J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(1):15–17.

Seborrheic Melanosis: A unique under-recognized entity in ethnic skin

Dear Editor:

Seborrheic melanosis (SM) is an interesting clinical entity, primarily of cosmetic concern, that afflicts dark skin with seborrhea. It presents in ethnic (African, Asian, Hispanic) skin and has gained recent attention in the literature coming from the Indian subcontinent.1 Its distinct distribution pattern, morphological features and associated clinical findings help distinguish it from its close differentials. It is important to recognize this distinct clinical entity since certain management considerations differ from other forms of facial melanosis.

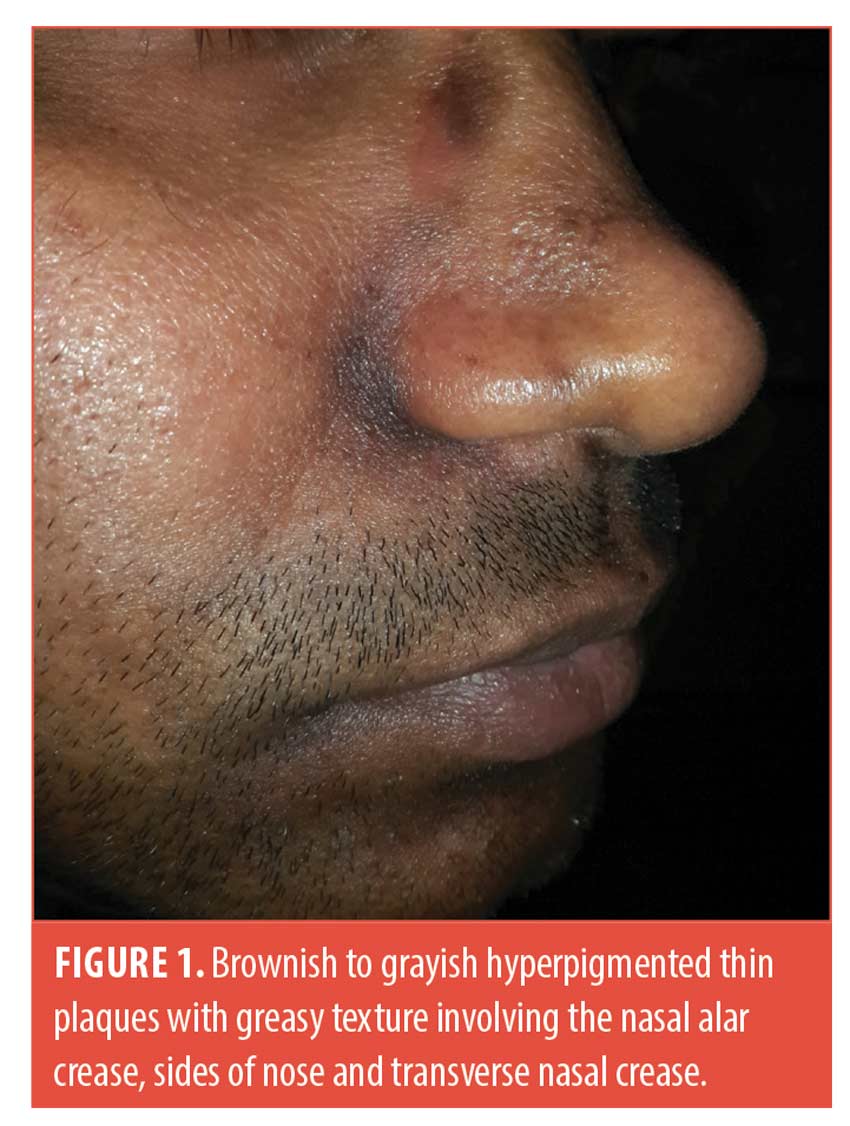

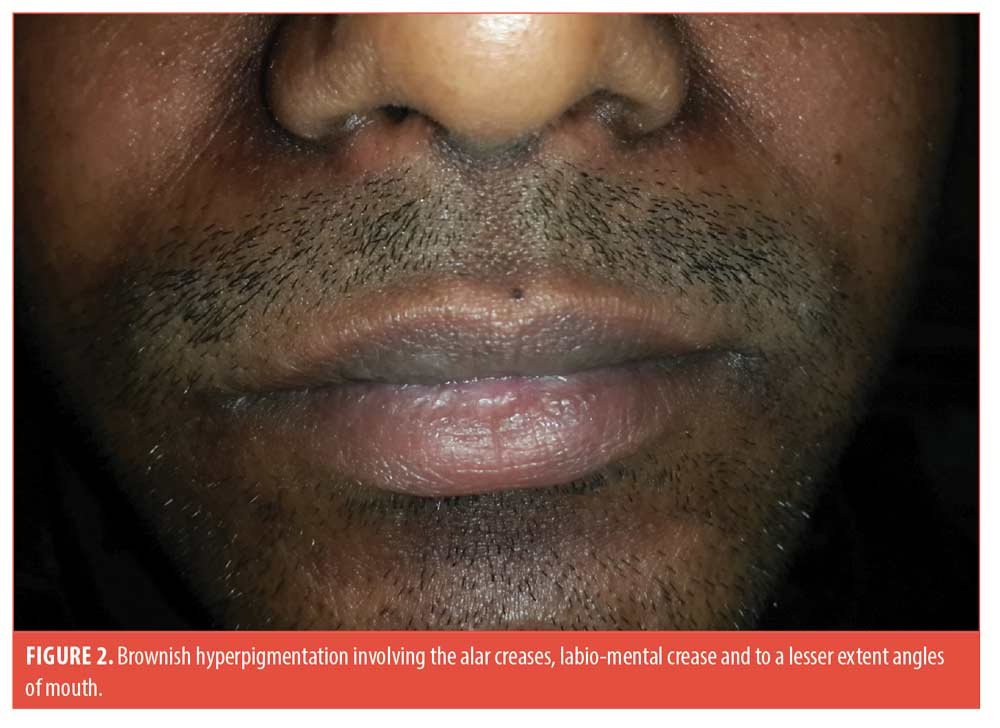

A 25-year-old man presented with asymptomatic brownish-to-grayish hyperpigmented thin plaques over the centrofacial areas (alar creases, sides of nose, labio-mental crease and to a lesser extent transverse nasal crease and angles of mouth). The lesions appeared greasy and velvety with faint perilesional erythema. The surrounding skin had an oily texture and the nose was bulbous (Figures 1 and 2). The condition was present for two years with history of winter exacerbation. There was no involvement of the forehead, beard, retroauricular area or trunk.

