J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(2):14–20.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(2):14–20.

by Azza Farag, MD; Mostafa Hammam, MD; Nada Alnaidany, MD; Eman Badr, mD; Mustafa Elshaib; Aliaa El-Swah, MS; and Wafaa Shehata, MD

Drs. Farag, Hammam, El-Swah, and Shehata are with the Dermatology, Andrology and Venereology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University in Al Minufya, Egypt. Dr. Alnaidany is with the Clinical Pharmacy Department, Faculty of Pharmacy, MSA University in 6th of October City, Egypt. Dr. Badr is with the Medical Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University in Al Minufya, Egypt. Dr. Shehata is with the Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University in Al Minufya, Egypt. Mr. Elshaib is a medical student at Menoufia University in Al Minufya, Egypt.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background: Melasma is a chronic hypermelanotic disorder that is challenging to treat; no single effective therapeutic agent for it has been discovered. Methimazole, an oral antithyroid drug, has a skin depigmenting effect when used topically.

Objective: We sought to evaluate the efficacy and safety of methimazole, applied during microneedling sessions and additional topical use in between sessions, for the treatment of melasma.

Methods: This split-face study included 30 Egyptian patients with melasma, each of whom received 12 microneedling sessions once per week for 12 weeks followed by topical methimazole on the right side of face and placebo on the left side. In between the sessions, topical methimazole 5% cream was applied twice per day on the right side and placebo on the left side. Assessments were performed using the Hemi-melasma Area and Severity Index (hemi-MASI) percentage of improvement, patient satisfaction, dermoscopy, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) serum levels.

Results: There were significant clinical and dermoscopic improvements; hemi-MASI scores on the methimazole-treated right sides were decreased (p<0.001). The percent of hemi-MASI score improvement was significantly associated with the malar pattern (p=0.031) and epidermal type (p=0.04) of melasma. About 70 percent of our studied patients reported being satisfied with their treatment response (7% excellent, 33% good, 30% fair). No significant local or systemic side effects were observed. Pre- and posttreatment serum TSH levels were within the normal range in all treated cases.

Conclusions: Methimazole has the potential to be a safe and promising therapeutic agent for the treatment of melasma via dermapen-delivered microneedling sessions with topical use in between sessions.

KEYWORDS: Methimazole, melasma, microneedling

Melasma is one of the most common acquired pigmented disorders that affects the sun-exposed areas of the skin. It is more common among women than men and in Black individuals than White individuals, with a prevalence rate of 1.5 to 33.3 percent.1 Increased sun exposure, pregnancy, and hormonal and genetic factors are considered the most important etiological factors; however, the actual cause and pathogenesis of melasma still have not been completely clarified.2

There are many modalities for the treatment of melasma, but currently, hydroquinone is the gold standard in melasma treatment.3 However, it has been reported that hydroquinone’s cytotoxic effect is not restricted to melanocytes, also possibly affecting keratinocytes as well. Additionally, in-vitro studies have demonstrated that hydroquinone has mutagenic effects on hamster ovarian cells and on Salmonella. These notes have led to the search for alternative depigmenting agents that are safer, even if not as effective.4

Methimazole (MMI) is an oral antithyroid medication used in the treatment of hyperthyroid states. Chemically, it is 1-methyl-2-mercaptoimidazole.5 The skin-lightening effect of MMI was discovered in 2002, where its topical application for six weeks was found to cause evident cutaneous depigmentation in guinea pigs. Tissue histologic examination from the studied animals revealed notably lowered melanin content in the epidermis and morphological changes in melanocytes.6 Additionally, it has been shown that MMI inhibits melanin synthesis with no melanocytotoxic effect in cultured melanocytes.7 Moreover, MMI was suggested as a treatment agent for melasma in few human trials at different populations, in which it was used as a topically prepared cream in all of these trials.2,8–10

The aim of this study was to investigate the possible depigmenting effect and safety of MMI in the treatment of melasma via dermapen-transported microneedling sessions plus topical (MMI 5% cream) use in between sessions in a sample of Egyptian patients with melasma.

Methods

Patients. This split-face study included 30 patients clinically diagnosed with melasma who were selected from the outpatient dermatology clinic of Menoufia University Hospital between June 2018 and April 2019. The details of our study were explained to all prospective participants; then, each signed a written informed consent form before study initiation. The study protocol was approved by the human rights research ethics committee at Menoufia University and was conducted in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (revised in 2000).

We included 30 Egyptian women, aged older than 18 years, presenting with melasma who had not used any treatment (topical or systemic) for melasma within the previous month. We excluded those having any dermatological diseases other than melasma, bleeding disorders, thyroid disorders, or allergic reaction to any component of the prescribed drugs. Also, pregnant and lactating women and those using contraceptive pills and/or photosensitizing drugs were excluded.

