J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17(7):20–22.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17(7):20–22.

by Jessica G. Irons, PhD; Noah D. Gustin; Rachel E. Zindler; and Morgan L. Ferretti, MA

All authors are with James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. Ms. Ferretti is also with the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Objective. Skin cancer remains prevalent despite numerous studies reporting the benefits of sunscreen for reducing risk of skin cancer and sunburn. While the risks of not wearing sunscreen are well-documented, there are no effective interventions to promote sunscreen use across populations, and existing interventions have modest outcomes. The current study investigated a novel intervention to increase sunscreen use.

Methods. Participants (n=15) first reported their baseline daily sunscreen use then completed sunscreen sampling and selection procedures that included testing sunscreen samples, choosing preferred sunscreens to take home and sample further, and ultimately selecting a preferred sunscreen to use for the remainder of the study. Participants then self-reported their daily sunscreen use for approximately two weeks (+/-5 days). Results. All participants increased sunscreen use following intervention.

Limitations. Data were collected between January and May; individuals may increase sunscreen use as temperatures increase (and time outdoors increases). Additionally, the current study relied on self-report of sunscreen use primarily.

Conclusion: Our findings suggest that sampling and election procedures may be an effective strategy to promote sunscreen use. The findings of this study may inform future research examining sunscreen intervention strategies.

Keywords. Sunscreen, intervention, skin cancer prevention, sun protection, sunscreen use

Introduction

Skin cancer (SC) is the most commonly occurring cancer in the United States (US) and worldwide; an estimated 6.1 million adults in the US are treated for basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas and 84,000 are treated for melanomas annually. Treatment for the roughly 6.1 million US adults that are treated for basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas costs approximately $8.9 billion. Projections suggest that in 2023, there will be 97,610 new cases of melanoma, the SC with highest mortality rate, in the US.2 Ultraviolet (UV) light exposure is the primary cause of cutaneous malignancies and the risk of developing SC is positively associated with sun exposure. Further, incidence of sunburn, also caused by sun exposure, predicts diagnosis of SC.3

The most effective sunburn and SC prevention strategy (other than avoiding sun exposure) is proper use of sunscreen, or protective clothing in conjunction with sunscreen use.4 Sunscreens have been shown to prevent sunburn, squamous cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and melanoma.3 Estimates suggest that a five-percent increase in the number of US residents using sunscreen per year would result in more than 230,000 fewer cases of melanoma across a ten-year span.5 Indeed, research has shown that rates of melanoma are about half among those who wear sunscreen consistently compared to those who do not.6 The data also shows that sunscreen use for SC prevention is more cost effective than treating SC.7

Despite data confirming benefits of consistent sunscreen use, rates of SC remain elevated among US residents.1 Consumer surveys suggest that up to 46 percent of surveyed US adults reported never wearing sunscreen.8 In addition to lack of use, research suggests that US adults might lack knowledge related to effective sunscreen use. Data shows that though most people surveyed knew that sunscreen can prevent sunburn and SC (86% and 70%, respectively), but only 32 percent knew to apply sunscreen 15 to 30 minutes before sun exposure and 10 percent knew how much sunscreen is necessary to achieve product-stated levels of protection.9 The data also shows low knowledge related to sunscreen and prevention of SC among healthcare providers, including doctors and pharmacists.10 Further, a study of dermatology patients (N=294) showed that fewer than 45 percent of patients received sunscreen-related counseling while visiting their dermatologist.11 Primary reasons that individuals do not use sunscreen include inconvenience, having no perceived need, and/or unpleasant side effects of use (e.g., breakouts, white cast, and shine).12

Education-based and prompt-based (i.e., reminders to wear sunscreen) interventions have demonstrated limited efficacy, even when administered by dermatologists among high-risk (e.g., individuals with skin cancer diagnoses) patient samples.13,14 Most studies evaluating interventions of this nature failed to report sufficient data to calculate effect sizes and/or observed power. Free sunscreen provision has been shown to increase sunscreen use and some approaches have combined sunscreen provision with other strategies.13 For example, at study by Nicol et al15 recruited 364 beach goers and divided them into three groups. The first group received four free sunscreen options with traditional SPF labeling. The second group received the same four free sunscreen options but with more explicit educational labeling that explained protection against sunburn and the harmful long-term effects of UV radiation. The third group served as control and received no intervention or free sunscreen. Data showed that both intervention groups wore sunscreen more than those who did not receive free sunscreen; those given the sunscreen with explicit labels yielded the best outcomes.15

Given that most US adults do not wear sunscreen, have adequate knowledge related to use of sunscreen, or receive appropriate guidance from healthcare providers with respect to sunscreen use, strategies to promote proper sunscreen use are warranted. To date, no intervention strategies effectively promote routine sunscreen use across populations.13 The current study examined the feasibility and efficacy of a novel intervention strategy to promote daily sunscreen use among adults.

