J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(10):22–30.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(10):22–30.

by Mireille MD van der Linden, MD; Bernd WM Arents; and Esther J. van Zuuren, MD

Dr. van der Linden is with the Department of Dermatology at Amsterdam University Medical Center in Amsterdam, Netherlands. Mr. Arents is with Skin Netherlands in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands. Dr. van Zuuren is with the Department of Dermatology at Leiden University Medical Center in Leiden, Netherlands.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Morbihan’s disease (MD), also known as solid persistent facial edema, solid facial lymphedema or rosacea lymphedema, is a rare condition.

Objective. Despite existing case reports and literature reviews, clinical guidance for diagnosis and management is lacking. This review aims to provide comprehensive information on the etiology, differential diagnoses, diagnostics, and management of MD.

Methods. PubMed was searched up to April 2023 for relevant studies on MD with no language restriction. Furthermore, references were checked of found reports.

Results. A comprehensive overview of the literature and clinical guidance for MD. We found 95 studies involving 166 patients (118 male, 46 female and 2 gender unreported) evaluating management options, categorized into: isotretinoin (16 studies), isotretinoin plus antihistamines (8), isotretinoin plus corticosteroids (8), antibiotics (13), antibiotics plus corticosteroids (7), surgical debulking (10) and miscellaneous/combination treatments (43). Some studies contributed to two categories. Treatment with isotretinoin as monotherapy or combined with antihistamines, doxycycline or minocycline as well as surgical procedures demonstrated mostly satisfactory results, although recurrences were common. Longer treatment duration, of at least 6 to 12 months, is recommended for pharmacological treatments. Adding systemic or intralesional corticosteroids to previous treatments may be beneficial. Manual lymph drainage seems to contribute to satisfying result.

Limitations. This is not a systematic review and randomized controlled trials are lacking.

Conclusion. Diagnosis of MD is based on specific clinical features and excluding diseases with similar appearance. Prolonged treatment is often necessary to obtain satisfactory results, which might be limited to a partial and/or temporary response.

Keywords. Morbihan, solid facial lymphedema, solid persistent facial edema

Morbihan’s disease, also known as solid persistent facial edema, solid facial lymphedema or rosacea lymphedema, is a rare condition which may develop spontaneously without a tendency to resolve.1–4 First described by French dermatologist Robert Degos in 1957, Morbihan’s disease is named after the region in Bretagne where it was first observed.1–6 The disease causes disfigurement of the face and has therefore an enormous impact on patients’ quality of life, self-esteem and psychosocial well-being.3 Currently, there are no data on the incidence and prevalence, but it is considered a rare disease. Most cases have been described in White males and females of middle age, but the disease is also described in people with skin of color, as well as in younger and older individuals.1,5 Diagnosing and treating Morbihan’s disease can be challenging, and there are currently no clinical practice guidelines on its management. While several case reports and literature reviews have been published, there is a need for a comprehensive and practical review that can assist clinicians in diagnosing and managing patients presenting with this condition. This narrative review aims to provide an overview of Morbihan’s disease, including its clinical features, pathogenesis, differential diagnosis, and management options. It highlights the need for a personalized approach and treatment plans that consider the individual patient’s medical history, severity of symptoms, and response to therapy. By improving our understanding of this condition, we can provide better care to patients with Morbihan’s disease and alleviate their suffering.