Procedure. Each patient in our study was subjected to complete history-taking, skin phototyping,11 and general and complete dermatological examination. Patterns of melasma were identified (e.g., malar, centrofacial). The severity of melasma on each side of the face (right and left) was assessed using the Hemi-melasma Area and Severity Index (hemi-MASI) score,12 by which we scored the following: the area of involvement (A) (0=0%, 1=1%–9%, 2=10%–29%, 3=30%–49%, 4=50%–69%, 5=70%–89%, 6=90%–100%); darkness (D) (0=normal skin color, 1=slight hyperpigmentation, 2=mild visible hyperpigmentation, 3=marked hyperpigmentation, 4=severe hyperpigmentation); and homogenecity (H) (0=minimal, 1=slight, 2=mild, 3=marked, 4=severe) on each side of the face. Thus, the hemi-MASI score=forehead, 0.15 × (D+H) × A + malar, 0.30 × (D+H) × A + chin, 0.05 × (D+H) × A.

A dermoscopic examination was performed for each side of the face for all patients before and after treatment sessions using the Dermlite DL3 dermoscope (3GEN Company, Juan Capistrano, California) in a polarized mode. Images were captured using a P10 camera with dual lenses (Huawei Technologies Company, Shenzhen City, China). During the dermoscopic examination, pigment color, pattern of pigmentation, and vascularity were assessed. Melasma was considered epidermal when a regular brownish pigment network was noted, as dermal when a dark brown to bluish gray irregular pigmentation was noted, and as a mixed when the area of interest showed both features.

Every patient in this study underwent dermapen microneedling once per week for 12 weeks followed by the application of 5% MMI cream on the right side of the face and placebo cream on the left side.

MMI cream preparation. MMI was available in tablet form containing 5mg of MMI (tapazole tablet 5mg; Pfizer, New York, New York). The vehicle used in topical MMI formulations was a vanishing cream that consisted of stearic acid, triethanolamine, glycerine, sorbitol, and de-ionized water. The 5% MMI cream was obtained by adding the crushed tablets to the prepared vehicle.

Microneedling method. The patient’s face was cleansed with ethanol, then topical anesthetic cream (Pridocaine cream; GLOBAL NAPI Pharmaceuticals, 6th of October City, Egypt) was applied under occlusion for 30 minutes. A sterilized needle was put into the top of the hand piece of the dermapen; then, the length of the needles was adjusted to 0.25 to 0.5mm by turning the adjustment ring and the speed level ring was turned on. Circular, horizontal, and vertical motions were made four times with application of 5% MMI cream to the right side of the face and placebo cream to the left side. After the session, the skin was cleaned and cold packs were applied for five minutes. We instructed our patients to avoid skin rubbing and exposure to sun and to use sunscreen cream (SPF?30) every two hours during the daytime. In addition, they were told to apply the topical 5% MMI cream twice per day on the right side of the face and placebo on the left side immediately from the day of the procedure.

For comparative study, two digital photographs from each patient were taken using the Huawei P10 camera with dual lenses of 20 megapixel monochrome and 12 megapixel, one in the first visit and the other a week after the last session. The face was cleaned before photographing to prevent reflection. These photos were assessed by three independent investigators. Based on the average of their evaluations, the degree of clinical improvement was evaluated and classified as 4=poor (0%–25% lightening), 3=fair (26%–50% lightening), 2=good (51%–75% lightening), or 1=excellent (>75% lightening).

One week from the last session, the therapeutic efficacy was assessed by digital photography assessment as previously mentioned, hemi-MASI score reassessment, as done in the pretreatment period, and percent of hemi-MASI score improvement, evaluated by calculation of the difference between the hemi-MASI score values before and after treatment. This difference was divided by the pretreatment hemi-MASI score value and multiplied by 100. The following equation was used (hemi-MASI score before treatment – hemi-MASI score after treatment / hemi-MASI score before treatment × 100). The response to treatment was graded according to the calculated percent as follows, no response (no improvement), mild response (< 25% improvement), moderate response (25%–49% improvement), good response (50%–74% improvement), and very good response (?75% improvement).13

