J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(3):18–26

by Mark S. Nestor, MD, PhD

by Mark S. Nestor, MD, PhD

Dr. Nestor is with the Center for Clinical and Cosmetic Research in Aventura, Florida as well as the Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery and Department of Surgery, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Miami, Florida.

FUNDING: Funding for this study was provided by a research grant from Sinclair Pharma. Additionally, funding for medical writing support was provided to Principal Medvantage, LLC by X-Medica, LLC via an educational grant from Sinclair Pharma.

DISCLOSURES: Dr. Nestor is a consultant and advisory board member for and has received research grants from Sinclair Pharma, the manufacturer of the study suture. He is also a consultant and advisory board member for Almirall.

ABSTRACT: Objective. We sought to provide short- and long-term data on the duration of results and patient satisfaction achievable with absorbable suspension sutures in the midface.

Design. This study included a prospective, masked, controlled 12-week study and 12-month extension study.

Setting. This study was conducted in a single center in Aventura, Florida.

Participants. Twenty female subjects 41 to 75 years of age with moderate facial skin laxity were included.

Measurements. Facial lift was measured using a three-dimensional surface imaging system. Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) scores were reported by subjects and investigators and FACE-Q questionnaires were collected from subjects at Weeks 1, 2, 8, and 12 and Month 12 after treatment.

Results. Statistically significant changes in lift were observed through Week 8 (30% of patients had ?1.5mm of lift [p=0.03]) and mean surface area of lift through Week 12 (patients with ?1.0mm facial lift had mean surface area of 4.4cm2 [p=0.156]). Improvements in subject and investigator GAIS were observed, along with statistically significant changes in FACE-Q assessments and patient-reported apparent age at each timepoint through 12 months. Subjects tolerated the procedure well, and adverse events were minimal.

Conclusion. Absorbable suspension sutures offer an adaptable, safe, minimally invasive approach to tissue lifting and repositioning. The suture provides immediate lift, followed by revolumization and ongoing recontouring that result from the collagen-stimulating properties of the suture, increasing long-term patient satisfaction.

KEYWORDS: Absorbable suspension sutures, absorbable suture, suspension suture, InstaLift, tissue repositioning, sutures, nonsurgical repositioning, recontouring, revolumization

Introduction

The hallmarks of facial aging include loss of facial volume, decreased skin quality, hyperkinetic movement, and descent of facial features. Inferior displacement of facial tissue is the result of both volume loss and ptosis from diminished skin elasticity,1 coupled with musculoskeletal changes that destabilize facial ligaments.2,3 Multiple options for treatment exist for some of the changes that can occur during aging, including devices for skin and facial tightening,4 as well as absorbable and nonabsorbable implantable sutures.5,6 Prior to the 2015 United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of absorbable advanced suspension technology for tissue repositioning, minimally invasive treatment options for tissue repositioning were limited. Absorbable suspension sutures are the first minimally invasive, entirely absorbable treatment option for tissue repositioning and recontouring that can be performed under local anesthesia and which demands very little patient downtime.5,7

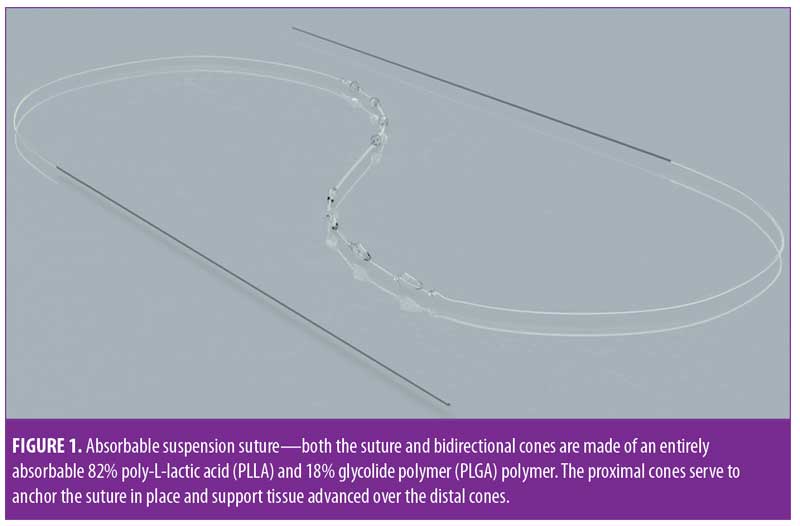

Absorbable suspension sutures (Silhouette InstaLift™; Sinclair Pharma, Irvine, California) are composed of 82% poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) and 18% glycolide polymer (PLGA). Each suture includes bidirectionally oriented cones made of the same material along the length of each suture (Figure 1). The bidirectional cones serve to anchor the superior side of the suture in more adherent or fibrous tissue so that tissue that is advanced over the inferior cones can be supported in an elevated position. Over time, the foreign body reaction and low-grade inflammatory response characteristics of PLLA lead to collagenases and revolumization8,9 along with an improvement in skin tone and texture.10 Sutures are available in three sizes (i.e., 8, 12, and 16 cones) to accommodate a range of facial shapes and sizes; however, in the experience of the author, as well as other expert users, the eight-cone suture is suitable for nearly all facial applications.7

