J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(12):13–16

by Khaled El Hoshy, MD, FAAD; Mona R. E. Abdel-Halim, MD; Eman El-Nabarawy, MD; and Suzan Shalaby, MD

by Khaled El Hoshy, MD, FAAD; Mona R. E. Abdel-Halim, MD; Eman El-Nabarawy, MD; and Suzan Shalaby, MD

Drs. El Hoshy, Abdel-Halim, El-Nabarawy, and Shalaby are with the Dermatology Department at Cairo University in Cairo, Egypt.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this study.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

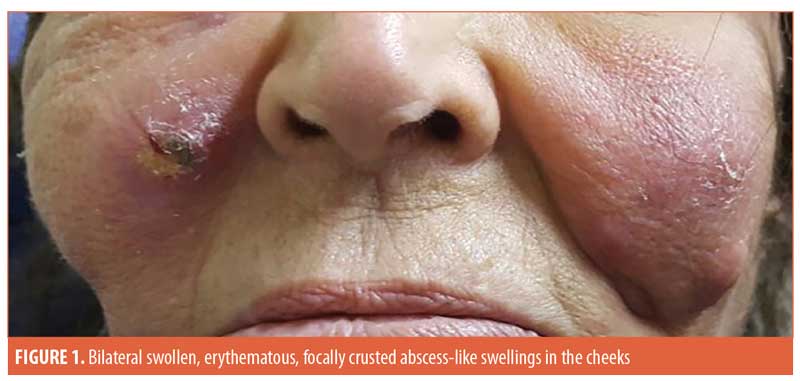

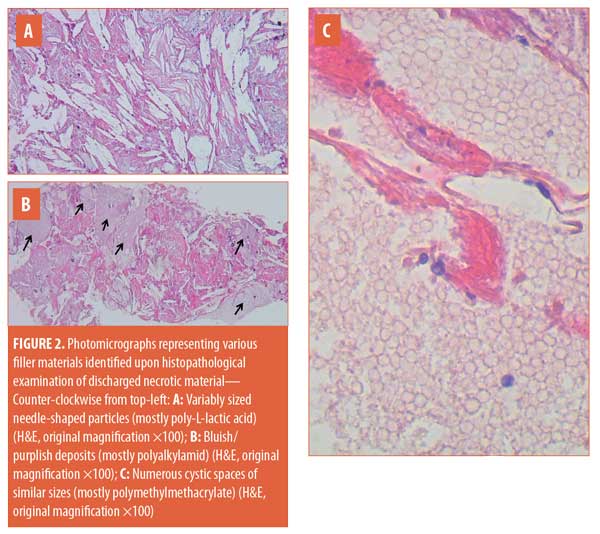

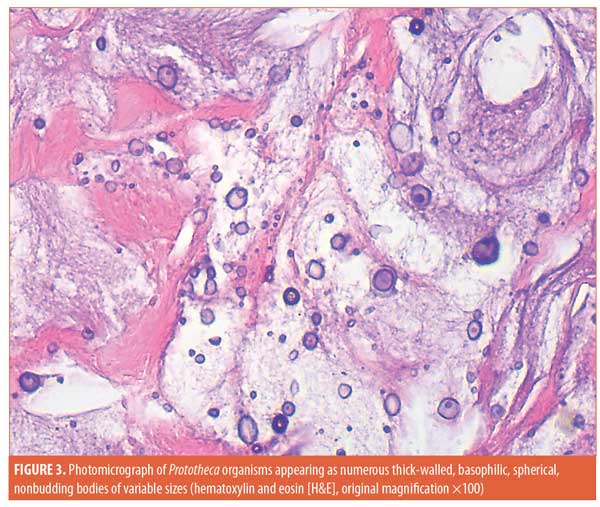

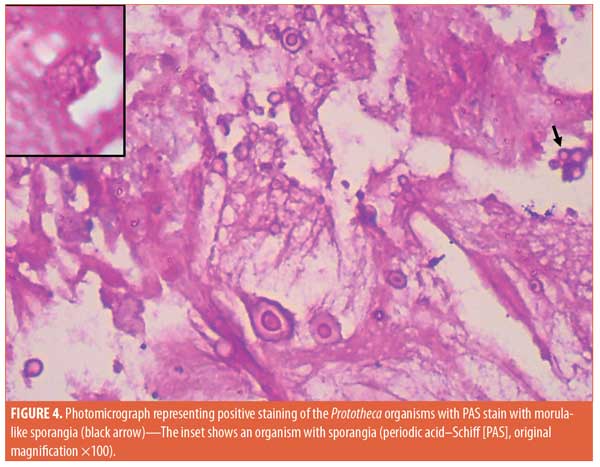

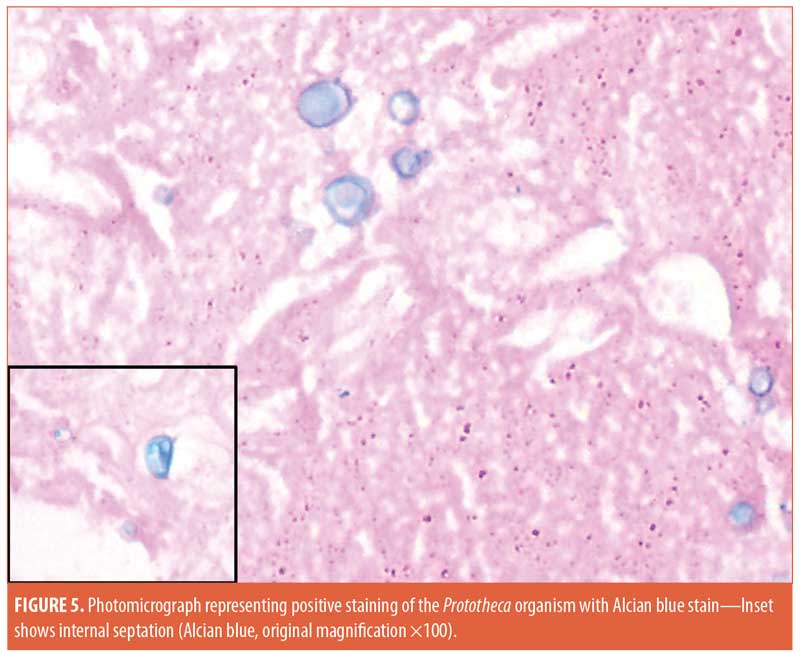

ABSTRACT: A 77-year-old female patient presented with bilateral tender, swollen, erythematous, focally crusted cheeks with a discharge of pus and necrotic material, which had developed one month after autologous fat transfer and a corrective injection procedure conducted to correct an overdone fat transfer. Histopathological examination of the discharged material using routine hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed degenerated collagen admixed with three different filler materials. Scattered all throughout the specimen were numerous thick-walled, basophilic, nonbudding spherical bodies of variable sizes. The bodies stained positively with Periodic acid–Schiff and Alcian blue and showed internal septation and sporangia with a morula-like appearance. The morphology of these bodies was characteristic of a Prototheca infection. The patient was treated by surgical drainage accompanied by itraconazole 200mg daily for six months, ultimately showing marked improvement.

KEYWORDS: Abscess, fillers, infection, Prototheca

In the currently advancing era of aesthetic dermatology, injectable dermal fillers are widely used as a surgical alternative for soft-tissue augmentation and the treatment of manifestations of aging skin. Furthermore, they are utilized in lip augmentation, increasing volume in the face, and managing atrophic scars. A variety of dermal filler types are available on the cosmetic market, including collagen-based products, hyaluronic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, poly-L-lactic acid, silicone, fat transfer, and polymethylmethacrylate.1

In most cases, dermal filler injection is a safe procedure with no significant side effects. However, even when performed by experienced individuals, dermal filler injections can be associated with significant side effects. These include early and late complications and can vary from minor events, such as swelling, tenderness, and bruising, to major complications, such as foreign body granulomatous reactions and infections.2

Infections complicating fillers can develop either early or late after the procedure. When infections complicate fillers, the injected area generally shows edema, erythema, warmth, and tenderness. Abscesses and sinuses discharging pus might develop. Patients might also experience fever. Early-onset infections are usually caused by simple pathogens, such as Staphylococus aureus, while those that are late-onset are often caused by less common pathogens.2 Mycobacteria have been found to be involved in late-onset infections after filler injections.3,4

