J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(1):24–27

by Victoria Comeau DO, PGY II; Marcus Goodman, DO; Mary Margaret Kober, MD; and Christopher Buckley, DO

by Victoria Comeau DO, PGY II; Marcus Goodman, DO; Mary Margaret Kober, MD; and Christopher Buckley, DO

Drs. Comeau, Goodman, and Buckley are with the Department of Dermatology at Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine in Roswell, Georgia. Drs. Goodman, Kober, and Buckley are also with Goodman Dermatology in Roswell, Georgia.

Funding: No funding was received for this case report.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Rhinophyma is a progressive, disfiguring condition that affects the nose and is caused by the hypertrophy of sebaceous glands and connective tissue. Although its exact pathogenesis remains unclear, it is generally thought to be a subtype of the chronic, inflammatory condition rosacea. To date, oral and topical treatments have been largely ineffective at treating rhinophyma. Laser resurfacing is an emerging treatment modality that offers hope for patients with severe rhinophyma. We present a case of rhinophyma treated via fractionated carbon dioxide laser resurfacing with impressive results, excellent tolerability, and minimal downtime.

Keywords: Rhinophyma, phymatous rosacea, rosacea, carbon dioxide laser, fractionated carbon dioxide laser

Over the past few decades, severe rhinophyma has remained one of the simplest diagnoses to make, yet is one of the most difficult conditions to treat. Rhinophyma is the progressive hypertrophy of sebaceous units and eventual distortion of facial tissue overlying the nasal region. The condition is considered a variant of phymatous rosacea, which is a subtype of the chronic, inflammatory condition rosacea. However, while rosacea is most commonly seen in middle-aged women, rhinophymatous variation of rosacea most commonly affects men.1 Multiple theories have been suggested regarding the pathogenesis of rosacea, including dysfunction of the innate immune system, sensitivity to bacterial antigens produced by Demodex mites, and even chronic ultraviolet radiation exposure; however, a lack of consensus remains.1

Various treatment modalities have been proposed to treat this disfiguring condition. Historically, topical medications and oral anti-inflammatory agents have done little to counteract its unrelenting nature. In more recent years, modern treatment modalities, such as electrosurgery and laser resurfacing, have given hope to patients with rhinophyma, as they produce significant cosmetic results with infrequent adverse effects and minimal downtime.1,2,4,6,7,8,12

We present a case of a patient suffering from severe rhinophyma who underwent fractionated CO2 laser resurfacing therapy. This case was selected in an effort to highlight the striking cosmetic and functional improvement our patient experienced. The tolerability of the procedure in combination with the reasonable recovery and dramatic results support the use of fractionated CO2 laser resurfacing in future rhinophyma cases.

Case Presentation

A 71-year-old man with a longstanding history of rosacea presented to our clinic in search of options to improve the appearance of his enlarging nose. Prior to presenting to our office, the patient had treated his rosacea with topical medicated washes and over-the-counter products. His initial clinical examination revealed telangectasias, significant erythema, and scattered papules with large pores. Severely irregular contour of the nasal architecture was noted as well. At his initial visit, he was started on oral doxycycline hyclate 100mg twice daily and topical metronidazole 0.75% cream.

