J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(8):45–48

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(8):45–48

by Smriti Shrestha, MD; Riyaz Shrestha, MBBS; and Manindra Manandhar, MD

Drs. Shrestha, Shrestha and Manandhar are with Dhulikhel Hospital at Kathmandu University in Dhulikhel, Kavrepalanchok, Nepal.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this study.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: We present two cases of lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC) that demonstrated characteristics of half-and-half lacunae or hypopyon sign in dermoscopy. The first case was that of a 19-year-old female patient with localized lymphangioma since childhood, presenting with continuous oozing of blood and fluid from the lesion. The second patient presented with extensive disease with verrucous growths and clear vesicles over the right chest wall. Both patients reported an impact on their quality of life due to constant oozing of the lesions. The magnetic resonance imaging showed depth and extent in localized versus extensive forms of the same condition. A lipectomy was performed on both patients to destroy subcutaneous connecting lymphatics, which caused significant symptomatic improvement in oozing of blood and fluid, which had been present since childhood in both patients. However, we observed a recurrence in the second patient after six months.

Keywords: Circumscriptum, dermoscopy, lipectomy, lymphangioma

Lymphangioma are congenital lymphatic malformations that account for four percent of all vascular tumors and 25 percent of benign vascular growths in children.1 Lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC) is the most common type of lymphangioma of microcystic variant, and is also known as superficial lymphatic malformation (SLM).2,3 Lesions are present at birth or early childhood on axillae, shoulder, upper arm, scrotum, and/or penis or vulva.

Clinically, clusters of translucent vesicles demonstrate a “frog spawn” appearance and appear reddish blue when they contain blood. Frequent lymph discharge, infection, and ulceration are causes of morbidity.3

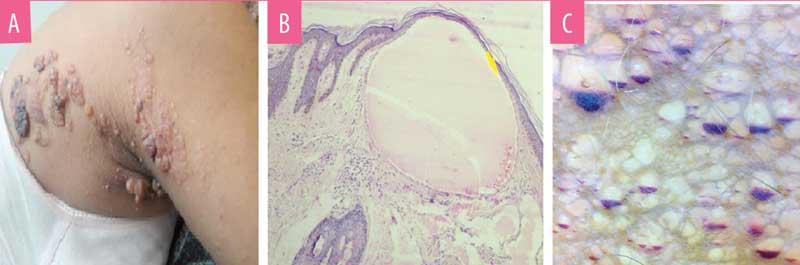

Histology is diagnostic in LC. Normal skin does not have lymphatic channels in the papillary dermis.4 In LC, histology of the vesicle shows epidermal acanthosis and dermal expanded lymphatics lined by endothelial cells visualized as microcysts that might contain erythrocytes and lymphocytes. Dermal lymphatic channels are connected with deeper subcutaneous lymphatic cisterns.3,5

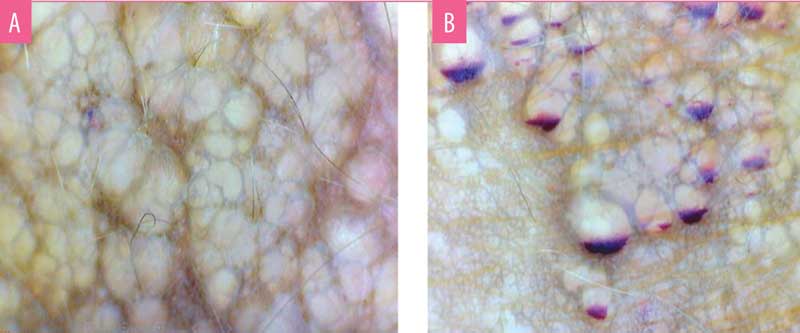

Dermoscopic findings have been shown to aid in the diagnosis of LC. Dermoscopy shows yellow to reddish-blue lacunae with pale septae. The reddish-blue color is due to presence of blood within the lacunae, which might sediment in the bottom, giving a hypopyon-like appearance.6,7