While the immediate outcome of treatment with absorbable suspension sutures is lift and repositioning, the complementary collagen-stimulating activities of PLLA serve to provide volume and support longer-term revolumization and recontouring.7 To date, there exist neither published long-term study data documenting lifting and repositioning of the midface nor long-term patient satisfaction data regarding the use of absorbable suspension sutures. This research includes a prospective, masked, controlled 12-week study and a complementary 12-month extension study. Together, these studies provide both short- and long-term efficacy data on facial lift; data on patient satisfaction; and document the nature, duration, and type of improvement following treatment with absorbable suspension sutures. The results of the study can be used not only to inform clinical practice but also to support meaningful conversation with patients about treatment expectations and the nature and duration of treatment.

Methods

Study design. This prospective, masked, controlled investigation consisting of a 12-week study (N=20) and a 12-month extension study (N=11) measured facial lift and recontouring as well as subject satisfaction following treatment with absorbable suspension sutures on subjects 41 to 75 years old with moderate facial skin laxity (Table 1). Though the study was open to both male and female patients, only female patients were ultimately enrolled. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 2.

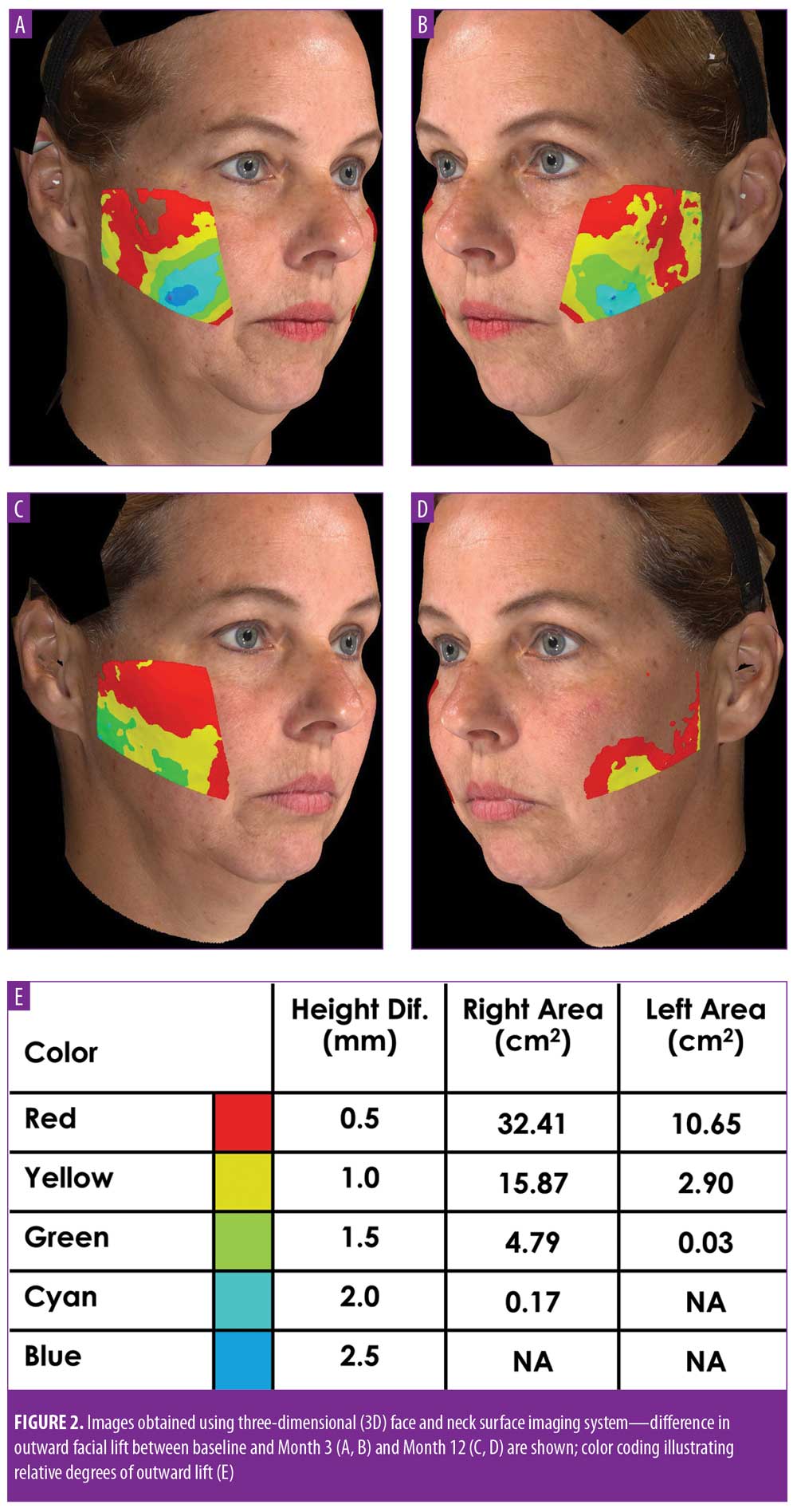

For both the 12-week and 12-month studies, the primary endpoint was efficacy as determined by the change in outward facial lift as calculated by comparing the projection of the skin’s surface in pretreatment images to that in post-treatment images using a three-dimensional (3D) surface imaging system (VECTRA M3 3D Imaging System, Canfield Scientific, Fairfield, New Jersey; Figure 2). A digital camera station was used to collect 3D images for use in measuring quantitative changes in lift and volume in the cheeks and two-dimensional images to document qualitative changes (Figure 2). Within the study, each subject served as their own control, with images collected at enrollment and at baseline 1 to 2 weeks later, just prior to the procedure, to account for variations inherent in the process of image collection. Following suture placement, follow-up visits were held at two days and one, two, eight, and 12 weeks postprocedure for the initial study and at 12 months postprocedure for the extension study. At each visit, two-dimensional and 3D images were collected. For determining lift and surface area with the 3D surface images, both sides of the face were measured and analyzed separately. McNemar’s test was used to evaluate facial lift, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed to evaluate differences in the total mean surface area of facial lift.

Secondary endpoints included patient satisfaction with cheek appearance and quality-of-life outcomes measured using the FACE-Q questionnaire, a validated and sensitive patient-reported outcomes instrument,11 and subject- and investigator-reported Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) scores.

