J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2025;18(6):10–13.

by Annika M. Hansen, MA; Rachel Seifert, BA; Abram Beshay, MD; Zachary Hopkins, MD; and Aaron Secrest, MD, PhD, MBA

Mses. Hansen, Seifert and Drs. Hopkins and Secrest are with the University of Utah School of Medicine in Salt Lake City, Utah. Dr. Beshay is with Kaiser Permanente in Woodland Hills, California. Dr. Secrest is also with the Department of Dermatology at Te Whatu Ora (Health New Zealand) in Christchurch, New Zealand.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Background: Both primary and secondary psychodermatoses are prevalent and dermatologists can play a pivotal role in their management. We sought to understand dermatologists’ training, comfort, and concerns for prescribing psychotropic medication for these conditions. Methods: We surveyed 49 dermatologists at the University of Utah, querying demographic variables, training environment, exposure to psychotropic medication use in training, current prescribing comfort, and current prescribing patterns. Associations between questionnaire responses and dermatologist demographics and training patterns were evaluated using ordinal logistic regression. Results: Across the 42 collected surveys, most had limited exposure to psychotropic medication and psychodermatoses management in residency, most were encouraged to refer these patients to psychiatry, and lack of training on use and side effects were the most commonly cited reasons for not prescribing psychotropic medications. Having more faculty who advocated for psychotropic medication use and training during residency on psychodermatoses were associated with greater prescribing comfort (OR=6.77, 1.54-29.8 and OR=6.09, 1.80–20.6 respectively). Conclusion: Most dermatologists surveyed had limited exposure and training using psychotropic medications for psychodermatoses. Lack of training and experience with these medications was a significant factor affecting prescribing comfort, highlighting the importance of expanded residency training on the use of psychotropic medications and the management of primary and secondary dermatoses. Keywords: Psychodermatoses, psychodermatology, psychiatric comorbidities, dermatology, medical dermatology

Introduction

Dermatologists frequently encounter patients with both dermatologic and psychiatric needs, with over 30 percent of dermatology patients estimated to have psychiatric comorbidities.1,2 Primary psychodermatoses are primarily seen by dermatologists. The field of psychodermatology seeks to address both the dermatologic and psychiatric needs of patients. Patients with psychocutaneous disorders often resist referrals to psychiatrists.3 Consequently dermatologists are often the sole providers with the opportunity to provide psychiatric care, at least initially. Despite the increasingly established prevalence of psychodermatoses, there remains a lack of psychodermatologic training and general discomfort using psychotropic medications among dermatologists.4 The survey aimed to better understand dermatologists’ training, comfort, and concerns for prescribing psychotropic medications at a large academic tertiary care center.

Methods

We designed a survey to assess dermatologist training, beliefs, and practices surrounding psychotropic medications. This was piloted in a departmental grand rounds and revised accordingly (Supplemental Survey). The finalized survey was sent via email to members of the University of Utah Department of Dermatology (49 dermatologists at time of survey, including residents). Two follow-up emails were sent in cases of non-response. Demographics and survey answers were summarized descriptively using mean/standard deviation (continuous variables) and counts/frequencies (categorical variables). Associations with comfort of prescribing psychotropic medications for primary psychodermatoses and secondary psychiatric comorbidities of dermatoses and participant demographics and training background were assessed using ordinal logistic regression. P-value <0.05 was considered significant and all tests were performed in Stata 17.1 (StatCorp, Texas).