Case Reports

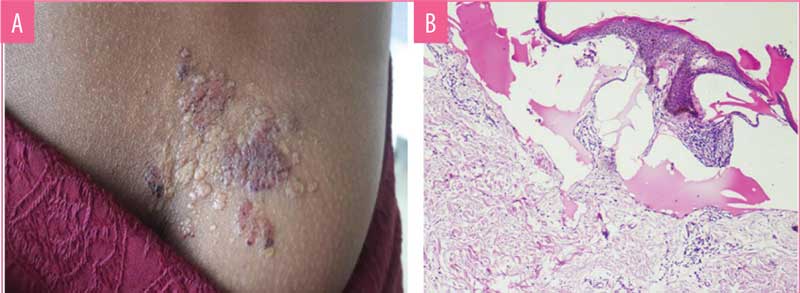

Case 1. A 17-year-old female patient presented with clusters of bluish-red skin and weeping lesions in the para-median aspect of the right lower back (Figure 1a). The patient reported having the lesions since childhood. The lesions grew proportionately with age, with few new vesicles at the periphery. Blood-tinged fluid oozed from the lesion, which constantly stained her undergarments and affected her quality of life. Skin biopsy of the lesion had classical histology (Figure 1b), confirming the diagnosis of localized LC.

Dermoscopy showed two types of findings. Central older lesions showed bluish, distended lacunae with pale septations (Figure 2a). Peripheral reddish-blue lesions showed an accumulation of blood in the lowest part of the lacunae, exhibiting hypopyon-like features, also known as half-and-half lacunae. (Figure 2b)

B) Dermoscopy (Polarised, 25X) of reddish blue lesions showing half-and-half lacunae demonstrating hypopyon-like features

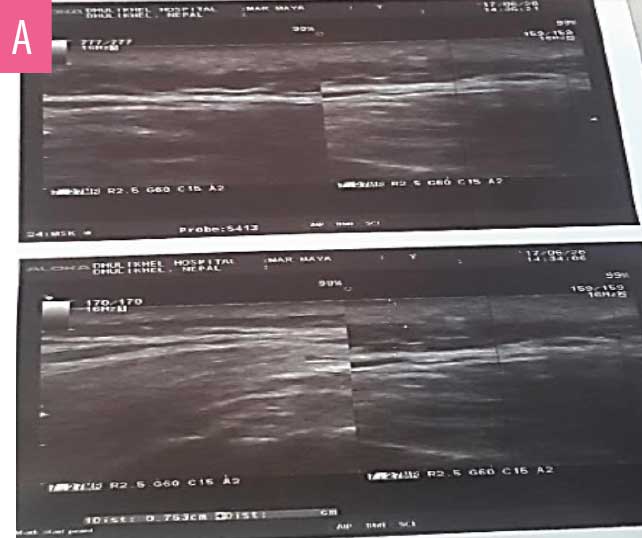

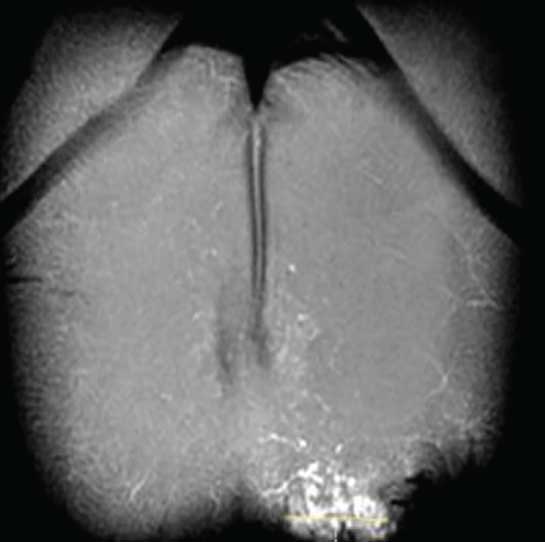

Multiple cystic spaces with septations were noted in dermis and subcutis up to 0.6mm depth (Figure 3a) during the ultrasound (7.5MHz). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to measure the depth more precisely. It showed ill-defined, heterogenous, dilated tubular interconnecting structures across the skin and subcutaneous plane, without extensions into deeper structures (Figures 3b and 3c).

Based on radiological findings, and in consideration of possible aesthetic concerns after treatment, the least disfiguring treatment was chosen. Informed consent was obtained from the patient. Lipectomy was performed under tumescent anesthesia (Figure 4). A 2-mm punch biopsy at the margin of the lesion was used as an adit. Fat destruction along deeper the subcutaneous plane was performed, with manual suction of the subcutaneous tissue. The adit was closed with a non-absorbable suture, which were removed after one week. The patient had no hematoma, bruising, or infection after the procedure. At one year and six months’ follow up, the patient reported no blood or oozing from the lesions.