Methods

Participants included college students (N=15 [males=2]) who were older than 18 years of age (Mage=22.47, SDage=8.79). Race demographics among the participants were as follows: 66.67 percent White (n=10), 13.33 percent Asian (n=2), 6.67 percent Black (n=1), 6.67 percent bi-racial (n=1), 6.67 percent other (n=1), and 6.67 percent Hispanic or Latino/x (n=1). All included participants self-reported wearing sunscreen twice weekly or less (on average) and did not have any known allergies to sunscreen ingredients or skin conditions that require prescription medication (topical and/or oral).

Sunscreen use eligibility and sunscreen knowledge questionnaires. A researcher-derived questionnaire was used to assess sunscreen use, apparent allergies to sunscreen ingredients, or skin conditions that require prescription medication. Further, a researcher-derived, seven-item sunscreen knowledge questionnaire was used to examine participant knowledge of sunscreen use and related outcomes (see Supplemental Materials).

Daily sunscreen use survey. Participants responded to the question, “Did you apply sunscreen to your face and neck today?” (Yes/No) daily.

Sunscreens. Sunscreen options (n=6) were SPF45 or higher and cost less than $20 USD for a full-sized bottle.12

Procedure screening and baseline. Participant recruitment occurred via university-wide bulk email including a link to an eligibility screener. Individuals who met inclusion criteria (N=206) were invited for an intake session, during which they completed informed consent (N=18). Three participants were disqualified—one for wearing sunscreen consistently during the baseline and two participants who provided insufficient data to remain in the study. After informed consent was received, participants entered a baseline phase (ranging 13 to 24 days) during which they completed daily sunscreen use surveys.

Sampling and selection. Upon completion of baseline, each participant attended an individual in-person sunscreen sampling session during which research assistants prepared blinded samples of six different sunscreens. Participants tested each sunscreen (i.e., one sunscreen sample on each of the following: left dorsal side of the hand, left upper and lower forearm, right dorsal side of the hand, right upper and lower forearm). After allowing the sunscreen to set for about 10 minutes, participants were asked to select three sunscreens from among the six samples to continue sampling. Research assistants prepared about one teaspoon of each of the three selected sunscreens in small aluminum tins and instructed participants to use each sample on the face and neck for the following six days (i.e., 1/2 of each one sample per day). All samples were blinded so that branding could not influence preferences. Participants were instructed to test the sunscreens with their typical self-care daily routines (e.g., after skincare, before makeup). After testing samples, participants were asked to identify which sunscreen they most preferred. Participants were provided a full-sized bottle of their preferred sunscreen to use post-intervention and asked to continue completing brief daily emailed surveys (ranging 9 to 27 days). All participants received daily contingent monetary compensation for data submission (regardless of sunscreen use) throughout the study (up to $26). Contingent bonus payments ($8) were made for submitting 85 percent or more of requested daily data.

Sunscreen use verification. A subsample of participants (n=5) was assigned randomly to provide daily video verification of sunscreen use for about two weeks following sunscreen selection. Participants attended a brief verification orientation session (via online video conference) during which contingencies related to verifying sunscreen use (1/4 tsp on face and neck) were explained. Participants provided video verification data using the TimeStamp application and shared their data via secure OneDrive folders. Participants in the verification subsample (n=5) received daily contingent monetary compensation for submission of video verification data confirming sunscreen use ($3/day and $14 for 85%+ data submission).

Data analysis plan. All data were analyzed using SPSS (Version 28.0). Frequencies, means, and standard deviations were used to describe sample demographics. Frequencies were used to examine days of sunscreen use during baseline compared to days of sunscreen use post-intervention and days of sunscreen use and verification for the individuals assigned randomly to provide video verification of sunscreen use. A dependent samples t-test was conducted to examine differences in mean numbers of days wearing sunscreen between baseline and post-intervention. All missing daily sunscreen use surveys and verification data were coded as having not worn sunscreen.

