J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(1):38–46

by Siriorn Udompanich, MBchB, MSc and Vasanop Vachiramon, MD

by Siriorn Udompanich, MBchB, MSc and Vasanop Vachiramon, MD

Dr. Udompanich and Dr. Vachiramon are with the Division of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand.

Funding: No funding was provided for this study.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Acquired macular pigmentation of unknown etiology is a new umbrella term that encompasses a group of diseases that, while having similar clinical and histological features, their true entities are controversial, and a global consensus regarding these conditions is still lacking. The conditions comprised by the term are ashy dermatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, lichen planus pigmentosus, and idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation. In this review, we compare the clinical and histological features of these conditions that comprise aquired macular pimgentation of unknown etiology, as well as review their responses to treatment.

Keywords: Hypermelanosis, hyperpigmentation, lichen planus, pigmentation disorders

In clinical practice, the terms ashy dermatosis (AD), erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) and idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP) are potential differential diagnoses when encountering hyperpigmentation of the skin with unknown etiology and without any sign of preceding or concurrent inflammation. A definite diagnosis, however, might prove to be challenging, as these conditions contain overlapping clinical and histological features, and it seems the terms are often used interchangeably. It is worthwhile to update the available information on this group of diseases in order to improve treatment outcomes and patient knowledge of disease prognosis.

Recently, AD, EDP, and IEMP have been grouped together under the umbrella term acquired macular pigmentation of unknown etiology. Using this classification, AD, EDP, and IEMP are all considered to have unknown etiologies, with AD and EDP separated according to the existence of an erythematous border. LPP, however, was classified as having a known etiology.1 Although LPP has a recognized connection with lichen planus, its pathogenesis and triggers are still largely unproven. Thus, in our opinion, LPP should also be considered to have an unknown etiology and be included under the umbrella term.

In an attempt to clarify the similarities and differences between the individual conditions that make up this disease group, we collected and reviewed all relevant publications and summarized clinical and histological features, current diagnostic criteria, and available treatment options of each condition. However, the answer as to whether these conditions truly represent unique clinical entities or are different variations of the same disease is still inconclusive.

Ashy Dermatoses and Erythema Dyschromicum Perstans

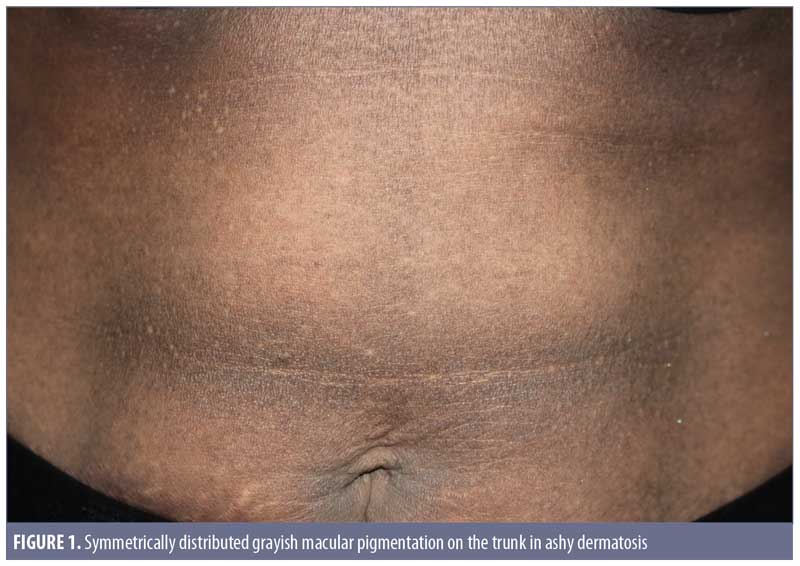

Clinical features. Ashy dermatoses. The recognition of hyperpigmentation of the skin without any preceding inflammatory skin lesions, proven triggers, or causative agents can be dated back several years. The term ashy dermatosis was first used by Ramirez in 1957 to describe asymptomatic macular lesions with various “shadings of grayish pigmentation,” with an insidious onset and no sex predilection, in young adult patients.2 These symmetrical, hyperpigmented lesions are typically located on the trunk, neck, and upper extremities, and are most commonly observed on patients with Fitzpatrick skin type IV3 (Figure 1). The lesion size can vary from 1-cm macules to very large patches. Itchiness has been reported as a symptom by approximately 16 percent of the patients.3