Clinical Presentation

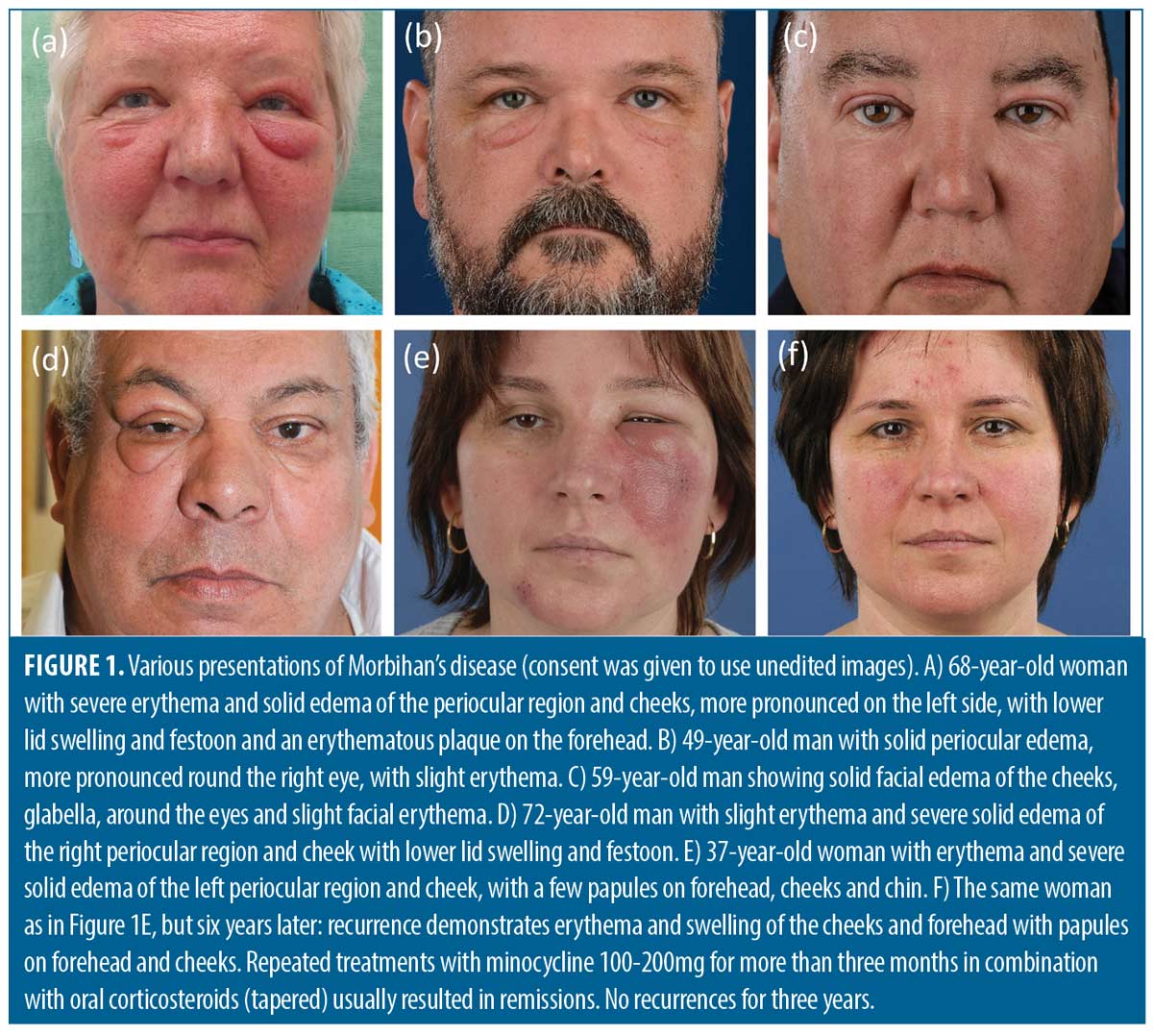

The clinical presentation of Morbihan’s disease is characterized by persistent erythema and firm non-pitting swelling involving the central and upper parts of the face. The swelling is typically symmetrical and bilaterally distributed (Figure 1)1,4,5,7 but can also be asymmetrical (Figures 1D and 1E), and may be accompanied by telangiectasias and papules. (Figure 1F).5 Patients may experience symptoms ranging from mild to very debilitating, with persistent erythema and swelling that can result in significant facial disfigurement. In particular festoons under the eyes and ptosis may occur, leading to narrowing of the visual field.1-5,7

It is important to note that the swelling itself is usually not painful or itchy. A history of rosacea is often supportive of the diagnosis of Morbihan’s disease as the condition is often regarded as a complication of rosacea, due to chronic inflammation and vasodilatation.1,4,5 However, it can also occur in the context of acne1,5,8–11 or as a distinct entity.2–4

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of Morbihan’s disease are not yet fully elucidated. The quintessential feature of the condition is persistent edema of the upper part of the face due to impaired lymphatic drainage, which can result from lymphatic obstruction and/or damage of blood and lymphatic vessels as a consequence of chronic inflammation.1,5 In several case studies, an increased number of mast cells has been reported and it is suggested that even if their amount is within normal range, mast cells’ cytokines may be involved in the pathogenesis of Morbihan’s disease.2,4,7

