J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(6):48-52.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(6):48-52.

by Fatima Ishfaq, MD; Rohan Shah, BA; Shawana Sharif, MBBS, FCPS; Nadia Waqas, MBBS; Marielle Jamgochian, BA, MBS; and Babar Rao, MD;

Drs. Ishfaq and Sharif are with Benazir Bhutto Hospital at Rawalpindi Medical University in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Dr. Shah is with Rutgers Medical School in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Dr. Waqas is with Wah General Hospital in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Drs. Jamgochian and Rao are with Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Acne vulgaris is a common skin disease that frequently results in scarring. Scars secondary to acne can lead to physical disfigurements and a profound psychological impact. Early and effective treatment is the best means to minimize and prevent acne scarring. In patients with darker skin tones, current acne scar treatments pose complications, including dyspigmentation, further scarring, and overall unsatisfactory clinical outcomes.

Objective. We sought to compare the efficacy of microneedling versus 35% glycolic acid chemical peels for the treatment of acne scars.

Methods. Sixty patients with Fitzpatrick Skin Phototype IV to VI with atrophic acne scars were randomized into two groups: Group A underwent microneedling every two weeks for a total of 12 weeks and Group B received chemical peels every two weeks for a total of 12 weeks. Acne scar treatment efficacy was represented by an improvement greater than one grade from baseline according to the Goodman and Baron Scarring Grading System, measured two weeks after the completion of the last treatment session.

Results. Group A demonstrated more improved outcomes in acne scar treatment compared to Group B; 73.33% (n=22) of patients in Group A achieved treatment efficacy while 33.33% (n=10) in Group B did the same. Additionally, 26.67% (n=8) in Group A showed no efficacy after treatment compared to 66.67% (n=20) in Group B.

Conclusion: Microneedling provided better treatment outcomes compared to 35% glycolic acid peels for acne scar treatment in our patient population with Fitzpatrick Skin Phototypes IV to VI.

Keywords: Microneedling, chemical peel, acne, acne vulgaris, scar

Acne is estimated to affect 9.4 percent of the global population, making it the eighth most prevalent disease worldwide.1 Up to 85 percent of adolescents and young adults between the ages of 12 and 24 experience at least minor acne, which is also the most common skin condition in the United States, affecting nearly 50 million Americans annually.2,3 Aside from the inflammatory skin lesions, papules, pustules, and nodules characteristic of acne vulgaris, this chronic inflammatory skin condition can also result in textural changes within the superficial and deep dermis, leading to post-acne scars. These scars usually persist throughout life, often causing patients with acne to experience significant psychological distress such as embarrassment and anxiety. Approximately 12 to 14 percent of patients with acne scars also had psychological and social implications.4 Fortunately, the treatment of acne and acne scars has generated significant improvement in self-esteem and quality of life.5

The two main classifications of acne scars are atrophic and hypertrophic. Atrophic scars are flat, shallow depressions with diminished deposition of collagen. Hypertrophic scars are associated with excess collagen deposition and raised, firm lesions. Atrophic acne scars are more common than hypertrophic scars, with a ratio of 3 to 1, and are typically classified by their morphology as icepick, rolling, or boxcar scars.6 Icepick scars are narrow, deep, and sharply demarcated tracts extending into the deep dermis. Rolling scars are usually wider, shallower, and undulating. Finally, boxcar scars are wide and do not taper.7 Although morphologically distinct, these acne scar types are often seen together, making differentiation difficult. As such, multiple modalities exist for acne scar treatment depending on the patient’s scar characteristics.8 Some therapeutic options that have been described with variable clinical outcomes include microneedling, chemical peels, trichloroacetic acid (TCA) chemical reconstruction of skin scars (CROSS) technique, punch graft, punch excision, dermabrasion, ablative laser treatment, non-ablative laser treatment, autologous fat transfer, and dermal filler injections.