Erythema dyschromicum perstans. In 1961, shortly after Ramirez’s publication, Convit et al4 observed similar lesions to those of AD but with raised, narrow, erythematous borders that characteristically disappear in a few months. Later, Sulzberger5 proposed the term erythema dyschromicum perstans, and commented that the narrow red border indicates an active phase. While most current literature reports AD and EDP as one entity, some researchers, based on diagnosis algorithms, consider the erythematous border to be a distinguishing feature in EDP.1,6 Of note, authors of a retrospective study of 68 patients with EDP reported that only 17.6 percent of the patients observed the peripheral erythematous border.3 This finding indicates that the presence of an erythematous border can vary from patient to patient, and whether it is present relies on the observations of the patient and/or timing of consultation. EDP has been diagnosed in prepubertal children, as well as adults, and shares numerous overlapping features with idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (discussed later). 7,8

Histological features. Biopsies taken from AD/EDP in numerous studies have shown similar histopathological findings. The epidermis can appear as hyperkeratotic or atrophic, sometimes with apoptotic keratinocytes. Frequently, there is basal vacuolar degeneration and a focal or lichenoid pattern with colloid bodies along the dermoepidermal junction. Primary histological findings include pigment incontinence and melanophages in the dermis, along with mild-to-moderate superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration. According to Chang et al,3 EDP can be subdivided into active lesions with predominant basal vacuolar degeneration and lymphocytic infiltration and inactive lesions with melanophages and pigment incontinence in the dermis.3 Table 1 summarizes the main clinical and histological findings of AD/EDP from previous studies.

Etiology. Though the cause of AD/EDP is unknown, it is plausible that multiple environmental and genetic factors participate in the pathogenesis of the disease. One study of Mexican patients showed that AD has an important genetic predisposition and is associated with HLA-DR4 subtype*0407.9 Another study detected an expression of cluster of differentiation (CD) 54 and major histocompatibility complex class II (HLA-DR) in the keratinocyte basal cell layer , as well as an increase in the expression of CD36 in the strata spinosum and granulosum and CD69 and CD94 in the dermal cell infiltrate.10

So far, reported triggers of AD/EDP include parasite infection, chemicals (e.g., ammonium nitrate, fungicide, pesticide, X-ray contrast, cobalt allergy, oral antibiotics, benzodiazepines endocrinopathies).7,11–14 Recently, Chua et al15 reported three cases of ashy dermatoses induced by omeprazole.15

Diagnostic criteria and classification. There is currently no accepted or widely implemented diagnostic criteria for AD/EDP used in clinical practice. However, some practical recommendations have been made in the past. Zaynoun et al6 proposed a simple classification for AD, and described the condition as idiopathic, eruptive, hyperpigmented macules, irrespective of the histological presence of interfacial dermatitis at the time of examination. A diagnosis of EDP is considered in patients with lesions similar to those of AD, but with a history of or active presence of erythematous borders. Other conditions—namely LP, LPP, actinic LP, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, drug-induced melanodermas, and mastocytosis—have been classified as “simulators” of AD.6

After studying 68 patients with EDP, Chang et al3 proposed a list of clinical signs in the diagnosis of AD/EDP. Unlike Zaynoun et al,6 Chang et al considered AD and EDP to be the same entity and recommended that a diagnosis of AD/EDP is warranted when the following criteria are met:3

- Except for occasional slight itching, the lesions remain asymptomatic.

- Some of the lesions have an easily observable, nonelevated, erythematous border.

- The lesions can appear on exposed or unexposed areas.

- The lesions do not involve the mucosa.

- The lesions rarely improve.

Treatment and prognosis. Various oral and topical treatment modalities have been given to patients, but often with disappointing outcomes (Table 1). The most popular agent used is still topical corticosteroid, followed by triple-combination creams (e.g., fluocinolone acetonide, hydroquinone, tretinoin).3 Some positive results were reported with clofazimine and dapsone,16,17 while isotretinoin and various pigment lasers, in recent case reports, have shown significant lesion clearance.18–20 Additional, well-controlled clinical trials are necessary to determine the most effective treatment. Overall, a majority of patients (49%) did not show any significant improvement after a follow-up period of more than one year.

