J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(7):34–37.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(7):34–37.

by Saurabh Sharma, MD, DNB, MNAMS; Jasleen Kaur, MD; Roopam Bassi, MD; and Harkanwal Kaur Sekhon, MD

Drs. Sharma, Kaur, and Sekhon are with the Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprosy at Sri Guru Ram Das Institute of Medical Sciences and Research in Amritsar, Punjab, India. Dr. Bassi is with the Department of Physiology at Sri Guru Ram Das Institute of Medical Sciences and Research in Amritsar, Punjab, India.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Lichen planus is an immune-mediated disorder affecting the skin, mucous membranes, scalp, and nails.

Objective. We sought to evaluate dermatoscopic nail patterns in patients with lichen planus.

Methods. This was a cross-sectional, observational study performed in the outpatient dermatology department of a tertiary care hospital. Thirty-one patients with skin biopsy-proven lichen planus with nail changes were included. An evaluation of clinical nail patterns and dermoscopic assessment of nail patterns were performed.

Results. Longitudinal ridging with splitting, longitudinal melanonychia and splinter hemorrhages were the most commonly found nail patterns in patients with lichen planus. Pterygium has been found to be most pathognomic feature of nail lichen planus.

Conclusion. Dermatoscopy has been demonstrated to be a valuable, noninvasive tool to identify subsurface nail bed changes and subclinical surface findings to facilitate early diagnosis and timely management of lichen planus to avoid long-term sequelae.

Keywords: Lichen planus, dermoscopy, nail

Lichen planus (LP) is an immune-mediated disorder affecting skin, mucous membranes, scalp, and nails.1 Clinically, LP is a chronic dermatosis characterized by plain, small, flat-topped, pruritic, shiny, polygonal violaceous papules that may coalesce into plaques.2 Prevalence rates of LP vary in the literature, ranging from 0.5 to 1 percent of the population.3 Nail involvement affects approximately 10 percent of patients with LP, and 25 percent of patients with nail LP have involvement of other sites occurring either before or after the involvement of nails.4 Nail LP mainly affects men, and involvement of the fingernails is much more common than the toenails.4 The morphological features of nail involvement vary according to the part of nail unit involved.5 Involvement of the nail matrix leads to nail plate thinning, longitudinal ridging, and pterygium, whereas nail bed involvement presents as onycholysis, pup-tent sign, and longitudinal melanonychia.3 The disease can progress to total nail dystrophy and anonychia in most cases, so early diagnosis and treatment decision-making is of paramount importance in LP. The histopathological analysis of nails is the gold standard in the diagnosis of LP, but difficulties in achieving histopathological analysis (in relation to biopsy technique), sample analysis, and patient willingness to undergo biopsy have led to delays in diagnosis.6 Dermatoscopy is a useful noninvasive tool that can aid in the diagnosis of nail conditions.7 We carried out the present study to evaluate the role of dermatoscopy in nail LP and to determine if dermatoscopy can better evaluate the clinical presentation of disease, which would aid in the confirmation of diagnosis, assessment of prognosis, and optimizing treatment decisions.

Methods

The present descriptive and observational study included 31 patients with skin biopsy-proven LP selected using STROBE randomization during the period of January 2018 to September 2019.8 Approval from our institutional ethics committee was obtained beforehand. Informed consent was collected from each patient. All skin biopsy-proven cases of LP with clinically appreciable nail changes in the age group of 18 to 70 years were enrolled in the study. Nail biopsy was performed in nine cases, as their skin biopsy results were inconclusive. A detailed demographic history was collected from each patient. Local skin and nail clinical examinations were performed to elucidate the morphology of nail patterns, followed by dermatoscopic examination of all nails to discern morphological changes in nail patterns and capillary examination to examine all 20 nails on each patient. The DL4 dermatoscope (DermLite, San Juan Capistrano, California) with polarized mode and a magnification of 10× was used for both wet and dry dermatoscopy. The nonpolarized mode was used for nail plate examination to identify nail plate surface changes. In six patients, Giemsa staining was used to stain the edges of the pits. The polarized mode was used for nail bed examination and color changes. The linkage fluid used was gel-based hand sanitizer. All nails were examined in a sequence of dermatoscopic examination of the proximal nail folds, lateral nail folds, lunula, nail plate surface changes, and nail bed changes. Photographs of findings were taken and recorded. The results were analyzed statistically using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19.0 software program (IBM Corporationo, Armonk, New York). The chi-squared test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and one-way analysis of variance were used for comparing different variables and establishing correlations.

Results

Among the 31 participants, 23 were women and eight were men. The mean age of the patients was 45.48 years (standard deviation: 14.2 years) and the mean duration of illness was 5.32 years, with a standard deviation of 2.3 years. In total, 54 percent (n=16) of the patients had been suffering from skin lesions for over five years.