Microneedling is a relatively new, minimally invasive procedure that uses fine needles to puncture the epidermis. The microwounds stimulate growth factors and collagen production while the epidermis remains intact.9 Because it does not penetrate the deep dermis, microneedling is most effective for rolling or shallow boxcar scars.10 The Goodman and Baron Acne Scarring Grading System is a photographic assessment based on scar counts and severity, commonly used to evaluate treatment efficacy. The scale grades scars as macular (Grade 1), mild (Grade 2), moderate (Grade 3), and severe (Grade 4).11 When clinically assessing acne scar treatment options using the qualitative global scar grading system before and after treatment along with patient satisfaction scores, Saadawi et al12 demonstrated that microneedling was efficacious in 80 percent of patients as defined by a post-treatment reduction in scar grade.

Chemical peels are another option for treating acne scars. During a chemical peel, an ablative agent is applied to the surface of the skin to induce keratolysis or keratin coagulation. This results in controlled destruction of epidermal and dermal sections and subsequent exfoliation. Chemical peels are divided into three categories, depending on the depth of the wound created by the chemical agent. Superficial peels penetrate the epidermis only, medium-depth peels affect the entire epidermis and papillary dermis, and deep peels allow for controlled tissue injury at the mid-reticular dermis.13 This form of targeted inflammation activates new collagen and elastin deposition in the epidermis and dermis, improving the appearance of previously atrophic scars.14 Possible side effects of microneedling and glycolic acid chemical peels include erythema, edema, prolonged downtime, hyperpigmentation, and pain.12

In order to better understand which treatment options are better for atrophic acne scars, especially in patient populations with Fitzpatrick Skin Types (FST) IV to VI, our study compared the efficacy of microneedling and 35% glycolic acid peel for acne scar treatment. Specifically, glycolic acid peels were used in our study because it is the most popular, time-tested peeling agent and is an example of a superficial peel which penetrates only into the intraepidermal layers.13 Since previous literature comparing effectiveness between chemical peels and microneedling is limited, identifying which treatments have improved outcomes for acne scars will enhance the way we treat acne and its sequelae. Previous findings suggest that patients with FST IV to VI are more susceptible to complications after chemical peels, such as hyperpigmentation, due to a higher probability of developing an inflammatory response to a chemical irritant.15 Thus, aside from determining which treatment option is more efficacious for atrophic acne scars, since our patient population is predominantly of FST IV to VI, our study will also provide insight into whether either treatment is more beneficial, specifically for acne scar patients with darker skin tones.

Methods

In this six-month, randomized, controlled trial, 60 patients with acne scars presenting to Benazir Bhutto Hospital’s Department of Dermatology in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, were randomly divided into two groups: Group A received treatment with microneedling and Group B received treatment with 35% glycolic acid peels. The appropriate sample size was calculated using a WHO sample size calculator with five-percent level of significance and 80-percent power of study.

Patients between ages 15 and 50 of either sex, with clinically diagnosed scars resulting from inflammation within the dermis from acne of any size and duration, were included in the study. Conversely, patients with active acne assessed on clinical examination, history of collagen vascular disease or keloid formation, pregnant women, hypersensitivity to glycolic acid, bleeding disorders, HIV or HBV infection, or diabetes mellitus were excluded. All patients provided informed verbal consent and were consecutively sampled followed by random allocation into the two groups.

