J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(7):30–32.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(7):30–32.

by Aaron M. Secrest, MD, PhD; Garrett C. Coman, MD, MS; J. Michael Swink, BS; and Keith L. Duffy, MD

Drs. Secrest, Coman, and Duffy are with the Department of Dermatology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Dr. Secrest is also with the Department of Population Health Sciences at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. Mr. Swink is with the School of Medicine at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah.

FUNDING: Dr. Secrest receives support from a Dermatology Foundation Public Health Career Development Award as well as research grant support from the American Skin Association, National Eczema Association, National Psoriasis Foundation. However, the views expressed herein are his own and do not represent the views of these organizations.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: With a 34-percent increase in dermatology residency applications in the past decade, residency programs are increasingly faced with the daunting task of reviewing more applications for a relatively fixed number of residency positions. Other specialty programs, including otolaryngology, orthopedics, plastic surgery, and ophthalmology, have called for limiting the number of residency applications. Dermatology programs have developed various ways to decrease the number of reviewed applications, from cutoffs for Step 1 board scores to Alpha Omega Alpha membership to secondary applications. While this can decrease the applicant pool, it limits a more holistic review of applications. We propose an application cap of 20 programs, which will decrease the number of applications each program receives 3- to 5-fold. Each applicant can approach the process more thoughtfully in choosing the best programs for them and will save money in application fees. As program directors rank “perceived interest” in their residency program as a primary factor for selecting applicants, a cap will allow program directors to know that all applicants are interested in their specific program. Ultimately, we contend that application caps would improve match outcomes with applicants receiving training in the best program for them, increasing the likelihood of successful fit for clinical training, opening the field to a more diverse set of applicants, and saving everyone time and money.

Keywords: Dermatology, residency applications, selection process, ERAS, NRMP, game theory, Step 1 exam, COVID, equity

