowledge, and volume of procedures at each level prior to advancing.

Tier 1 is foundational/basic level training or a novice injector. This training is open to licensed medical professionals (MDs, DOs, NPs, PAs, RNs, and dentists where permitted by law) depending on state laws. Tier 1 will focus on core principles of aesthetic medicine including: anatomy and physiology, fundamentals of neurotoxin and dermal fillers, the science of aging, the art of facial assessment and consultation, injection techniques, aseptic protocols, and recognition and management of common complications. Completion of Tier 1 requires a log of completion of the number of novice procedures as well as written and practical assessments.

Tier 2 is intermediate training or a competent injector, is open to professionals who have completed Tier 1, and acquired a minimum number of supervised procedures. Tier 2 expands on education covering advanced anatomy and high-risk areas, injection techniques (cannula, full-face rejuvenation), complication management (vascular occlusion, delayed hypersensitivity reactions), and the use of adjunctive treatments (lasers, skin booster, plasma rich proteins [PRP], microneedling, chemical peels). In this tier, practitioners complete a hands-on training with mentorship under experience injectors. A written exam along with practical assessment, and completed documented number of competency procedures is required for advancement to Tier 3.

Tier 3 is expert-level training or an expert injector. This tier is for highly experienced practitioners seeking specializations. This training covers advanced aesthetic procedures (combination treatments, ultrasound guided injections), ethical considerations, patient selection strategies, teaching, and mentorship roles in aesthetic medicines. Tier 3 requires completion of minimum case logs and procedures, participation in research, and/or teaching. A certification exam is required for completion and is granted by professional boards.

Proposed core curriculum for nonsurgical facial aesthetics (NSFA): A proposed core curriculum for NSFA encompasses a comprehensive and structured educational framework to ensure practitioners are prepared, and feel confident for independent practice (Tables 3–8 demonstrate the proposed curriculum topics).37,38 According to authors, a postgraduate program in NSFA ideally lasts 12 months long and utilizes a work-based learning approach. The curriculum includes key components such as foundational knowledge, practical skills, ethical and legal considerations, professional identity formation, interdisciplinary collaboration, continuous assessment, and feedback. Consensus on inclusion criteria for a core syllabus including anatomical aesthetic zones, NSFA basic science and clinical science, professionalism, regulation, compliance, research methods, and critical thinking is established using a Delphi survey of consensus of experts worldwide.37,38 The proposed curricula serve as a blueprint for structuring evidence-based courses in NSFA.

To ensure the proposed core curriculum for NSFA remains relevant and comprehensive, it expands beyond facial procedures to encompass the broader scope of services commonly offered in aesthetic practices today. This includes body contouring treatments such injectable lipolysis, cellulite reduction, and skin tightening procedures. Training also covers the safe and effective use of energy-based devices (EBDS), including radiofrequency, laser, IPL, and high-intensity focused ultrasound technologies. Incorporating ultrasound into the curriculum, as both a diagnostic and procedural safety tool, supports improved complication prevention and vascular mapping. Additionally, as many aesthetic practices integrate wellness services, the curriculum introduces foundation knowledge in adjunct subfields such as intravenous (IV) therapy, medical weight loss, bioidentical hormone replacement therapy (BHRT), and peptide therapies. As aesthetic medicine evolves into a more holistic model of health optimization and rejuvenation, educational programs must reflect this interdisciplinary shift by preparing providers to deliver safe, ethical, and evidence-based care across the full spectrum of offerings.

Roles of professional organizations and regulatory bodies. Professional organizations and regulatory bodies are essential to establish standardization and evidence-based training for aesthetic providers (Table 9). Societies provide networking opportunities and professional development, advocate for higher standards of patient safety, ethical practice, and evidence-based treatments, organize annual conferences, workshops, and research initiatives, and promote collaboration between medical professionals, researchers and industry leaders.39 Professional organizations establish standardized curricula, competency benchmarks, and certification guidelines. Organizations provide accreditation for training programs, mentorship initiatives, offer continuing medical education (CME) courses to ensure practitioners remain up to date, and facilitate peer review research and dissemination to advance aesthetic medicine.40 Regulatory bodies define scope of practice for different medical professionals in aesthetics, implement licensing and credentialing requirements for injectors, develop and enforce patient safety regulations, monitor and penalize unlicensed or unsafe practitioners, and collaborate with profession organizations to maintain high standards of care.41