Results

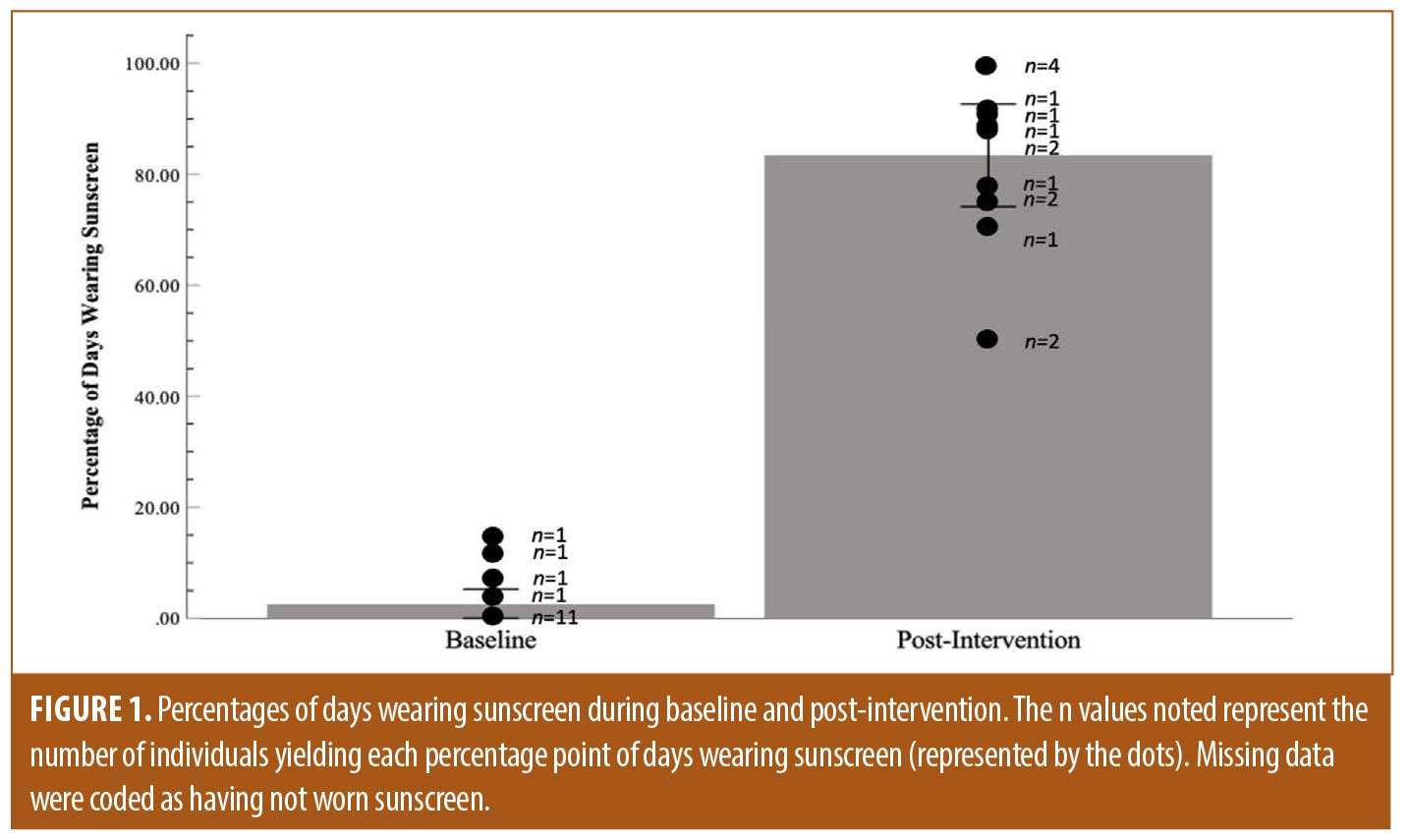

There were no differences between those screened (M=3.40, SD = 1.26) and those enrolled in the study (M=3.2, SD=1.42) with respect to knowledge. During baseline, participants reported wearing sunscreen on 2.60 percent of days (across all participants; 7/269 days). Following the S&S session, participants reported wearing sunscreen on 84.38 percent of days (across all participants; 216/256 days). A dependent t-test (t(14)=10.03, p<.001, d=2.60, observed power=0.999; see Figure 1) showed a difference in number of days using sunscreen between baseline (M=0.47, SD=0.92) and post-intervention (M=14.40, SD=4.75). The video verification sub-sample verified sunscreen application on 61.64 percent of days (45 of 73 days).

Discussion

Proper use of sunscreen is the most effective SC prevention strategy, such that sunscreen has been shown to prevent multiple forms of SC.3, 5 The current study examined the feasibility and initial efficacy of a novel S&S intervention strategy among young adults who do not regularly use sunscreen and had some sunscreen knowledge. Our findings suggest that allowing individuals to test sunscreen options and providing them with a bottle of sunscreen may increase their regular sunscreen use. We observed an increase in post-intervention sunscreen use among all participants.