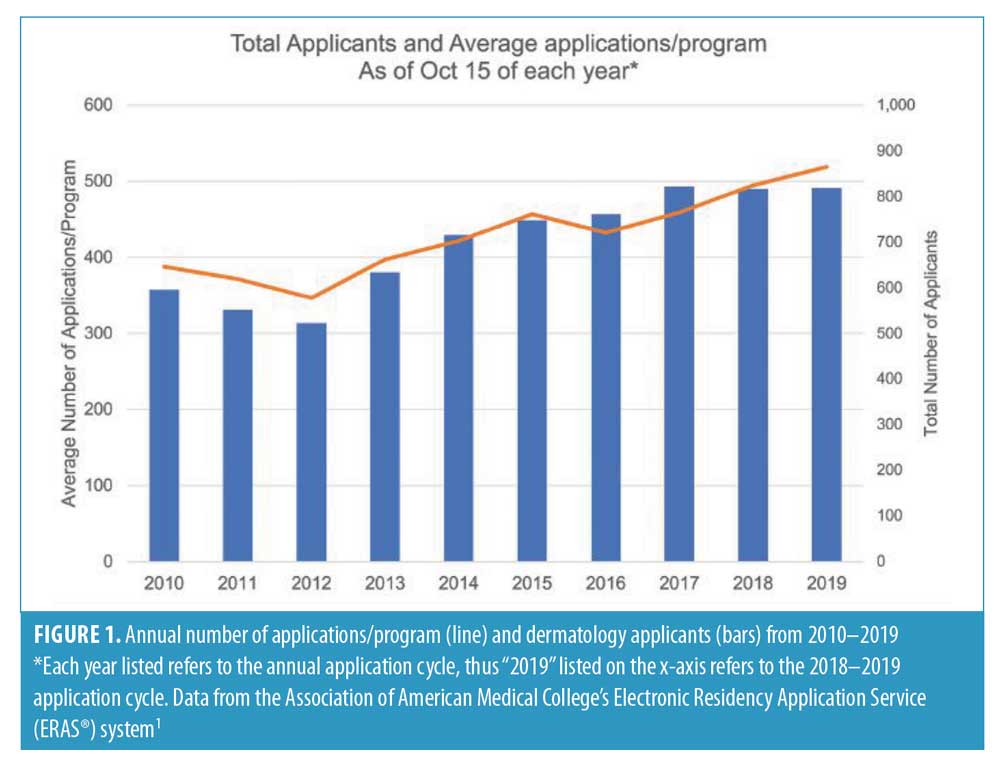

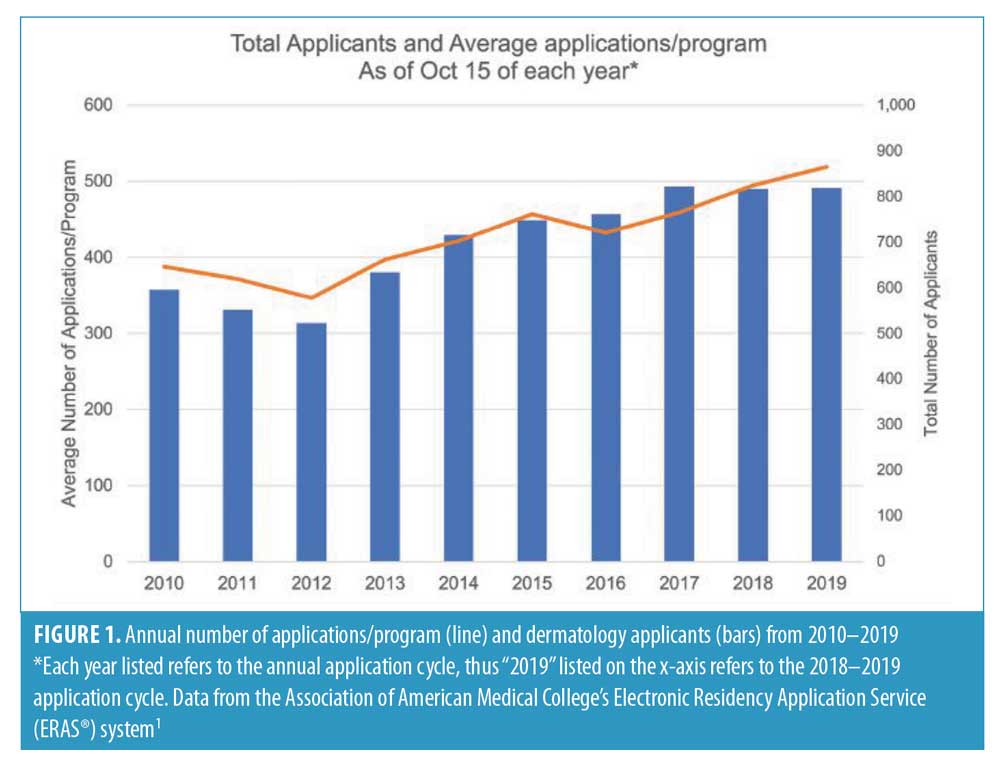

Dermatology residency applications have increased 33.9 percent over the past decade to a limited number of United States (US) dermatology residency positions (Figure 1). US dermatology programs now receive 492 applications on average. The typical US dermatology applicant now applies to 77.0 programs, up from 64.8 a decade ago, and this trend negatively impacts the match process in dermatology.1

Current System

For years, the supply of dermatology residency spots has not met the ever-increasing demand of applications. Program directors, mentors, current residents, and peers also encourage dermatology applicants to apply broadly—sometimes to every dermatology program—with the aim of securing as many interviews as possible. This strategy likely originates from inappropriately extrapolating that more applications yields higher match success from data showing that the more programs an applicant ranks, the more likely they are to match successfully.2

This perception and incentive structure have led to residency programs receiving an overwhelming number of applications. In 2020, our program at the Department of Dermatology at the University of Utah received 568 applications. We interviewed 32 applicants for four residency positions (success rate=0.70%), four times lower than the acceptance rate into the most competitive US medical schools.3

Consequences for Dermatology Applicants

Dermatology applicants hope that residency programs assess every applicants’ strengths and weaknesses in a thorough and balanced manner. However, few programs thoroughly review each submitted application due to application volume and time constraints. Dermatology programs have developed various means to decrease the number of reviewed applications to a more pragmatic number, from cutoffs for Step 1 board scores (usually 230 or more or 240 or more) or other academic variables to Alpha Omega Alpha membership. While this decreases the applicant pool, some of our program’s hardest-working and most successful residents had Step 1 scores lower than the arbitrary cutoffs imposed at many programs. Also, with Step 1 scheduled to become pass/fail in 2022, this screening tool will soon be unavailable to residency programs.4

To discourage applicants lacking particular interest in a program, programs can require a secondary application. However, nearly all applicants complete secondary applications, thus increasing the content for review without decreasing the applicant pool. One program’s secondary application required reading a 200-page book on personal strengths and writing how these strengths will lead to success at that program. Another program only extended interviews to rotators or in-state medical school graduates. Most attempts to limit applications are unsuccessful because the opportunity costs are not high enough to dissuade applicants.