The development of an aesthetic certification involves the collaboration between societies, professional organizations, and regulatory bodies to ensure high standards of practice and public safety. Professional organizations, such as the American Board of Plastic Surgery (ABPS) and the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery (ABCS), play a role in defining the certification requirements, including the necessary training, examinations, and continuing education.42 Regulatory bodies are responsible for licensing physicians and ensuring they meet the minimum competency standards to practice medicine. These bodies can work with professional organizations to recognize and enforce certification standards, ensuring that only qualified practitioners can advertise themselves as “board certified” in aesthetic procedures.31,43

Establishment of a standardized certification process within each country to regulate and credential aesthetic practitioners requires completion of an accredited training program, mandates a practical assessment and written exam, enforces recertification and continuing education requirements, and is overseen by national regulatory agencies and professional boards.43 International certification requires development of an internationally recognized credential to ensure uniformity in aesthetic medicine training and practice. This involves collaboration among global professional organizations, establishment of universal competency standards, implementation of international accreditation bodies to certify training institutions, and encourages global mobility and standardization in aesthetic medicine.44,45 Overall, the certification process is designed to hold high standards of medical care and ensure that practitioners are competent and knowledgeable in their fields.

Certifying bodies in aesthetic medicine and the inclusion of PAs. Certification through the ABPS and the Certified Aesthetic Nurse Specialists (CANS) program represents two of the most recognized pathways for validating provider competency in aesthetic medicine. The ABPS, a member board of the American Board of Medical Specialties, certifies plastic surgeons who have completed rigorous surgical training and passed comprehensive examinations.42 This credential serves as a gold standard in aesthetic surgery, reflecting both procedural expertise and adherence to safety protocols. Similarly, the CANS certification, administered by the Plastic Surgical Nursing Certification Board in collaboration with the American Society of Plastic Surgical Nurses, offers a benchmark for registered nurses in aesthetics, validating their experience, ethical standards, and knowledge of core principles.46 Both certifications help reinforce public trust and support professional accountability in an otherwise unregulated field. However, access to these credentials is currently limited by provider type and specialty, underscoring the need for broader, inclusive certification models that reflect the evolving, multidisciplinary nature of aesthetic medicine.

There is a growing need to expand such credentialing pathways to include PAs, who comprise a significant and increasing portion of the aesthetic workforce. Advocacy for a universal, crossdisciplinary standard is essential. This standard requires completion of a comprehensive training curriculum that includes cadaver dissection for anatomical competence, a minimum number of supervised hands-on procedures and procedure hours, and a foundational understanding of regulatory and legal responsibilities. Organizations like The Society for Aesthetic PAs (SAPA) emerge to fill this gap by promoting education, networking, and professionalism among aesthetic PAs.47 Supporting their efforts and integrating their input into national certification frameworks helps ensure PAs are held to the same safety and competency benchmarks as their physician and nursing counterparts. Broadening certification opportunities and standardizing education across disciplines improves patient outcomes but also enhances the credibility and cohesion of the aesthetic medicine field.

Recommendations for policy implementation. Policy implementation in aesthetic medicine must prioritize patient safety, ethical practice, and high standards of care. This begins with legislative and licensing requirements, including mandated minimum training hours, certification exams before administering injectables, and restricting aesthetic procedures to licensed medical professionals. A state and national database should track certified providers. Standardized training and certification are essential. Accredited programs must ensure consistent education, periodic recertification, and continuing education. Mentorship and residency-style training should provide hands-on experience. Enforcement and oversight are critical. Regular aesthetic clinic inspections must ensure compliance, with penalties for unauthorized practice and unethical marketing. Public awareness campaigns should help patients identify qualified providers.