Lichen Planus Pigmentosus

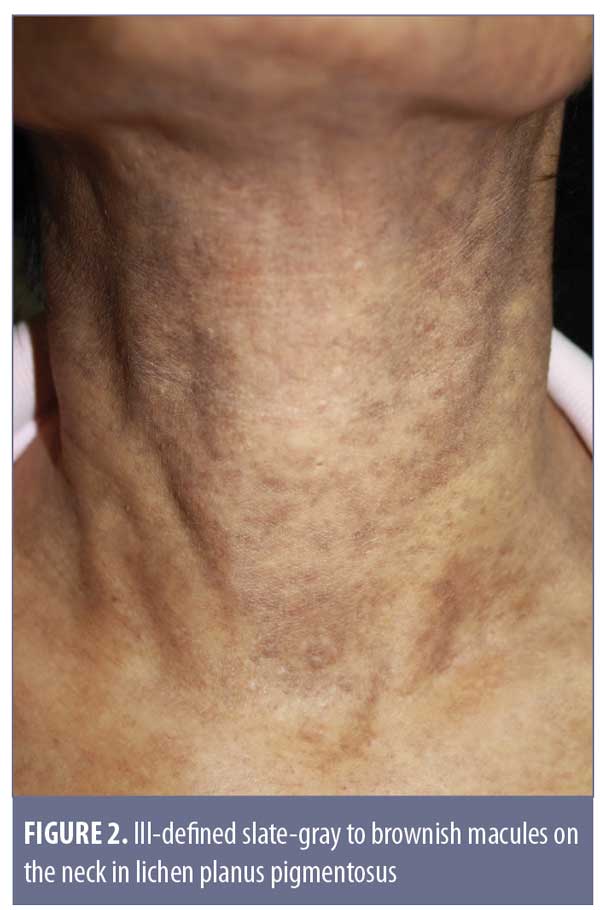

Clinical features. Originally described in India,21 LPP has been reported in various parts of the world, including Mexico, Kuwait, and Turkey.18,21–25 LPP presents as ill-defined, slate-gray to brownish-black macules found on sun-exposed areas, predominantly on the face and neck, flexural folds, and, rarely, on oral mucosa (Figure 2).18 The insidious hyperpigmentation occurs in adults with Fitzpatrick Skin Types III to IV and occasionally becomes mildly pruritic. An interesting feature of LPP, which distinguishes it from other conditions in this group, is that it can have different morphological patterns. The rash has been described as diffuse, reticular, blotchy, perifollicular, follicular, linear,23 and zosteriform. The presence of LPP on intertriginous areas are termed lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPP-inversus).22

Despite LPP sharing similar features with AD/EDP, Vega et al24 found significant clinical differences and concluded that LPP and AD/EDP are indeed two separate conditions.24 The shade of rash in LPP tends to be dark brown instead of grayish, the distribution is less likely to be symmetrical, and associated pruritus is more common.24 In addition, involvement of the oral mucosa, previously described as having a diffuse or speckled pattern, is exclusive to LPP.26 Nevertheless, the differentiation between AD/EDP and LPP is still a subject of controversy. Daoud and Pitterlkow27 report that AD/EDP and LPP represent an overlap in the phenotypic spectrum of lichenoid inflammation in darkly pigmented skin.27

Histological features. A review of skin biopsies obtained from 65 patients with LPP showed that perivascular infiltration, basal cell degeneration, and presence of melanophages were the most common findings (81.5%, 78.5%, and 63%, respectively).24 Other epidermal changes include hyperkeratosis and atrophy. In general, histological findings of LPP resemble those found in AD/EDP and thus cannot be differentiated based on histological basis alone.24 Table 2 summarizes the main clinical and histological findings of LPP from previous studies.