Consequences for Dermatology Residency Programs

The two most important factors cited by dermatology program directors for selecting future residents are: 1) personal prior knowledge of the applicant and 2) “away” rotation within your department, with “perceived interest in program” being far less important.2 Rationally, applicants’ perceived interest would be highly relevant in identifying those who are a “good fit.” However, when applicants apply to an average of 77 programs and express interest at every interview, program directors struggle with determining true interest.

Hundreds of hours would be needed to thoroughly review roughly 500 applications. We argue this time could be better spent training residents and medical students, providing high-quality patient care, and performing research. Programs currently interview 8 to 12 applicants for every residency position and these additional interview dates, meals, and lost clinical revenue and protected academic time are costly. Fewer applications, and thus, the need for fewer interviews would save programs time and money and increase the proportionate faculty time spent on individual applications.

Benefits for ERAS® and National Resident Match Program (NRMP®)

An applicant applying to 77 programs pays $1,641 ($99 for first 10 programs + $14 each for 11–20 programs + $18 each for 21–30 programs + $26 each for 31+ programs).5 Thus, ERAS received approximately $1.42 million this year in fees from dermatology residency applications alone. NRMP charges an additional $85 to rank up to 20 dermatology programs.

Proposed Change

We contend that both applicants and dermatology residency programs will benefit from capping dermatology applications at 20 programs per applicant. This is higher than the number of medical schools (16) to which the average undergraduate student applies.6

Dr. Lloyd Shapley’s Nobel Prize-winning work on matching theory—originally applied to marriage proposals—provided the basis for the NRMP Match algorithm. This deferred acceptance algorithm suspends a final match until all rankings have been assessed, ensuring that no one else had a higher claim to a spot at a given program, even if those students ranked the school lower on their preference list. Our proposed change addresses another aspect of Dr. Shapley’s work—game theory: if all applicants agree to apply to only 20 programs, everyone benefits. However, if anyone secretly cheats and applies to more than 20 programs, they would benefit and other applicants would suffer (a real-life example of the famous “Prisoner’s Dilemma”).7 Therefore, the 20-application limit must be a hard limit through ERAS.

Benefits for Dermatology Applicants

An application cap will allow applicants to be more thoughtful and invested in the specific programs to which they apply. They can more thoroughly evaluate each program and individualize their Personal Statements to identify how each program’s strengths would fit the applicant’s specific needs and how the applicant can contribute to the program. This limit would also eliminate adverse interest signaling, as program directors would know that applicants are truly invested in their programs. The average dermatology applicant would save about $1,400 in application fees alone (applying to 20 programs would cost $239).5 In addition, applicants would save thousands of dollars by not doing extra interviews—each interview can cost over $500 in travel and lodging. Additionally, medical students can spend limited fourth-year time honing clinical skills or pursuing research interests rather than traveling the country doing extra interviews.

Benefits for Dermatology Residency Programs

Dermatology programs, receiving a more manageable number of applications (~100–125 applications/program), will be more likely to devote sufficient time to appropriately review and consider each applicant without the need for arbitrary screening. Also, programs will already know the applicant’s “perceived interest,” because a cap requires each applicant to pre-select their top 20 programs. Programs can discard onerous secondary applications by having applicants individualize their 20 Personal Statements.

Current application strategies encourage students to apply to as many programs as possible to increase their odds of acceptance. Under the proposed system, students would be encouraged to be more thoughtful and circumspect in applying to programs that fit them best to maximize their chance of acceptance. Data are lacking on how such a limit might affect specific dermatology residency programs, but medical students report that practical barriers (i.e., academic scores, family/personal preferences, and finances) do affect their selection of specialty,8,9 revealing that students self-select based on goodness of fit and suggesting that all dermatology programs will benefit, not just the most selective programs.