He did not recall any history of preceding flakiness or redness at these sites. He gave a history of “dandruff” though not apparent at the time of examination. There was no history of atopy, rubbing or spectacle usage. Biopsy was deferred in view of poor cosmetic outcome. A diagnosis of SM was made based on the classic clinical presentation. He was treated with 2% ketoconazole cream once a day, tacrolimus 0.1% ointment at night, a bland emollient and sun-protection.

SM is an interesting morphological entity characterized by localized darkening in the seborrheic areas with variable erythema. Fitzpatrick Skin Type IV and above are affected.1 Pruritus may be mild or absent. Given its characteristic seborrheic distribution, greasy texture and winter exacerbation, an association with seborrheic dermatitis (SD) cannot be overlooked. In fact, some hypothesize it to be a form of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) to SD in individuals with darker skin tones. Hence a history of preceding erythema or scaling (“flakiness”) in the involved sites should be sought, though mild erythema may be imperceptible in darker skin.1 Evidence of seborrhea such as oily skin texture, greasy appearance of lesions, dyssebacia (follicular plugs with inspissated sebum), pityriasis capitis, etc. are supportive findings. In addition to the characteristic seborrheic distribution of lesions, these should incline the clinician towards making a diagnosis of SM.2 These characteristics also help distinguish SM from “frictional melanosis” which occurs over bony prominences, does not obey classic seborrheic pattern/morphology and has a history of repeated rubbing.3