Etiology. LPP is frequently associated with lichen planus (ranging from 9–27%) and hepatitis C infection (up to 60.6%), contributing to the theory that LPP is a rare variant of lichen planus.18 Apart from that, patients have reported a history of using mustard oil, amla oil (a common remedy used for body massage and hair dressing in India), henna, and hair dye.18,26 However, a temporal relationship between the use of these agents and the development of LPP could not be established. Approximately 17.7 percent of the patients diagnosed with LPP experienced darkening of the pigmentation after exposure to sunlight.26 This finding, together with its predilection for sun-exposed areas, supports the notion that ultraviolet radiation might play a role in the pathogenesis of LPP, perhaps affecting an unknown photosensitizing agent. Other conditions that have been linked to LPP are frontal fibrosing alopecia, acrokeratosis of Bazex, and minimal change nephrotic syndrome.28–31

Diagnostic criteria. Until now, there have not been proposed diagnostic criteria or classifications for LPP.

Treatment and prognosis. Similar to AD/EDP, LPP is refractory to treatment. However, topical and systemic corticosteroids, oral vitamin A, and pigment lasers have resulted in favorable outcomes.32–35 In a prospective study of 33 patients with LPP, 53.8 percent showed improvement in pigmentation after 16 weeks of topical tacrolimus.18 Interestingly, in a small number of patients with positive hepatitis C virus serology, a significant improvement was achieved after a year of antiviral medication.18

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation

Clinical features. In 1978, the term idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation emerged.36 Compared with those of AD/EDP and LPP, IEMP lesions are smaller, well-defined, discrete, hyperpigmented macules, often less than 3cm in diameter (Figure 3). They appear on the trunk and extremities, almost exclusively in healthy young children and adolescents, without any associated pruritus or involvement of the oral mucosa.37 IEMP lesions can vary from brown to ash-colored, and sometimes the surface of the lesion is velvety with papillomatosis, similar to acanthosis nigricans.38 IEMP can be diagnosed with or without the appearance of papillomatosis.

The most distinguishing feature of IEMP is that the lesions resolve without treatment within several months to years. Interestingly, the condition seems to exist in both dark and light skin phototypes, as opposed to AD/EDP and LPP, which more typically present in individuals with darker skin. Torrelo et al7 and Silverberg8 both observed that young patients who develop AD/EDP are more likely to be Caucasian and the lesions seem to resolve spontaneously.7,8 This raises the suspicion that some of the reported cases of AD/EDP in younger Caucasian children might actually have been IEMP.

Histological features. IEMP is an epidermal, hypermelanotic condition, unlike AD/EDP or LPP. The most striking finding is increased melanin in the basal cell layer. Basal cell vacuolization and lichenoid reactions are always absent, and the inflammation in the dermis can be very mild with few melanophages.39 Table 3 summarizes the main clinical and histological findings of IEMP from previous studies.

Etiology. While the pathogenesis of IEMP remains unknown, the most logical theory links it to hormonal factors, due to its predominance in children and young adults.37 IEMP has also been hypothesized to be related to an autoimmune phenomenon, as described in a case report of a 33-year-old Caucasian woman with a history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis who developed biopsy-proven IEMP during her second pregnancy.40

Diagnostic criteria. Within the group of acquired macular pigmentation of unknown etiology, IEMP is the only condition with well-documented diagnostic criteria. The original criteria, proposed by Sanz de Galdeano et al41 include the following:

- Eruption of brownish, nonconfluent, asymptomatic macules involving the trunk, neck, and proximal extremities in children and adolescents

- Absence of preceding inflammatory lesions

- No previous drug exposure

- Basal cell layer hyperpigmentation of the epidermis and predominant dermal melanophages without visible layer damage or lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate

- Normal mast cell count.

Since the publication of these criteria, they have been used regularly in case reports.

- In 2007, Joshi et al39 reviewed 24 case reports of IEMP and proposed a revised diagnostic criteria that incorporates a papillomatosis variant and emphasizes the main histological findings.39 The new criteria are as follows:

- Eruption of brownish-black, discrete, nonconfluent, asymptomatic macules and/or slightly raised plaques that resemble acanthosis nigricans and involve the face, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities, with complete resolution after months to years

- Affects mostly children and adolescents (i.e., those in the first two decades of life)

- Epidermal hypermelanosis with or without papillomatosis as the main histological finding with an absence of dermal inflammation

- A lack of numerous dermal melanophages and no presence of interface changes (The presence of either of these is considered negative findings and might be considered to be against the diagnosis of IEMP.)