Nail fold lesions in the form of violaceous papules were seen in 6.4 percent (n=2) of patients, ragged cuticles were found in 38.7 percent (n=12) of patients, and paronychia was observed in 19.3 percent (n=6) of patients. The nail plate was thinned in 64.5 percent (n=20) of patients and fragmented in 35.4 percent (n=11) of patients.

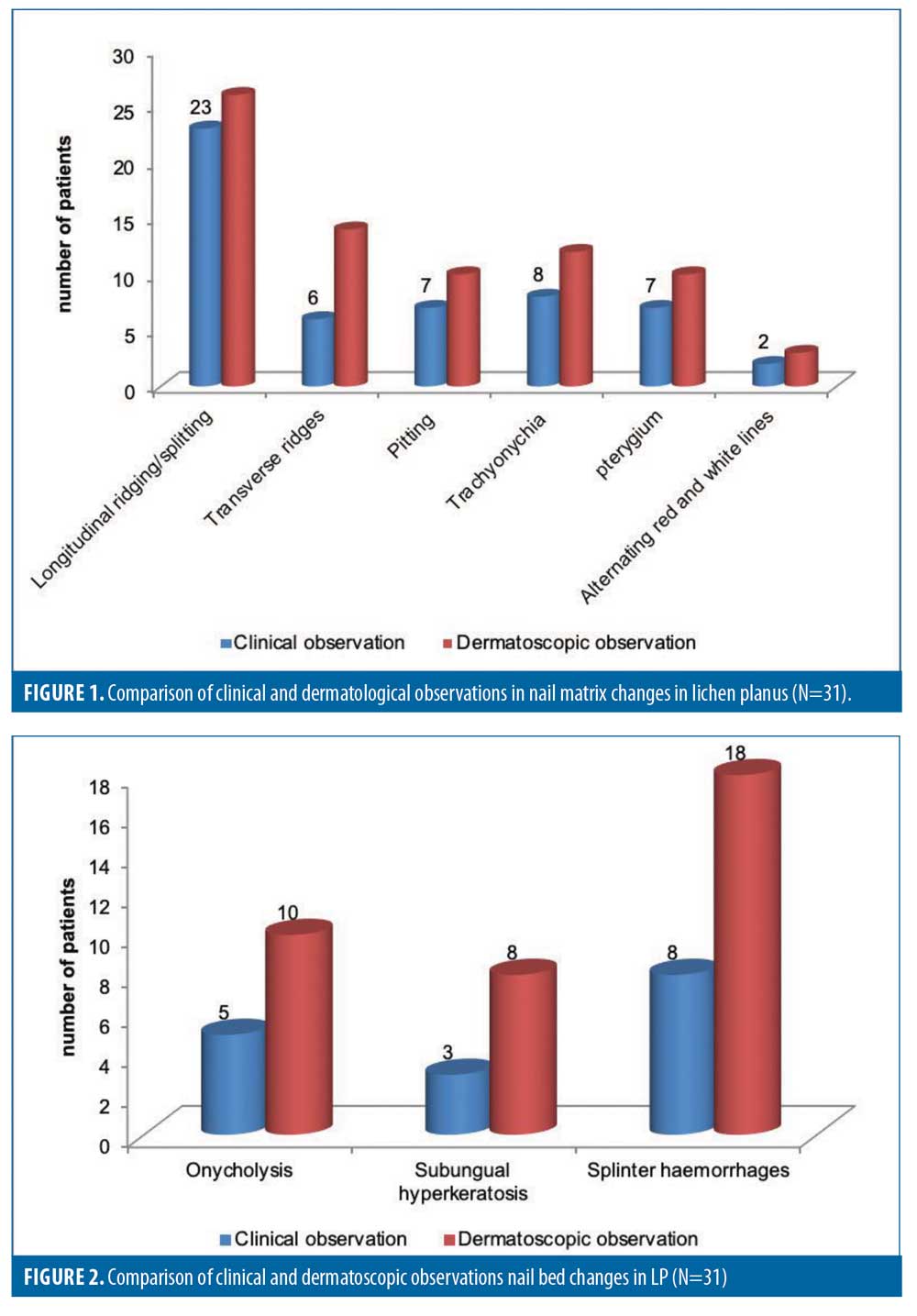

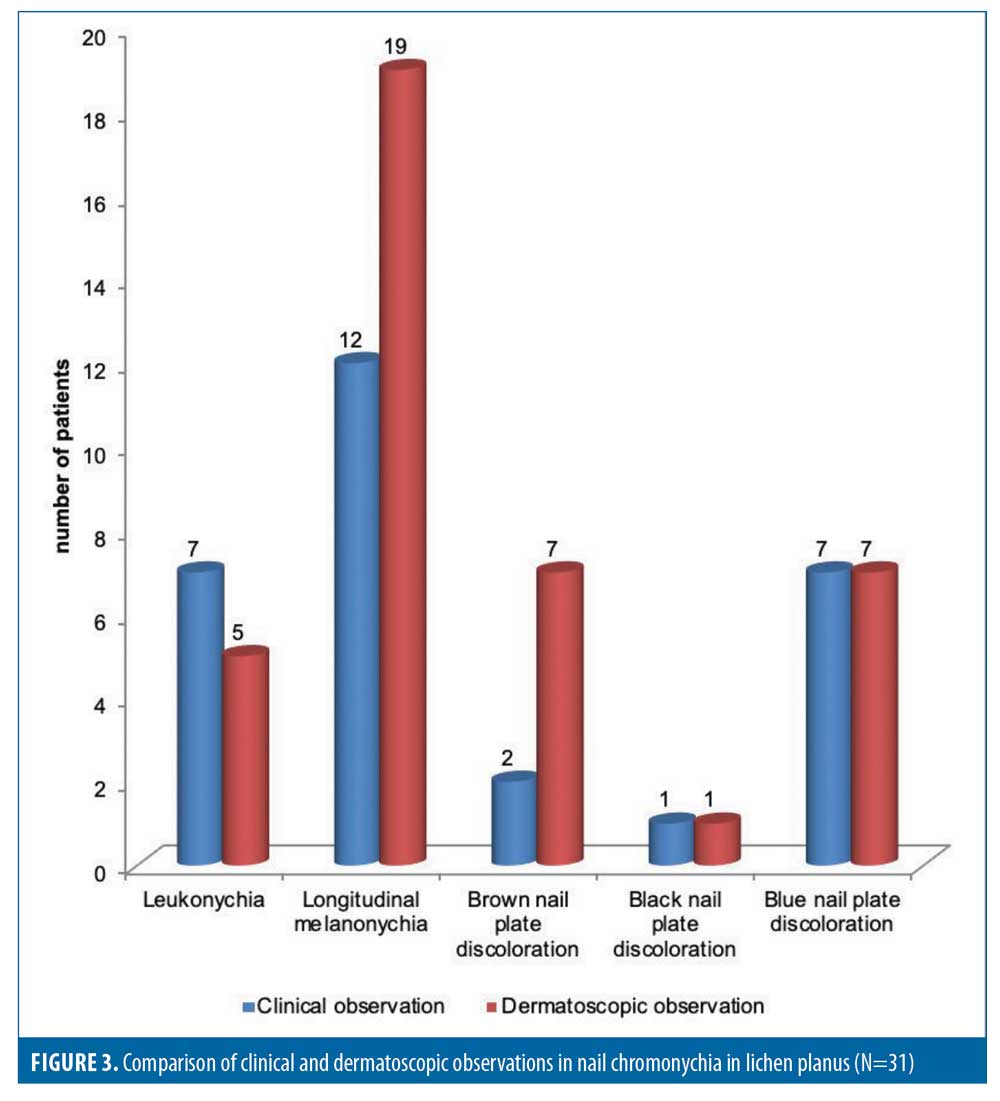

The nail matrix changes observed in these patients included longitudinal ridges/splitting, transverse ridges, pitting, trachyonychia, and pterygium (Figure 1). Nail bed changes observed after wet examination included onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhage (Figure 2). The nails affected by LP also showed chromonychial changes in the form of leuconychia, longitudinal melanonychia, and nail plate discoloration (Figure 3). These patterns were first observed clinically, then by dermatoscopy, and the two observations were compared.

Discussion

Not many studies conducting dermatoscopy of nail LP have been performed. Nail dermatoscopic characteristics have been described in only three studies to date and there have been no attempts to correlate them with clinical features.5,9,10

In our study, more female patients than male patients presented with the disease. The most common nail feature found was nail matrix involvement in the form of longitudinal ridges in 74.2 percent of patients clinically and in 83.9 percent of patients dermatoscopically. The