Subject-reported outcomes were assessed using the following nine validated FACE-Q questionnaire areas:11 Satisfaction with Cheeks, Age Appraisal Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Satisfaction with Decision, Satisfaction with Outcome, Recovery—Early Symptoms, Recovery—Early Life Impact, Symptom Checklist, Psychological Wellbeing, and Social Function. Subjects completed the questionnaire at the time of enrollment and at one, two, eight, and 12 weeks and 12 months postprocedure.

Subject-reported outcomes also included GAIS scores, with data collected at one, two, eight, and 12 weeks and 12 months postprocedure. The treating investigator also independently completed the GAIS at one, two, eight, and 12 weeks and 12 months postprocedure. Both FACE-Q and GAIS data were collected for the left and right sides of the face combined. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate differences in FACE-Q outcomes.

All adverse events including serious adverse events, unanticipated problems, and unanticipated adverse device effects experienced as the result of treatment were recorded. Adverse events were reported through subject diaries (data collected at each follow-up visit) and at each postprocedure visit.

This study adhered to standards set by the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. Patient consent for the procedure and collection and publication of images included in this article was obtained.

Treatment. Consistent with expert clinical experiences, only eight-cone sutures were required in this study; specifically, exclusively eight-cone, absorbable suspension sutures made of PLLA and PLGA, as previously described, were used, and all sutures were placed as straight-line vectors.7,12 At least six sutures (3 on each side in the midface) were used in the midface of each subject. Of the 20 subjects, 10 received a total of eight sutures (4 on each side in the midface).

The procedures were performed consistent with consensus publication.7 With the patient in an upright position, the mobility of the tissue to be repositioned was evaluated, and the entry and exit points of the suture were identified and marked, using the ruler included in the device’s package. With the patient reclined at a 45-degree angle, the area was disinfected and local anesthesia (0.5cc of 1% or 2% lidocaine per site) was administered at the entry and exit points only, with a 30-gauge needle. The knots in the suture were tightened before placement by applying firm tension to the ends of the suture. The entry site was dilated with an 18-gauge needle inserted at a 90° angle to a depth of 5mm into the subcutaneous tissue. Sutures were then placed using the long, 23-gauge, 12-cm needle that comes with the absorbable suspension sutures. To place the sutures, the needle appended to the suture was inserted in a perpendicular fashion into the entry site until the 5-mm depth mark on the needle was reached. The needle was then turned to a 90-degree angle, taking care not to withdraw the needle before turning it, and advanced to and through the marked exit site, maintaining depth in the subcutaneous plane. The cones were then gently pulled through the entry site, closed side first. This procedure was repeated for the other arm of the suture. To confirm that there was no puckering, either due to cones catching on the dermis or through the inadvertent creation of a dermal bridge at the entry site, the suture was tensioned and the skin’s surface assessed for dimples or depressions.