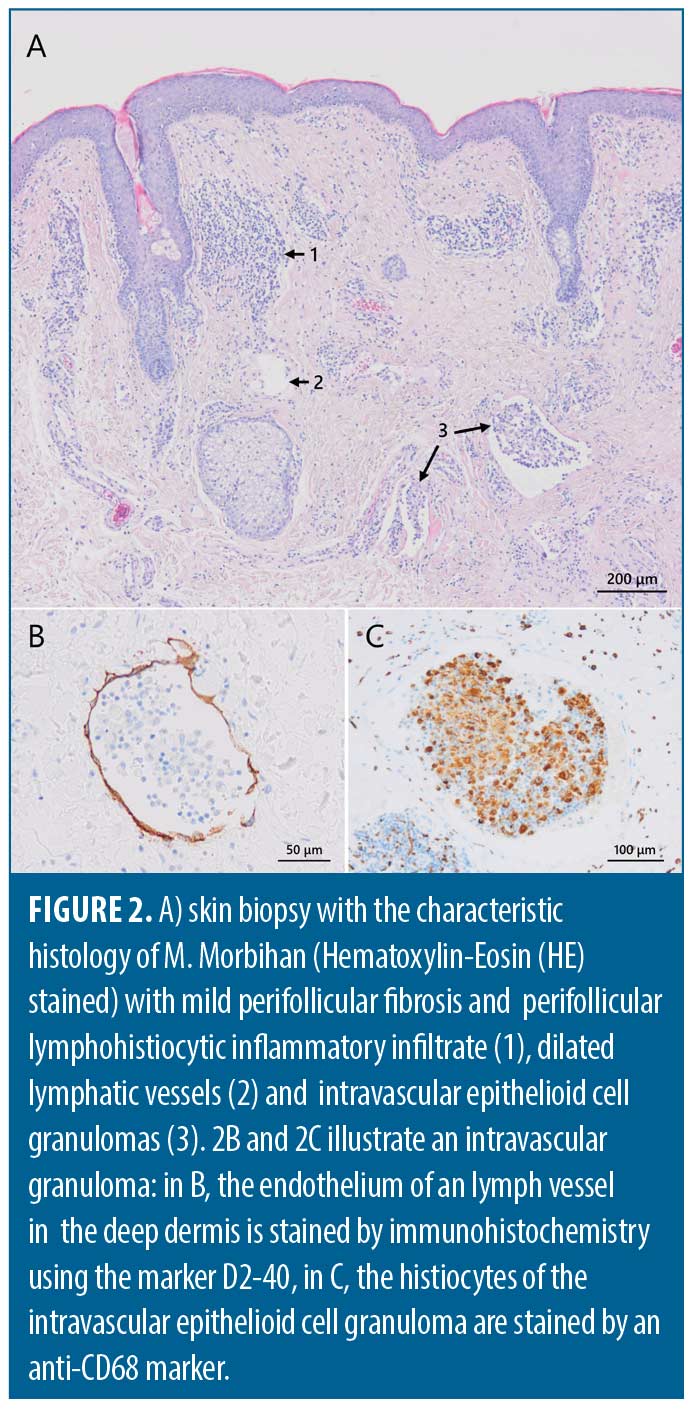

Histopathology of affected facial skin shows inflammatory features consistent with rosacea, including perivascular and periadnexal infiltrates of lymphocytes, histiocytes and sometimes neutrophiles.1,7 Most characteristic are dermal edema, dilated lymphatic vessels and the presence of clusters of mast cells (Figure 2).1,7 Although the histopathology is nonspecific, the diagnosis of Morbihan’s disease should be reconsidered in the absence of edema and dilated lymphatic vessels.7 Immunohistochemical staining with D2-40 and CD31 of histologic material is recommended to confirm the presence of lymphatic involvement. Demodex, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, mild perifollicular fibrosis, elastosis, clusters of mast cells and sometimes perilymphatic or intralymphatic epithelioid cell granulomas can also be found (Figure 2).2,6,7 The presence of epithelioid cell granulomas, which could be a possible cause of lymphatic obstruction and vessel wall damage, and clusters of mast cells, are indicative for the diagnosis.6,7 Absence of granulomas can be explained by either an early stage of the disease or by insufficient depth of the biopsy.6,7 Likewise, presence of epithelioid cell granulomas and increased number of mast cells might correlate with the stage of the condition.6 Biopsies are often taken after (unsuccessful) prior treatment, resulting in a less specific histopathology, further complicating the diagnosis.1

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on the characteristic clinical presentation while ruling out other diseases with similar appearances such as seen in thyroid disease, angioedema and Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome.3,4,12

To effectively exclude other diseases, a thorough clinical history is necessary, which should include inquiries about signs and symptoms of rosacea and any systemic complaints (Table 1). A complete physical examination is also essential, with particular attention given to inspecting the lips and tongue. Furthermore, histopathology of affected skin with specific staining, and laboratory tests are recommended. In some cases allergy tests, an X-thorax, or more advanced investigations such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), may be warranted (Table 1).4,12,13

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include a range of conditions such as Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (MRS), thyroid disease, angioedema, dermatomyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, chronic contact dermatitis, chronic actinic dermatitis, and neoplastic diseases (Table 1).3,4,12,13

Distinguishing between MRS and Morbihan’s disease can be challenging due to their shared clinical and histopathological similarities, including orofacial swelling, lymphatic vessel dilation, and non-caseating granulomas.7,13,14 While the complete triad of MRS includes orofacial granulomatosis, facial neuropathy, and a geographic tongue, the presentation may be incomplete. The first symptom of MRS is often orofacial swelling, especially in monosymptomatic cases, but may involve the mid and upper face, similar to Morbihan’s disease.13,15–18 Clinical history and careful physical examination can exclude MRS, as facial neuropathy and textural changes of the tongue (geographic tongue or lingua plicata), both indicative of MRS, are absent in Morbihan’s disease.

Serum thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) testing is indicated to exclude thyroid disease, which can also cause periorbital edema.1,5 Facial swelling can also be the result of an adverse drug reaction, due to e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and some non-benzodiazepine hypnotics.19–21 Unlike the swelling in Morbihan’s disease, this swelling is usually transient and resolves within 48 hours. Hereditary and non-hereditary angioedema can be ruled out by patient’s history and laboratory tests such as C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH), component 1q (C1q) and C4 complement.

Histopathology and laboratory tests, including antinuclear antibody (ANA) and creatine kinase (CK), can help exclude systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis.7

Sarcoidosis should be considered in case of systemic complaints and symptoms. Histology and laboratory testing of ACE and an X-thorax are recommended when sarcoidosis is suspected.

Allergological tests can exclude chronic contact dermatitis. Patch tests including open patch tests (fragrances and preservatives used in cosmetics) with additional readings after 30 minutes are advised, as both hidden immunologic contact urticaria and chronic contact dermatitis may contribute to impaired lymphatic drainage, and thus play a role in the persisting character or recurrence of Morbihan’s disease.12

History and histology might point at chronic actinic dermatitis. Presentation of asymmetric features can be suggestive of underlying neoplastic disease and more advanced investigations, e.g., computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are necessary to eliminate these underlying causes.4

Treatment

There are no registered and approved treatments for Morbihan’s disease. However, there are various treatment options that have been described in the literature, but the response is not always complete and recurrence can happen.1,5,22,23 Although we did not conduct a systematic literature search, we thoroughly searched PubMed and existing reviews for case reports or case series regarding treatment of Morbihan’s disease. Additionally, we meticulously screened the references of found articles for any additional relevant cases. The comprehensive search yielded a total of 95 studies encompassing 166 patients as outlined in Supporting information Table S1).1–9,11,13,14,18,22–103 Of the 166 patients, 118 were male, 46 were female and the gender of two patients was not reported. The mean age of the patients was 48.3 years with an age range of 14 to 88 years. Of the cases studied, 66 patients had a prior history of rosacea, 32 had a history of acne, one had extrafacial lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei and of the remainder (67/166) no pre-existing skin disease was reported. A variety of treatment options were described with varying rates of success. It should be noted that follow-up details were often lacking, but several studies did report that in the event of a recurrence, repeating the same treatment led to successful outcomes.

We categorized the reports per treatment modality: isotretinoin, isotretinoin combined with antihistamines, isotretinoin plus corticosteroids, antibiotics, antibiotics combined with corticosteroids, procedural treatments, and the remainder group featuring different combinations of treatments or differing treatment strategies among patients in case series (see Supporting information Table S1 on the online version of this article for details of the studies). In numerous reports, particularly those documenting results of surgical procedures, previous therapies often involving (alternative) anti-inflammatory drugs had failed.