second most common feature was longitudinal melanonychia, seen in 61.3 percent of cases, followed by splinter hemorrhage in 58.1 percent of cases dermatoscopically. Regarding nail matrix changes, trachyonychia was seen in 25.8 percent of patients clinically and in 38.7 percent of patients dermatoscopically. Nail pitting was seen in 22.45 percent of cases clinically and 32.3 percent dermatoscopically. Pterygium was seen in 22.6 percent of patients clinically and in 32.3 percent of patients dermatoscopically. Pterygium in nail LP is an uncommon occurrence but, when seen, it is a pathognomic sign of LP nearly never found in any other papulosquomous disorders, thus establishing a sure diagnosis of LP.10 Transverse ridging was also seen in 19.4 percent of patients clinically and in 45.2 percent of patients dermatoscopically. Nakamura et al10 previously described onychoscopic features in 11 patients with 79 affected nails and divided them into nail matrix and nail bed changes. Nail matrix changes reported in their study included trachyonychia (40.5%), pitting (34.2%), and pterygium (21.5%), consistent with the rates of our study except that for pterygium, which was slightly higher.10 In the study conducted by Bhatt et al,11 nail matrix changes described were pitting in 44.44 percent of patients and pterygium in 33.33 percent of patients, consistent with our results.11 Differences in clinical and dermatoscopic observations regarding all nail surface changes were nonsignificant.