Consequences for ERAS® and NRMP®

ERAS would suffer a roughly $1.21 million loss in annual fees from a dermatology application cap. However, ERAS is a not-for-profit organization created to serve the needs of medical students, and as dermatology represents less than two percent of total residency applications, this revenue loss should not impact their ability to serve medical students. ERAS already encourages fewer applications, with higher fees for increasing number of applications. NRMP’s $85 fee already allows ranking up to 20 programs.5

Consequences of the Current Pandemic

COVID-19 has drastically altered how residency programs and applicants interact,10 from fewer away rotations to virtual interviews. Thus, programs and students will have even less of an opportunity to gauge fit and show honest interest in future investment. Conversely, COVID-19 has helped level the playing field financially by converting to virtual residency interviews, thereby saving applicants significant travel costs, which make up the majority of the cost of applying to residency. Dermatology programs will need to maintain accurate, up-to-date information online to help potential applicants understand their values and strengths and assess goodness of fit. While some of the COVID-related changes are burdensome, we hope that those leveling the playing field for applicants can continue.

Conclusion

Dermatology’s application problem is not unique—other specialties have called for limiting applications to benefit both applicants and programs.11–13 Concern exists that caps would limit geographic diversity; however, we contend that the current system already limits geographic diversity (program directors’ two most important factors relate to familiarity with the applicant). Limiting residency applications has not been trialed, so predicting how applicants and programs will respond is difficult. We contend that a thorough review of applications will promote more incoming residents with a diverse life experience who are not simply defined and driven by attaining exceptional scores on standardized tests. We hope this encourages geographic migration, as applicants’ interest in programs will be implied as being in their top 20. Ultimately, application caps would improve match outcomes with applicants receiving training in the best program for them, increasing the likelihood of success in clinical training, opening the field to a more diverse set of applicants, and saving everyone time and money.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the critical review of an early manuscript by Sarah Cipriano, MD, MPH, MS.

References

- Historic Specialty Specific Data. 2019; https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/stats/ 359278/stats.html. Accessed April 30, 2021.

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee: Results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. National Resident Matching Program. Washington, DC. 2018.

- Moody J. 10 Medical Schools With the Lowest Acceptance Rates. https://www.usnews. com/education/best-graduate-schools/the-short-list-grad-school/articles/medical-schools-with-the-lowest-acceptance-rates. Accessed April 30, 2021.

- Rozenshtein A, Mullins ME, Marx MV. The USMLE Step 1 Pass/Fail Reporting Proposal: The APDR Position. Acad Radiol. 2019;26(10): 1400–1402.

- Fees for ERAS Residency Applications. 2020; https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-residency/article/fees-eras-residency-applications. Accessed April 30, 2021.

- American Association of Medical Colleges. Table A-1: U.S. Medical School Applications and Matriculants by School, State of Legal Residence, and Sex, 2020-2021. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-10/2020_FACTS_Table_A-1.pdf. Accessed April 30, 2021.

- Molina Burbano F, Yao A, Burish N, et al. Solving congestion in the plastic surgery match: A game theory analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(2):634-639.

- Nieman LZ, Holbert D, Bremer CC, Nieman LJ Specialty career decision making of third-year medical students. Fam Med. 1989; 21359–21363.

- Martorin A, Venegas-Samuels K, Ruiz P, Butler P, Abdulla A. (2000). U.S. medical students’ choice of careers and its future impact on health care manpower. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2000; 22(4);495–509.

- Kearns DG, Chat VS, Uppal S, Wu JJ. Applying to dermatology residency during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1214–1215.

- Naclerio RM, Pinto JM, Baroody FM. Drowning in applications for residency training: a program’s perspective and simple solutions. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(8): 695–696.

- Kraeutler MJ. It Is time to change the status quo: limiting orthopedic surgery residency applications. Orthopedics. 2017;40(5): 267–268.

- Deng F, Chen JX, Wesevich A. More transparency is needed to curb excessive residency applications. Acad Med. 2017;92(7): 895–896.

Limiting Residency Applications to Dermatology Benefits Nearly Everyone

Categories:

by Aaron M. Secrest, MD, PhD; Garrett C. Coman, MD, MS; J. Michael Swink, BS; and Keith L. Duffy, MD

Drs. Secrest, Coman, and Duffy are with the Department of Dermatology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Dr. Secrest is also with the Department of Population Health Sciences at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. Mr. Swink is with the School of Medicine at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah.