Diversity and equity training in aesthetic medicine. As aesthetic medicine embraces a more diverse patient base, it must also evolve to ensure culturally competent and clinically appropriate care. Diversity and equity in training for NSFA remain significant challenges, with current curricula often lacking structured, standardized education that addresses the needs of diverse patient populations. The lack of standardized training disproportionately affects the ability of clinicians to deliver safe and effective care to patients from varied racial and ethnic backgrounds, as well as to understand the unique anatomical, cultural, and aesthetic considerations relevant to these groups.48

The medical literature highlights that people of color and individuals from different ethnic backgrounds increasingly seek NSFA procedures, yet persistent gaps in clinician education exist regarding the assessment, procedural selection, and complication management specific to these populations. This includes understanding differences in skin structure and anatomical variations based on ethnicity, such as facial architecture, skin thickness, and vascular patterns, as well as recognizing how aesthetic conditions, treatment responses, and risks (eg, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloid formation, vascular occlusion, burns) present differently in skin of color. Culturally informed aesthetic ideals must also be considered when developing treatment plans, selecting products, and performing procedures. Addressing these gaps requires explicit incorporation of diversity-focused content and hands-on experience with patients of different backgrounds into training programs.48–54

Diversity and equity training is a critical yet often overlooked component of aesthetic education. As the patient population seeking cosmetic treatments becomes increasingly diverse, providers must be equipped with knowledge and skills to deliver culturally competent and clinically appropriate care. Beyond clinical competence, training should incorporate cultural sensitivity, addressing patient expectations, beauty norms, and communication styles across various backgrounds. Integrating these elements into core curricula and certification promotes health equity, enhances patient trust, and reduces disparities in aesthetic outcomes. A standardized approach to diversity education ensures that all providers, regardless of background, are prepared to offer safe, respectful, and personalized care to any and all patients. As the patient population grows more diverse, providers must recognize anatomical variations, understand skin-specific risks, and respectfully navigate cultural expectations. Incorporating this training into aesthetic education not only improves outcomes and patient satisfaction but also upholds the ethical responsibility of equitable care across all communities.

Conclusion: What the future of aesthetic medicine looks like, a call to action

The rapid expansion of aesthetic medicine exposes critical gaps in training, regulation, and patient safety. The absence of standardized education and credentialing leads to inconsistent practice standards, an increase in complications, and public confusion regarding provider qualifications. A structured, tiered training framework ranging from foundational education to expert-level certification ensures that practitioners develop the necessary skills and competencies before performing aesthetic procedures. Professional organizations, regulatory bodies, and societies play a crucial role in establishing clear guidelines, enforcing licensing requirements, and promoting evidence-based practices in aesthetic medicine.

To address these challenges, mandatory certification and regulated training programs must be implemented at both national and international levels. Governments and medical boards, and nursing boards must collaborate to adopt policies that require formal education, practical assessments, and continuing education to maintain competency across all provider types. Medical boards play a central role in regulatory oversight, ensuring that licensed providers meet defined standards of care, adhere to scope of practice boundaries, and fulfill continuing education requirements. The inclusion of nursing boards is especially critical given the large number of nurses entering aesthetic medicine and the direct involvement of patient care. Regulatory cohesion across professions helps ensure consistency and safety regardless of provider title. Additionally, the development of global accreditation standards enhances the credibility of aesthetic medicine and protects patients from unqualified or poorly trained practitioners. These standards recognize the contributions of all healthcare disciplines and set consistent expectations for training, ethics, and scope of practice.

Future research focuses on evaluating patient outcomes based on provider training levels, the effectiveness of certification programs, and the long-term impact of regulatory changes on safety and ethical standards. Collaboration among professional organizations, policymakers, and educators is essential to refine best practices and ensure that aesthetic medicine evolves as a well-regulated, patient-centered field. Standardizing training and certification is not just an industry necessity, but a fundamental step toward protecting patient safety, improving clinical outcomes, and maintaining public trust in the field of aesthetic medicine.

References

- Here to stay: An attractive future for medical aesthetics. McKinsey & Company. February 1, 2024. Accessed April 12, 2025. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/life-sciences/our-insights/here-to-stay-an-attractive-future-for-medical-aesthetics.

- Ramirez S, Cullen C, Ahdoot R, Scherz G. The primacy of ethics in aesthetic medicine: a review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12(6):e5935.