- Absence of preceding inflammatory lesions

- No previous drug exposure

- Normal mast cell count

Treatment and prognosis. IEMP has an unremarkable prognosis and is usually self-limited. The lesions will gradually resolve on their own, typically within a period of several months to a few years. So far, there is no documentation of any recurrences. This information might be useful when providing advice to patients or parents of young patients.

Following our review, we summarized the main similarities and differences of AD/EDP, LPP, and IEMP in Table 4.

Differential Diagnosis for Acquired Macular Pigmentation of Unknown Etiology

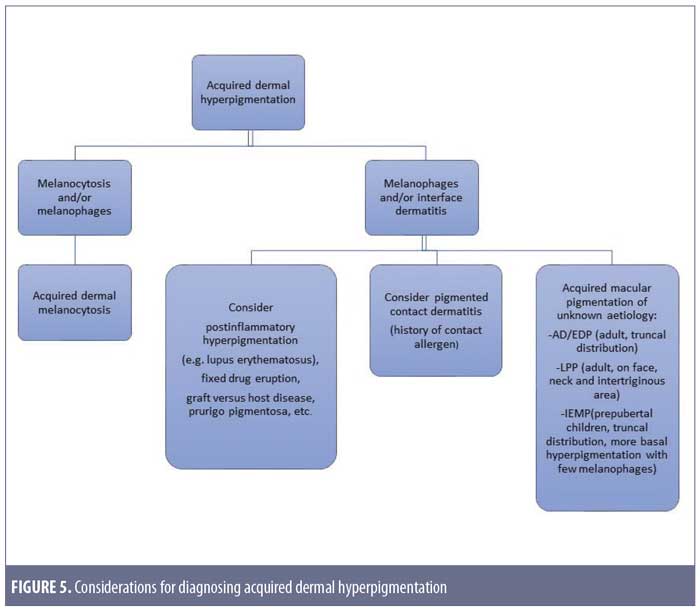

There is a wide range of differential diagnoses when patients present with hyperpigmentation of the skin, and clinicians can often make the correct diagnosis only after taking a history and performing a thorough physical examination. Occasionally, skin biopsies can aid in the diagnosis. Some dermatological conditions share similar features with AD/EDP, LPP, and IEMP and should be ruled out before considering this group of diseases. When melanocytosis and/or melanophages are seen on histology, acquired dermal melanocytosis, including the late-onset naevus of Ota or Ito, should be considered. Systemic conditions such as hyperthyroidism and Addison’s disease can also present with macular hyperpigmentation, as can effects from systemic drugs such as amiodarone and minocycline.1 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is common, especially after conditions like cutaneous lupus erythematosus, graft-versus-host disease, and prurigo pigmentosa.