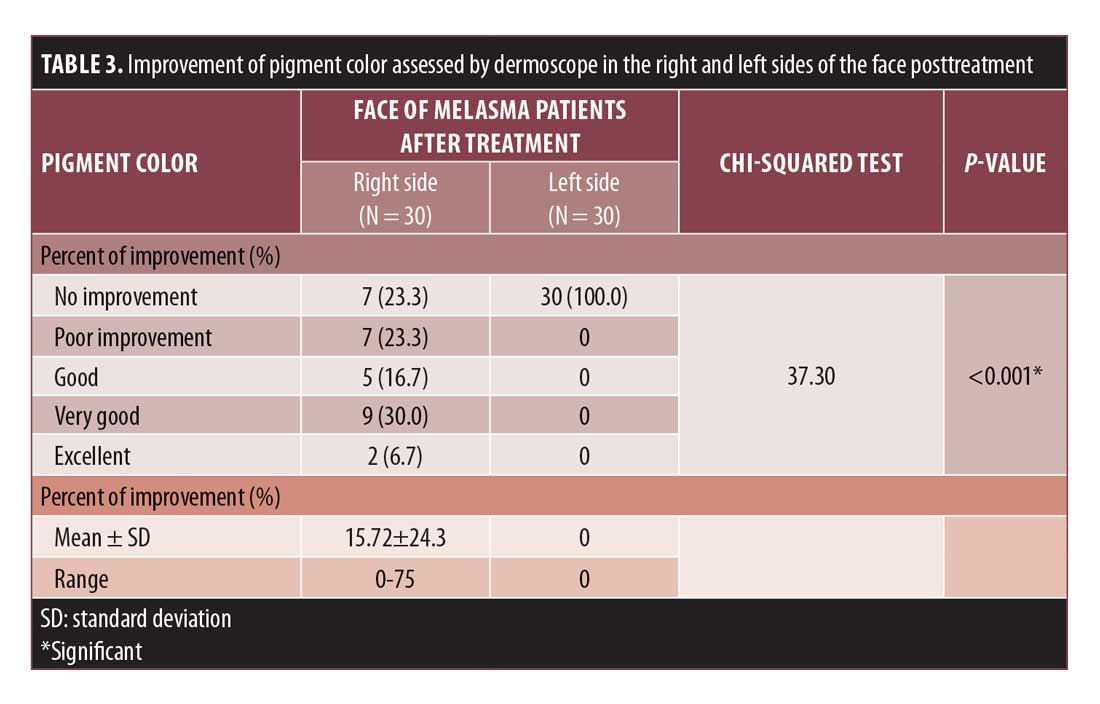

During the demoscopic reevaluation, pigment color improvement was graded as excellent (> 75% lightening), very good (51%–75% lightening), good (26%–50% lightening), poor (1%–25% lightening), or no improvement (0%).

Finally, patient’s satisfaction was classified as poor (0%–25% lightening), fair (26%–50% lightening), good (51%–75% lightening) and excellent (> 75% lightening).

For the safety evaluation of MMI, quantitative measurements of serum thyroid, stimulating hormone (TSH) levels were performed before the first session and one week after the last session using the Immulite 1000 analyzer (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a solid-phase two-site chemiluminescent immunometric assay.14 Also, any adverse effects noticed by the patient and/or the doctor—for example, morbid erythema (> day), intolerable pain, and/or hyperpigmentation—during and in between sessions was reported.

The patients were followed up with every month for three months after the last session to assess whether there was any recurrence.

Results

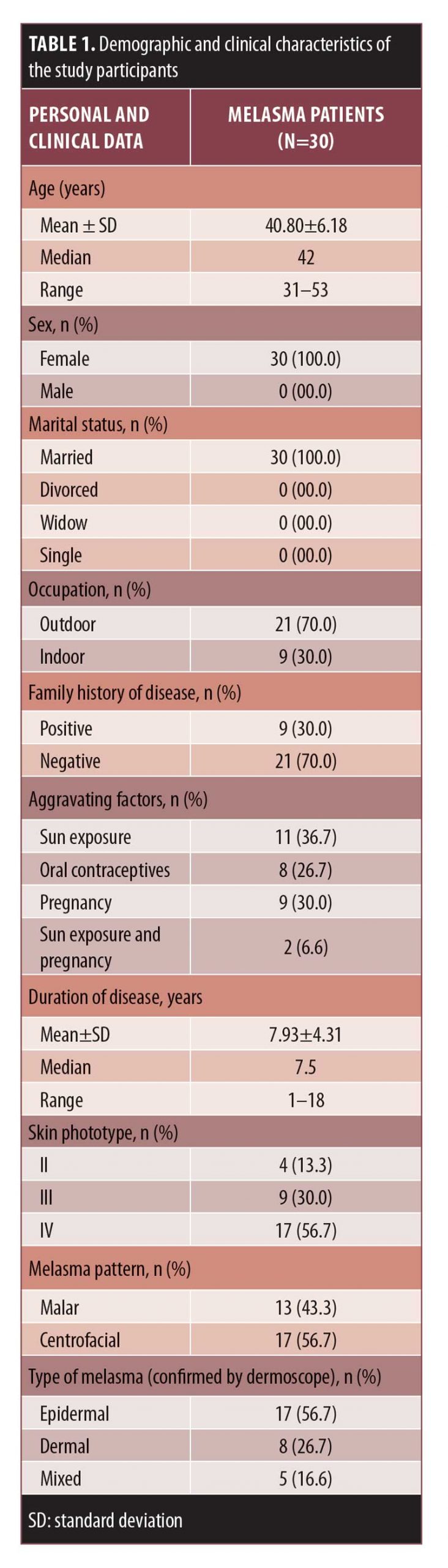

Personal and clinical data. We included 30 female patients with melasma, aged 31 to 53 years old. The clinical criteria of these patients are shown in Table 1.

