J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(10):16–18.

Medical Photography in the Age of Smartphone Cameras

Dear Editor:

Immortalizing disease images, first by moulages and later by photography, has been a critical part of dermatology since before we were a formal specialty. At its peak in the 20th century, many departments had staff medical photographers, while others had official “department cameras” to capture a variety of skin findings.

True democratization of image capture began in the mid-2000s with inexpensive camera phones that made image capture and storage simple and inexpensive. This “dumbing down,” making digital photography available worldwide, in our opinion has been associated with a loss of basic photographic principles for clinical photography, including non-distracting backgrounds, “standardized” views for reproducibility over time, and good lighting. The latter is most critical, as removal of backgrounds can be performed by apps and online services.

Lighting, from the perspective of good color reproduction by choosing an appropriate light source, and short exposure with a small aperture to give good depth of field and not have movement-related blurs, is critical to good quality images. At present, there are many LED light sources, in the shape of rings or circles, that clip onto cell phones, giving a color-balanced and consistent source of light. The ring’s placement around the lens gives flat illumination, useful for images in orifices, while placement off the side of the lens allows the light to function as more of a point source allowing shadows and the perception of texture and height of lesions.

We believe images taken using a cell phone or tablet should be illuminated with a bright external light source to allow the fastest exposure with the smallest aperture (controllable with many third-party apps) and the greatest detail. These lights also minimize the amount of illumination from ambient light sources, be it the warm yellow coloration of incandescent or halogen lighting or the sickly green of fluorescent lights that are common in exam rooms, offices and hospital rooms, further enhancing the standardization of images captured.

Searching on Amazon.com for “phone camera light” brings up over 9,000 matches, with some able to function as both a ring around the lens and as a point source of light, based on placement. Some allow color temperature selection ranging from warm white (yellow tinge, 2,000–3,000K) to cool white (blue tinge, 3,100–4,500K) to daylight (4,600–6,500K). We suggest using the daylight setting to further enhance consistency. Self-contained units with either a replaceable or rechargeable battery are inexpensive and convenient enough to meet the needs of most dermatologists (who are thoughtful about their image storage security to avoid issues with HIPAA non-compliance and associated penalties).

Based on working distance and magnification, some light sources may over-illuminate and wash out features. This can be solved by lowering light intensity or diffusing light by any of a number of simple techniques to get excellent images that enhance patient care and increase the likelihood of acceptance of images for publication.

With regard,

Daniel M. Siegel, MD, and Neal D. Bhatia, MD

Affiliations. Dr. Siegel is a Past President of the American Academy of Dermatology (2012–2013). Dr. Bhatia is the Vice President of the American Academy of Dermatology (2021–2022).

Funding. No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures. The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

Bony Resorption in the Mental Area due to Hyaluronic Acid Filler: A Complication to consider

Dear Editor:

The chin is a prominent feature of the lower third of the face, and an aesthetically pleasing jawline and chin contour are becoming essential components of facial rejuvenation.1,2 There are several methods of correcting a displeasing chin contour that range from invasive to noninvasive in nature.1–5 Hyaluronic acid (HA) injections are gaining popularity due to their ease of administration, reversibility, low downtime, and limited complication profile.2 Bony resorption at the mental area, while a known complication of chin implants, was only recently reported in the literature in a single case series of predominantly Asian descent.6–8 We would like to report a similar finding in a different ethnic group and a different pattern of bony resorption.