Once all sutures were placed, the superior cones were engaged by gently massaging the overlying tissue, taking care not to advance the tissue, in order to seat the cones. Tissue to be repositioned was then advanced over the inferior cones up to the entry point. In some instances, as the tissue was engaged, visible gathering or pleating occurred, but dissipated within 2 to 3 days. After suture placement and tissue advancement, the patient was evaluated in the upright position. Following evaluation, any asymmetry or need for additional correction was managed. Once the results were deemed satisfactory, suture ends were trimmed and a finger was passed over the exit sites to ensure the trimmed suture end was below the surface of the skin. Antiseptic ointment was applied to all entry and exit points.

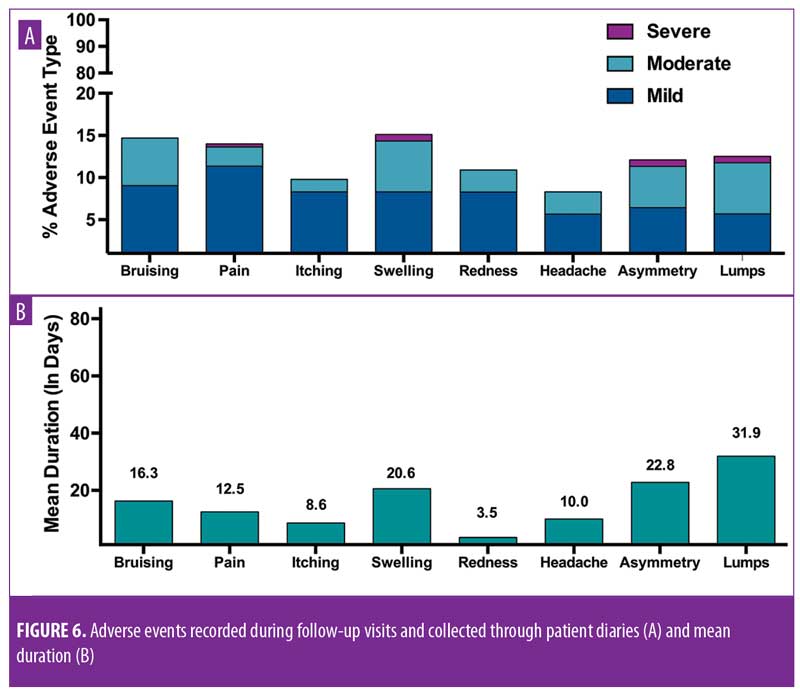

Specific instructions for strict postoperative care regimens were given to subjects. Specifically, patients were instructed to apply cold packs immediately after the procedure if required; use acetaminophen in the case of pain; apply make-up gently only after 24 hours; sleep face-up, elevated on pillows for 3 to 5 nights; wash, dry, and apply makeup to the face gently without rubbing for five days; eat soft foods and refrain from chewing gum for one week; avoid excessive facial movements and high-impact sports for two weeks; refrain from the use of saunas or steam rooms for three weeks; avoid dental surgery for three weeks; avoid direct sunlight/tanning beds for four weeks; and avoid facial or face-down massages and facial aesthetic treatments for four weeks. Adverse events were reported through subject diaries and at postprocedure visits. The adverse events verified by the investigator are shown in Figure 6. Only those adverse events reported through the 84-day, 12-week study period are shown, as there were no new adverse events reported after 84 days.

Results

Initial 12-week study. Statistically significant and meaningful changes in lifting were effectively measured by 3D surface imaging through Week 8 (Table 3 and Figures 2C and 2D). At Week 1, 100 percent of patients had facial lifts of 0.5mm or greater (p=0.002), 80 percent had 1.0mm or greater (p=0.0001), and 45 percent had 1.5mm or greater (p=0.004). At Week 8, 85 percent of patients had facial lifts of 0.5mm or greater (p=0.04), 50 percent had 1.0mm or greater (p=0.08), and 30 percent had 0.5mm (p=0.03) or greater. Mean surface area lifted was significant Weeks 1 to 12 (Table 4). For patients with 0.5mm or greater, 1.0mm or greater, or 1.5mm or greater facial lift, the total mean surface area of facial lift at one week post-treatment was 17cm2 (p?0.0001), 6.7cm2 (p?0.0001), and 2.8cm2 (p=0.002), respectively. At eight weeks post-treatment, the total mean surface area of facial lift was 11.5cm2 (p=0.0001), 1.0cm2 (p=0.004), and 0.5cm2 (p=0.03), respectively. At 12 weeks post-treatment, the total mean surface area of facial lift was 9.2cm2 (p=0.0013), 4.4cm2 (p=0.0156), and 0.5cm2 (p=0.0625; not significant), respectively.