View Supplemental Table 1 here:

van Zuuren Supplemental Table 1

Pharmacological treatment

Isotretinoin. A total of 16 studies involving 23 patients (15 male, 7 female and 1 unreported gender) described the effects of isotretinoin.3,4,7,22,24–35 Of the 23 patients, five had acne and five had rosacea. Good to complete response with isotretinoin therapy was established in 16 out of 23 patients,3,4,24,26–30,32,33,35 while a partial response was observed in two patients.25,30 The prescribed dosages ranged from 10 to 80mg isotretinoin per day with approximately 40mg isotretinoin being the most common. Figure 3 shows an example of a woman successfully treated with isotretinoin. A longer treatment duration (of at least 6–12 months) seems to be associated with more satisfying results. Prolonged treatment with isotretinoin does not always lead to a satisfactory outcome and can be associated with adverse events.5,22,31,34

Isotretinoin combined with antihistamines. In eight studies with 11 patients (8 male, 2 female and 1 unreported gender) the combination of isotretinoin with an antihistamine was investigated.11,36–42 All patients achieved a good to complete response. The daily dosage of isotretinoin ranged from 10mg per day to 0.7mg/kg per day. Ketotifen 1–2mg per day was the antihistamine of choice in six studies.36–41 Desloratadine 5mg per day was the preferred antihistamine in one study. Additionally, in one study the choice of antihistamine was not specified.11 Treatment duration varied from 3 to 16 months. Of note are the excellent results with low dose isotretinoin (10–20mg per day) with an antihistamine in 8 of the 11 patients.11,36,40–42 Low-dose and ultra-low-dose isotretinoin (10–20mg per day) are associated with mild side effects, which is a great advantage.27,33,42 Combination with ketotifen, an antihistamine and mast cell stabilizer, or desloratadine is recommended because of a possible synergistic effect based on anti-inflammatory properties of both isotretinoin and antihistamines.37,38,42,104

Isotretinoin combined with corticosteroids. The efficacy of a combination therapy consisting of isotretinoin and corticosteroids was investigated in eight studies involving eight patients, of which seven were male and one was female.1,11,43–47,93 Among them, six patients had acne (aged 18–38 years) and two had rosacea (both 61 years old). Prednisone was used in six cases at a daily dose of 20–40mg, deflazacort was used in one case at a daily dose of 30mg, and intralesional corticosteroids were used in one case (corticosteroid not specified). Treatment duration ranged from 2 to 8 months, with six patients showing good to excellent improvement.11,43–47 However, three studies reported recurrence of symptoms after the discontinuation of treatment.43,44,47 Cabral et al suggest that tapering of corticosteroids should be done gradually and slowly to prevent adverse effects.43 While corticosteroids are associated with well-known side effects, they can be considered as an adjunctive treatment option in some cases.

Antibiotics. Tetracyclines are well-known for their anti-inflammatory properties.105 Treatment response after minocycline and doxycycline may be correlated with the extent of mast-cell infiltration.2,50,52 However, mast cell infiltration is not observed in all cases of Morbihan’s disease.1,2,48 Thirteen studies comprising 20 patients (14 male and 6 female) evaluated the effects of predominantly tetracyclines.2,7,23,48–56,64 In 10 patients a history of rosacea was reported and in one acneiform eruptions in the perioral region. Seven of the eight patients treated with doxycycline 200mg per day for 30 days to 12 months showed marked improvement to complete response.7,48,51,52,64 In one study an initial dosage of 200mg doxycycline for two months, followed by doxycycline 40mg modified release for six months, proved to be successful.48 Similarly, four of the six patients treated with minocycline 100mg per day for four weeks to seven months demonstrated marked improvement.2,7,50,52 One patient switched after seven months from minocycline 100mg per day to doxycycline 200mg per day for another seven months because of side effects.52 It is important to take into account that minocycline can have rare but serious side effects such as drug induced lupus erythematosus, autoimmune hepatitis and hyperpigmentation (with prolonged use).106,107 Two patients only showed partial improvement after minocycline which might be due to a short treatment duration (1 and 2 months).53,56 Varying dosages of tetracycline were used in five patients with only one patient showing improvement,23,49,54 while one patient was treated with fleroxacin 100mg per day for two weeks and showed marked improvement in edema after several days.55

Antibiotics combined with corticosteroids. In seven studies comprising of eight patients (7 male and 1 female; 5 with rosacea and 3 with acne) antibiotics were combined with prednisone or prednisolone.6,57–62 The antibiotic regimens involved mainly doxycycline (200mg/day) or minocycline (100mg/day), whereas the dosages prednisone and prednisolone ranged from 10 to 60mg per day which was tapered over time. Overall, this combined treatment approach resulted in significant improvement in most cases, although mostly with recurrences after treatment cessation. Treatment duration was either not reported or relatively short (1 to 4 months) which may have contributed to the recurrences. Nevertheless, as stated before, recurrences are a common occurrence in Morbihan’s disease.

Procedural treatment. In cases where Morbihan’s disease persists despite pharmacological interventions and negatively impacts a patient’s quality of life or leads to visual impairment, surgical procedures, including blepharoplasty, lymphaticovenous anastomosis and debulking, may be considered.5,64,65,84,108 Authors of 10 studies including 27 patients (20 male and 7 female) have reported favorable outcomes of surgical debulking, however recurrences were frequently observed.5,7,14,63–68,75 Notably, successful outcomes of eyelid reduction surgery seem more likely in cases where histology shows no massive mast cell infiltration.85 Combining eyelid reduction surgery with intra-lesional corticosteroids may improve outcomes and provide more satisfactory results.5,63,64,75,85,94,96,100

Combination of pharmacological, procedural and/or adjunctive treatments.This is the most extensive group comprising of 43 studies including 93 patients (65 male and 28 female) highlighting the challenges faced by physicians in finding a definitive cure or effective treatment for Morbihan’s disease.1,5,7–9,11,13,18,70–103 While some studies have reported on single interventions, the majority have reported combinations of treatments or sequential treatments, each with their own dosage regimens and treatment durations. Certain studies support the results outlined in the preceding sections, while others demonstrate synergistic effects of combining treatments. Due to the limited number of cases and reliance on single case reports, drawing firm conclusions based on these findings is not possible. However, we will summarize two treatments. Manual lymphatic drainage was used in 20 patients (in 5 following debulking surgery) of which 16 showed improvement.73,76,79,80–82,85,87,89,96,100 A single case report described excellent results with the biologic omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody specifically binding to free human immunoglobulin E (IgE), administered for seven months.84 The authors hypothesized that omalizumab could potentially stabilize the mast cells and therefore could be beneficial in Morbihan’s disease. Further information on these combinations of pharmacological, procedural and/or adjunctive treatments can be found in Supporting information Table S1.