FUNDING: Dr. Secrest receives support from a Dermatology Foundation Public Health Career Development Award as well as research grant support from the American Skin Association, National Eczema Association, National Psoriasis Foundation. However, the views expressed herein are his own and do not represent the views of these organizations.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: With a 34-percent increase in dermatology residency applications in the past decade, residency programs are increasingly faced with the daunting task of reviewing more applications for a relatively fixed number of residency positions. Other specialty programs, including otolaryngology, orthopedics, plastic surgery, and ophthalmology, have called for limiting the number of residency applications. Dermatology programs have developed various ways to decrease the number of reviewed applications, from cutoffs for Step 1 board scores to Alpha Omega Alpha membership to secondary applications. While this can decrease the applicant pool, it limits a more holistic review of applications. We propose an application cap of 20 programs, which will decrease the number of applications each program receives 3- to 5-fold. Each applicant can approach the process more thoughtfully in choosing the best programs for them and will save money in application fees. As program directors rank “perceived interest” in their residency program as a primary factor for selecting applicants, a cap will allow program directors to know that all applicants are interested in their specific program. Ultimately, we contend that application caps would improve match outcomes with applicants receiving training in the best program for them, increasing the likelihood of successful fit for clinical training, opening the field to a more diverse set of applicants, and saving everyone time and money.

Keywords: Dermatology, residency applications, selection process, ERAS, NRMP, game theory, Step 1 exam, COVID, equity

Dermatology residency applications have increased 33.9 percent over the past decade to a limited number of United States (US) dermatology residency positions (Figure 1). US dermatology programs now receive 492 applications on average. The typical US dermatology applicant now applies to 77.0 programs, up from 64.8 a decade ago, and this trend negatively impacts the match process in dermatology.1

Current System

For years, the supply of dermatology residency spots has not met the ever-increasing demand of applications. Program directors, mentors, current residents, and peers also encourage dermatology applicants to apply broadly—sometimes to every dermatology program—with the aim of securing as many interviews as possible. This strategy likely originates from inappropriately extrapolating that more applications yields higher match success from data showing that the more programs an applicant ranks, the more likely they are to match successfully.2

This perception and incentive structure have led to residency programs receiving an overwhelming number of applications. In 2020, our program at the Department of Dermatology at the University of Utah received 568 applications. We interviewed 32 applicants for four residency positions (success rate=0.70%), four times lower than the acceptance rate into the most competitive US medical schools.3

Consequences for Dermatology Applicants

Dermatology applicants hope that residency programs assess every applicants’ strengths and weaknesses in a thorough and balanced manner. However, few programs thoroughly review each submitted application due to application volume and time constraints. Dermatology programs have developed various means to decrease the number of reviewed applications to a more pragmatic number, from cutoffs for Step 1 board scores (usually 230 or more or 240 or more) or other academic variables to Alpha Omega Alpha membership. While this decreases the applicant pool, some of our program’s hardest-working and most successful residents had Step 1 scores lower than the arbitrary cutoffs imposed at many programs. Also, with Step 1 scheduled to become pass/fail in 2022, this screening tool will soon be unavailable to residency programs.4

To discourage applicants lacking particular interest in a program, programs can require a secondary application. However, nearly all applicants complete secondary applications, thus increasing the content for review without decreasing the applicant pool. One program’s secondary application required reading a 200-page book on personal strengths and writing how these strengths will lead to success at that program. Another program only extended interviews to rotators or in-state medical school graduates. Most attempts to limit applications are unsuccessful because the opportunity costs are not high enough to dissuade applicants.

Consequences for Dermatology Residency Programs

The two most important factors cited by dermatology program directors for selecting future residents are: 1) personal prior knowledge of the applicant and 2) “away” rotation within your department, with “perceived interest in program” being far less important.2 Rationally, applicants’ perceived interest would be highly relevant in identifying those who are a “good fit.” However, when applicants apply to an average of 77 programs and express interest at every interview, program directors struggle with determining true interest.

Hundreds of hours would be needed to thoroughly review roughly 500 applications. We argue this time could be better spent training residents and medical students, providing high-quality patient care, and performing research. Programs currently interview 8 to 12 applicants for every residency position and these additional interview dates, meals, and lost clinical revenue and protected academic time are costly. Fewer applications, and thus, the need for fewer interviews would save programs time and money and increase the proportionate faculty time spent on individual applications.

Benefits for ERAS® and National Resident Match Program (NRMP®)

An applicant applying to 77 programs pays $1,641 ($99 for first 10 programs + $14 each for 11–20 programs + $18 each for 21–30 programs + $26 each for 31+ programs).5 Thus, ERAS received approximately $1.42 million this year in fees from dermatology residency applications alone. NRMP charges an additional $85 to rank up to 20 dermatology programs.