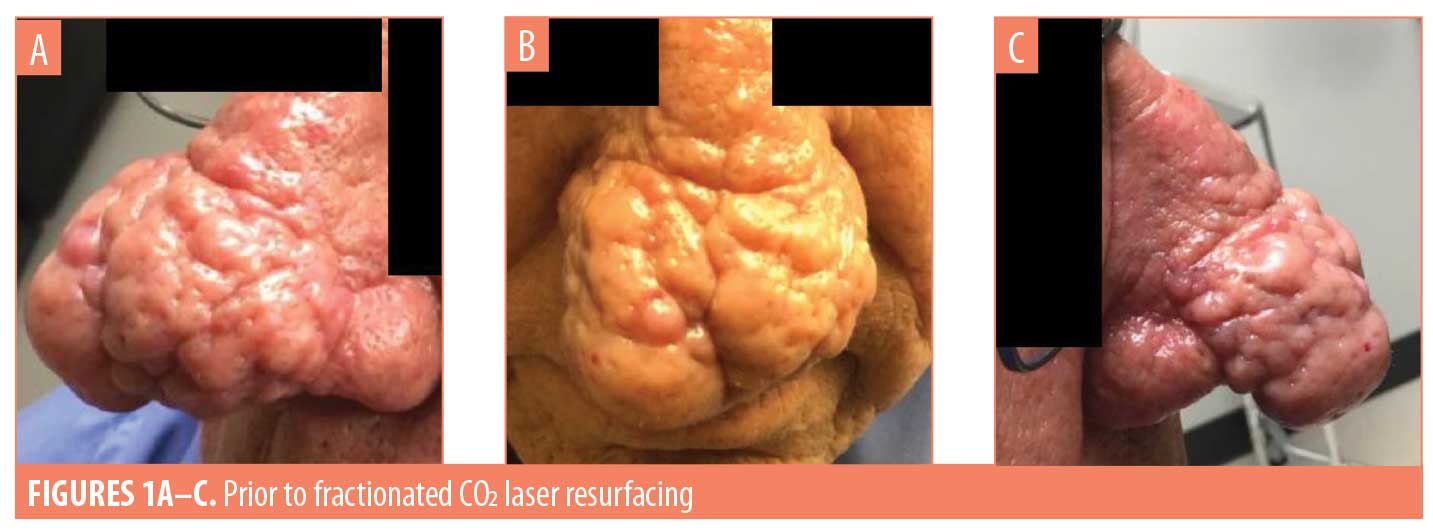

Over the next seven months, the patient was adherent with his treatment regimen; however, he continued to experience substantial rosacea flares and drastically worsening nasal hypertrophy. In an aggressive effort to control his condition, an inclusive oral and topical treatment plan was established. He was changed to oral minocycline 105mg daily and was continued on topical metronidazole 0.75% cream. He was additionally started on topical ivermectin 1% and topical azelaic acid 15%. Although his overall rosacea clinically stabilized, he demonstrated impressively severe, progressive rhinophymatous changes (Figures 1A–C). The patient was then referred for fractionated CO2 laser resurfacing.

The patient underwent initial laser resurfacing in which a dermal optical thermolysis (DOT) fractionated CO2 laser (SmartXide, DEKA Medical Inc., San Francisco, California) was utilized. He received prophylaxis with valacyclovir 500mg twice per day for five days beginning on the day of the procedure. His nose was prepped with chlorohexidine solution. He was anesthetized using injected lidocaine with epinephrine in addition to topical benzocaine/lidocaine/tetracaine cream. All appropriate laser precautions were taken prior to starting the procedure. The panel was set to 30 W with a dwell time ranging from 4,000 to 7,000 microseconds and a pitch of 200 micrometers. Approximately 18 to 20 passes were performed over the highly sebaceous areas of the nose, while the less sebaceous areas were treated with fewer passes. The procedure was tolerated well with no complications. After the procedure, petrolatum and an occlusive dressing were applied. Wound care instructions were reviewed with the patient. The patient washed the area twice per day and reapplied emollients multiple times per day. The patient did not require pain management medication.

The patient was seen at two weeks postprocedure. Residual erythema was present on physical examination. A significant improvement was noted, and he was satisfied with the results. He restarted oral minocycline 105mg daily and topical metronidazole 0.75% cream.

The patient was seen again at eight weeks postprocedure. A significant improvement was noted in rhinophymatous changes and the patient reported being “very pleased” with his results. A small cyst was noted on the nose, which was subsequently treated with intralesional triamcinolone 5.0mg/cc. He was continued on oral minocycline 105mg daily as well as topical ivermectin. He was started on topical sodium sulfacetamide 9.5%/sulfur 5% wash. He also received a single 12-mg dose of oral ivermectin.

Twelve weeks after the initial fractionated carbon dioxide laser resurfacing treatment, the patient underwent a second treatment with the SmartXide DOT fractionated CO2 laser to further contour the nose. Images were obtained prior to the procedure (Figures 2A–C). He received the same prophylaxis and anesthesis that was administered prior to the first procedure. Laser settings were as follows: power, 25 W; dwell time, 4,000 microseconds; and pitch, 350 micrometers. Ten to 12 passes were performed on the residual hypertrophic sebaceous tissue, with significant blending into the normal tissue. The procedure was well tolerated with no complications. Wound care was performed as previously stated.