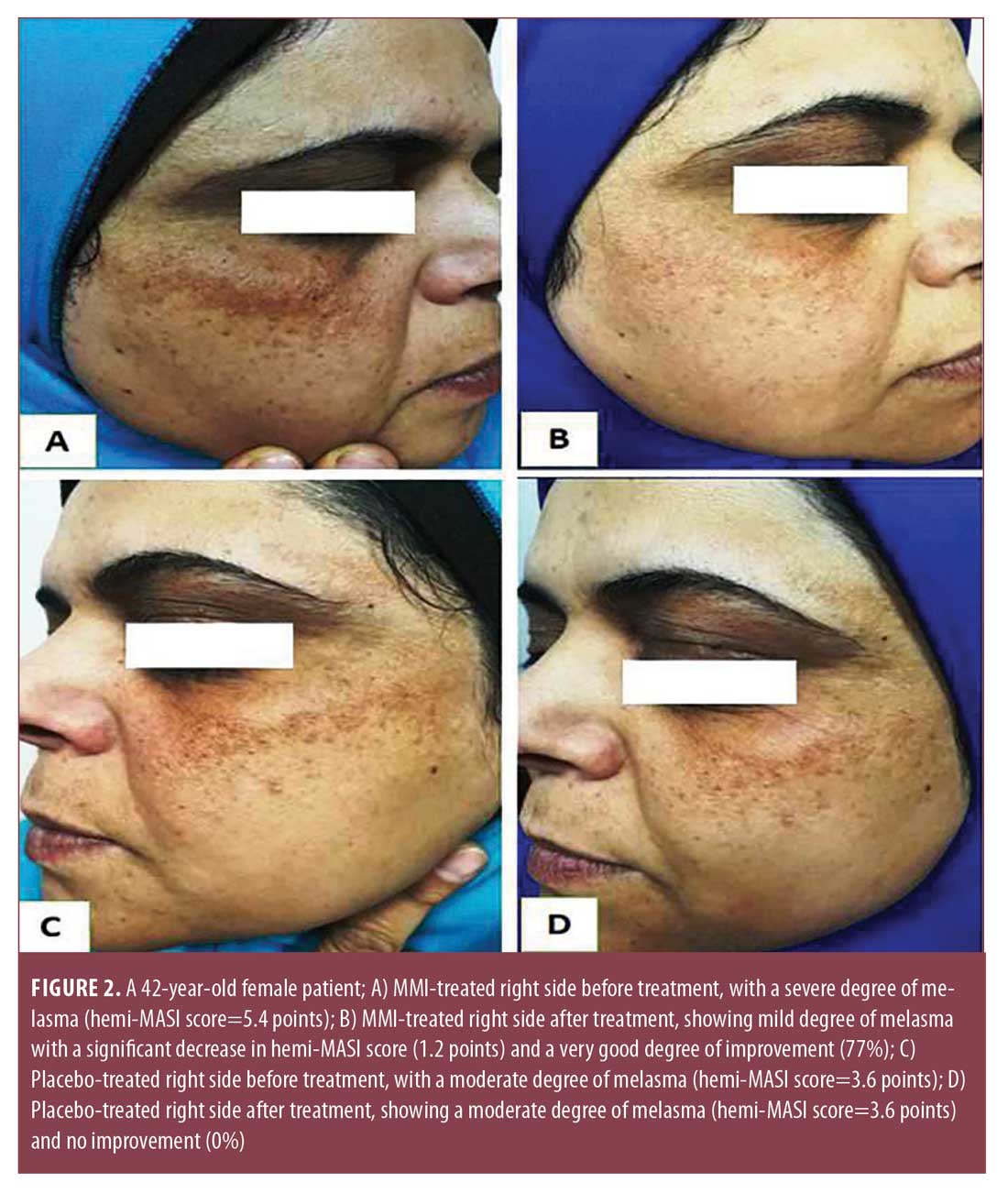

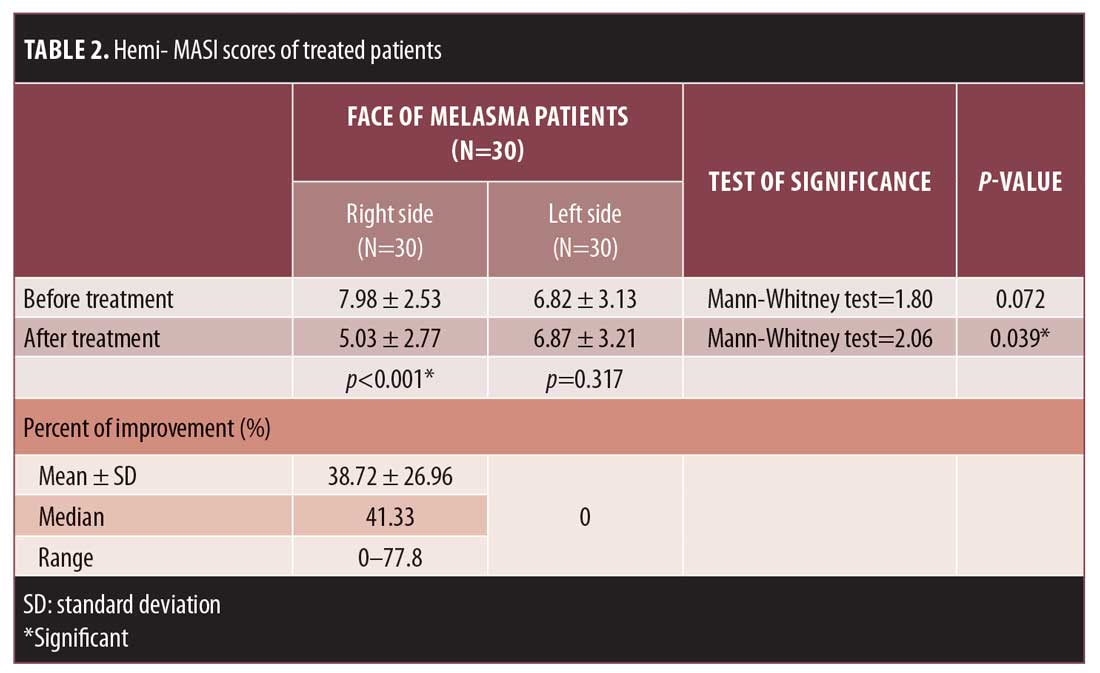

Hemi-MASI score results. Before treatment, hemi-MASI scores in the right and left sides were comparable (p=0.072). One week after the last session, melasma showed clinical improvement in the right side of the face (Figures 1A, 1B, and 2A, and 2B) and achieved a significant decrease in hemi-MASI score (p<0.001) that was greater than that for left (placebo) side (p=0.039) (Table 2). There was no clinical improvement in the left side (Figures 1C, 1D, 2C, and 2D).

Percentage of hemi-MASI score improvement. After treatment, 10 percent, 37 percent, 20 percent, and 10 percent of the patients demonstrated very good, good, moderate, and mild improvement, respectively, in the condition of their MMI-treated sides; no improvement was observed on the left side of the face. The mean percentage of hemi-MASI score improvement in the right side was 38.72%±26.96%, while that for the left side was 0% (Table 2).

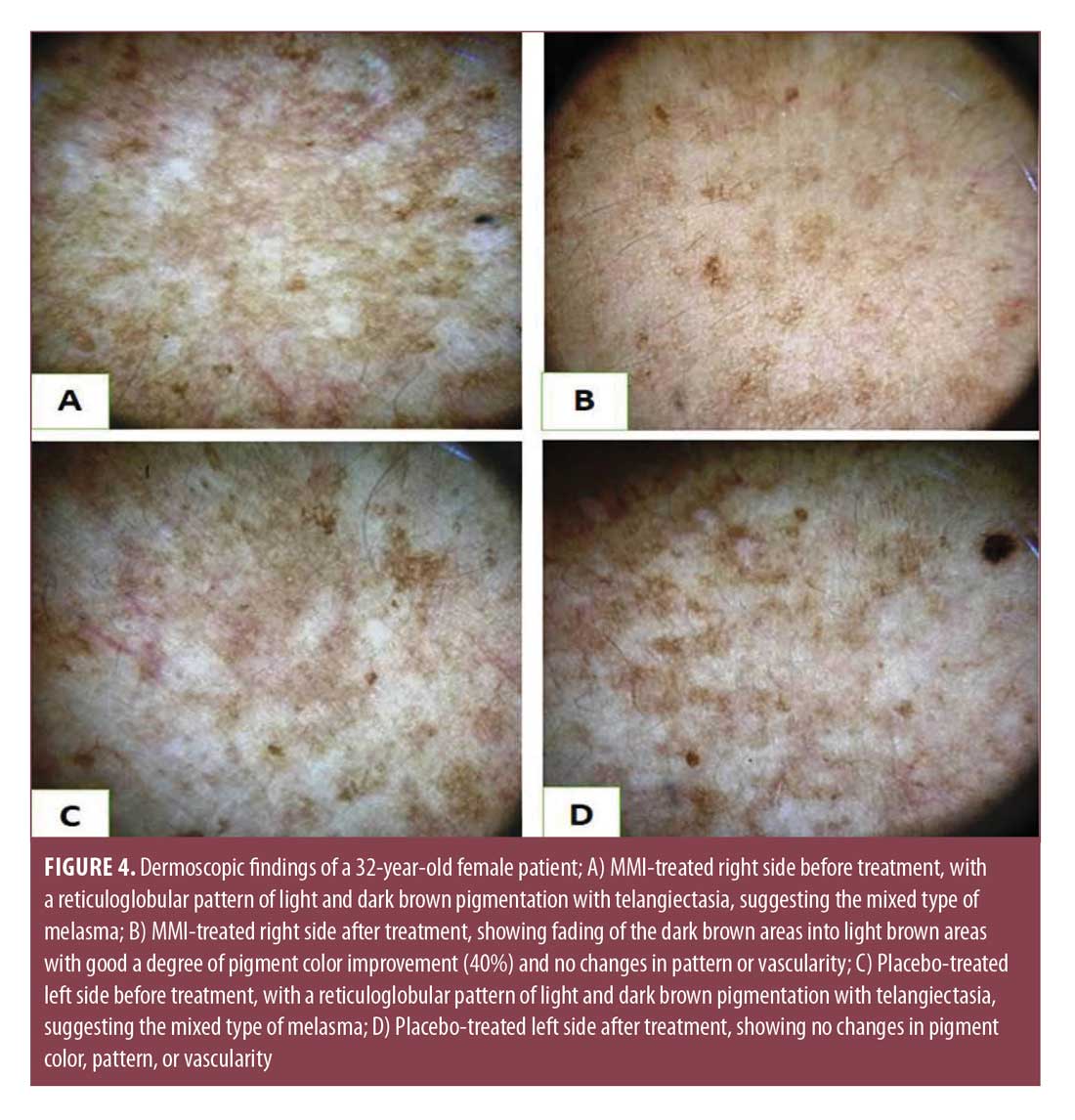

Results of dermoscopic study. Before treatment, the descriptive data of dermoscopic features of melasma patients were identical in both the right (Figures 3A and 4A) and left (Figures 3C and 4C) sides of the face. The observed pigment was brown in 17 (56.7%), dark brown to bluish gray in eight (26.6%), and dark brown and light brown areas in five (16.7%) cases, respectively. The dermoscopic patterns observed were reticuloglobular in 14 (46.7%), reticuloglobular with arcuate structures in 11 (36.6%), granular pigment on background of reticular pigment in three (10%), and unpatterned in two (6.7%) cases. Telangiectasia was observed in 14 (46.7%) patients.

After treatment, dermoscopic examination of the right sides (Figures 3B and 4B) showed fading of pigment color with no changes in pattern or vascularity, while the left side (Figure 3D, 4D) showed no changes in pigment color, pattern, or vascularity. The improvement percent in pigment color was 15.72%±24.3% in the right MMI-treated sides versus 0% in the left sides (Table 3).

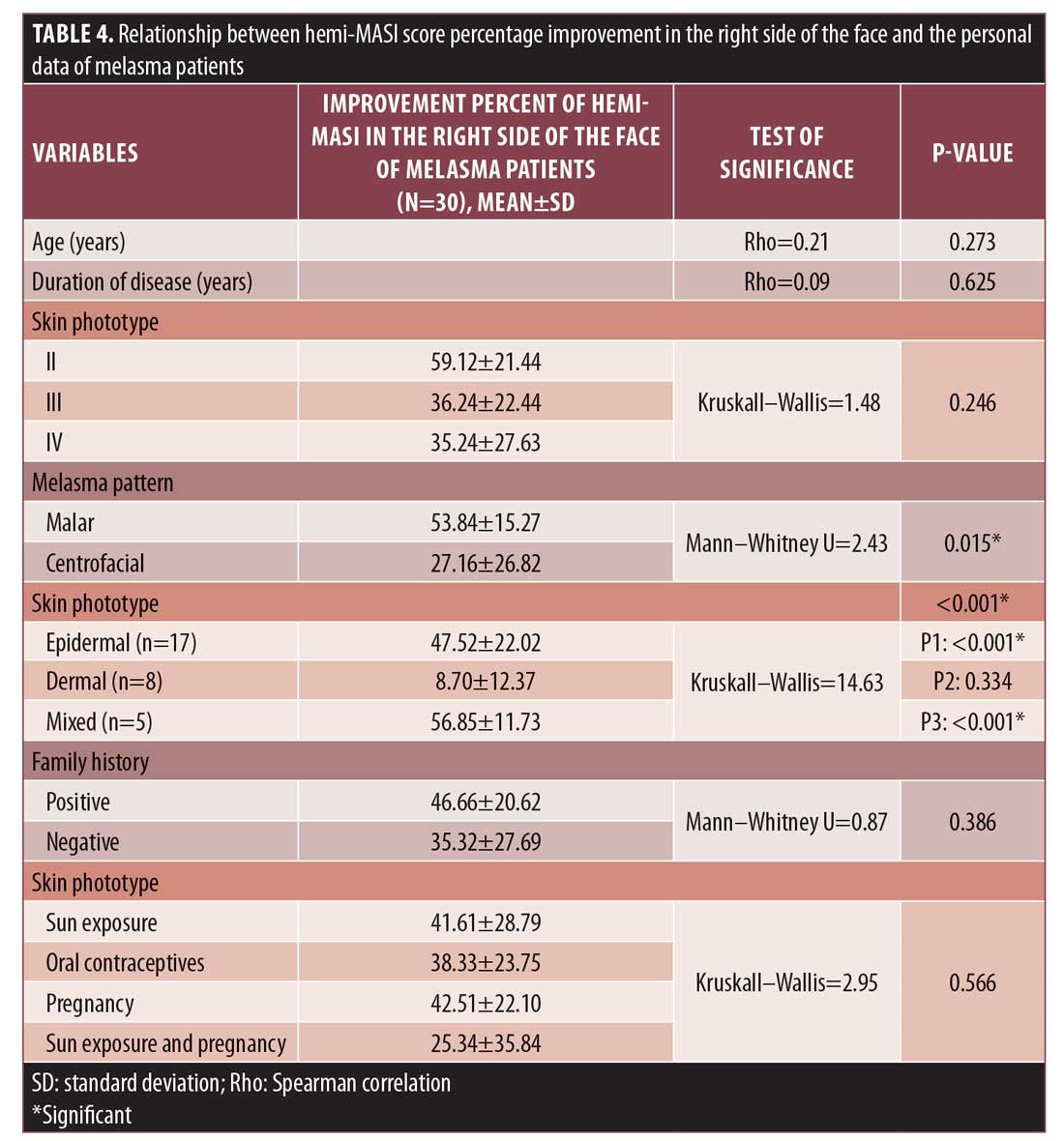

Relationship between the percentage of right-side hemi-MASI score improvement and studied parameters. The percentage of improvement in hemi-MASI scores was significantly observed in malar pattern (p=0.015) and epidermal and mixed types (p<0.001) (Table 4).

Patient satisfaction results. For their right sides, three patients (10%) reported excellent, 11 (36.7%) reported good, seven (23.3%) reported fair, and nine (30%) patients reported poor degrees of satisfaction; on the other hand, all patients (100%) reported poor degrees of satisfaction for their left sides (p<0.001) (Table 5).

Side effects. MMI was relatively a safe drug in this study, as morbid erythema (lasting >24 hours) was observed in one patient and post inflammatory hyperpigmentation in both sides of the face was detected in another patient. These side effects could be the result of the procedure and not the topically used preparations. Additionally, none of the patients showed any significant alterations in the level of TSH, with a mean value of 1.2±0.55 uIU/mL before and 1.23±0.67 uIU/mL after the study.

Recurrence rate. Only nine patients attended our clinic for follow-up (three months after the last session). Recurrence was recorded in two of these nine patients. However, these two patients did not protect themselves from sun exposure.

Discussion

To best of our knowledge, this study may be the first to investigate and report the efficacy and safety of MMI in the treatment of melasma through dermapen-transported microneedling sessions plus topical (MMI 5% cream) use in between sessions in an Egyptian population.

Microneedling is a potentially painless, safe, and effective procedure for transdermal drug delivery.15 In this study, we used dermapen skin microneedling as a physical approach to increase transdermal MMI delivery, by which a better therapeutic response to treatment might be attributed to the uniform and deep delivery of the used medication through the created microchannels.16

MMI inhibits the peroxidase existing in cutaneous melanocytes and inhibits the metabolization of many melanin intermediates, including dihydroxyindole, dihydroxy-phenylalanine, and benzothiazine. Consequently, MMI interferes with important steps in melanin pigment biosynthesis of both eumelanin and pheomelanin.6

Additionally, MMI was demonstrated to inhibit mushroom tyrosinase enzyme.17 Thus, MMI might theoretically interfere with the hydroxylation of tyrosine to dihydroxy-phenylalanine in melanocytes, which is the key step in melanin biosynthesis. Being an inhibitor of both tyrosinase and peroxidase, MMI acts on many steps during the process of melanogenesis, suggesting its possible role as a mono-therapy as well as an adjuvant to other melasma treatment agents.7

Moreover, it has been shown that MMI reduces ultraviolet-induced erythema, providing sun-protective skin action that adds to its depigmenting effect.7

At the end of this study, we observed a clinical improvement and a significant decrease in hemi-MASI scores in the right MMI-treated side of the face. Moreover, the degree of hemi-MASI score improvement percent in the MMI-treated side of the face revealed that 10 percent and 36.7 percent of our cases achieved very good and good responses to treatment, respectively.

The use of dermoscopy in melasma has many advantages: it is more accurate than Wood’s light and less invasive than histopathology.18 Parallel to the clinical improvement, dermoscopic evaluation for the right MMI-treated side of the face showed marked improvement in pigment color. Unfortunately, there are no similar trials that have used dermapen sessions or dermoscopy. Also, only a few studies have been published in which MMI 5% cream was topically used and these studies also did not use dermoscopy.2,8–10

Malek et al8 reported two melasma hydroquinone-resistant cases were improved after eight weeks of using topicalMMI 5% cream. Also, Atefi et al9 reported a statistically significant decrease in the MASI score mean value following the administration of MMI 5% cream once nightly for eight weeks by 25 Iranian patients with melasma, which was more effective than 2% hydroquinone. Conversely, Gheisari et al2 concluded that MMI 5% cream is not as effective as hydroquinone. However, the comparison between topical use of 5% MMI cream and 4% kojic acid suggested the superiority of 5% MMI cream.10

Three (10%) and 11 (36.7%) of our studied patients recorded excellent and good degrees of satisfaction, respectively, in the MMI-treated side of the face. Also, considerable degrees of patients satisfaction were observed with topical use.9,10

In this study, patients with the epidermal and mixed types of melasma achieved significantly greater improvement than those with the dermal type. This is a finding that supports the idea that the dermal variant of melasma is quite resistant to therapy.19 Also, patients having the malar pattern of melasma showed significant improvement, as most of our studied cases with malar patterning were of the epidermal type.

Minor adverse effects including erythema and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation were observed in two of the studied cases. Xerosis,2 burning, and itching10 have also been reported with use of topical MMI.

As the peroxidase enzyme is involved in the thyroxin biosynthesis, it was important to investigate the transdermal absorption of MMI to determine if it affects thyroid function. In the present study, serum TSH levels displayed a nonsignificant change between before and after treatment, indicating no impairment in thyroid function. Also, Kasraee et al5 demonstrated no change in the thyroid function tests (serum TSH, T3, and T4) after six weeks of daily MMI 5% cream. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction is defined as abnormal TSH levels with free thyroid hormone concentrations within the reference range;20 hence, we selected TSH for analysis. We may conclude, however, that topical MMI is a relatively safe drug with only minor adverse effects.

To avoid recurrence of melasma, actions including sun avoidance and regular use of broad-spectrum sunscreen should be recommended but may be difficult for many patients to comply with, especially those with low socioeconomic levels.21 Unfortunately, not all of our patients were cooperative and many didn’t attend during the follow-up visit. Only two of the nine patients who attended showed recurrence and both reported that they didn’t use sunscreen regularly.

We recommend that further studies involving larger populations be performed to confirm our results and address the appropriate MMI dosage, frequency of application, and long-term benefits. Adequate follow-up to detect any recurrence or late adverse effects is also recommended. Trials to evaluate the current method against another treatment modality may identify any additive effects in the search for better melasma treatment.

Conclusions

To our knowldege, our study describes a new strategy in the treatment of melasma through the use of MMI delivered by dermapen skin microneedling sessions in combination with topical MMI 5% cream as a depigmenting agent. According to our results, this combination therapy is a safe, effective, and tolerable treatment for melasma.

References

- Kaliterna D, Kristina Z and Kovacevic I. Melasma—review of current treatment modalities and efficacy assessment of a new resorcinol-based topical formulation. J Clin Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;(3):2576–2826.

- Gheisari M, Dadkhahfar S, Olamaei E, et al. The efficacy and safety of topical 5% methimazole vs 4% hydroquinone in the treatment of melasma: a randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19(1):167–172.

- Chatterjee M, Vasudevan B. Recent advances in melasma. Pigment Int. 2014;1(2):70–80.

- Kasraee B, Handjani F, Parhizgar A, et?al. Topical methimazole as a new treatment for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: report of the first case. Dermatology. 2005;211(4):360–362.

- Kasraee B, Safaee Ardekani GH, Parhizgar A, et al. Safety of topical methimazole for the treatment of melasma. Transdermal absorption, the effect on thyroid function and cutaneous adverse effects. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;21:300–305.

- Kasraee B. Depigmentation of brown Guinea pig skin by topical application of methimazole. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118(4):205–207.

- Kasraee B, Hugin A, Tran C, Sorg O, Saurat JH. Methimazole is an inhibitor of melanin synthesis in cultured B16 melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(5):1338–1341.

- Malek J, Chedraoui A, Nikolic D, Barouti, et al. Successful treatment of hydroquinone-resistant melasma using topical methimazole. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26(1):69–72.

- Atefi N, Behrangi E, Nasiripour S, et al. A double blind randomized trial of efficacy and safety of 5% methimazole versus 2% hydroquinone in patients with melasma. J Skin Stem Cell. 2017;4(2):e62113.

- Yenny SW. Comparison of the use of 5% methimazole cream with 4% kojic acid in melasma treatment. Turk Dermatoloji Dergisi. 2018;12(4):167–171.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin type I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(6):869–871.

- Wang X, Li Z, Zhang D, Li L, Sophie S. A double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of a new skin whitening combination in patients with chloasma. Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications. 2014;4(2):92–98.

- Budamakuntla L, Loganathan E, Suresh DH, et al. A randomised, open label, comparative study of tranexamic acid microinjections and tranexamic acid with microneedling in patients with melasma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6(3):139–143.

- Nicoloff J, Spencer C. The use and misuse of sensitive thyrotropin assays. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71(3):553–558.

- Shivanand P, Binal P, Mahalaxmi R, et al. Microneedle: an effective and safe tool for drug delivery. Int J Pharmtech Res. 1(4): 1283–1286.

- Kalluri H, Kolli CS, Banga AK. Characterization of microchannels created by metal microneedles: formation and closure. AAPS J. 2011;13(3):473–481.

- Andrawis A, Kahn V. Effect of methimazole on the activity of mushroomtyrosinase. Biochem J. 1986;235(1):91–96.

- Ibrahim ZA, Gheida SF, El Maghraby GM, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of combinations of hydroquinone, glycolic acid, and hyaluronic acid in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14(2): 113–123.

- Lee JH, Park JH, Lim SH, et al. Localized intradermal microinjection of tranexamic acid for treatment of melasma in Asian patients: a preliminary clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(5):626–631.

- Baumgartner C, da Costa BR, Collet T et al. Thyroid function within the normal range, subclinical hypothyroidism, and the risk of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2017;136(22):2100–2116.

- Prignano F, Ortonne JP, Buggiani G, et al. Therapeutical approaches in melasma. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25(3):337–342