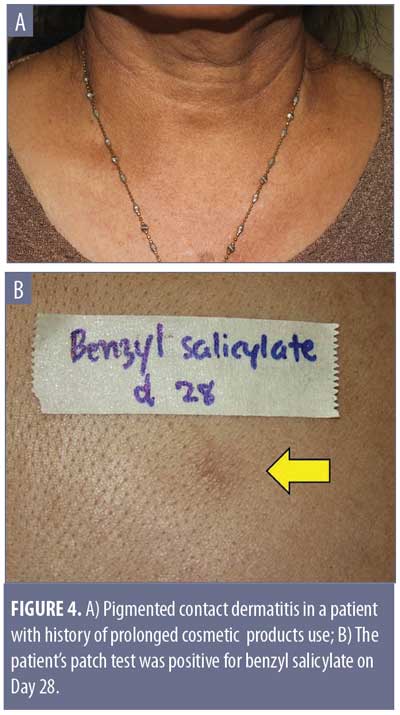

The most important condition to rule out is pigmented contact dermatitis or Riehl’s melanosis, as avoidance of the contact allergen is an essential part of the treatment plan. This rare noneczematous variant of contact dermatitis manifests as hyperpigmentation in dark-skinned individuals, resulting from repeated contact of a very small amount of allergen. It is believed that the amount of contact allergen is not enough to mount the usual epidermal spongiosis and inflammation of the skin, but instead causes basal liquefaction, gradually dropping melanin pigment to the upper dermis.42 The hyperpigmentation can be reticulated, with shades of slate gray, grayish brown, and bluish brown (Figure 4A). The lesions typically occur on the site of contact. Examples include over-covered areas in a patient allergic to an optical whitener in washing powder or on the face and neck in cases of a fragrance allergy.42 The most common allergens are detected in fragrances, cosmetics, textile dyes, washing powders, and rubber products. Examples include napthol AS (dye for textile), and hydroxycitronellal and benzyl salicylate (both fragrances) (Figure 4B).42 It is worthy to note that, unlike the typical contact dermatitis, the hyperpigmentation can persist even after discontinuation of exposure to the allergen.43

When a history of a possible contact allergen is gathered, patch testing might be the next logical step. A prospective study performed various screening patch tests on Israeli patients suspected to have pigmented contact dermatitis, revealing that the majority had a positive result with European standard series (16 out of 26 patients, 10 of whom were relevant), with fragrance mix being the most common allergen.44 In another study from Thailand, eight out of 10 patients with clinical pigmented contact dermatitis had a positive patch test result. The most common allergens were nickel sulfate hexahydrate, cobalt(II) chloride hexahydrate, and fragrance mix II.45

After taking into account these differential diagnoses, we would like to propose a simple approach to diagnosing acquired dermal hyperpigmentation, as shown in Figure 5.

Conclusion

The term acquired macular pigmentation of unknown etiology depicts a group of hyperpigmented conditions with overlapping features. AD and LPP share the same histological picture of pigmentary incontinence, basal vacuolization, and superficial perivascular infiltrate, but differ in terms of clinical pattern. IEMP, on the other hand, has more definite histological findings, mainly showing epidermal hypermelanosis with or without papillomatosis. A wide range of other systemic and dermatologic conditions should be included in the differential diagnosis, especially noneczematous pigmented contact dermatitis. Additional large-scale studies are required for the development of practical diagnostic criteria and treatment guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Poonkiat Suchonwanit for the preparation of illustrations.

References

- Chandran V, Kumarasinghe SP. Macular pigmentation of uncertain aetiology revisited: two case reports and a proposed algorithm for clinical classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58(1):45–49.

- Ramirez CO. The ashy dermatosis (erythema dyschromicum perstans). Epidemiological study and report of 139 cases. Cutis. 1967;3:244–247.

- Chang SE, Kim HW, Shin JM, Lee JH, Na JI, Roh MR, et al. Clinical and histological aspect of erythema dyschromicum perstans in Korea: A review of 68 cases. J Dermatol. 2015;42(11):1053–1057.

- Convit J, Kerdel-Vegas F, Rodriguez G. Erythema dyschromicum perstans. A hitherto undescribed skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1961;36:457–465.

- Kennedy BO, Epstein WL. Discussion. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:270-2.

- Zaynoun S, Rubeiz N, Kibbi AG. Ashy dermatoses—a critical review of the literature and a proposed simplified clinical classification. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(6):542–544.

- Silverberg NB, Herz J, Wagner A, Paller AS. Erythema dyschromicum perstans in prepubertal children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20(5):398–403.

- Torrelo A, Zaballos P, Colmenero I, et al. Erythema dyschromicum perstans in children: a report of 14 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(4):422–426.

- Correa MC, Memije EV, Vargas-Alarcon G, et al. HLA-DR association with the genetic susceptibility to develop ashy dermatosis in Mexican Mestizo patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(4):617–620.

- Baranda L, Torres-Alvarez B, Cortes-Franco R, et al. Involvement of cell adhesion and activation molecules in the pathogenesis of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatitis). The effect of clofazimine therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(3):325–329.

- Jablonska S. Ingestion of ammonium nitrate as a possible cause of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Dermatologica. 1975;150(5):287–291.

- Lambert WC, Schwartz RA, Hamilton GB. Erythema dyschromicum perstans. Cutis. 1986;37(1):42–44.

- Stevenson JR, Miura M. Erythema dyschromicum perstans. (Ashy dermatosis). Arch Dermatol. 1966;94(2):196–199.

- Zenorola P, Bisceglia M, Lomuto M. Ashy dermatosis associated with cobalt allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31(1):53–54.