Proposed Change

We contend that both applicants and dermatology residency programs will benefit from capping dermatology applications at 20 programs per applicant. This is higher than the number of medical schools (16) to which the average undergraduate student applies.6

Dr. Lloyd Shapley’s Nobel Prize-winning work on matching theory—originally applied to marriage proposals—provided the basis for the NRMP Match algorithm. This deferred acceptance algorithm suspends a final match until all rankings have been assessed, ensuring that no one else had a higher claim to a spot at a given program, even if those students ranked the school lower on their preference list. Our proposed change addresses another aspect of Dr. Shapley’s work—game theory: if all applicants agree to apply to only 20 programs, everyone benefits. However, if anyone secretly cheats and applies to more than 20 programs, they would benefit and other applicants would suffer (a real-life example of the famous “Prisoner’s Dilemma”).7 Therefore, the 20-application limit must be a hard limit through ERAS.

Benefits for Dermatology Applicants

An application cap will allow applicants to be more thoughtful and invested in the specific programs to which they apply. They can more thoroughly evaluate each program and individualize their Personal Statements to identify how each program’s strengths would fit the applicant’s specific needs and how the applicant can contribute to the program. This limit would also eliminate adverse interest signaling, as program directors would know that applicants are truly invested in their programs. The average dermatology applicant would save about $1,400 in application fees alone (applying to 20 programs would cost $239).5 In addition, applicants would save thousands of dollars by not doing extra interviews—each interview can cost over $500 in travel and lodging. Additionally, medical students can spend limited fourth-year time honing clinical skills or pursuing research interests rather than traveling the country doing extra interviews.

Benefits for Dermatology Residency Programs

Dermatology programs, receiving a more manageable number of applications (~100–125 applications/program), will be more likely to devote sufficient time to appropriately review and consider each applicant without the need for arbitrary screening. Also, programs will already know the applicant’s “perceived interest,” because a cap requires each applicant to pre-select their top 20 programs. Programs can discard onerous secondary applications by having applicants individualize their 20 Personal Statements.

Current application strategies encourage students to apply to as many programs as possible to increase their odds of acceptance. Under the proposed system, students would be encouraged to be more thoughtful and circumspect in applying to programs that fit them best to maximize their chance of acceptance. Data are lacking on how such a limit might affect specific dermatology residency programs, but medical students report that practical barriers (i.e., academic scores, family/personal preferences, and finances) do affect their selection of specialty,8,9 revealing that students self-select based on goodness of fit and suggesting that all dermatology programs will benefit, not just the most selective programs.

Consequences for ERAS® and NRMP®

ERAS would suffer a roughly $1.21 million loss in annual fees from a dermatology application cap. However, ERAS is a not-for-profit organization created to serve the needs of medical students, and as dermatology represents less than two percent of total residency applications, this revenue loss should not impact their ability to serve medical students. ERAS already encourages fewer applications, with higher fees for increasing number of applications. NRMP’s $85 fee already allows ranking up to 20 programs.5

Consequences of the Current Pandemic

COVID-19 has drastically altered how residency programs and applicants interact,10 from fewer away rotations to virtual interviews. Thus, programs and students will have even less of an opportunity to gauge fit and show honest interest in future investment. Conversely, COVID-19 has helped level the playing field financially by converting to virtual residency interviews, thereby saving applicants significant travel costs, which make up the majority of the cost of applying to residency. Dermatology programs will need to maintain accurate, up-to-date information online to help potential applicants understand their values and strengths and assess goodness of fit. While some of the COVID-related changes are burdensome, we hope that those leveling the playing field for applicants can continue.

Conclusion

Dermatology’s application problem is not unique—other specialties have called for limiting applications to benefit both applicants and programs.11–13 Concern exists that caps would limit geographic diversity; however, we contend that the current system already limits geographic diversity (program directors’ two most important factors relate to familiarity with the applicant). Limiting residency applications has not been trialed, so predicting how applicants and programs will respond is difficult. We contend that a thorough review of applications will promote more incoming residents with a diverse life experience who are not simply defined and driven by attaining exceptional scores on standardized tests. We hope this encourages geographic migration, as applicants’ interest in programs will be implied as being in their top 20. Ultimately, application caps would improve match outcomes with applicants receiving training in the best program for them, increasing the likelihood of success in clinical training, opening the field to a more diverse set of applicants, and saving everyone time and money.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the critical review of an early manuscript by Sarah Cipriano, MD, MPH, MS.

References

Share:

Recent Articles:

Categories:

Recent Articles:

Tags: