J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2025;18(6):22–25.

by Nadine A. Del Rosario, BS; Shayla H.U. Nguyen, BS; and Ethan Q.H. Nguyen, MD

Ms. Del Rosario and Dr. Nguyen are with the University of California at Riverside School of Medicine in Riverside, California. Ms. Nguyen is with the University of California Riverside, in Riverside, California. Dr. Nguyen is also with RainCross Dermatology in Riverside, California.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH) is a rare pustular psoriasis variant that presents as sterile pustules on the hands and feet with a relapsing course. This condition is not easily treated, but literature shows some cases are successfully controlled with biologics such as etanercept, adalimumab, secukinumab, and ustekinumab. Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) is a type of autoimmune disease and is rarely seen in the pediatric population. It is characterized by overlapping features of various autoimmune disorders, often involving scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, polymyositis, and other organ dysfunction. MCTD is typically diagnosed with lab testing to indicate the presence of specific autoantibodies to a nuclear matrix protein, such as ribonucleoprotein. This communication emphasizes the importance of revisiting diagnoses in patients with persistent, refractory skin conditions and highlights the need for comprehensive evaluation in the presence of evolving or atypical presentations, especially when autoimmune diseases are suspected. Steps for diagnostic workup and treatment may provide clinical benefits to patients and serve as a reference for other clinicians. The course of treatment for ACH and MCTD in the pediatric and adolescent population is discussed. Keywords: Acrodermatitis continua, acrodermatitis perstans, dermatitis repens, mixed connective tissue disease, overlapping autoimmune disease

Introduction

A 20-year-old female with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) presented to a dermatology clinic after having ongoing severe hand and foot lesions prominent on her dorsal distal fingers and toes. She was initially evaluated at nine years old when symptoms began with severe cracking and bleeding of her fingers/toes along with jagged, malformed, and tender nails. This interfered with schoolwork, exacerbated her ADHD, and a diminished quality of life due to her isolation from some classroom activities and her learning disability. At the time, the patient was diagnosed with acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau. Subsequently, she was treated with tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) inhibitors, etanercept and adalimumab, with no improvement. She was lost to follow-up and decided to get reevaluated over 10 years later.