Compared to past work, the current study intervention may be a viable and effective strategy for promoting regular sunscreen use. Past findings suggest modest increases in sunscreen usage (e.g., 12% increases from baseline14; and 25% difference compared to controls13) across various sunscreen strategies; our findings suggest approximately an 85-increase increase in days wearing sunscreen. A strength of our study is implementation of varying lengths of baseline and post-intervention periods (i.e., multiple-baseline design) across participants showing that regardless of when the intervention is introduced and for how long data were collected, sunscreen use increased post-intervention and was maintained throughout the study. We also blinded sunscreen samples to reduce the potential impact of branding and/or item costs on preference.16 Unpleasant side effects of use, such as breakouts, white cast, and shine, are a primary reason that individuals report not using sunscreen regularly.12 The S&S intervention allows individuals to identify sunscreens that do not yield commonly cited negative effects associated with sunscreen for them. Another reason that individuals report not wearing sunscreen is that they do not perceive a need for sunscreen12; an augment to the current study intervention may include educating individuals regarding the importance of and appropriate methods for wearing sunscreen. Though the study sample was imbalanced with respect to gender, the sample was comprised of about 33 percent of participants of color—a population of people who receive SC diagnoses later and related mortality is most prevalent.17

Limitations. Despite apparent intervention efficacy, various study limitations should be noted. For example, data were collected between January and May 2023; individuals may increase sunscreen use as temperatures and time spent outdoors increase; however, the screening assessment queried typical sunscreen use such that any use year-round should have been evident. Future work should examine S&S procedures across varied times and outdoor temperatures. Additionally, the current study relied primarily on self-report of sunscreen use; future studies should include verification of daily sunscreen use, such as UV cameras and video verification. Future research should also examine the effects of the S&S procedure with provision of free sunscreen compared to the S&S procedure without subsequent sunscreen provision, and/or compared to offering free sunscreen alone.

Given the lack of effective interventions to promote sunscreen use across populations, more work is needed to further examine the utility and acceptability of sunscreen S&S to promote sunscreen use. Future work may investigate verification of use in a larger, gender-balanced sample, in a sample of individuals who are at higher risk for SC, and/or across differing contexts or seasons of the year. Future work might also examine the utility of the S&S procedure as an augment to other strategies, such as education and contingency-based intervention, to promote sunscreen use. Study findings have implications for both healthcare and retail strategies.

Supplemental Materials

Irons Supplemental Questionnaire

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Melanoma of the skin statistics. Apr 18, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/statistics/index.htm

- Elfhein J. New melanoma skin cancer cases number by state U.S. 2023. Statista. February 3, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/663211/number-of-new-skin-cancer-cases-melanoma-in-the-us-by-state/

- Iannacone MR, Hughes NCB, Green AC. Effects of sunscreen on skin cancer and photoaging. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014; 30(2-3); 55– 61.

- Hung M, Beazer IR, Su S, et al. An exploration of the use and impact of preventive measures on skin cancer. Healthcare. 2022; 10(4); 743.

- Olsen CM, Wilson LF, Green AC, et al. How many melanomas might be prevented if more people applied sunscreen regularly? Br J Dermatol. 2018; 178(1); 140–147.

- Green AC, Williams GM, Logan V, Strutton GM. Reduced melanoma after regular sunscreen use: randomized trial follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29(3); 257–263.

- Gordon LG, Scuffham PA, Van Der Pols JC, et al. Regular sunscreen use is a cost-effective approach to skin cancer prevention in subtropical settings. J Invest Dermatol. 2009; 129(12); 2766–2771.

- Philips M. Realself report: 62% of Americans use anti-aging products daily, but only 11% wear sunscreen daily. RealSelfNews. https://www.realself.com/news/2020-realself-sun-safety-report

- Wang SQ, Dusza SW. Assessment of sunscreen knowledge: a pilot survey. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 161(s3); 28–32.

- Low QJ, Teo KZ, Lim TH, et al. Knowledge, attitude, practice and perception on sunscreen and skin cancer among doctors and pharmacists. Med J Malaysia. 2021; 76(2), 212–217.

- Vasicek BE, Szpunar SM, Manz-Dulac LA. Patient knowledge of sunscreen guidelines and frequency of physician counseling: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018; 11(1); 35.

- Diehl K, Schneider S, Seuffert S, et al. Who are the nonusers of sunscreen, and what are their reasons? Development of a new item set. J Cancer Educ. 2021; 36; 1045–1053.

- Allen N, Damian DL. Interventions to increase sunscreen use in adults: a review of the literature. Health Educ Behav. 2022; 49(3): 415–423.

- Mallett KA, Turrisi R, Billingsley E, et al. Evaluation of a brief dermatologist-delivered intervention vs usual care on sun protection behavior. JAMA Dermatol. 2018; 154(9);1010–1016.

- Nicol I, Gaudy C, Gouvernet J, et al. Skin protection by sunscreens is improved by explicit labeling and providing free sunscreen. J Invest Dermatol. 2007; 127(1); 41–48.

- Prado G, Ederle AE, Shahriari SR, et al. Online sunscreen purchases: impact of product characteristics and marketing claims. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2019; 35(5); 339–343.

- Gupta AK, Bharadwaj M, Mehrotra R. Skin cancer concerns in people of color: risk factors and prevention. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016; 17(12); 5257.