- Valiga A, Albornoz C, Chitsazzadeh V, et al. Medical spa facilities and nonphysician operators in aesthetics. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:239–243.

- Goh C. The need for evidence-based aesthetic dermatology practice. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009;2(2):65–71.

- The Aesthetic Society. Aesthetic plastic surgery national databank statistics 2022. Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43(Suppl 2):1–19.

- Khetpal S, Lopez J, Steinbacher D. The rise of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in medically necessary, noninvasive aesthetic procedures for Medicare beneficiaries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(1):163e–165e.

- Jones JK, Bennett S, Erlandsson M, et al. Aesthetic medicine nurses and qualified nonmedical practitioners: our role and requirements as aesthetic medicine adapts to worldwide changes and needs. Plast Surg Nurs. 2018;38(4):153–157.

- Meyer M. 2024 medical spa state of the industry executive report recap. November 6, 2024. Accessed April 12, 2025. https://americanmedspa.org/blog/2024-medical-spa-state-of-the-industry-executive-report-recap.

- Cotofana S, Mehta T, Davidovic K, et al. Identify levels of competency in aesthetic medicine: a questionnaire-based study. Aesthet Surg J. 2024;44(10):1105–1117.

- Pearce T. The importance of safety and training in medical aesthetics. May 2, 2019. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.aestheticnursing.co.uk/content/professional/the-importance-of-safety-and-training-in-medical-aesthetics.

- Moeller M. What are the rules for who can inject neurotoxins? American Med Spa Association. June 29, 2021. Acessed July 15, 2025. https://americanmedspa.org/blog/what-are-the-rules-for-who-can-inject-neurotoxins.

- What states allow estheticians to do injections? FACE Med Store. 2025. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://facemedstore.com/blogs/blog/what-states-allow-estheticians-to-do-injections.

- Botox Laws by State 2025. World Population Review. 2025. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/botox-laws-by-state.

- State by state dental botox regulations (USA). Dentox. 2025. Accessed July 15, 2025 https://dentox.com/state-by-state-dental-botox-regulations/.

- American Med Spa Association. Medical Spa State of the Industry: Executive Summary. 2022. Accessed April 12, 2025. https://americanmedspa.org/resources/med-spa-statistics.

- Wang JV, Albornoz C, Goldbach H, et al. Experiences with medical spas and associated complications: a survey of aesthetic practitioners. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(12):1543–1548.

- Ahsanuddin S, Roy S, Nasser W, et al. Adverse events associated with botox as reported in a food and drug administration database. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2021;45:1201–1209.

- Lee KC, Pascal AB, Halepas S, Koch A. What are the most commonly reported complications with cosmetic botulinum toxin type A treatments? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78(7):e1–e9.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dermal fillers (soft tissue fillers). FDA. July 6, 2023. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/aesthetic-cosmetic-devices/dermal-fillers-soft-tissue-fillers.

- Carruthers J, Fagien S, Rohrich RJ, et al. Blindness caused by cosmetic filler injection: a review of cause and therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(6):1197–1201.

- Doerfler L, Hanke C. Arterial occlusion and necrosis following hyaluronic acid injection and a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(6):587–591.

- Ortiz AE, Ahluwalia J, Song SS. Analysis of U.S. Food and Drug Administration data on soft-tissue filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(7):958–961.

- Beauvais D, Ferneini EM. Complications and litigation associated with injectable facial fillers: a cross-sectional study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78(1):133–140.

- Zhao F, Chen Y, He D, et al. Disastrous cerebral and ocular vascular complications after cosmetic facial filler injections: a retrospective case series study. Sci Rep. 2024;14:3495.

- Tripathi NV, Hakimi AA, Parsa KM, et al. Complications, treatment, and outcomes of self-injecting substances into the face: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2024;50(1):59–61.

- Seok J, Hong J, Park K, et al. Delayed immunologic complications due to injectable fillers by unlicensed practitioners: our experiences and a review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29(1).

- Liew S, Silberberg M, Chantrey J. Understanding and treating different patient archetypes in aesthetic medicine. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:296–302.

- Gibson J, Greif C, Nijhawan R. Evaluating public perceptions of cosmetic procedures in the medical spa and physician’s office settings: a large-scale survey. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49(7):693–696.

- Soares DJ, Bowhay A, Fakhre F, et al. The shifting face of aesthetic care: a systematic survey of independent medical spa directorship and practitioner trends in Florida. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;155(1):66e–74e.

- Hogan S, Wood E, Mishra V. Who is holding the syringe? A survey of truth in advertising among medical spas. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49(11):1001–1005.

- Hanemann MS, Wall HC, Dean JA. Preserving the legitimacy of board certification. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(6S):325–327.

- Rehman U, Freer F, Sarwar M, et al. Non-surgical facial aesthetics: should this be incorporated into medical education? Adv Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;8:100327.

- Kream EJ, Jones BA, Tsoukas MM. Balancing medical education in aesthetics: review and debate. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:283–291.

- Mitkov MV, Thomas CS, Cochuyt JJ, et al. Simulation: an effective method of teaching cosmetic botulinum toxin injection technique. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38(12):NP207–NP212.

- Weissler JM, Carney MJ, Yan C, et al. The value of a resident aesthetic clinic: a 7-year institutional review and survey of the chief resident experience. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(10):1188–1198.

- Montemurro P, Diehm YF, Hedén P, et al. Aesthetic surgery fellowship at Akademikliniken Stockholm: survey among graduates. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2025;49(9):2451–2458.

- Kumar N, Parsa A, Raham E. A core curriculum for postgraduate program in nonsurgical aesthetics: a cross-sectional Delphi study. Aesthet Surg J Open Forum. 2022:4:ojac023.

- Kumar N, Swift A, Rahman E. Development of “core syllabus” for facial anatomy teaching to aesthetic physicians: a Delphi consensus.Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(3):e1687.

- Vellios EE, Shybut T, Delman C. How to get involved with professional societies, locally, regionally, and at the national level. Clin Sports Med. 2025;44(1).

- Perlis C, Shannon N. Role of professional organizations in setting and enforcing ethical norms. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30(2):156–159.

- Benton D, Thomas K, Damgaard G, et al. State of nursing regulation: annual report 2017. J Nurs Regul. 2017;8(3):4–11.

- Chen S, Lineaweaver WC. Evaluating board certification within the aesthetic marketplace. Ann Plast Surg. 2024;93:S119–S122.

- Why become board certified. American Board of Medical Specialties. 2025. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.abms.org/board-certification/getting-board-certified/.

- Karle H. Global standards and accreditation in medical education: a view from the WFME. Acad Med. 2006;81(12 Suppl):S43–S48.

- Karle H. World Federation for Medical Education policy on international recognition of medical schools’ programme. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2008;37(12):1041–1043.

- Get Certified: CANS. Plastic Surgical Nursing Certification Board. 2025. https://psncb.org/CANS/.

- SAPA: The Society for Aesthetic PAs. American Med Spa Association. 2025. https://americanmedspa.org/aestheticpas.

- Quiñonez RL, Agbai ON, Burgess CM, Taylor SC. An update on cosmetic procedures in people of color. Part 1: Scientific background, assessment, preprocedure preparation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(4):715–725.

- Burgess C, Awosika O. Ethnic and gender considerations in the use of facial injectables: African-American patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5 Suppl):28S–31S.

- Quiñonez RL, Agbai ON, Burgess CM, Taylor SC. An update on cosmetic procedures in people of color. Part 2: Neuromodulators, soft tissue augmentation, chemexfoliating agents, and laser hair reduction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(4):729–739.

- Alexis AF, Few J, Callender VD, et al. Myths and knowledge gaps in the aesthetic treatment of patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(7):616–622.

- Gold M, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Algorithm for pre-/post-procedure measures in racial/ethnic populations treated with facial lasers, nonenergy devices, or injectables. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21(10):SF3509903–SF35099011.

- Nelson K, Nelson J, Bradley T, Burgess C. Cosmetic enhancement updates and pitfalls in patients of color. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41(3):547–555.

- Alexis A, Boyd C, Callender V, et al. Understanding the female African American facial aesthetic patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(9):858–866.