In 2012, Shütz et al5 published a large case series of filler-induced infections. The infections manifested as facial cellulitis in three cases, periorbital abscess in four cases, and buccal space abscess in 15 cases. Examples of organisms involved included S. aureus, Klebsiela oxytoca, and anaerobic Gram-positive cocci. The duration between the time of injection and the onset of infection in these cases varied from one week to six years. While the early-onset infections were attributed mostly to a lack of antiseptic precautions—they developed predominantly among patients injected by beauticians in cosmetic salons—late-onset infections were noticed in this series typically in patients using semipermanent or permanent materials.

Moreover, the trauma of injection can lead to the exacerbation of other infections that might already be present in or close to the treated area, such as herpes simplex virus, human papilloma virus, molluscum, demodicosis, or yeast infections such as extensive pityrosporum folliculitis.6 Fungal infections can also complicate dermal filler injections.7 To the best of our knowledge, infections by Prototheca (an unpigmented eukaryotic algae) have not previously been reported following the injection of filler material. Here, we report an extraordinary case of a dermal filler injection complicated by protothecal infection.

Case Presentation

A 77-year-old female patient presented with bilateral tender, swollen, erythematous, focally crusted cheeks with a discharge of pus and necrotic material. The condition developed one month following autologous fat transfer and a corrective injection procedure conducted to correct an overdone fat transfer (Figure 1). The patient does not recall the exact name of the injected corrective material. Furthermore, 10 years earlier, she had received a session of dermal filler injection but did not recall any details of the injected material nor how many types of fillers were injected. No side effects developed at the time following this old injection.

Histopathological examination of the material discharged from the abscess using routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed degenerated collagen admixed with three different filler materials—specifically, variably sized needle-shaped particles (mostly poly-L-lactic acid) (Figure 2a); bluish/purplish deposits that were suspected to be hyaluronic acid but which stained negatively with Alcian blue, raising the possibility of polyalkylamid (Figure 2b); and numerous cystic spaces of similar sizes (mostly polymethylmethacrylate) (Figure 2c). Scattered all throughout the examined specimen were numerous thick-walled, basophilic, nonbudding spherical bodies of different sizes (Figure 3). These bodies stained positively with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and Alcian blue (Figures 4 and 5). Internal septation and sporangia with a morula-like appearance were detected. The morphology of these bodies was characteristic of a Prototheca infection. Unfortunately, culture was not feasible. Based on morphological characteristics, the patient was treated by surgical drainage accompanied by itraconazole 200mg daily for six months, ultimately achieving marked improvement (Figure 6).

Discussion

Two forms of the genus Prototheca can affect humans: Prototheca wickerhamii and Prototheca zopfii.8 Infection usually follows traumatic inoculation and results in localized cutaneous infections or olecranon bursitis in immunocompetent individuals. Immunocompromized patients usually suffer from disseminated systemic infections, including catheter infection and bacteraemia.9,10

In nature, algae tend to form complex communities with other microorganisms such as bacteria, protozoa, and fungi. These communities are known as biofilms. They are encapsulated within a self-produced matrix substance and become irreversibly stuck to any inert or living surface, both underwater and on land.11 Interestingly, the Prototheca species can produce a single-species biofilm on its own.12 Protothecosis is usually a chronic infection, and it has been speculated that the biofilm-producing ability of Prototheca can play a role in related infections because these organisms reduce the immune response and induce antimicrobial tolerance. Kwiecinski in 201512 found that the strongest biofilm of Prototheca was produced by Prototheca wickerhamii isolated from an infection, while the weakest biofilm was produced by an environmental isolate.

Biofilms can involve solid surgical implants, prostheses, catheters, stents, or any other form of foreign material including filler materials and, accordingly, are gaining more attention from dermatologists and dermatosurgeons since they might play a role in filler-related infectious side effects. When the body becomes compromised by bacteremia, a contaminated procedure, or trauma, a chronic biofilm becomes activated and induces an acute purulent infection. Even if the acute purulent infection is controlled by antibiotics, the underlying biofilm still persists and generates recurrences.13 This concept can explain the increased risk of infectious side effects related to repeated injections of fillers in the same region.