- Chua S, Chan MM, Lee HY. Ashy dermatosis (erythema dyschromicum perstans) induced by omeprazole: a report of three cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(10):e435–e436.

- Bahadir S, Cobanoglu U, Cimsit G, et al. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: response to dapsone therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(3):220–222.

- Piquero-Martin J, Perez-Alfonzo R, Abrusci V, et al. Clinical trial with clofazimine for treating erythema dyschromicum perstans. Evaluation of cell-mediated immunity. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28(3):198–200.

- Al-Mutairi N, El-Khalawany M. Clinicopathological characteristics of lichen planus pigmentosus and its response to tacrolimus ointment: an open label, non-randomized, prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(5):535–540.

- Wang F, Zhao YK, Wang Z, et al. Erythema dyschromicum perstans response to isotretinoin. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(7):841–842.

- Wolfshohl JA, Geddes ER, Stout AB, Friedman PM. Improvement of erythema dyschromicum perstans using a combination of the 1,550-nm erbium-doped fractionated laser and topical tacrolimus ointment. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(1):60–62.

- Bhutani LK, Bedi TR, Pandhi RK, Nayak NC. Lichen planus pigmentosus. Dermatologica. 1974;149(1):43–50.

- Dizen Namdar N, Kural E, Pulat O, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: 5 Turkish cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(3):450–452.

- Vachiramon V, Suchonwanit P, Thadanipon K. Bilateral linear lichen planus pigmentosus associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Case Rep Dermatol. 2010;2(3):169–172.

- Vega ME, Waxtein L, Arenas R, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31(2):90–94.

- Sindhura KB, Vinay K, Kumaran MS, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus: a retrospective clinico-epidemiologic study with emphasis on the rare follicular variant. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(11):e142–e144.

- Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, Handa S, et al. A study of 124 Indian patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28(5):481–485.

- Pittelkow MRD, M.S. Lichen planus. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2012: 302.

- Berliner JG, McCalmont TH, Price VH, Berger TG. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):e26–e27.

- Dlova NC. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: is there a link?. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(2):439–442.

- Mancuso G, Berdondini RM. Coexistence of lichen planus pigmentosus and minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19(4):389–390.

- Sassolas B, Zagnoli A, Leroy JP, Guillet G. Lichen planus pigmentosus associated with acrokeratosis of Bazex. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(1):70–73.

- Bhutani LK, George M, Bhate SM. Vitamin A in the treatment of lichen planus pigmentosus. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100(4):473–474.

- Ghosh A, Coondoo A. Lichen planus pigmentosus: the controversial consensus. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61(5):482–486.

- Han XD, Goh CL. A case of lichen planus pigmentosus that was recalcitrant to topical treatment responding to pigment laser treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27(5):264–267.

- Kim JE, Won CH, Chang S, et al. Linear lichen planus pigmentosus of the forehead treated by neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser and topical tacrolimus. J Dermatol. 2012;39(2):189–191.

- Degos R, Civatte J, Belaich S. [Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (author’s transl)]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1978;105(2):177–182. Article in French.

- Jang KA, Choi JH, Sung KS, et al. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation: report of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(2 Suppl):351–353.

- Joshi R. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis: Report of nine cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73(6):402–405.

- Joshi RS, Rohatgi S. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation: A critical review of published literature and suggestions for revision of criteria for diagnosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81(6):576–580.

- Milobratovic D, Djordjevic S, Vukicevic J, Bogdanovic Z. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation associated with pregnancy and Hashimoto thyroiditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5):919–921.

- Sanz de Galdeano C, Leaute-Labreze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation: report of five patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13(4):274–277.

- Ebihara T, Nakayama H. Pigmented contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15(4):593–599.

- Osmundsen PE. Pigmented contact dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1970;83(2):296–301.

- Trattner A, Hodak E, David M. Screening patch tests for pigmented contact dermatitis in Israel. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;40(3):155–157.

- Tienthavorn T, Tresukosol P, Sudtikoonaseth P. Patch testing and histopathology in Thai patients with hyperpigmentation due to erythema dyschromicum perstans, lichen planus pigmentosus, and pigmented contact dermatitis. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2014;32(2):185–192.