The patients were divided in half by picking slips containing the letter “A” or letter “B”. In Group A, 30 patients were treated with microneedling while in Group B, 30 patients received glycolic acid peeling. Each procedure was performed by one dermatologist with at least three years post-fellowship experience. Both groups received treatment every two weeks for six sessions. The microneedling group was provided with topical Vitamin A and C once a day for two weeks to enhance collagen formation with treatment. The microneedles were applied with minimal pressure and in various directions. A topical antibiotic was prescribed once a day for three days after treatment along with proper application of sunscreen. The glycolic acid chemical peel group cleansed the affected skin before the treatment to ensure equal penetration of the peel throughout the face. The patients washed their faces with soap and water before cleansing the skin to remove oils or cosmetics. For sensitive areas, such as around the lips and nose, we protected the patient with petroleum jelly. Like the microneedling group, this group was instructed to use moisturizing cream, topical antibiotic, and proper application of sunscreen daily following treatment for three days. All data, including age, sex, duration of acne scars, size of scars, type of scar, grade of scar (1, 2, 3, or 4), place of residence (rural/urban), occupation (employed/unemployed), and efficacy (yes/no) was collected by the dermatologist and stratified.

Acne scar treatment efficacy was represented by an improvement greater than one grade from baseline according to the Goodman and Baron Scarring Grading System, measured two weeks after the completion of the last treatment session. Efficacy was recorded as “yes” or “no”. Collected data was analyzed using SPSS Version 25.0. Mean and standard deviation were calculated for age, duration of acne scar, and size of scar, while frequency and percentage were calculated for sex, type of scar, grade of scar, place of living, occupation, and efficacy. Chi-squared tests were conducted to compare the efficacy of both groups and for all the stratified variables to determine their effect on treatment. All p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 60 cases (30 in Group A and 30 in Group B) fulfilling the selection criteria were evaluated to compare the efficacy of microneedling and 35% glycolic acid peels for acne scar treatment. The mean age in Group A (microneedling treatment) was 36.53 +/- 7.92 years with 63.33 percent of patients from 15 to 40 years of age. Comparatively, the mean age in Group B (glycolic acid peel) was 41.27 +/- 5.44 years with 36.67 percent of patients from 15 to 40 years of age (Table 2). Thirty percent of the participants in Group A were male, and 33 percent of participants in Group B were male (Table 3). The mean duration and size of the acne scars in Group A were 22.67 +/- 8.14 months and 2.87+/- 0.69 mm respectively. Similarly, the mean duration and size of acne scars in Group B were 19.7 +/- 7.86 months and 2.71+/- 0.91 mm, respectively.

The type of acne scar was also categorized based on morphology. In Group A, 50 percent had icepick scars, 23.33 percent had rolling scars, and 26.67 percent had boxcar scars while Group B had 33.33 percent icepick, 30 percent rolling, and 36.67 percent had boxcar scars. Of those with icepick acne scar morphology with positive treatment efficacy, 11/13 had received microneedling treatment. Similarly, of those with rolling type acne scars with positive treatment efficacy, 7/11 had received microneedling treatment. In both groups, those who did not display efficacious treatment were more likely to have received the glycolic acid chemical peel treatment. (Table 1)

After evaluating the acne scars post-treatment, we determined that 73.33 percent (n=22) in Group A and 33.33 percent (n=10) in Group B were treated effectively according to our efficacy criteria (p=0.001). Additionally, 26.67 percent (n=8) in Group A and 66.67 percent (n=20) in Group B showed no efficacy after treatment. (p=0.001) (Table 4).

Discussion

Acne scars are a common and undesirable outcome of acne vulgaris which accounts for about one-fifth of all visits to dermatologists in patients aged 13 to 35 years in Pakistan.16 In the South Asian population, acne prevalence among adolescents has been reported to be 91 percent in males and 79 percent in females. In a separate, epidemiological study evaluating the prevalence of acne in different populations, clinical acne was found in 30 percent of Asian women compared to 24 percent in Caucasian women. Additionally, all racial groups displayed equal prevalence between acne subtypes except for Asian women who were more prone to inflammatory acne than comedonal acne.17