Based on the findings of our review we provide a comprehensive overview of diagnostics, potential differential diagnoses, and a list of recommended treatments (Tables 1–2).

Discussion

Having reviewed the literature on the diagnostics and treatments of Morbihan’s disease, combined with decades of clinical expertise and treating these patients, this disease however remains enigmatic. Is it even a distinct disease? Breaking it down to its essentials, Morbihan’s disease is a presentation of an imbalance in upper-face fluid build-up and draining of that fluid. This leads to a distinct pattern of solid and persistent upper-face edema. The reasons for fluid build-up can be multiple. In Morbihan’s disease, this is likely due to an inflammatory process. Likewise, the inadequate draining of fluid can have various underlying mechanisms, e.g. lymphatic dysfunction or other processes like physical tissue blockage due to infiltration or (smooth) muscle dysfunction. The key issue seems that the edema is not transient for misunderstood reasons.

The differential diagnoses of Morbihan’s disease and its treating strategies address the two issues mentioned. One aspect is reduction of fluid build-up: excluding and address other etiologies, reducing inflammation, and address capillary leakage, both pharmacologically. The other one is the inadequate lymph flow: excluding other (mechanical) etiologies, and use procedural interventions removing affected tissue. Since Morbihan’s disease is disfiguring the face, treatment is aimed at improving without causing harm. The latter implies resorting to procedural interventions only after pharmacological interventions have failed.

A striking finding of our review was that 71 percent of the patients were male, higher than anticipated. Surprisingly only about 40 percent had rosacea, which was lower than our initial expectations, while 19 percent suffered from acne, which was higher than we expected. It is uncertain whether selection bias or reporting bias contributed to these findings.

Effective management of Morbihan’s disease is essential, as the condition has the potential to considerably affect a patient’s quality of life and cause severe symptoms. Given the lack of spontaneous remission, prompt and accurate diagnosis, which involves recognizing the clinical features and ruling out alternative diagnoses, is imperative. An in-depth understanding of the available treatments and their outcomes can aid in making an informed decision for the most appropriate course of treatment.

This review provides an overview of the treatments described in the literature and their respective efficacy, which can facilitate optimal treatment selection.

Based on the literature reviewed, we have attempted to provide recommendations for the management of Morbihan’s disease in clinical practice. While many case reports and case series involved a search for the therapy that ultimately resulted in a satisfactory outcome, several studies have demonstrated that certain treatments yielded satisfactory outcomes in a majority of patients. These treatments include isotretinoin, preferably in combination with antihistamines, as well as doxycycline for at least six months and preferably longer. Systemic or intralesional corticosteroids may be considered in some instances. In cases with severe disfigurement or vision loss, surgical interventions have shown promising results. Additionally, manual lymphatic drainage can be combined with all treatments and has been reported to have a beneficial effect in the majority of cases.

Limitations. The limitations of this review include the lack of a thorough systematic review, as the authors were aware that mainly case reports were available on this rare disease, and well-designed clinical intervention studies were lacking. However, according to our knowledge this is the most complete review to date with the largest number of studies regarding management of Morbihan’s disease. Furthermore, we searched for publications without language restriction and checked references of found articles for additional literature. Another limitation is that this review is based on the included case reports and case series, which come with very low certainty of benefit of the discussed treatments. The summary of the recommended treatments is therefore based on the number of case reports and case series that reported treatment results, and expert opinion.

The strength of this review is that it presents a comprehensive overview of the available literature on Morbihan’s disease, the possible etiology, the most common differential diagnoses (and how to exclude them), a diversity in visual representations of the disease, and a list of treatments that may be most successful. Such an overview and guidance were lacking, and needed addressing. Since Morbihan’s disease is a rare condition, less experienced dermatologists might find this review helpful when dealing with a presentation of upper-facial edema. Furthermore, this review was co-authored with a patient advocate, as to bare and keep in mind the devastating consequences of having upper-facial edema and Morbihan’s disease, and that patients suffering from it need the best care and outcome possible, based on the evidence that is available.

Conclusion

Diagnosis of Morbihan’s disease should be based on recognizing the specific clinical features and excluding diseases with similar appearance. Prolonged pharmacological treatment is often necessary to obtain satisfactory results, which in some cases might be limited to a partial and/or temporarily response.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients with Morbihan’s disease for giving their informed consent to use their unedited images in this manuscript. Furthermore we are grateful for Marcus V. Starink, dermatologist, and Lies H. Jaspars, pathologist, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Amsterdam, for their valuable histological expertise and assistance with Figure 2.

References

- Boparai RS, Levin AM, Lelli GJ Jr. Morbihan Disease Treatment: Two Case Reports and a Systematic Literature Review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35(2):126–132.

- Fujimoto N, Mitsuru M, Tanaka T. Successful treatment of Morbihan disease with long-term minocycline and its association with mast cell infiltration. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(3):368–369.

- Heibel HD, Heibel MD, Cockerell CJ. Successful treatment of solid persistent facial edema with isotretinoin and compression therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6(8):755–757.

- Smith LA, Cohen DE. Successful Long-term Use of Oral Isotretinoin for the Management of Morbihan Disease: A Case Series Report and Review of the Literature. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(12):1395–1398.

- Yvon C, Mudhar HS, Fayers T, et al. Morbihan Syndrome, a UK Case Series. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36(5):438–443.

- Nagasaka T, Koyama T, Matsumura K, et al. Persistent lymphoedema in Morbihan disease: formation of perilymphatic epithelioid cell granulomas as a possible pathogenesis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33(6):764–777.