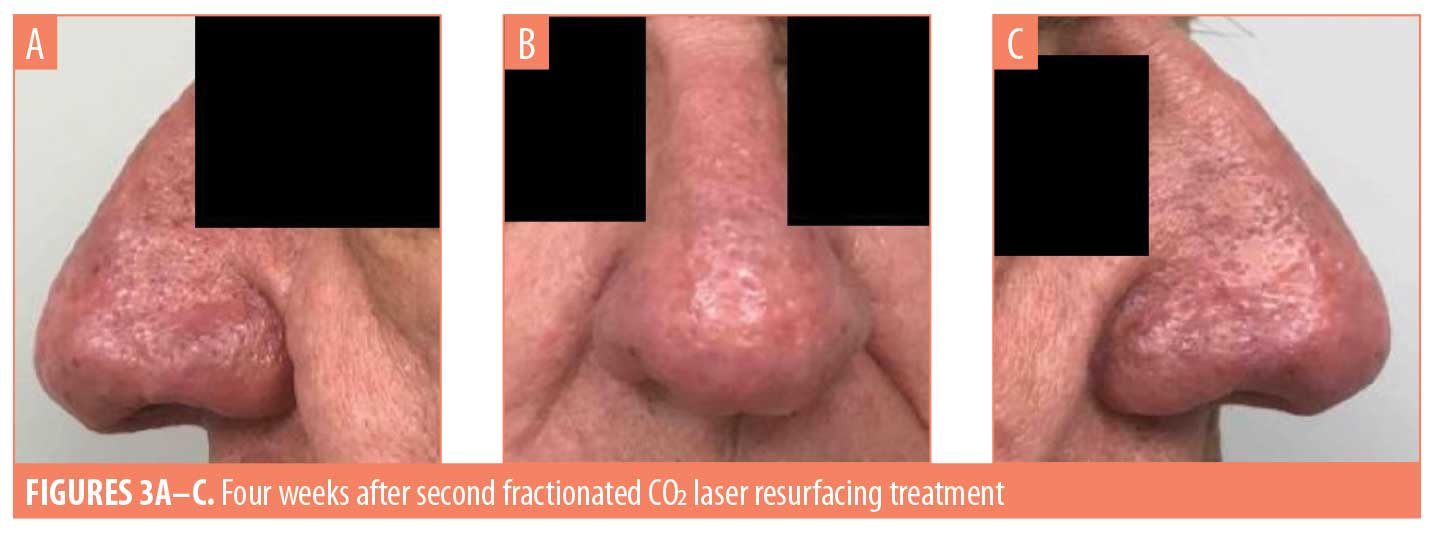

The patient was seen one week after this second procedure, and healing appeared to be within normal limits. At four weeks after the procedure, the healing process was complete and clinical examination revealed remarkable improvement in nasal texture and contour (Figures 3A–C). The patient was very satisfied with the results.

The patient has since continued his treatment regimen of oral doxycycline monohydrate 40mg daily and topical sodium sulfacetamide 9.5%/sulfur 5% wash. Tretinoin 0.05% cream was also added to this regimen. The patient was last seen at 12 weeks after the second procedure. He remained quite satisfied with his final results, reporting a drastic improvement in his quality of life. No evidence of unsatisfactory scarring or dyspigmentation was observed at that time.

Discussion

Rosacea is a common and chronic condition treated in the dermatologist’s office on a daily basis. Its pathogenesis remains unclear, although multiple conceivable theories exist. Some authors suggest the condition is a result of a dysfunctional innate immune system that results in an inappropriate upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and angiogenic substances.1 Other theories postulate that chronic ultraviolet radiation exposure results in free radicals, blood vessel damage, and resultant angiogenesis.1 Less popular theories exist proposing a sensitivity to the bacteria accompanying Demodex mites, which is reinforced by research demonstrating higher counts of Demodex mites present in the skin of rosacea patients.1,2 It has additionally been suggested that Helicobacter pylori might play a role.3 Further research into the pathogenesis of rosacea would ideally reveal a single, treatable pathway; however, it is far more likely that the etiology is multifactorial.

Rosacea is seen primarily among those with fair skin types and most commonly in female patients between the ages of 30 and 50 years. There are four major subtypes of rosacea: erythematotelangectatic, papulopustular, ocular, and phymatous. The erythematotelangectatic type is characterized by flushing, erythema, and prominent blood vessels and is worsened by triggers including alcohol, heat, and emotion. The papulopustular type is characterized by erythema in the central facial region accompanied by erythematous papules with or without accompanying pustules. The ocular type is characterized by irritation, itching, and tearing.1,3

Phymatous-type rosacea is characterized by hypertrophy of the sebaceous glands, edema, and distortion in tissue contour.1 It is subdivided according to facial location affected: specifically, rhinophyma involves the nose, metophyma involves the forehead, blepharophyma involves the eyes, otophyma involves the ears, and gnatophyma involves the chin.1 Unlike classic rosacea, which typically affects women, rhinophyma typically affects an older subset of the Caucasian male population aged 50 years to 70 years.4,5 While some researchers theorize that rhinophyma is an end-stage of rosacea, others believe it exists as an independent entity.1,4,6,9,11

Numerous treatment modalities have been considered to treat the debilitating aesthetic and functional changes of rhinophyma. A review of the current literature reveals a consensus that topical antibiotics, topical retinoids, and systemic antibiotics have proven largely ineffective, leaving surgical intervention, including CO2 laser surgery, as the mainstay of treatment.1,2,4,6,7,8,9

Excision of involved tissue, including both partial-thickness and full-thickness excision, has been a classic approach to rhinophyma treatment.2,4,6 While it has been historically successful, new technologies offer increasingly efficacious treatment options with superior cosmetic results, therefore decreasing the popularity of classic excision.

Radiotherapy was another early treatment approach for rhinophyma. However, it quickly fell out of use due to the increased risk of malignancy in the treated tissue.4,7

Cryosurgery for rhinophyma treatment was developed within the past few decades. This modality was inexpensive and produced minimal bleeding; however, major disadvantages have been noted, including the inability to control the depth of thermal damage and unsatisfactory discoloration.5

Electrosurgery and electrocautery have also made their way into the rhinophyma treatment literature. In a study presented by Rordam et al,8 three patients were successfully treated with electrosurgery via wire loop. The patients experienced satisfactory cosmetic results with reepithelialization occurring within two weeks. In that study of three patients, no significant pain, scarring, or dyspigmentation was noted. However, while treatment using electrocautery offers minimal bleeding as a key benefit, there exists a significant risk for deep thermal injury and scarring.4,5

The role of lasers in the treatment of rhinophyma has gained popularity throughout recent years. Erbium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet lasers, diode lasers, and argon lasers have been mentioned in literature; however, CO2 laser resurfacing is at the forefront of rhinophyma therapy.2,5–7 CO2 laser resurfacing can be performed under general anesthesia or local anesthetic, the latter of which might be preferred by the patient as an in-office treatment option. In one study comparing four patients who each underwent fully ablative CO2 laser resurfacing, two patients received general anesthesia while two received local anesthesia. It was notable that there was no difference in procedural outcomes or satisfaction.6 While general anesthesia remains an option, it is important to recognize the effectiveness, cost-efficiency, and impressive safety profile of local anesthetics.

The literature suggests that laser resurfacing results in minimal bleeding, making it a favorable working environment for the user.2,4 One study published by Cravo et al6 found that utilizing a combination of fully ablative CO2 laser with bipolar electrodessication achieved better results in ideal hemostasis. The patients maintained rapid reepithelialization as well as minimal scarring without any documented postoperative complications.

Unlike many of the alternative treatment modalities, CO2 laser boasts the ability to precisely control the depth of injury.4 The depth of thermal damage is exact, noted to be 0.5mm below the charred zone in one study involving the use of fully ablative carbon dioxide laser; the bloodless environment also allows for the additional assurance of correct depth as sebum is released from sebaceous glands as a result of the thermal injury.9 In addition, the CO2 SmartXide laser, the device used in our case report, is commonly incorporated in superpulse mode, which is noted to produce a consistent leveling of treated regions to the target thickness.10 Although superpulse mode was not used in our patient, it might be of benefit when applying this particular laser to treat rhinophyma.

Procedural outcomes using laser resurfacing for the treatment of rhinophyma have been impressive. In a single study of 124 patients who underwent CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma, 96 percent rated their satisfaction as at least a seven out of 10 and 77 percent rated their satisfaction as a 10 out of 10.9 This particular study utilized a fully ablative CO2 laser in continuous mode for debulking purposes and resurfacing mode for reshaping purposes. It is noteworthy that 92 percent of patients reported that they would recommend the treatment to others suffering from rhinophyma.

Another study examined five patients diagnosed with mild-to-moderate rhinophyma who underwent a single treatment of fractionated CO2 laser therapy.11 All patients tolerated the procedure well and experienced significant improvements in size, shape, and tissue texture of the treated regions. A similar report involved three patients, each diagnosed with mild rhinophyma, who also underwent treatment with a fractionated CO2 laser. Two of three patients were reported to have significant improvements in sebum excretion, pustules, erythema, and thickening. All three patients tolerated the procedure well, and no permanent scarring or dyspigmentation occurred.12

In addition to satisfactory cosmetic results, other benefits of CO2 laser therapy include rapid reepithelialization starting as early as four days post-procedure, with resolution typically occurring within 3 to 6 weeks post-procedure with relatively mimimal pain.2,4,6,11 The wide range of reepithelialization is likely attributable to the variation in laser settings, as well as the use of fractionated ablative CO2 laser in some studies, compared with the use of fully ablative CO2 laser in others. In the previously described case series,12 all three patients were treated with fractionated ablative CO2 laser, with complete reepithelialization occurring within one week post-procedure.12

Fractionated ablative CO2 lasers create microthermal zones, leaving uninjured columns of healthy tissue that aid in healing.1 This process results in faster healing times and fewer adverse effects than traditional fully ablative CO2 laser therapy.10,11,12 In a study performed by Serowaka et al,11 the authors reported that the fractionated ablative CO2 laser used in the study resulted in an overall “more natural” result.

As with any surgical procedure, significant risks exist. One of the most notable considerations is scarring, most commonly involving the nasal ala.9 Another potential disadvantage includes dyspigmentation, specifically hypopigmentation,2,9 which can develop up to six months postprocedure.9 Post-treatment pallor following fully ablative CO2 laser treatment is a considerable concern and should be taken into careful consideration when choosing a fully ablative CO2 laser.13 Extra caution must be employed when treating advanced Fitzpatrick skin types, as the risk of dyspigmentation is substantial.1 Additional considerations include the advanced training required to perform CO2 laser resurfacing as well as the expense of the technology itself.2,4,5

Limitations. This case report was on a single patient, which limits our conclusions. Additionally, the follow-up period for our patient did not extend beyond 12 weeks postprocedure, which also limits our conclusions. Additional research with a larger number of subjects in a controlled setting will be needed to support our findings.

Conclusion

Despite recent significant technological advances in treatment options, rhinophyma remains a challenging condition to treat. Among a multitude of treatment modalities, fractionated CO2 laser resurfacing is an innovative in-office treatment option that has been shown to achieve desirable cosmetic outcomes with excellent tolerability and minimal downtime.

References

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al. Rosacea and related disorders. In: Powell FC, Raghallaigh SN, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2009: 561–569.

- Lomeo PE, Mcdonald J, Finneman J. Rhinophyma: treatment with CO2 laser. Ear Nose Throat J. 1997;76(10):740–743.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, Neuhaus IM. Acne. In: Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016: 239–241.

- Sadick H, Goepel B, Bersch C, et al. Rhinophyma: diagnosis and treatment options for a disfiguring tumor of the nose. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61(1):114–120.

- Redett RJ, Manson PN, Goldberg N, et al. Methods and results of rhinophyma treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(5):1115–1123.

- Cravo, M, Canelas MM, Cardoso JC, et al. Combined carbon dioxide laser and bipolar electrocoagulation: another option to treat rhinophyma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20(3): 146–148.

- Fink C, Lackey J, Gradne D. Rhinophyma: a treamtent review. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(2): 275–282.

- Rordam OM, Guldbakke K. Rhinophyma: big problem, simple solution. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011; 91(2):188–189.

- Madan V, Ferguson JE, August PJ. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of rhinophyma: a review of 124 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(4):814–818.

- Campolmi P, Bonan P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Highlights of thirty-year experience of CO2 laser use at the Florence (Italy) department of dermatology. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:546528.

- Serowka KL, Saedi N, Dover JS, Zachary CB. Fractionated ablative carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of rhinophyma. Lasers Surg Med. 2014;46(1):8–12.

- Meesters AA, van der Lindent M, De Rie MA, Wolkerstorfer A. Fractionated carbon dioxide laser therapy as treatment of mild rhinophyma: report of three cases. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28(3): 147–150.

- Madan V. Dermatological applications of carbon dioxide laser. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6(4): 175–177.