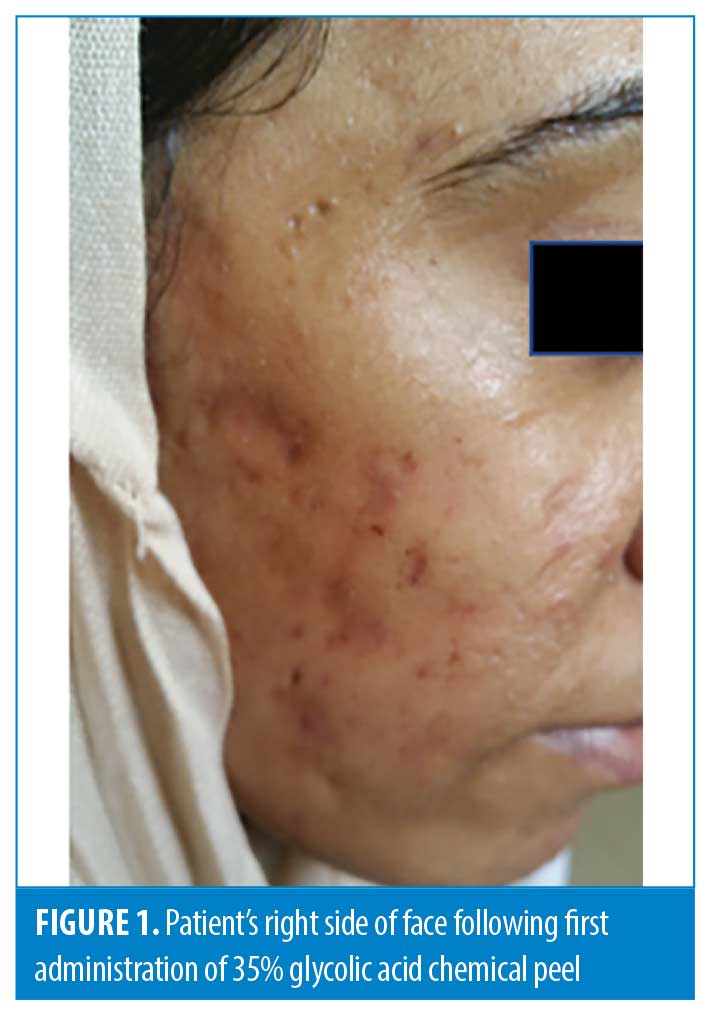

In our study, we compared the efficacy of microneedling and 35% glycolic acid peels in the treatment of acne scars and found microneedling therapy to be significantly more effective in lowering atrophic acne scar grade than 35% glycolic acid peels (Figures 1 and 2). These results validate previous research in the field regarding microneedling as a treatment option for atrophic acne scars while also suggesting that it may be a better option than chemical peels (Figures 3 and 4).

Our study’s population was predominantly FST IV, V, and VI. Cohen et al18 note that in darker skin, chemical peels can be associated with prolonged recovery and complication risk. These complications include dyspigmentation, further scarring, and overall unsatisfactory clinical outcomes. Microneedling may offer a more desirable safety profile in the skin-of-color population because it keeps the epidermis partially intact, and the retained skin barrier promotes recovery while limiting risk of infection. Aside from their comparison to chemical peels, microneedling might be a better option than other minimally invasive options, such fractional lasers, which are non-ablative but can thermally activate melanocytes leading to hyperpigmentation.18 Fabbrocini et al6 investigated the use of microneedling in acne and non-acne scars between patients with FST I to II, III to V, and VI. Notably, there was a significant improvement of acne scars in all groups with similar side effect profiles of erythema. Furthermore, there were no reports of hyperpigmentation in any of the groups up to one year following final treatment.6 These results not only parallel our study’s findings in which FST IV, V, and VI patients had better outcomes in acne scar treatment, but also suggest that microneedling may be the better option for acne scar treatment in patients with skin of color.