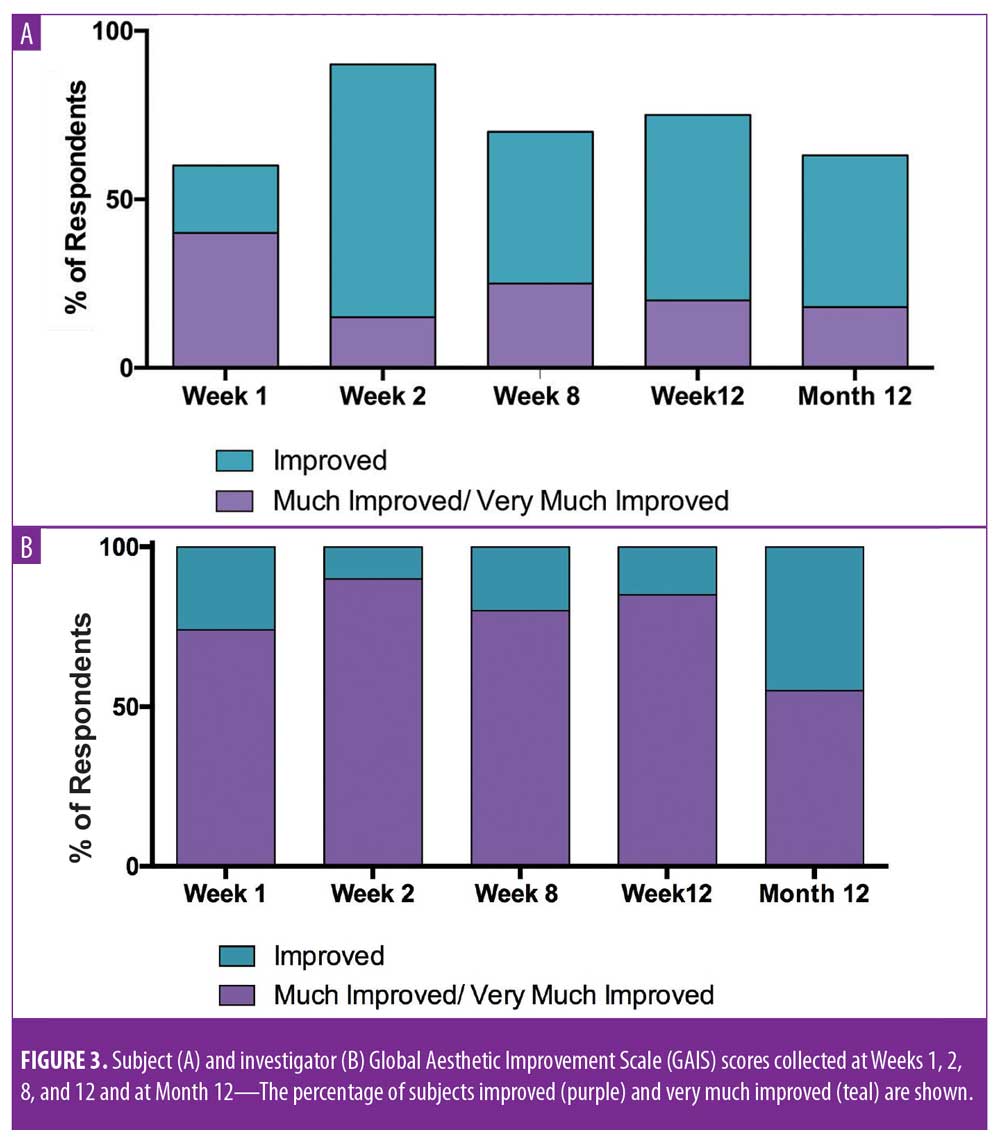

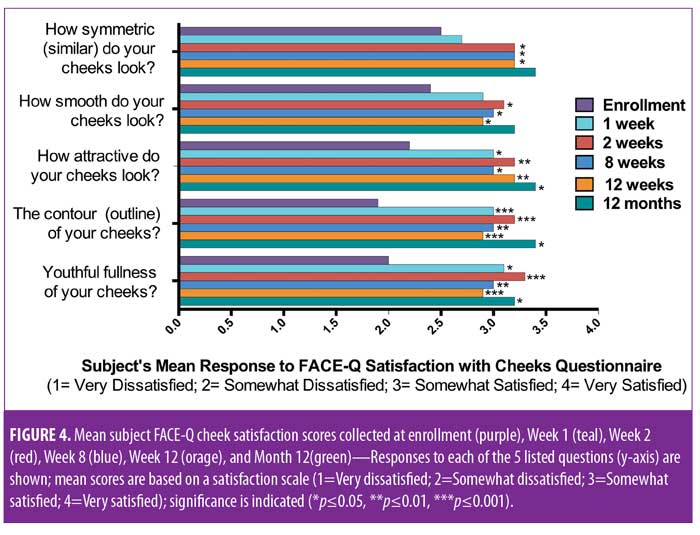

Meaningful changes in subject and investigator GAIS assessments were observed, with a majority of subjects reporting improvement at each time point (Figure 3). At one, two, eight, and 12 weeks post-treatment, 60, 90, 70, and 75 percent of subjects rated themselves as at least “improved” on the GAIS, respectively. Additionally, the investigator rated 100 percent of subjects at least “improved” on the GAIS at all timepoints. Statistically significant changes in FACE-Q satisfaction with cheeks score were observed at Weeks 1, 2, 8, and 12 (Figure 4).11 By Week 1, significant changes in satisfaction were noted for the contour of the cheeks (mean score of 3, change of 1.1 from baseline; p=0.0009) and the youthful fullness of the cheeks (mean score of 3.1, change of 1.2 from baseline; p=0.0018). Statistically significant improvements in satisfaction were noted for all survey questions (cheek symmetry, smoothness of cheeks, attractiveness of cheeks, contour of cheeks, and youthful fullness of cheeks) at Weeks 2, 8, and 12, with the exception of how smooth the cheeks looked (mean score of 3, change of 0.6 from baseline; p=0.0949) at Week 8.

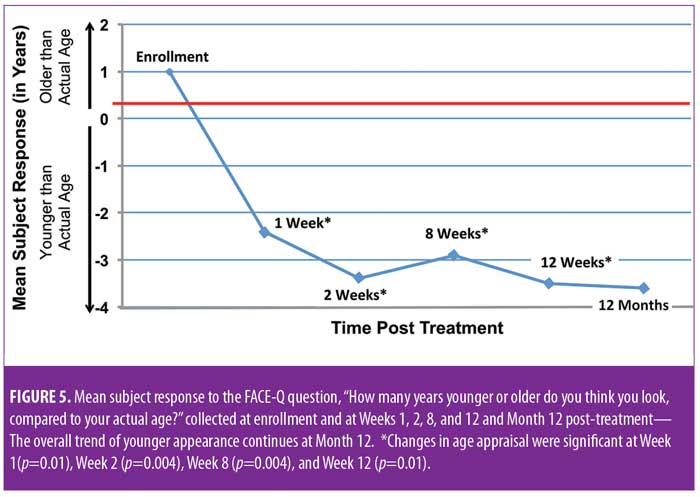

The combined impact of these measures on patient perception of apparent age was statistically significant. Changes in age appraisal were significant at one week (mean: -3.4, standard deviation [SD]: 5, range: -10–10; p=0.01), two weeks (mean: -4.6, SD: 5.7, range: -16–4; p=0.004), eight weeks (mean: -3.9, SD: 5.3, range: -14 –3; p=0.004), and 12 weeks (mean: -3.4, SD: 5.3, range: -14 – 6; p=0.01) (Figure 5). All reported adverse events were expected and were generally mild and of a short duration (Figures 6A and 6B). Of the 265 events reported in subject diaries, 11 were severe in nature (Figure 6A) and occurred in four subjects. Six of the 11 events occurred in a single subject, and most severe events occurred on the day of treatment and were resolved without sequelae. A single patient reported moderate tenderness that resolved after 10 weeks.