- Ramirez-Bellver JL, Pérez-González YC, Chen KR, et al. Clinicopathological and Immunohistochemical Study of 14 Cases of Morbihan Disease: An Insight Into Its Pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41(10):701–710.

- Connelly MG, Winkelmann RK. Solid facial edema as a complication of acne vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121(1):87–90.

- Kilinc I, Gençoglan G, Inanir I, et al. Solid facial edema of acne: failure of treatment with isotretinoin. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13(5):503–504.

- Jansen T, Grabbe S, Plewig G. Klinische Formen der Akne [Clinical variants of acne]. Hautarzt. 2005;56(11):1018–1026.

- Kuhn-Régnier S, Mangana J, Kerl K, et al. A Report of Two Cases of Solid Facial Edema in Acne. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7(1):167–174.

- Wohlrab J, Lueftl M, Marsch WC. Persistent erythema and edema of the midthird and upper aspect of the face (morbus morbihan): evidence of hidden immunologic contact urticaria and impaired lymphatic drainage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(4):595–602.

- Kuraitis D, Coscarart A, Williams L, et al. Morbihan disease: a case report and differentiation from Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26(6):13030/qt3gn1v677.

- Belousova IE, Kastnerova L, Khairutdinov VR, et al. Unilateral Periocular Intralymphatic Histiocytosis, Associated With Rosacea (Morbihan Disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2020;42(6):452–454.

- Belliveau MJ, Kratky V, Farmer J. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome presenting with isolated bilateral eyelid swelling: a clinicopathologic correlation. Can J Ophthalmol. 2011;46(3):286–287.

- Chen X, Jakobiec FA, Yadav P, et al. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome with isolated unilateral eyelid edema: an immunopathologic study. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(3):e70–77.

- Estacia CT, Gameiro Filho AR, da Silveira IBE, et al. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome: a rare variant of the monosymptomatic form. GMS Ophthalmol Cases. 2022;12:Doc04.

- Donthi D, Nenow J, Samia A, et al. Morbihan disease: A diagnostic dilemma: two cases with successful resolution. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211023655.

- Montinaro V, Cicardi M. ACE inhibitor-mediated angioedema. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;78:106081.

- Zammit G. Comparative tolerability of newer agents for insomnia. Drug Saf. 2009;32(9):735–748.

- Scheinfeld N, Bangalore S. Facial edema induced by isotretinoin use: a case and a review of the side effects of isotretinoin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5(5):467–468.

- Veraldi S, Persico MC, Francia C. Morbihan syndrome. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4(2):122–124.

- Vasconcelos RC, Eid NT, Eid RT, et al. Morbihan syndrome: a case report and literature review. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 Suppl 1):157–159.

- Balakirski G, Baron JM, Megahed M. Morbus Morbihan als Sonderform der Rosazea: Einblick in die Pathogenese und neue Therapieoptionen [Morbihan disease as a special form of rosacea: review of pathogenesis and new therapeutic options]. Hautarzt. 2013;64(12):884–886.

- Friedman SJ, Fox BJ, Albert HL. Solid facial edema as a complication of acne vulgaris: treatment with isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(2 Pt 1):286–289.

- García-Galaviz R, Domínguez-Cherit J, Toussaint-Caire S, et al. Solid persistent facial edema (Morbihan syndrome) in a young Mexican-Mestizo woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3S1):AB266.

- Gil F, Aranha J, Andrade I. Significant and Sustained Response with Short Cycle of Low-Dose Isotretinoin in Morbihan Disease. Skinmed. 2022;20(2):157–158.

- Harvey DT, Fenske NA, Glass LF. Rosaceous lymphedema: a rare variant of a common disorder. Cutis. 1998;61(6):321–324.

- Hu SW, Robinson M, Meehan SA, et al. Morbihan disease. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18(12):27.

- Humbert P, Delaporte E, Drobacheff C, et al. Oedème dur facial associé à l’acné vulgaire. Efficacité thérapeutique de l’isotrétinoïne [Solid facial edema associated with acne. Therapeutic efficacy of isotretinoin]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1990;117(8):527–532.

- Macca L, Li Pomi F, Motolese A, et al. Unilateral Morbihan syndrome. Dermatol Reports. 2021;14(2):9270.

- Manolache L, Benea V, Petrescu-Seceleanu D. A case of solid facial oedema successfully treated with isotretinoin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(8):965–966.

- Olvera-Cortés V, Pulido-Díaz N. Effective Treatment of Morbihan’s Disease with Long-term Isotretinoin: A Report of Three Cases. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(1):32–34.

- Singh PY, Baveja S, Vashisht D, et al. Morbihan disease: Look beyond facial lymphedema. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86(4):418–421.

- Veraldi S, Caputo R. Efficacia dell’isotretinoina sistemica in un paziente con edema solido facciale [Efficacy of systemic isotretinoin in a patient with solid facial oedema]. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2000;135(5):658–659.

- Dominiak M, Oszukowska M, Narbutt J, Lesiak A. Morbihan disease. Dermatol Rev/Przegl Dermatol. 2020;107(6):551–556.

- Jungfer B, Jansen T, Przybilla B, Plewig G. Solid persistent facial edema of acne: successful treatment with isotretinoin and ketotifen. Dermatology. 1993;187(1):34–37.

- Mazzatenta C, Giorgino G, Rubegni P, et al. Solid persistent facial oedema (Morbihan’s disease) following rosacea, successfully treated with isotretinoin and ketotifen. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(6):1020–1021.

- Pastuszka M, Kaszuba A, Kaszuba A. Solid facial oedema of acne: a case report. Post Dermatol Alergol. 2011;18(5):402–405.

- van Rappard DC, van der Linden MM, Faber WR. Een vrouw met peri-orbitale zwelling [A woman with periocular swelling]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156(17):A2845.

- Rebellato PR, Rezende CM, Battaglin ER, et al. Syndrome in question. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(6):909–911.