Although our study implies microneedling might serve as a better option than chemical peels for acne scar treatment, it remains unclear whether combined dual therapy can deliver improved outcomes. A systematic review evaluating 33 articles on microneedling techniques used for acne scarring demonstrated improvement of acne scar appearance after microneedling treatment. However, evidence was inconsistent when comparing microneedling therapy alone to dual therapy or to fractional laser treatment.19 Contrarily, another study compared the use of microneedling alone with a combination of 70% glycolic acid and microneedling and found that the combined treatment resulted in better scar improvement along with improved skin texture. This concurrent treatment was provided at fixed intervals of microneedling suggesting that dual therapy may be an option and further investigation into the optimal balance between chemical peels and microneedling is required.20 In a similar study, 60 patients were either treated with microneedling alone or microneedling with 35% glycolic acid peels. Mean improvement after three-month follow up was 31 percent in the group with microneedling alone and 62 percent in the combined treatment group.21 Interestingly, our study results showed a similar comparison between microneedling and chemical peels, suggesting that glycolic acid chemical peels could be useful in acne scar treatment when combined with an interval microneedling regimen.

One point to consider is that not all atrophic acne scars are considered equal in their responsiveness to treatment. In a systematic review by Gozali et al,22 different treatment options are suggested depending on lesion morphology. Chemical peels demonstrated a better overall response for icepick scars while microneedling was the better option for rolling scars. Both options were equally effective in treating boxcar scars.22 Our study’s results did not validate this and are more consistent with Saadawi et al’s results, as Group A had a greater proportion of patients presenting with icepick scars, yet still had better response to microneedling treatment. Our study also agrees with previous studies in that the response of rolling acne scars was better than that of boxcar acne scars for the microneedling group and overall, those with this scar morphology had better outcomes with improved efficacy.12 However, our study also demonstrates improved efficacy for icepick morphology scars within the microneedling group which, to our knowledge, has yet to be identified. This finding has the potential to broaden the use of microneedling treatment to those with icepick scars. Future studies should attempt to ensure acne scar morphology is the same in both treatment groups to validate Gozali et al’s findings.

Microneedling as a treatment option has gained recent recognition for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and safety.12 However, microneedling applications are not limited to acne scar treatment. Multiple studies indicate its efficacy and safety for melasma, photodamage, skin rejuvenation, hyperhidrosis, alopecia, and for facilitating transdermal drug delivery.23 Adverse effects of microneedling are rare and the most common reaction to microneedling includes a transient erythema and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Other reported rare side effects include tram-track scarring, milia, and pruritus.24

Limitations. This study included 60 patients and while an appropriate sample size was calculated with a five-percent level of significance and 80-percent statistical power, larger, longer, and more randomized controlled trials are needed to further validate these results. Although our patients were all FST IV to VI, we are unable to conclude definitively on the specific benefits of microneedling on darker skin tone, since there was no control group in this study with FST I to III. Also, our study compared two treatment groups, but it would have been ideal to also have a control group receiving no treatments to ensure improvements were due to the treatments and no other contributing factor. Finally, the p-value for Groups A and B when stratified for age was 0.36 and 0.28 respectively and when stratified for sex, the p-value was 0.59 and 0.27 respectively. Since sex and age may not be considered significantly similar between the groups, further studies with larger sample groups are needed.

Conclusion

Acne scars have been shown to have a significant psychological impact on patients, especially in adolescents. Thus, it is imperative to identify reliable, safe, and effective treatment options to mitigate morbidities in our population. There are various treatments including chemical peels and microneedling. Our study identifies microneedling as a better option than 35% glycolic acid chemical peels. This may significantly change the way clinicians practice and treat acne scars as a greater emphasis will be placed on microneedles, a growing and promising option. Based on our study’s findings, we envision either using microneedling as a first line option followed by chemical peels if limited improvement is witnessed, or using them in combination with one another. Finally, our study’s patients were of FST IV to VI, and thus, our results provide a foundation for acne scar treatments specifically in patients with darker skin tone. As a result, the positive outcomes seen with microneedling in this group might be useful for any clinician who regularly treats patients with darker skin tones. Further research on the parameters and combination availability of microneedling is needed to incorporate the treatment into everyday practice for acne scars however, our study shows preliminary but promising results.