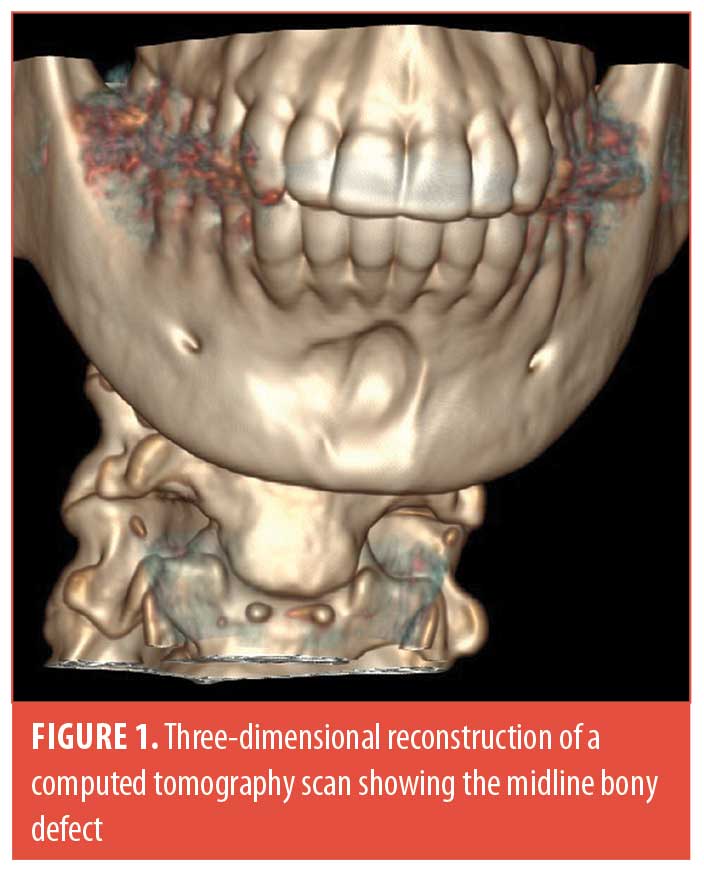

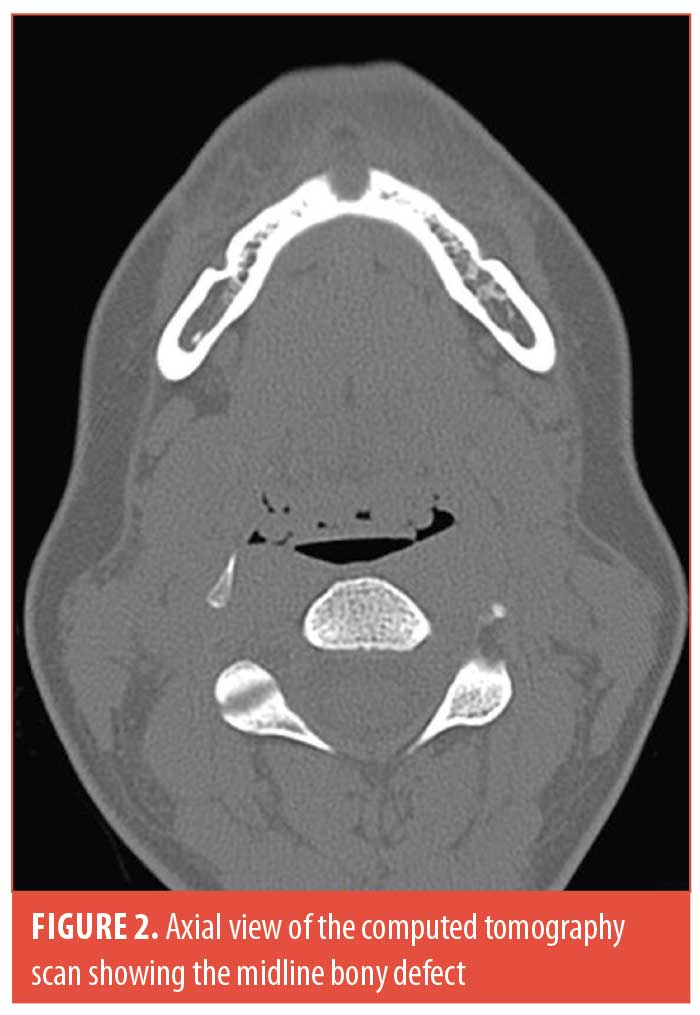

A 38-year-old woman of Middle Eastern descent underwent a total of four injections of 1 cc each as well as one injection of 2 cc of HA to the mental area (Juvéderm® Voluma™ [Allergan, Dublin, Ireland] and Restylane® Lyft [Galderma, Lausanne, Switzerland]) over a period of 40 months. The injection technique consisted of a central bolus of product “on bone.” She was referred to us after a panoramic x-ray, done for routine dental workup, suspected a cystic formation in the mental area. The patient was completely asymptomatic without evidence of infection or granuloma at the site of injection. A computed tomography scan revealed a semi-spherical bony erosion in the central symphyseal area without any cystic lesion (Figures 1 and 2). She underwent dissolution of the product using hyaluronidase to prevent any further bony damage.

Our patient had the same risk factors for bony resorption as described in the literature.8 She also had a completely asymptomatic presentation and an incidental finding of the bony resorption. However, our patient presented with a predominantly midline bony resorption corresponding to the product location, as opposed to what is currently reported in the literature, which states that the bony resorption is in majority paramedian with a preservation of the midline bony mass. This is the second report in the literature of bony resorption due to HA filler in the mental area, and the first to report midline erosion.

As a means of objectifying the rate of resorption, an index of paramedian to median bony resorption was reported in the study by Guo et al.8 Using this ratio would be inappropriate for evaluation of the bony resorption in our patient, as the ratio would be higher than 1, as opposed to the results from Guo et al.8 This ratio would also be unchanged in cases where the resorption is spread out over the entire mental area. Seeing as this is the first report of midline bony erosion, a ratio using symphyseal bony thickness would be henceforth inappropriate, as the whole area can be affected. We recommend using a different reference point, such as maxillary bony thickness, or any reference point along the mandible as this is has been demonstrated to be relatively stable with age.9

This case confirmed the possibility of bone erosion due to the injection of HA filler in the mental area in the non-Asian population, and, contrary to the cohort presented by Guo et al,8 it demonstrates that this resorption can also occur predominantly in the midline with a preservation of the incisive fossa bone mass. This should prompt more detailed studies regarding the safety of augmenting the mental area via HA injection as this patient is at increased risk of symphyseal fracture.