Twelve-month extension study. Results of the 12-month extension study demonstrate that, although individual subjects continued to show lift at 12 months, with 60 percent of patients having 0.5mm or greater, 50 percent having 1.0mm or greater, 20 percent having 1.5mm or greater, and 10 percent having 2.0mm or greater of facial lift (Figures 2C and 2D), the number of subjects followed for the 12-month extension was too small to show a statistically significant difference. The same was true for surface area change: although the total mean surface areas in patients with 0.5mm or greater, 1.0mm or greater, and 1.5mm or greater of facial lift were 6.4cm2, 2.1cm2, and 0.3cm2, respectively, the differences were not statistically significant (Tables 3 and 4). Subject and investigator GAIS scores (Figure 3), subject responses to FACE-Q cheek questions (Figure 4), and FACE-Q age appraisal question responses (Figure 5) concordantly reflect a continued benefit that is distinct from the lifting measured by the 3D face and neck surface imaging system. Through 12 months, improvements in subject satisfaction with cheek attractiveness (mean score of 3.36, change of 1.09 from baseline; p=0.0283), contour (mean score of 3.36, change of 1.18 from baseline; p=0.01), and youthful fullness (mean score of 3.18, change from baseline of 0.91; p=0.04) were statistically significant. This change can be qualitatively appreciated in subject photos (Figures 7 and 8) and is reflected by the overall trend of improvement in both satisfaction and clinical benefit. The overall trend of subject assessment of apparent age continued up to 12 months. Subjects often described the observed changes as “recontouring,” and additionally noted a remarkable change in skin quality. There were no new adverse events reported in the 12-month study, and none of the study participants had adverse events that were unresolved by the end of 12 weeks.