Case 2. A 20-year-old female patient presented with verrucous skin colored growths over the right upper back that had been present since childhood. She also had discrete, flesh-colored vesicles scattered across the right side of the chest, axilla, and neck, with clear fluid oozing from the lesions (Figure 5a). The patient reported the oozing lesions interfered with her daily activities. Histology confirmed the diagnosis of LC (Figure 5b).

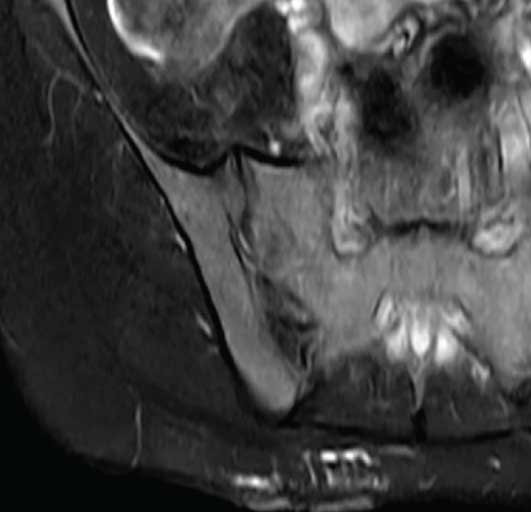

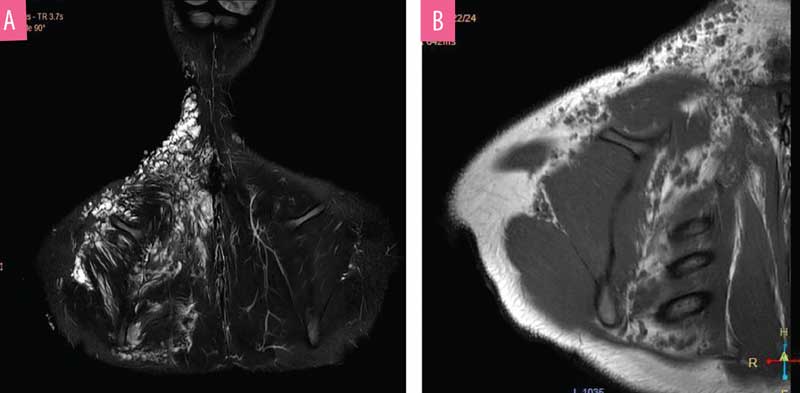

Due to the extensive lesions, an ultrasound was not performed. The MRI showed extensive involvement affecting the right side of the chest wall and involving the muscles and deeper structures (Figures 6a and 6b). The patient had previously visited another dermatology center, prior to visiting us, where ablative CO? laser was performed. However, the lesion recurred; therefore, we chose to perform lipectomy on the verrucous growth of the upper back (Figure 7). Due to cosmetic concerns, ablative CO? laser was performed three weeks after the lipectomy. We observed no oozing during the CO? ablation procedure.

The patient reported no oozing for six months following treatment. However, after this six-month period, there was a recurrence of oozing, which we believe was due to the collateral circulation in extensive lesions. Given the extent and depth, it was not feasible to perform lipectomy over the entire area of the lesions.

Discussion

LC is the most common cutaneous form of lymphangioma.8 In 1970, Peachey et al9 classified LC into two forms: classic and localized. The classical variety of LC is seen soon after birth, and is often larger than 1cm2 in size, while localized LC is smaller and presents later. However, for clinical and treatment purposes, it has been divided into smaller lesions (<7cm) and larger lesions (>7cm).9 Clinically, differential diagnosis of cutaneous LC are other vascular lesions, such as hemangioma, angiokeratoma, warts, molluscum contagiosum, and epidermal nevi.1,2,10

Histology of LC is diagnostic and demonstrates dilated dermal lymphatic channels connected with deeper subcutaneous lymphatic cisterns. According to Whimster’s hypothesis, these subcutaneous muscles coated lymphatic cisterns receive normal lymphatic flow from surrounding tissue but are not drained to normal lymphatic system, and instead drain into superficial dermal lymphatics which project into skin as saccular dilatations. Hence, unless the deep cisterns are excised, superficial lymphatics and skin lesions recur.11