Two theories can explain the origin of Prototheca in our case. First, the fillers injected long ago could have been compromised by a Prototheca biofilm. They might have been dormant in the tissues for a time but became activated with the trauma of the more recent autologous fat transfer and the subsequent corrective injection, with a resultant acute infection. The second theory is that the infection was acquired during the recent procedure of fat transfer and the subsequent corrective injection through the use of contaminated syringes or contaminated injected material.

To the best of our knowledge, no similar cases of filler-induced cutaneous protothecosis have been reported. Most of the cases reported in the literature occurred in immunocompromised individuals.14,15 The most common clinical presentation mentioned is erythematous plaques studded with ulcers16 or pustules.17 Umblicated papules constitute another presentation.18 Histopathologically, the diagnosis is established by identifying the characteristic spherical bodies with morula-like sporangia amidst pan-dermal inflammation that can be either granulomatous or suppurative.

The treatment of localized cutaneous protothecosis involves the use of azoles, such as ketoconazole, itraconazole, fluconazole, or voriconazole.19 The combination of local heat therapy and azoles was also reported.20 Surgical excision of localized lesions alone or in combination with antifungals can also be efficient.21 Our patient responded well to the combination of surgical drainage and itraconazole. In conclusion, good awareness of protothecal infection as a cause of abscess-like swellings following dermal filler injection is important to have to facilitate the introduction of appropriate azole therapy and to avoid morbidity.

References

- Dayan SH, Bassichis BA. Facial dermal fillers: selection of appropriate products and techniques. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28(3):

335–347. - Gladstone HB, Cohen JL. Adverse effects when injecting facial fillers. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26(1):34–39.

- Rousso JJ, Pitman MJ. Enterococcus faecalis complicating dermal filler injection: a case of virulent facial abscesses. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(10):1638–1641.

- Cohen JL. Understanding, avoiding, and managing dermal filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34 (Suppl 1):S92–S99.

- Schütz P, Ibrahim HH, Hussain SS, et al. Infected facial tissue fillers: case series and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(10):2403–2412

- Lafaille P, Benedetto A. Fillers: contraindications, side effects and precautions. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(1):16–19.

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295–316.

- Huerre M, Ravisse P, Solomon H, et al. Human protothecosis and environment. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1993;86(5 Pt 2):484–488.

- Leimann BC, Monteiro PC, Lazéra M, et al. Protothecosis. Med Mycol. 2004;42(2):

95–106. - Lass-Flörl C, Mayr A. Human protothecosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(2):230–242.

- Patel P, Callow ME, Joint I, Callow JA. Specificity in the settlement modifying response of bacterial biofilms towards zoospores of the marine alga Enteromorpha. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5(5):338–349.

- Kwiecinski J. Biofilm formation by pathogenic Prototheca algae. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2015;61(6):511–517.

- Monheit GD, Rohrich RJ. The nature of long-term fillers and the risk of complications. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(Suppl 2):1598–1604.

- Wang F, Feng P, Lin Y, et al. Human cutaneous protothecosis: a case report and review of cases from Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Mycopathologia. 2018;183(5):821–828.

- Jenkinson H, Thelin L, McAndrew R, et al. Cutaneous protothecosis in a patient on ustekinumab for psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(10):1246–1248.

- Tseng HC, Chen CB, Ho JC, et al. Clinicopathological features and course of cutaneous protothecosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(9):1575–1583.

- Tan M, Pan JY, Chia HY, Oon HH. Cutaneous protothecosis on the bilateral wrists of a food handler. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42(1):

72–74. - Woo JY, Suhng EA, Byun JY, et al. A case of cutaneous protothecosis in an immunocompetent patient. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(2):273–274.

- Dalmau J, Pimentel CL, Alegre M, et al. Treatment of protothecosis with voriconazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 Suppl):

S122–S123. - Yamada N, Yoshida Y, Ohsawa T, et al. A case of cutaneous protothecosis successfully treated with local thermal therapy as an adjunct to itraconazole therapy in an immunocompromised host. Med Mycol. 2010;48(4):643–646.

- Kantrow SM, Boyd AS. Protothecosis. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21(2):249–255.