It is interesting to note, however, that there are certain pointers against simply equating SM to a post-inflammatory sequala of SD.4 A history of frank SD may not be present; a relatively bulbous nose (as in this patient [Figure 1] accentuates the alar and transverse nasal grooves allowing increased sebum accumulation in these areas without actual increase in sebum production.1,5 SM may often be completely asymptomatic.1 The labio-mental crease and angles of mouth are not typical sites for SD (but may be involved in perioral dermatitis, angular cheilitis etc.) and conversely, some classical sites of facial SD such as the eyelids, medial eyebrows are yet to be described for SM.1,4 Some authors speculate it to be a result of PIH due to multiple causes that have overlapping sites with SD.4

It is important for the dermatologist to recognize and identify SM as it is resistant to conventional lightening agents.3 Instead, topical anti-inflammatory/fungistatic agents effective in SD (topical calcineurin inhibitors, mild topical steroids and 2% ketoconazole cream) should be considered first, to allow any inflammatory component to subside. Topical lightening agents (e.g., kojic acid, azelaic acid, arbutin etc.) may be subsequently added at a later stage. It must be understood from a pathophysiological standpoint that while frictional melanosis, photo-melanosis and Riehl’s melanosis are different entities, triggers like sunlight/rubbing/cosmetics may work as additional components that contribute to/intensify the pigmentation of SM. Hence the holistic management of SM includes avoidance of these additional aggravating factors.1 The patient must be counseled regarding the slow treatment response, chronicity and innocuous nature of the condition.1,2

This is an attempt towards better describing SM which has till now been a rather ill-defined entity, especially since its histopathology is non-diagnostic and dermoscopy findings not well-established (the alar grooves and labiomental crease display variable degree of pigmentary, vascular and “seborrheic” dermoscopic changes even in normal individuals).2,4 Understanding the various considerations may help avoid a facial biopsy which may have cosmetic implications in dark-toned individuals. Though prima-facie facial melanoses of varied etiologies have considerable overlap in their clinical presentation, a suggestive distribution pattern and subtle morphological features guide the dermatologist towards a more specific diagnosis and help form a treatment strategy. While SM in ethnic skin has received special interest in the recent years, further studies may help to elucidate it further.

With regard,

Kanya Rani Vashisht, MD and Suruchi Garg, MD

Affiliations. Drs. Vashisht and Garg are with Aura Skin Institute in Chandigarh, India.

Funding. No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures. The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

References

- Verma SB, Vasani RJ, Chandrashekar L, Thomas M. Seborrheic melanosis: An entity worthy of mention in dermatological literature. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017; 83: 285-9.

- Bhatia V, Bubna AK, Subramanyam S, et al. Stubborn facial hypermelanosis in females: A clinicopathologic evaluation. Pigment Int. 2016; 3: 83-9.

- Al-Aboosi M, Abalkhail A, Kasim O, et al. Friction melanosis: a clinical, histologic, and ultrastructural study in Jordanian patients. Int J Dermatol. 2004; 43(4): 261–264.

- Arshdeep, Sonthalia S, Kaliyadan, F et al. Seborrheic melanosis and dermoscopy: Lumping better than splitting. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018; 84: 585-7.

- Cowley NC, Farr PM, Shuster S. The permissive effect of sebum in seborrhoeic dermatitis: An explanation of the rash in neurological disorders. Br J Dermatol 1990; 122: 71?6.