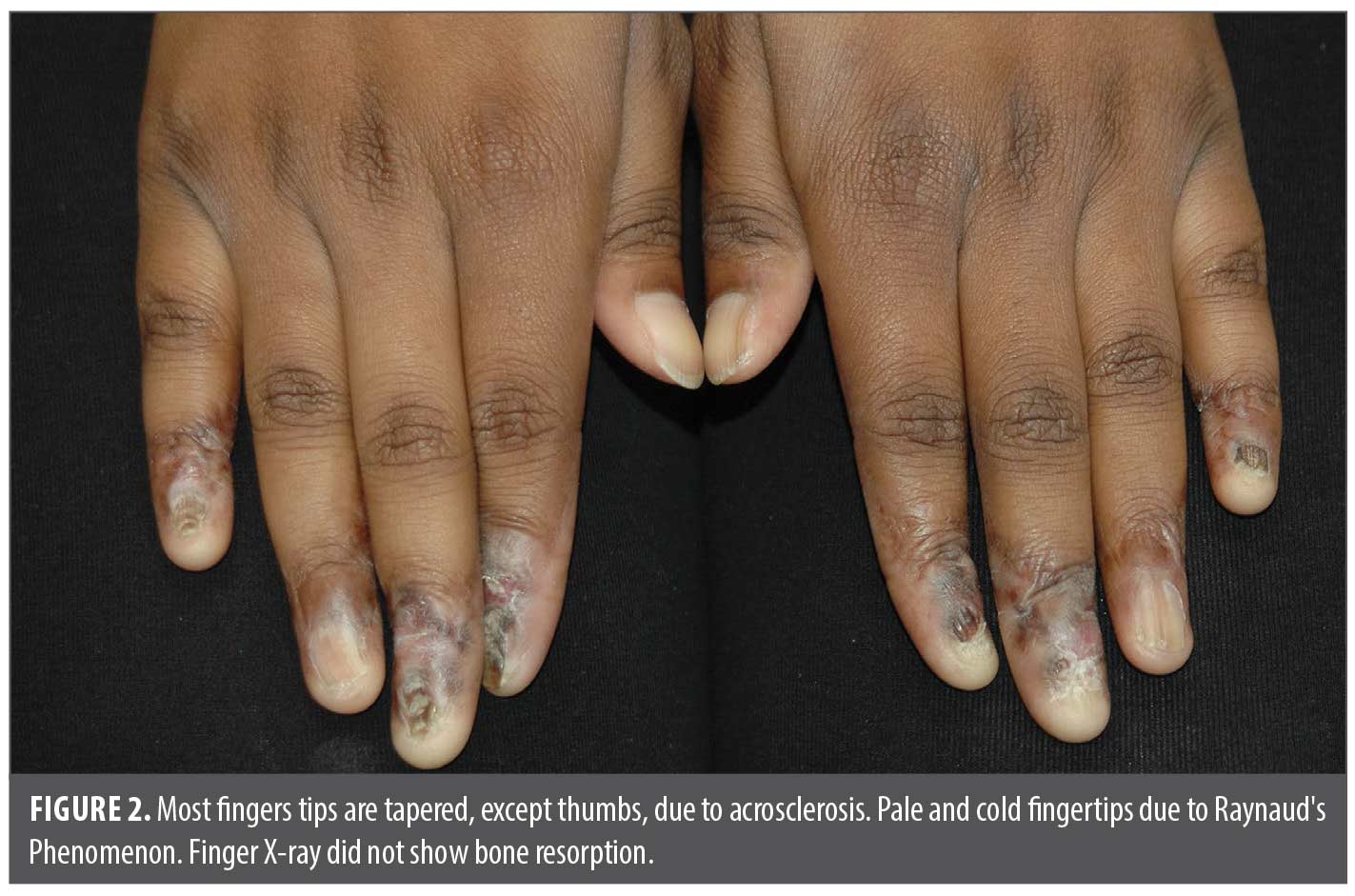

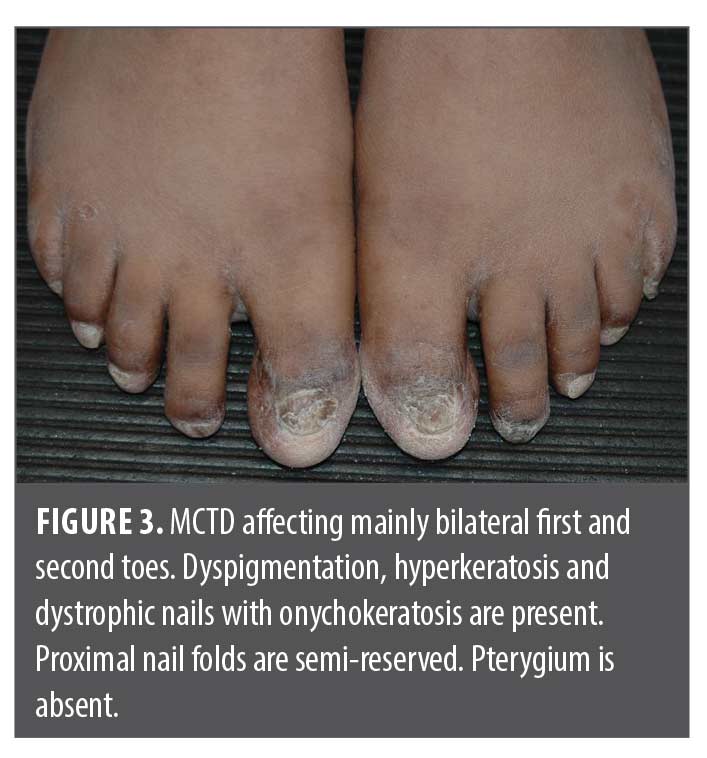

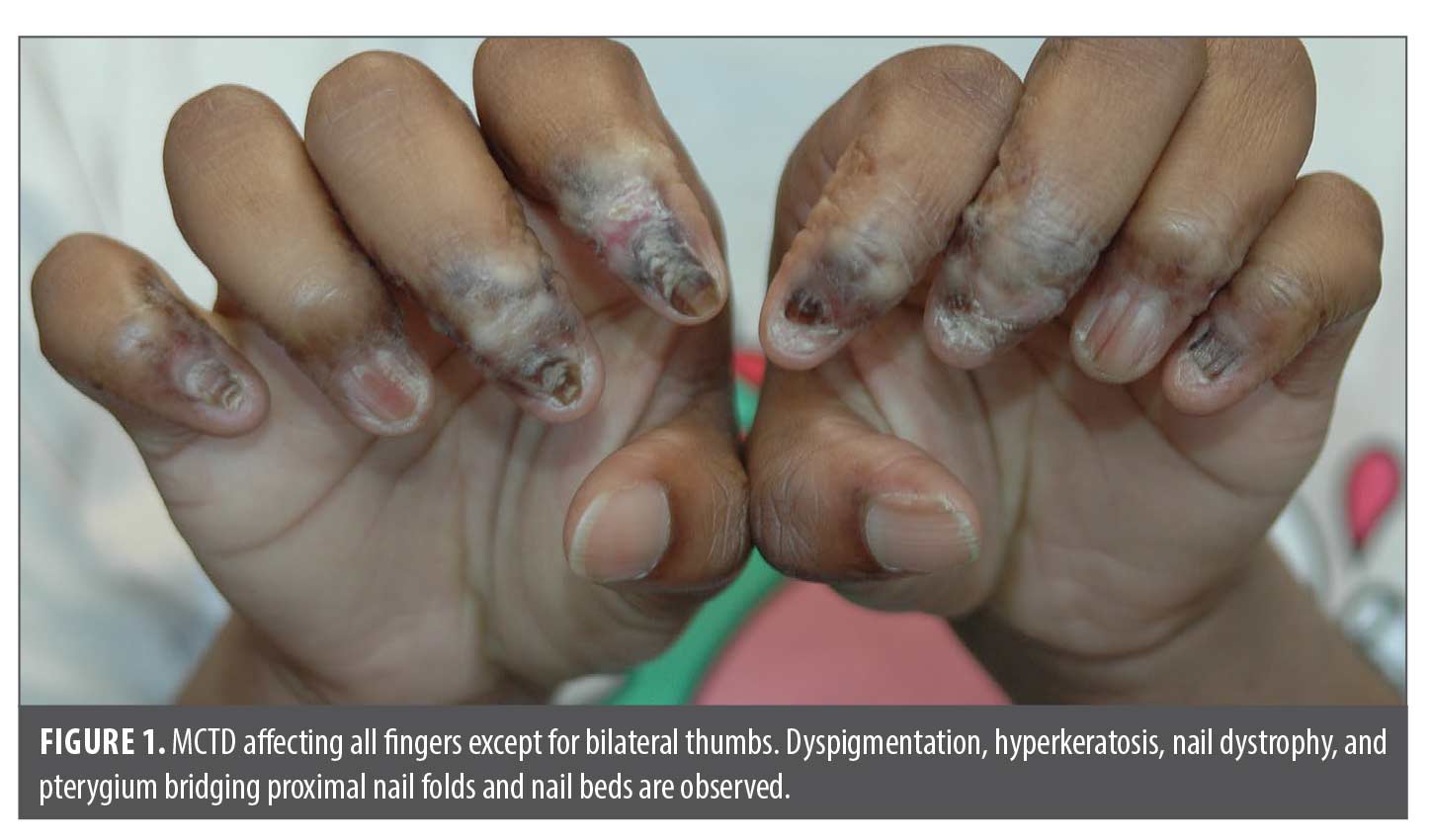

In 2022, she presented as an adolescent in our dermatology clinic with hyper- and hypopigmented atrophic patches involving dorsal distal fingers/toes, obliteration of proximal and lateral nail folds with pterygium formation bridging the proximal fingernail folds and nail beds. Fingernail plates were jagged and dystrophic with horizontal and longitudinal cracks, ridging and lifting of medial edges similar to “angel-wing” deformity. Some fingers have anonychia (Figures 1 and 2). Only bilateral thumbs appeared normal, and capillary loops of proximal nail folds were absent. Toes were affected to a lesser extent (Figure 3). All distal fingers were pointed, pale, and cold. The differential diagnosis included psoriasis, atypical lichen planus, and scleroderma. Punch biopsies were performed of the right third dorsal distal finger and left third proximal fingernail bed. Histopathology revealed superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrates, interface dermatitis, dermal fibrosis, and prominent mucin, favoring mixed connective tissue disease with combined features of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and scleroderma. Laboratory tests, including ANA (<1:80), anti-dsDNA, Scl-70, SS-A, SS-B, anti-Smith, anti-RNP, CRP, ESR, and RF were all negative. Electrolytes, hepatic and renal function, and C3+4 were within normal limits. The patient had iron deficiency and microcystic anemia per complete blood count. X-rays of hands and fingers showed no significant bone, joint or soft tissue abnormality.