With regard,

Cyril Hanna, MD; Samer Jabbour, MD; and Marwan Nasr, MD

Affiliations. All authors are with the Plastic and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Hôtel Dieu de France Hospital in Achrafieh, Lebanon.

Funding. No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures. The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

References

- Mckee D, Remington K, Swift A, et al. Effective rejuvenation with hyaluronic acid fillers: current advanced concepts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(6):1277e–1289e.

- Moradi A, Shirazi A, David R. Nonsurgical chin and jawline augmentation using calcium hydroxylapatite and hyaluronic acid fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2019;35(02):140–148.

- Basile FV, Basile AR. Prospective controlled study of chin augmentation by means of fat grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(6):1133–1141.

- Ferretti C, Reyneke JP. Genioplasty. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2016;24(1):79–85.

- Newberry CI, Mobley SR. Chin augmentation using silastic implants. Facial Plast Surg. 2019;35(2): 149–157.

- Robinson M, Shuken R. Bone resorption under plastic chin implants. J Oral Surg. 1969;27(2):116–118.

- Guo X, Song G, Zong X, Jin X. Bone resorption in mentum induced by unexpected soft-tissue filler. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38(10):NP147–NP149.

- Guo X, Zhao J, Song G, et al. Unexpected bone resorption in mentum induced by the soft-tissue filler hyaluronic acid: a preliminary retrospective cohort study of Asian patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146(2):147e–155e.

- Kronseder K, Runte C, Kleinheinz J, et al. Distribution of bone thickness in the human mandibular ramus—a CBCT-based study. Head Face Med. 2020;16(1):13.

Generalized Granuloma Annulare Successfully Treated with Ustekinumab

Dear Editor:

We previously reported a case of a 58-year-old-woman with generalized granuloma annulare (GA) that did not respond to 28 weeks of treatment with tildrakizumab, a selective interleukin-23 inhibitor currently approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.1 Given that granuloma formation is mediated primarily by Th1 cytokines such as interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor, we posited that less selective inhibition with ustekinumab—an interleukin-12/-23 inhibitor which inhibits both Th17 and, more importantly, Th1 signaling—may be beneficial. Indeed, Hassoun et al2 reported a case of a granulomatous dermatitis that was successfully treated with ustekinumab.

Here, we report a case of a 70-year-old woman with generalized GA that cleared after 16 weeks of treatment with ustekinumab. The patient reported that her rash developed suddenly on her inner arms, thighs, and calves six weeks prior to presentation (Figure 1). Histopathology was consistent with granuloma annulare. She was initially treated with 60mg of triamcinolone (Kenalog; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, New York) intramuscularly, which led to a reduction in her pruritus without visible improvement in her skin lesions. She was then treated with three months of methotrexate, escalating to 15 mg per week with betamethasone augmented 0.05% cream without any further improvement. The patient was not a candidate for hydroxychloroquine or dapsone due to numerous drug–drug interactions. After four months of treatment failure, the patient agreed to off-label use of ustekinumab.

Four weeks after her first dose of ustekinumab (90 mg), the patient noted a significant reduction in her itching with decreased erythema in her lesions. She received subsequent doses of ustekinumab at Weeks 4 and 10. At her 16-week follow-up visit, the patient’s skin was clear with just barely perceptible post-inflammatory erythema (Figure 2). Given how well she was doing, the patient elected to stop further treatment.

Compared to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, which have also been shown to be effective in GA,3 the dosing regimen of ustekinumab is more favorable, and therefore it is easier to assess efficacy with drug samples before pursuing payor approval. We hope that our case will encourage other health care providers, and ultimately members of industry, to validate our initial findings through dedicated studies.

With regard,

Eingun James Song, MD, FAAD

Affiliations. Dr. Song is with North Sound Dermatology in Mill Creek, Washington.

Funding. No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures. Dr. Song has been a consultant, speaker, or investigator for AbbVie, Janssen, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, SUN, UCB, Sanofi &Regeneron, Incyte, and Castle Biosciences.

References

- Song EJ. Tildrakizumab ineffective in generalized granuloma annulare. JAAD Case Reports. 2021;7:3–4.

- Hassoun LA, Sivamani RK, Sharon VR, Silverstein MA, Burrall BA, Tartar DM. Ustekinumab to target granulomatous dermatitis in recalcitrant ulcerative necrobiosis lipoidica: Case report and proposed mechanism. Dermatol Online J. 2017.

- Torres T, Almeida TP, Alves R, Sanches M, Selores M. Treatment of recalcitrant generalized granuloma annulare with adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatology. 2011;10(12):1466–1468.