- Welsch K, Schaller M. Combination of ultra-low-dose isotretinoin and antihistamines in treating Morbihan disease – a new long-term approach with excellent results and a minimum of side effects. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32(8):941–944.

- Cabral F, Lubbe LC, Nóbrega MM, et al. Morbihan disease: a therapeutic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(6):847–850.

- Jerković Gulin S, Ljubojević Hadžavdić S. Morbihan Disease – An Old and Rare Entity Still Difficult to Treat. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2020;28(2):118–119.

- Lopéz S, Arellano M, Torres P. Morbihan syndrome: case presentation in a Mexican man. Abstract book 24th World Congress of Dermatology Milan 2019, 10-15 June. Available at https://www.wcd2019milan-dl.org/abstract-book/documents/abstracts/01-acne-rosacea-related-disorders/morbihan-syndrome-case-presentation-in-3600.pdf (accessed 6th of April 2023).

- Onder M, Bassoy B, Kevlekci C. Acne and lymphedema ‘‘Morbihan’s disease’’: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19 (Suppl 2):41.

- Ortiz Salvador JM, Subiabre Ferrer D, Ferrer Guillen B, et al. Morbihan disease: A case report with spontaneous resolution over time. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74 (Suppl 1):AB7.

- Chaidemenos G, Apalla Z, Sidiropoulos T. Morbihan disease: successful treatment with slow-releasing doxycycline monohydrate. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(2):e68–e69.

- Chen DM, Crosby DL. Periorbital edema as an initial presentation of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(2 Pt 2):346–348.

- Kabuto M, Fujimoto N, Honda S, et al. Successful treatment with long-term use of minocycline for Morbihan disease showing mast cell infiltration: A second case report. J Dermatol. 2015;42(8):827–828.

- Macellaro M, Gontijo LM, Vasconcellos RC, et al. Síndrome de Morbihan: relato de caso e revisão bibliográfica [Morbihan syndrome: case report and literature review]. Rev Med UFC. 2018;58(4):61–65.

- Okubo A, Takahashi K, Akasaka T, Amano H. Four cases of Morbihan disease successfully treated with doxycycline. J Dermatol. 2017;44(6):713–716.

- Rizzo A, Fiorani D, Lazzeri L, et al. Usefulness of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy in Morbihan syndrome. Skin Res Technol. 2021;27(5):974–976.

- Suzuki M, Watari T. Morbihan Syndrome. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(1):233.

- Uhara H, Kawachi S, Saida T. Solid facial edema in a patient with rosacea. J Dermatol. 2000;27(3):214–216.

- Utikal J, Poenitz N, Kurzen H, Goerdt S. Persistierendes Erythem und Odem des Gesichts [Persistent facial erythema and edema]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3(6):467–469.

- Camacho-Martinez F, Winkelmann RK. Solid facial edema as a manifestation of acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22(1):129–130.

- Lai TF, Leibovitch I, James C, et al. Rosacea lymphoedema of the eyelid. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2004;82(6):765–767.

- Mahajan PM. Solid facial edema as a complication of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 1998;61(4):215–216.

- Morales-Burgos A, Álvarez Del Manzano G, Sánchez JL, et al. Persistent eyelid swelling in a patient with rosacea. PR Health Sci J. 2009;28(1):80–82.

- Ranu H, Lee J, Hee TH. Therapeutic hotline: Successful treatment of Morbihan’s disease with oral prednisolone and doxycycline. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(6):682–685.

- Scerri L, Saihan EM. Persistent facial swelling in a patient with rosacea. Rosacea lymphedema. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131(9):1071,1074.

- Bernardini FP, Kersten RC, Khouri LM, et al. Chronic eyelid lymphedema and acne rosacea. Report of two cases. Ophthalmolog. 2000;107(12):2220–2223.

- Chalasani R, McNab A. Chronic lymphedema of the eyelid: case series. Orbit. 2010;29(4):222–226.

- Hattori Y, Hino H, Niu A. Surgical Lymphoedema Treatment of Morbihan Disease: A Case Report. Ann Plast Surg. 2021;86(5):547–550.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Alessi E. Elephantoid oedema of the eyelids. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18(4):459–462.

- Méndez-Fernández MA. Surgical treatment of solid facial edema: when everything else fails. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39(6):620–623.

- O’Donnell BF, Foulds IS. Visual impairment secondary to rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127(3):300–301.

- Aboutaam A, Hali F, Baline K, et al. Morbihan disease: treatment difficulties and diagnosis: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:226.

- Aksoy B, Üstün H, Çelik A, et al. Metronidazol ve Diüretik ile Tedavi Edilen Atipik Yerleşimli Morbus Morbihan Olgusu [A Morbus Morbihan Case With Atypical Presentation Treated By Use of Metronidazole and Diuretic]. Türk Dermatoloji Dergisi. 2009;3(4):89–92.

- Barragán-Estudillo ZF, Rivera-Gómez MI, López-Ibarra MM, Quintal-Ramírez MJ. Edema sólido facial persistente relacionado con acné (Morbihan) [Persistent facial solid edema related to acne (Morbihan)]. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2012;56(5):341–345.

- Bechara FG, Jansen T, Losch R, et al. Morbihan’s disease: treatment with CO2 laser blepharoplasty. J Dermatol. 2004;31:113–115.

- Borman P, Yaman A. Successful treatment for the different and rare cause of facial lymphedema: Morbus Morbihan disease. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:103–105.

- Bundino S. Su di un caso di malattia di Morbihan (edema eritematoso cronico faciale superior) [A case of Morbihan’s disease (superior facial chronic erythematous edema)]. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1991;126(10):511–514.

- Carruth BP, Meyer DR, Wladis EJ, et al. Extreme Eyelid Lymphedema Associated With Rosacea (Morbihan Disease): Case Series, Literature Review, and Therapeutic Considerations. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3 Suppl 1):S34–S38.