Discussion

Diagnostic challenges and evolution of the disease. In 1890, Francois Henri Hallopeau described a painful acral pustular syndrome now known as acrodermatitis continua, dermatitis repens or acrodermatitis perstans.1 It is a rare, chronic variant of pustular psoriasis that primarily affects the distal fingers and toes most commonly in middle-aged women. In the population of people diagnosed with ACH, about 80 percent begin in only one digit, most commonly the thumb.1 The disease is essentially unilateral in the beginning and remains asymmetric throughout its entire course. It presents with sterile pustules, erythema, scaling, paronychia, nail dystrophy, and severe pain, often leading to functional impairment, significant morbidity, and skin atrophy with underlying soft tissue sclerosis and possible bone resorption.1–3 Histological features show intraepithelial spongiform neutrophilic pustules (of Kogoj), psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, and parakeratosis.3 This condition predominantly targets the dorsal aspects of distal phalanges and can permanently damage the affected digits if untreated or unresponsive to therapy. Breached skin barrier is further complicated by bacterial infection, which responds slowly and poorly to antibiotic therapy.3

Prior to availability of biologics, systemic corticosteroids provide improvement, but severe exacerbation occurs upon withdrawal of the drug. Etretinate (no longer available in United States) and acitretin were found effective in controlling the condition.3 Research gains some progress with identifying 16 genetic mutations as a cause of 20 percent of ACH cases. IL-36RN mutations result in defects in IL-1 signaling, and agents like anakinra (IL-1 antagonist) have been reported successful in treating ACH.2,4 Optimal treatment may require developing agents that specifically target IL-36 (ie, spesolimab) or common pathways between IL-1 and IL-36. Genetic studies have also uncovered variants in other genes among patients with ACH, such as CARD1421 and AP1S3.2 These findings hint a more complicated genetic picture to this disease beyond IL36RN and the need to develop more targeted treatment options.

The diagnosis of ACH in children is rare, with limited literature addressing its management in pediatric populations.4 ACH can be particularly debilitating in pediatric patients, where the impact on daily activities and schoolwork can compound comorbid conditions, such as ADHD and social isolation. Overlapping symptoms, particularly the severe nail involvement, make distinction of ACH from other dermatological or autoimmune conditions difficult. Early diagnosis is crucial in preventing irreversible damage to the digits, yet this case demonstrates how long-term follow-up and reevaluation are critical in cases where standard treatments fail.

The initial diagnosis of ACH in this case, supported by clinical presentation, led to an updated therapeutic regimen involving TNF-α inhibitors. These biologics are commonly used in treating psoriasis, including pustular variants, and have shown efficacy in reducing inflammation and controlling symptoms in many patients.2 However, lack of response to both TNF-α inhibitors suggests the possibility of a different etiopathogenesis. In such as case, repeating workup should be considered.

Clinical findings of Raynaud’s Phenomenon, inflammatory scarring manifested as skin atrophy, obliteration of nail folds, pterygium, post-inflammatory dyspigmentation, and associated nail dystrophy all pointed to chronic destructive inflammatory process usually nonreversible. This is particularly true in DLE or scleroderma. In psoriasis, after inflammation subsides skin tissue and nails usually recover with minimal permanent scarring. New data from biopsy findings significantly supported a change of the diagnosis from ACH to MCTD in this case.