Nail bed changes observed in our study included onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhage. Observing these nail patterns clinically and dermatoscopically, onycholysis was seen in 16.1 percent and 32.3 percent of patients, respectively, while subungual hyperkeratosis was present in 9.7 percent and 16.1 percent of patients, respectively. The difference in observations was significant. Puri et al12 described clinically observed onycholysis in 16 percent of patients and subungual hyperkeratosis in 12 percent of patients, which are lower rates than in our study.12 In another clinical study by David et al,13 subungual hyperkeratosis was reported in 25 percent of patients, onycholysis was found in 75 percent of patients, and longitudinal melanonychia was present in 50 percent of patients, which are higher rates than in our study.13 Nakamura et al10 dermatoscopically described onycholysis in 27.8 percent of patients and subungual hyperkeratosis in 7.59 percent of patients, which are rates that are almost similar to ours.10 Bhat et al11 described similar changes in their study, with onycholysis observed in 33.33 percent of patients and subungual hyperkeratosis observed in 22.22 percent of patients. In our study, splinter hemorrhage was seen in 25.8 percent and 58.1 percent of patients clinically and dermatoscopically, respectively, and longitudinal melanonychia was seen clinically in 38.7 percent of patients and dermatoscopically in 61.3 percent of cases. The difference in observations made clinically and dermatoscopically was significant for both splinter hemorrhage and longitudinal melanonychia in LP, as these signs are better visualized by dermatoscopy than the naked eye and offer a better diagnostic clue. These findings were consistent with those of studies conducted by Nakamura et al,10 who observed longitudinal streaks (i.e., melanonychia) in 82.28 percent of cases and splinter hemorrhage in 35.44 percent of cases, whereas Bhat et al11 described longitudinal melanonychia in 66.67 percent of cases. Puri et al12 observed longitudinal melanonycha in only 20 percent of cases, demonstrating the dermatoscope as a great aid for identifying this important diagnostic clue.

Conclusion

Nail LP is a progressive disease affecting the paronychium nail bed and nail matrix in the evolutionary stages of the disease and finally converging to the more aggressive features of total nail dystrophy and anonychia. Histopathological examination, being an invasive technique, is not well regarded by patients, causing undue delay in diagnosis and treatment. By identifying various signs characteristically seen in nail LP, one can identify nail LP in the evolutionary stages and prevent progression through timely management. As a noninvasive and office-based tool, dermatoscopy constitutes a boon for diagnosis in such scenarios.

References

- De Berker DA, Richert B, Baran R. Acquired disorders of the nail and nail unit. In: Griffith CEM, Barker J, Bleikar T, Chalmers R, Creamer D, eds. Rook’s textbook of dermatology. 9th ed. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. 2016: 95.1–95.5.

- Arora SK, Chhabra S, Saikia UN, et al. Lichen planus: a clinical and immuno-histological analysis. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(3): 257–261.

- Tosti A, Piracinni BM. Biolology of nails and nail disorders. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrist BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Wolf K, eds. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine. 8th ed. New Delhi, India: McGraw-Hill; 2012: 1009–1012.

- Luis-Montoya P, Domínguez-Soto L, Vega-Memije E. Lichen planus in 24 children with review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(4):295–298.

- Friedman P, Sabban EC, Marcucci C, et al. Dermoscopic findings in different clinical variants of lichen planus. Is dermoscopy useful?. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5(4): 51–55.

- Grover C, Chaturvedi UK, Reddy BS. Role of nail biopsy as a diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78(3): 290–298.

- Grover C, Jakhar D. Onychoscopy: a practical guide. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83(5):536–549.

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007 Oct 20;370(9596): 1453–1457.

- Nakamura RC, Costa MC. Dermatoscopic findings in the most frequent onychopathies: descriptive analysis of 500 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(4):483–485.

- Nakamura R, Broce AA, Palencia DP, Ortiz NI, Leverone A. Dermatoscopy of nail lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(6):684–687.

- Bhat YJ, Mir MA, Keen A, Hassan I. Onychoscopy: an observational study in 237 patients from the Kashmir Valley of North India. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8(4): 283–291.

- Puri N, Kaur T. A study of nail changes in various dermatosis in Punjab, India. Dermatol Online. 2012;3(3):164–170.

- David BG, Kannan G, Babu P. A clinical study of nail changes in common papulosquamous disorders. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2017;26(4):332–336.