References

- Tan JK, Bhate K. A global perspective on the epidemiology of acne. Br J Dermatol. 2015; 172: 3–12

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006; 55 (3): 490–500

- Bhate K, Williams HC. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013; 168 (3): 474–485

- Capitanio B, Sinagra V, Bordignon PC. Underestimated clinical features of postadolescent acne. J Americ Acad Dermatol. 2010; 63 (5): 782–788.

- Newton JN, Mallon E, Klassen A. The effectiveness of acne treatment: an assessment by patients of the outcome of therapy. Br.J Dermatol.1997; 137:563

- Fabbrocini G, Annunziata MC, D’Arco V, et al. Acne Scars: Pathogenesis, Classification and Treatment. Dermatology Research and Practice. 2010; e893080.

- Ibrahim ZA, El-Ashmawy AA, Shore OA. Therapeutic effect of microneedling and autologous platelet fish plasma in the treatment of atrophic scars: a randomized study. J Cosa et Dermatol. 2017; 3: 3–8.

- Connolly D, Vu HL, Mariwalla K, et al. Acne Scarring—Pathogenesis, Evaluation, and Treatment Options. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017; 10 (9): 12–23

- Singh A, Yadav S. Microneedling: advances and widening horizons. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016; 7(4):2414–2541

- El-Domyati M, Abdel-Wahab H, Hossam A. Microneedling combined with platelet-rich plasma or trichloroacetic acid peeling for management of acne scarring: a split-face clinical and histologic comparison. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018; 17(1): 73–83.

- Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring-a quantitative global scarring grading system. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006; 5(1): 48–52

- Saadawi AN, Esawy AM, Kandeel AH, et al. Microneedling by dermapen and glycolic acid peel for the treatment of acne scars: Comparative study. J Cosmet Dermatol 2019; 18(1): 107–114

- Soleymani T, Lanoue J, Rahman Z. A Practical Approach to Chemical Peels. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018; 11(8): 21–28

- O’Connor AA, Lowe PM, Shumack S, et al. Chemical peels: A review of current practice. Aust J. Dermatol. 2018; 59(3): 171–181

- Conceição K., Adriano A.R., Lima T.S. (2017) Chemical Peels for Dark Skin. In: Issa M., Tamura B. (eds) Chemical and Physical Procedures. Clinical Approaches and Procedures in Cosmetic Dermatology. Springer, Cham.

- Ali G, Mehtab K, Sheikh ZA, et al. Beliefs and perceptions of acne among a sample of students from Sindh Medical College, Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60(1):51–54.

- Perkins AC, Cheng CE, Hillebrand GG, et al. Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among Caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011; 25 (9): 1054–1060

- Cohen BE, Elbuluk N. Microneedling in skin of color: A review of uses and efficacy. Derm Surg 2015; 74 (2): 348–355.

- Mujahid N, Shareef F, Maymone MBC, et al. Microneedling as a Treatment for Acne Scarring: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Surg. 2020; 46 (1): 86–92.

- Rana S, Mendiratta V, Chander R. Efficacy of microneedling with 70% glycolic acid peel vs microneedling alone in treatment of atrophic acne scars—A randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017; 16 (4): 454–459

- Sharad J. Combination of microneedling and glycolic acid peels for the treatment of acne scars in dark skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011; 10 (4): 317–323

- Gozali MV, Zhou B. Effective Treatments of Atrophic Acne Scars. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015; 8(5): 33–40

- Iriarte C, Awosika O, Rengifo-Pardo M, et al. Review of applications of microneedling in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017; 10: 289–298

- Gowda A, Healey B, Ezaldein H, et al. A Systematic Review Examining the Potential Adverse Effects of Microneedling. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021 Jan;14(1):45–54.