Results

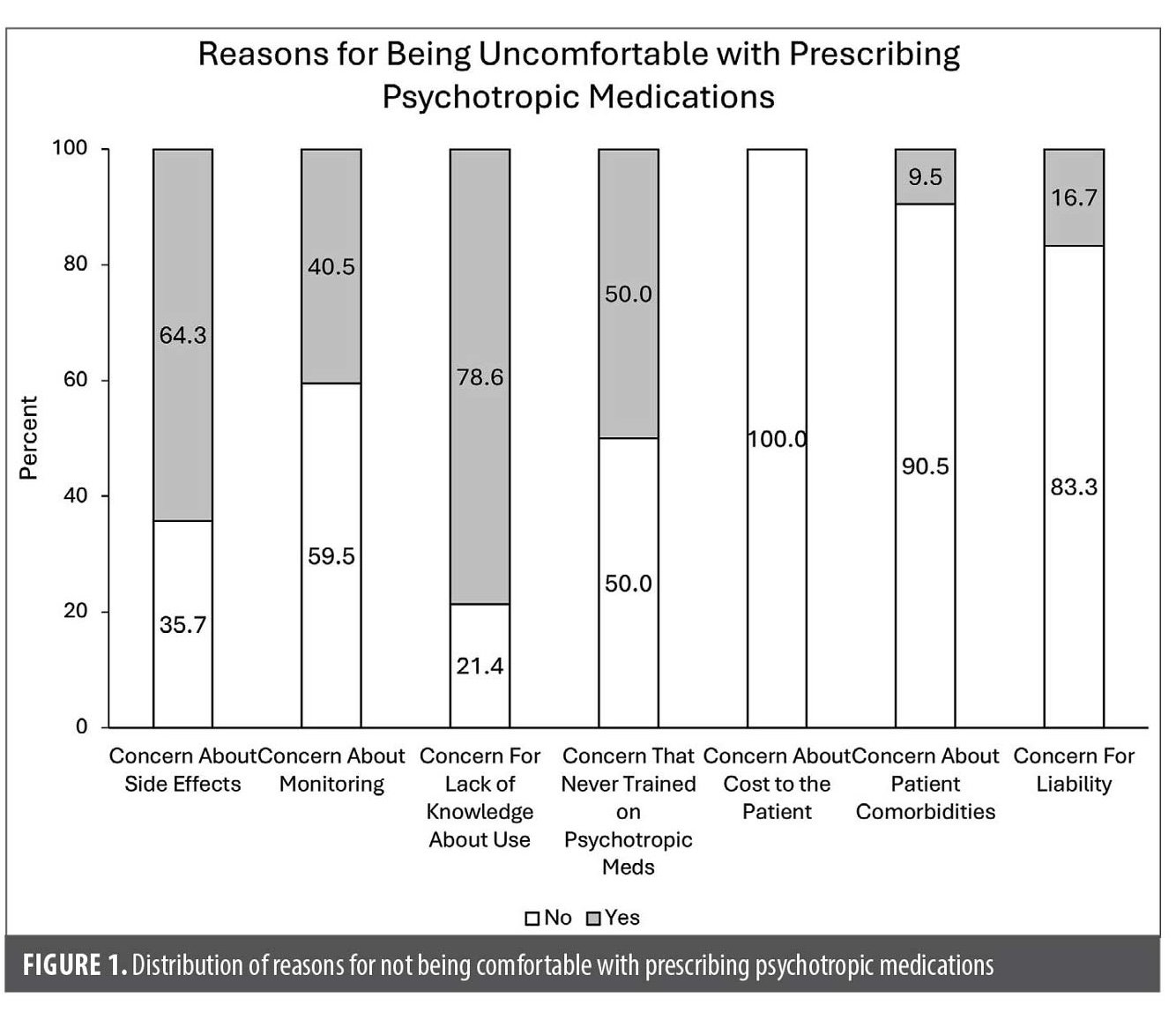

Forty-two of 49 dermatologists (31 attending dermatologists, 11 residents) completed the survey (86% response rate). Demographic details are provided in Table 1. Regarding training (Table 2), 54.8 percent went to programs where 1 to 2 faculty members advocated for the use of psychotropic medications, 7.1 percent attended programs where most of the faculty advocated for the use of these medications, and 19.0 percent had no faculty advocates. Regarding training on psychotropic use, 21.4 percent received instruction on dosing antidepressants and antipsychotics, while 61.9 percent had no training. Only 2.4 percent attended residencies with clinics specifically dedicated to psychodermatoses. Most respondents (83.3%) were encouraged to refer patients with psychodermatoses to psychiatry. The most common prescribing concerns included lack of knowledge about use (78.6%), side effects (64.3%), insufficient training (50.0%), and the need for monitoring (40.5%) (Figure 1).

Regarding prescribing comfort, about 30 percent of clinicians noted either “agree” or “strongly agree” that they are comfortable prescribing antipsychotics or anti-depressants for use in primary dermatoses (Table 3). However, 16.7 percent voiced comfort for secondary psychodermatoses. The most commonly treated primary psychodermatosis was delusions of parasitosis (57.1% of respondents) whereas depression was the most commonly treated secondary condition (31% of respondents) (Table 4). Associations between comfort prescribing psychotropic medications for primary psychodermatoses, included having at least one or two faculty who advocated for psychotropic medication use (OR=6.77, 95% CI 1.54–29.8), having received psychotropic medication training (OR=6.09, 1.80–20.6), and having encouragement to use psychotropic for primary psychodermatoses in residency (OR=1.25, 0.66–1.83). Associations with increased comfort prescribing psychotropic medications for secondary psychiatric comorbidities of skin disease included use of psychotropic medications being encouraged for secondary comorbidities in residency (OR=1.96, 1.17–3.28). We found no associations between other demographic and training factors.

Discussion

This survey has limitations. All responses were from a single, large, academic tertiary care center, therefore the results may not be generalizable. Despite this, our faculty trained in diverse locations and have diverse practice styles. Overall, we found that most dermatologists surveyed believe that psychotropic medications could be effective, but few noted having specific training prescribing these or having high levels of comfort prescribing these for primary dermatoses or secondary comorbidities. These data highlight the importance of encouraging this training during residency and of continued medical education on this topic (89.7% of participants voiced that a continuing medication course on this topic would be helpful).

Conclusion

Dermatologist trainee exposure to psychodermatology and psychotropic medication prescribing is critical for improving the care of patients suffering from primary and secondary psychodermatoses. Dermatologists are frequently frontline providers for both primary and secondary psychodermatoses and these data underscore the need for expanded resident education and specialty dermatology services targeting this population.

References

- Picardi A, Abeni D, Melchi CF, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in dermatological outpatients: an issue to be recognized. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(5):983–991.

- Raikhy S, Gautam S, Kanodia S. Pattern and prevalence of psychiatric disorders among patients attending dermatology OPD. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;29:85–88.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG, Holland PJ. Review of epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of common primary psychiatric causes of cutaneous disease. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29(4):418–427.

- Jafferany M, Vander Stoep A, Dumitrescu A, et al. The knowledge, awareness, and practice patterns of dermatologists toward psychocutaneous disorders: results of a survey study: psychodermatology and dermatologists. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(7):784–789.