- Çinar GN, Özgül S, Nakip G, et al. Complex Decongestive Therapy in the Physical Therapist Management of Rosacea-Related Edema (Morbus Morbihan Syndrome): A Case Report With a New Approach. Phys Ther. 2021;101(9):pzab133.

- Dwyer C, Dick D. Facial oedema and acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127(2):188–199.

- Erbağci Z. Rosacea lymphoedema responding to prednisolone, metronidazole and ketotifen therapy in a patient with alopecia universalis. Gazi Medical Journal. 2000;11:47–49.

- Franco M, Hidalgo-Parra I, Bibiloni N, et al. Enfermedad de Morbihan [Morbihan’s disease]. Dermatol Argent. 2009;15(6):434–436.

- Helander I, Aho HJ. Solid facial edema as a complication of acne vulgaris: treatment with isotretinoin and clofazimine. Acta Derm Venereol. 1987;67(6):535–537.

- Hernández-Cano N, de Lucas-Laguna R, Lázaro-Cantalejo TE, et al. Edema sólido facial persistente asociado a acné vulgar: tratamiento con corticoides sistémicos [Persistent solid facial edema associated with acne vulgaris: treatment with systemic corticoids]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1999;90(4):187–190.

- Hölzle E, Jansen T, Plewig G. Morbus Morbihan–Chronisch persistierendes Erythem und Odem des Gesichts [Morbihan disease–chronic persistent erythema and edema of the face]. Hautarzt. 1995;46(11):796–798.

- Jay R, Rodger J. Resolution of rosacea-associated persistent facial edema with osteopathic manipulative treatment. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;28:83–86.

- Kafi P, Edén I, Swartling C. Morbihan Syndrome Successfully Treated with Omalizumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(7):677–678.

- Kim JE, Sim CY, Park AY, et al. Case Series of Morbihan Disease (Extreme Eyelid Oedema Associated with Rosacea): Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Ann Dermatol. 2019;31(2):196–200.

- Kou K, Chin K, Matsukura S, et al. Morbihan disease and extrafacial lupus miliaris disseminatus faceie: a case report. Ann Saudi Med. 2014;34(4):351–353.

- Kutlay S, Ozdemir EC, Pala Z, et al. Complete Decongestive Therapy Is an Option for the Treatment of Rosacea Lymphedema (Morbihan Disease): Two Cases. Phys Ther. 2019;99(4):406–410.

- Kwok C. Morbihan disease—challenges in diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(Suppl 1):AB53.

- Lamparter J, Kottler U, Cursiefen C, et al. Morbus Morbihan : Seltene Ursache ödematöser Lidschwellungen [Morbus Morbihan : A rare cause of edematous swelling of the eyelids]. Ophthalmologe. 2010;107(6):553–557.

- Laugier P, Gilardi S. L’Oedème érythémateux chronique facial supérieur (Degos). Ann Dermatol Venereol [Chronic erythematous oedema of the upper face (Degos). Morbihan disease].1981;108(6-7):507–563.

- Leigheb G, Boggio P, Gattoni M, et al. A case of Morbihan’s disease. Chronic upper facial erythemas oedema. Acta Derm Venerol. 1993;2(2):57–61.

- Messikh R, Try C, Bennani B, Humbert P. Efficacité des diurétiques dans la prise en charge thérapeutique de la maladie de Morbihan: trois cas [Efficacy of diuretics in the treatment of Morbihan’s disease: three cases]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012;139(8-9):559–563.

- Patel AB, Harting MS, Hsu S. Solid facial edema: treatment failure with oral isotretinoin monotherapy and combination oral isotretinoin and oral steroid therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14(1):14.

- Pflibsen LR, Howarth AL, Meza Rochin A, et al. A Navajo Patient with Morbihan’s Disease: Insight into Oculoplastic Treatment of a Rare Disease. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(9):e3090.

- Plange J, Rübben A, Merk HF, Megahed M. Morbus Morbihan. Eigene Entität oder Komplikation entzündlicher Gesichtsdermatosen? Hautarzt. 2006;57(5):447–448.

- Renieri G, Brochhausen C, Pfeiffer N, et al. Chronisches Lidödem assoziiert mit Rosazea (Morbus Morbihan): Differenzialdiagnostische Schwierigkeiten und Therapieoptionen [Chronic eyelid oedema and rosacea (Morbus Morbihan): diagnostic and therapeutic challenges]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2011;228(1):19–24.

- Torres-Gómez FJ, Neila-Iglesias J, Fernández-Machín P. Syndrome – Report of a Case and Literature Review. J Dermatolog Clin Res. 2018;6(1):1116.

- Tosti A, Guerra L, Bettoli V, Bonelli U. Solid facial edema as a complication of acne vulgaris in twins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17(5 Pt 1):843–844.

- Tsiogka A, Koller J. Efficacy of long-term intralesional triamcinolone in Morbihan’s disease and its possible association with mast cell infiltration. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31(4):e12609.

- Weeraman S, Birnie A. Rosacea causing unilateral Morbihan syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(10):e231074.

- Yu X, Qu T, Jin H, Fang K. Morbihan disease treated with Tripterygium wilfordii successfully. J Dermatol. 2018;45(5):e122–e123.

- Zhang L, Yan S, Pan L, Wu SF. Progressive disfiguring facial masses with pupillary axis obstruction from Morbihan syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(24):7163–7168.

- Zhou LF, Lu R. Successful treatment of Morbihan disease with total glucosides of paeony: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10(19):6688–6694.

- Reinholz M, Tietze JK, Kilian K, et al. Rosacea – S1 guideline. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11(8):768–780.

- Perret LJ, Tait CP. Non-antibiotic properties of tetracyclines and their clinical application in dermatology. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55(2):111–118.

- van Zuuren EJ. Rosacea. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1754–1764.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J, et al. Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(1):65–79.

- Kim JH. Treatment of Morbihan disease. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2021;22(3):131–134.