Dermoscopy shows two distinct patterns: yellow lacunae surrounded by pale septa, and reddish-blue lacunae with pale septae.12 The reddish-blue color occurs due to the presence of blood within the lacunae, which might sediment in the bottom in some lacunae, giving the lesions a hypopyon-like appearance. This feature of half-and-half lacunae has been described to differentiate LC from other vascular lesions, such as hemangioma.7,13

MRI helps to determine the depth and extent of involvement of LC, which can be extensive.14,15 MRI aids in preventing incomplete surgical procedures during treatment.16 In our first case, ultrasonography had outlined the depth of the lesion to an extent. Although less specific than MRI, ultrasonography assists in allocating deeper extensions. Given the less expensive modality and ease of availability, ultrasonography can be used as a cost-effective measure in finding deeper connections in cutaneous malformations.

The treatment of choice for LC is surgical excision; however, less invasive methods, such as imiquimod, bleomycin, cryotherapy, sclerotherapy, radiofrequency coagulation, ablative CO? lasers, and suction lipectomy have been used with variable results and recurrences.16 Given the high recurrence rates of available treatment options, lipectomy is the least disfiguring procedure that yields favorable treatment response. Based on Whimster’s hypothesis, the destruction of subcutaneous nidus of lymphatics breaks the connection between dermal lymphatics and the body’s lymphatic system, leading to symptomatic relief and remission.11

Complications of suction lipectomy include contour irregularities, edema, ecchymosis, hematoma, seroma, infection, fat emboli, and pigmentation on overlying skin. Contour irregularity can be avoided by staying strictly in deeper subcutaneous plane during lipectomy. Therefore, lipectomy should only be performed by trained clinicians. Contraindications are uncontrolled hypertension, active infection, use of anticoagulants, and bleeding disorders.17

Conclusion

Considering there was no recurrence reported during the follow-up period in our patient with localized LC, we recommend lipectomy as a treatment option for patients with limited LC of clinically smaller size. In larger lesions, it can also be done prior to ablative laser treatments to prevent oozing of fluid during ablation. However, further studies on more subjects is necessary.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Professor Dr. Shen Gan at Nanjing Medical University in China for teaching me the art of liposuction and lipectomy.

References

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290–1295.

- James WD, Burger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases the Skin Clinical Dermatology, 10th edition. United Kingdom: Saunders Elsevier;2011:579–582.

- Mortimer PS. Disorders of lymphatic vessels. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C (eds). Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology, Seventh edition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2004:51.23.

- Kokcam I. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the penis: a case report. Acta Dermatovenrol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2007;16:81–82.

- Kudur MH, Hulmani M. Extensive and invasive lymphangioma circumscriptum in a young female: a rare case report and review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4(3):199–201.

- Massa AF, Menezes N, Baptista A, Moreira AI, Ferreira EO. Cutaneous Lymphangioma circumscriptum – dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(2):262–264.

- Gencoglan G, Inanir I, Ermertcan AT. Hypopyon-like features: new dermoscopic criteria in the differential diagnosis of cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum and haemangiomas?. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1023–1025.

- Heller M, Mengden S. Lymphangioma circumscriptum. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14(5):27.

- Peachey RD, Lim CC, Whimster IW. Lymphangioma of skin. A review of 65 cases. Br J Dermatol. Nov 1970;83(5):519-27.

- Kim JH, Nam TS, Kim SH. Solitary angiokeratoma developed in one area of lymphangioma circumscriptum. J Korean Med Sci. 1988;3:169–170.

- Whimster I. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:473–86

- Scope A, Amini S, Kim NH, et al. Dermoscopic-histopathologic correlation of cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(12):1671–1672.

- Jha AK, Lallas A, Sonthalia S. Dermoscopy of cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7(2):37–38.

- McAlvany JP, Jorizzo JL, Zanolli D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129(2):194–197.

- Kudur MH, Hulmani M. Extensive and invasive lymphangioma circumscriptum in a young female: a rare case report and review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4(3):199–201.

- Puri N. Treatment options of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(4): 293–294.

- Gargan TJ, Courtiss EH.The risks of suction lipectomy. Their prevention and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1984;11(3):457-63.