Refractory ACH and underlying autoimmunity. MCTD was first described by Sharp et al in 1972.5 It is characterized by overlapping features of various autoimmune disorders, often manifesting Raynaud’s Phenomenon (universally observed in all patients), polyarthritis, scleroderma, dermatomyositis, lupus erythematosus, hematologic, cardiac, pulmonary, renal, and gastrointestinal abnormality.5–7 Diagnostic criteria include high titers of antibodies against U1RNP (IgG serotype confers 100% sensitivity) and the presence of at least 3 of 5 of the following features: edema of hands, synovitis, myositis, Raynaud’s Phenomenon, and acrosclerosis.7–10 Nevertheless, seronegative MCTD has been reported.11 Other terms, undifferentiated connective tissue disease or overlapping autoimmune syndromes, have been proposed but did not gain popularity in the literature. While one-quarter of MCTD transform into LE, the other one-third progress to systemic sclerosis. Causes of death include advanced pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), interstitial lung disease, infections, and cardiopulmonary failure.8

MCTD is rare in children. Based on two small pediatric cohort studies,12,13 mean age at diagnosis is about 11 years old. Clinical symptoms change with time and other encompassing criteria eventually develop. Inflammatory manifestations improve with treatment but sclerodermatous features (sclerodactyly, esophageal dysmotility/stricture, and vasculopathy) tend to persist and be unresponsive to therapy. Sclerotic changes of internal organs are a poor prognostic factor.13 Organ involvement escalates over time with a worsening rate of 15 to 20 percent per 3 to 5 years. A quarter of children have symptomatic PAH.12

The eventual diagnosis of MCTD in this patient underscores the complexity of autoimmune overlap syndromes, particularly when dermatological manifestations dominate the clinical picture. It can present with diverse cutaneous symptoms, including those resembling psoriasis. The delayed diagnosis argues that the initial presentation of ACH may have been an early, mischaracterized manifestation of an underlying autoimmune process, complicating both the clinical picture and treatment approach.

This case also demonstrates the importance of performing skin biopsy and histopathological analysis in cases of treatment-resistant skin conditions. Histologic findings can differentiate between ACH and MCTD. The authors were quite surprised that most rheumatology literature cited the diagnostic criteria for MCTD rarely recommend or include skin biopsies of the affected skin lesion to provide additional data.14,15 The presence of both DLE and scleroderma features suggests that the patient’s early ACH appearance mimicked cutaneous manifestation of a broader autoimmune disorder, which eventually evolved into MCTD over time. Misdiagnoses in the pediatric population are not uncommon in rare dermatologic conditions, and the evolution of the patient’s disease process over times accentuates the need for continuous reassessment when treatments fail.

Therapeutic implications. The refractory nature of this patient’s ACH diagnosis, despite the use of TNF-α inhibitors, stresses the challenge of managing rare pustular psoriasis variants in the presence of an underlying autoimmune disorder. While TNF-α inhibitors are effective for many psoriasis subtypes, including ACH, their efficacy in autoimmune overlap syndromes like MCTD is more limited. In cases of autoimmune overlap, treatment may require a combination therapy of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents that target a broader range of inflammatory pathways.6,8 Based on the diagnostic change, the transition from biologic therapy to immunosuppressive treatments (ie, corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mofetil mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporin, or azathioprine) to manage MCTD reflects the need for a more comprehensive approach in such cases. This patient was given hydroxychloroquine 200mg PO BID. At the six-month follow-up, the inflammatory edema and scaling of most fingers improved. Nail beds had less hyperkeratosis, and some nail plates partially regrew. Bilateral fourth fingers showed remarkable recovery with normalization of the proximal nail folds and nail plates (Figures 4 and 5).

It has been reported that MCTD patients initially diagnosed without pulmonary arterial hypertension subsequently developed proximal nail fold capillaries (41.3%) and PAH if not being treated, indicating progression of vasculopathy in the etiopathogenesis of MCTD.10 Endothelial receptor antagonists are recommended when microvascular involvement and PAH are present to prevent morbidity and death. Moreover, nail fold capillaroscopy could be a useful tool to predict the coexistence of PAH.10 We plan to monitor the patient long-term for the development of other MCTD systemic symptoms and have both rheumatology and pulmonology assist us.

Conclusion

This case highlights the complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in managing refractory ACH in a pediatric patient, particularly when the condition masks an underlying autoimmune disorder. Despite the initial diagnosis of ACH and treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) inhibitors, the refractory nature of the patient’s symptoms prompted further investigation, ultimately leading to the identification of MCTD. Early recognition of treatment resistance, utilizing biopsy to confirm or reassess the diagnosis, is crucial.