Discussion

Absorbable suspension sutures are the only available FDA-approved, nonsurgical modality for tissue repositioning, and the sutures themselves are entirely absorbable. As part of a holistic approach to rejuvenation, repositioning is a critically important addition to a treatment armamentarium that was previously restricted to hyperkinetic muscle relaxation, skin resurfacing, and tissue revolumization.5 Data from these prospective, masked, controlled 12-week and 12-month extension studies provide much-needed short- and long-term data on the nature and duration of the impact of absorbable suspension suture placement. The 12-week lift data support the use of sutures for tissue repositioning, and the 12-month data show the capacity of absorbable suspension sutures to support “recontouring” beyond the window of time in which they provide lift. Importantly, this feature is reflected in ongoing patient satisfaction and can be qualitatively appreciated in patient photos and patient-reported images changes in skin quality and facial contour. The duration of satisfaction at 12 months is consistent with the clinical experience of the author as well as other expert practitioners7 who observe that patients do not generally need to be retreated for 18 to 24 months. Importantly, there is no need for patients to return to baseline prior to retreatment. Rather, additional sutures can be placed at between 18 and 24 months to maintain and, in some cases, further improve results. While patients in this study were treated with 3 to 4 sutures in the midface, accumulating clinical experience since the time this study was initiated has revealed that optimal results are achieved with a holistic approach that most often includes four sutures in the midface, 1 to 2 sutures in the jowls or jawline, and two sutures in the upper neck, per side.7 Thus, to achieve optimal results in this setting, the treatment paradigm has evolved to most often include eight sutures per side. Even if treatment is restricted to the midface, an adequate number of sutures is critical for ensuring that there is sufficient support for repositioned tissue and that volumization induced by the suture’s PLLA/PGLA is optimal for achieving recontouring.

The original FDA 510K approval for absorbable lifting sutures required a permanent monofilament suture for fixation, despite the worldwide consensus that it was unnecessary and would increase the frequency of adverse events. In this study, the procedure, when performed without a permanent anchor suture, was well-tolerated, and the aesthetic results were maintained. These findings, coupled with the results of this study, led to an FDA-approved label change to the absorbable lifting suture product Instructions for Use (IFU) that eliminated the requirement for a permanent monofilament for fixation of the suspension suture to the fascia, harmonizing the IFU and common current clinical practice.

The recontouring described by subjects in the study reflects a larger pattern observed by the investigator in this study as well as by other experienced practitioners7—that is, the procedure appears to give rise to natural and satisfactory results in a broad range of patients. The procedure fills a gap in the rejuvenation treatment armamentarium, permitting tissue repositioning and lift with minimal downtime.5,7 Candidates for treatment with absorbable suspension sutures require repositioning of descended features, but might wish to delay or avoid surgery or maintain the results of a previously performed surgery. Like any procedure, clear communication with patients about the nature of the expected results is key to high satisfaction. While absorbable suspension sutures are not a substitute for a surgical facelift, they do provide a unique result of repositioning and lift with recontouring. Consistent with the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study, the ideal patient has string bony projections and skin that is mobile and pliable and of a sufficient thickness to avoid palpability of the sutures. Most often, the patient has some facial skin redundancy and a visible nasolabial fold and/or marionette lines. Patients with very thick or sundamaged skin might not be ideal candidates but might still benefit from treatment. In a recent consensus paper, several expert users explored in further depth the various noncannonical patients who benefit from treatment with absorbable suspension sutures.7

Absorbable suspension sutures can also be used in concert with other methodologies as part of a holistic approach to rejuvenation.5,7 For example, in patients who require lifting beyond what volume restoration with fillers can provide, complementary treatment with fillers and absorbable sutures can provide more complete revolumization. In addition, neurotoxins and absorbable suspension sutures can have a synergistic effect, in that the toxin relieves some of the force imposed by the musculature on the suture, allowing all of the force exerted by the suture to be applied towards lifting and repositioning tissue.