Coexistence of Bullous Pemphigoid and Pyoderma Gangrenosum

Dear Editor:

A 61-year-old man was admitted to our outpatient with a 20-day history of cutaneous blisters. Dermatological examination showed erythematous and edematous skin, surmounted by tense serous blisters on trunk and limbs (Figure 1). His medical history was positive for hypertension, thrombocytosis, haemorrhagic stroke. We performed skin biopsy, standard hematologic test, blood chemistry, research of BP-180 and BP-230 antibodies, abdominal echography and chest x-ray. Routine blood test showed eosinophilia (eosinophil: 16%-1,10×103/µL), thrombocytosis (platelet: 865×103/µL), increase of lactate dehydrogenase (298 U/l), creatine-kinase (331 U/l) and C-reactive protein (7.14 mg/dl), reduction of iron (29µg/dl); abdominal echography and chest x-ray were negative for malignancies. Histological findings and high levels of BP-180 and BP-230 antibodies (>100 U/ml and 6,5 U/mL respectively) confirmed the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. We started treatment with 50mg/daily of prednisone. After three weeks, blisters and erosions partially improved. In addition, wounds with a peripheral red halo, undermined edges and central granulomatous base appeared on ankles and feet, rapidly worsened and associated to severe pain (Figure 2). We augmented dosage of prednisone to 75mg/daily. Moreover, we performed cutaneous swab to rule out an infectious cause, resulting negative, doppler ultrasound of lower limb vessels, excluding venous and arteries’ insufficiency, and punch biopsy that confirmed our clinical suspect of pyoderma gangrenosum, for which we started a therapy with topical tacrolimus once daily. At the follow-up visit, dermatological examination showed a moderate wounds improvement and new bullous lesions. A 50mg/daily of azathioprine was added to systemic corticosteroids and we continued follow-up every three weeks with blood count. We didn’t obtain the remission of manifestations until the dosage of 100mg/daily of prednisone and 100mg/daily of azathioprine. After 15 weeks, the patient experienced a noticeable improvement in blisters and PG-related lesions, with a reduction in BP-180 antibody levels (Figure 3). Corticosteroid tapering was initiated and treatment has been ongoing for one year, without exacerbations.

BP is the most frequent bullous disorder. Differential diagnosis include other bullous diseases, eczema, urticaria, prurigo, impetigo, erythema multiforme, Sweet syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis and autotoxic pruritus.1 Among different possibilities, steroids remain the first line treatment.1 In our case a dosage of 100mg/daily of prednisone in association with 100mg/daily of azathioprine were necessary to obtain clinical remission. Despite the high dosages, the patient did not develop any adverse effects. PG is a rare autoinflammatory skin disease. The diagnosis is very difficult because of the wide spectrum of ulcerative skin conditions often misdiagnosed as PG3. The DELPHI and PARACELSUS scores aim to establish validated diagnostic criteria.3,4 Concerning the DELPHI score, the diagnosis requires the major criteria and at least four minor criteria.3 In our case, the biopsy was compatible with PG, confirming the major criteria and five of the eight minor criteria were respected. The PARACELSUS score includes 11 criteria: 3 major criteria, 4 minor criteria, and 3 addictional criteria, with the assignment of 3, 2 and 1 point respectively.4 The diagnosis requires at least 10 points. In our case the PARACELSUS score was 17, confirming the suspected diagnosis.

Our case is an example of how two rare pathologies can coexist in the same patient. Timely and careful diagnosis is needed to treat each manifestation in the best possible way. Since this is the only case reported in the literature, it isn’t possible to establish whether pathogenetic correlations exist.

With regard,

Adriana Di Guida, MD; Gabriella Fabbrocini, Phd; Massimiliano Scalvenzi, MD and Gaia De Fata Salvatores, MD

Affiliations. All authors are with the Section of Dermatology, Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery at University of Naples Federico II in Naples, Italy.

Funding. No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures. The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

References

- Miyamoto D, Santi CG, Aoki V. et al. Bullous pemphigoid. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94(2):133–146.

- Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pathophysiology of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Oct;73(4):691-8. 2015 Aug 5. PMID: 26253362.

- Jockenhöfer F, Wollina U, Salva KA et al. The PARACELSUS score: a novel diagnostic tool for pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(3):615-620.

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic Criteria of Ulcerative Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Delphi Consensus of International Experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(4):461-466.