MCTD is rare in pediatric populations, and its coexistence with dermatologic manifestations, such as those initially resembling ACH, highlights the need for ongoing diagnostic vigilance. In this case, repeated clinical and histopathological assessments were critical for identifying the transition from ACH to MCTD. The overlap between the two conditions, as evidenced by the patient’s refractory response to treatments and the histological findings indicating DLE and scleroderma, suggests that ACH may have been an early cutaneous manifestation of MCTD, complicating both diagnosis and treatment. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for autoimmune overlap syndromes in patients with chronic or atypical presentations of dermatologic diseases, ensuring that diagnostic and treatment strategies are adjusted as the clinical picture evolves to prevent severe systemic organ dysfunction from accruing, influencing disease prognosis and mortality.

The patient’s improvement following the switch to hydroxychloroquine therapy further emphasizes the importance of adjusting treatment protocols based on evolving diagnostic insights. This case advocates for a broader therapeutic approach when faced with treatment-resistant dermatologic conditions in pediatric patients, especially in those with potential underlying autoimmune conditions. Long-term monitoring for the development of other systemic MCTD features, including pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), remains essential, with a multidisciplinary approach involving dermatology, rheumatology, and pulmonology.

Future studies and case reports are necessary to further delineate the relationship between ACH and autoimmune overlap syndromes, as well as to identify more targeted therapies for children with refractory ACH. This case serves as a reminder of the importance of considering underlying systemic diseases when treating dermatologic conditions in pediatric populations, particularly when initial therapies fail to yield improvement. This presentation contributes to the growing recognition that autoimmune diseases may appear atypically in childhood and emphasizes the importance of long-term follow-up and flexible diagnostic frameworks in cases of refractory dermatologic conditions.

References

- Naik HB, Cowen EW. Autoinflammatory pustular neutrophilic diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(3):405–425.

- Smith PS, Ly K, Thibodeaux Q, et al. Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau: clinical perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2019;9:65–72.

- Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Recalcitrant palmoplantar eruptions. In: Odom RB, Berger TG, James WD, eds. Andrew’s Disease of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. WB Saunders Elsevier; 1990:214–216.

- Wang Z, Xiang X, Chen Y, et al. Treating paediatric acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau with adalimumab: a case series. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(1):195–196.

- Sharp GC, Irvin WS, Tan EM, et al. Mixed connective tissue disease—an apparent distinct rheumatic disease syndrome associated with a specific antibody to an extractable nuclear antigen (ENA). Am J Med. 1972;52(2):148–159.

- Alves MR, Isenberg DA. “Mixed connective tissue disease”: a condition in search of an identity. Clin Exp Med. 2020;20(2):159–166.

- Tani C, Carli L, Vagnani S, et al. The diagnosis and classification of mixed connective tissue disease. J Autoimmun. 2014;48–49:46–49.

- Haustein UF. MCTD—mixed connective tissue disease. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3(2):97–104.

- Dima A, Jurcut C, Baicus C. The impact of anti-U1-RNP positivity: systemic lupus erythematosus versus mixed connective tissue disease. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38(7):1169–1178.

- Kubo S, Tanaka Y. Evolution of diagnostic criteria and new insights into clinical testing in mixed connective tissue disease; antisurvival motor neuron complex antibody as a novel marker of severity of the disease. Immunol Med. 2024;47(2):52–57.

- Ellman MH, Pachman L, Medof ME. Raynaud’s phenomenon and initially seronegative mixed connective tissue disease. J Rheumatol. 1981;8(4):632–634.

- Felix A, Osei L, Delion F, et al. Longitudinal follow-up of mixed connective tissue disease and overlapping autoimmune diseases of childhood onset in the Afro-descendent population of the French West Indies. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2024;22(1):13.

- Tsai YY, Yang YH, Yu HH, et al. Fifteen-year experience of pediatric-onset mixed connective tissue disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(1):53–58.

- Ashrafzadeh S, Fedeles F. What the rheumatologist needs to know about skin biopsy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2023;37(1):101838.

- Ton E, Kruise AA. How to perform and analyze biopsies in relation to connective tissue diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23(2):233–255.