The reported changes in skin quality that are part of the recontouring effect of the sutures is likely linked to collagenases stimulated by the PLLA/PGLA sutures within the subcutaneous layer.10 One potential shortcoming of using the 3D imaging system to measure lift is that measures of change are restricted to changes in the projection of the skin’s surface. It might be that the effect of the sutures that gives rise to patient-reported positive changes in appearance are more closely linked with the repositioning or lateral movement of features rather than lift alone. In addition, absorbable suspension sutures are well-suited to be part of combination therapy with other modalities such as energy-based devices, resurfacing with lasers, neuromodulators, and fillers and are thus rarely used in isolation in clinical practice. The satisfaction recorded here is based on the activities of the sutures alone.

In order to more fully explore the elements of recontouring, studies with larger populations at 12- and 18-month follow-up intervals are warranted. In addition, studies exploring complementary or synergistic treatments can be used to more systematically explore ideal treatment approaches. Finally, the utility of sutures continues to expand, and off-label use in the jowls, jawline, and neck is emerging as part of a complete approach to tissue repositioning for rejuvenation.

The study shows that absorbable suspension sutures appear to offer a safe, minimally invasive approach for tissue lifting, repositioning, and recontouring. In addition to the suture’s lifting capacity, the PLLA within the suture has a biostimulatory effect, which contributes to the impact of the suture of facial recontouring. Often, patients for whom suspension sutures are an attractive treatment option present with a need for tissue repositioning and volumization beyond what fillers alone can provide. Absorbable suspension sutures are able to manage segmental facial laxity in a targeted and efficient way. The procedure takes approximately 20 minutes, has minimal downtime, and is associated with high patient satisfaction. The compatibility of absorbable suspension sutures with other treatment modalities, such as fillers, toxins, and energy-based devices, make them a valuable treatment option for facial rejuvenation.

Limitations. The results of this study are limited by small patient number. Longer term follow up is also warranted.

Conclusion

Data from this study support the use of absorbable suspension sutures as a means of achieving measurable facial lift through Week 8 postprocedure. Improvements in subject and investigator scales of cheek satisfaction and apparent age through 12 months were also observed. The absorbable suspension sutures appeared to provide immediate lift, followed by revolumization and an ongoing benefit described as “recontouring” up through the study duration of 12 months. Addiitonally, the procedure was well-tolerated, and the adverse events were minimal, suggesting that absorbable suspension sutures are an adaptable, safe, and minimally invasive approach to tissue lifting and repositioning.

Acknowledgments

The author thank Ginny Vachon, PhD, of Principal Medvantage, LLC for providing medical writing support.

References

- Wong CH, Mendelson B. Newer understanding of specific anatomic targets in the aging face as applied to injectables: aging changes in the craniofacial skeleton and facial ligaments. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5 Suppl):44S–48S.

- Kretlow JD, Hollier LH, Jr., Hatef DA. The facial aging debate of deflation versus attenuation: attenuation strikes back. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(1):180e–181e; author reply 182e.

- Cotofana S, Fratila AA, Schenck TL, et al. The anatomy of the aging face: a review. Facial Plast Surg. 2016;32(3):253–260.

- Chilukuri S, Lupton J. “Deep heating” noninvasive skin tightening devices: review of effectiveness and patient satisfaction. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(12):1262–1266.

- Nestor MS, Ablon G, Andriessen A, et al. Expert consensus on absorbable advanced suspension technology for facial tissue repositioning and volume enhancement. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(7):661–666.

- Paul MD. Barbed sutures in aesthetic plastic surgery: evolution of thought and process. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(3 Suppl):17S–31S.

- Lorenc ZP, Ablon G, Few J, et al. Expert consensus on achieving optimal outcomes with absorbable suspension suture technology for tissue repositioning and facial recontouring. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018; 17(6):647–655.

- Stein P, Vitavska O, Kind P, et al. The biological basis for poly-L-lactic acid-induced augmentation. J Dermatol Science. 2015;78(1):26–33.

- Goldberg D, Guana A, Volk A, et al. Single-arm study of the characterization of human tissue response to injectable poly-L-lactic acid. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(6):913–922.

- Goldberg, DJ. Non-barbed suture lifting and neocollagenesis: why does the skin look healthier? Oral presentation at: Vegas Cosmetic Surgery and Aesthetic Dermatology Annual Meeting; June 2018; Las Vegas, NV.

- Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Scott A, et al. Measuring patient-reported outcomes in facial aesthetic patients: development of the FACE-Q. Facial Plast Surg. 2010;26(4):303–309.

- Lorenc ZP, Goldberg DJ, Nestor MS. Straight-line vector planning for optimal results with Silhouette InstaLift in minimally invasive tissue repositioning for facial rejuvenation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(7):786–793.