J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(11):26–30.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(11):26–30.

by Hamed Mohamed Abdo, MD; Emad M. Elrewiny, MD; Ahmed Shawky, MD; Amr Mohammad Ammar, MD;

Ahmed Mohammed Atef, MSc; and Mahmoud A. Rageh, MD

All authors are with the Department of Dermatology and Faculty of Medicine at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Objective. Alopecia areata (AA) is a common form of potentially reversible non-scarring hair disorder characterized by limited patchy hair loss (alopecia areata), loss of all scalp hair (alopecia totalis), or all body hair (alopecia universalis). Several lines of treatment have been used with variable outcomes. We aimed to compare the efficacy of intralesional pentoxifylline (PTX) and triamcinolone acetonide (TRA) injection in the treatment of alopecia areata.

Methods. Our study included 60 patients with localized AA recruited from the Dermatology Outpatient Clinics of Al-Azhar University Hospitals. Patients were divided into two groups of alopecia areata patches; Group A who received intralesional TRA injections while Group B received intralesional PTX.

Results. The study showed that both modalities are effective in treating AA and each modality has its own advantages. According to the response, patients were grouped into three categories: partial response (0-33% terminal hair regrowth), moderate response (33-66% terminal hair regrowth), and high response (66-100% terminal hair regrowth). The high response after use of the PTX was found in 50 percent of patients. The high response was observed in 46.6 percent of patients treated with TRA.

Limitations. Small sample size and short follow-up period.

Conclusion. This study showed that intralesional injection of PTX seems to be effective and safe treatment for localized AA and could be used as a good alternative to triamcinolone acetonide.

Keywords. Alopecia areata, hair loss, triamcinolone acetonide, pentoxifylline

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune condition caused by T cell attacks on hair follicles (HFs) compromising their immunological privilege and causing temporary hair loss that can persist for weeks to decades with significant psychologic impact on affected individuals.1

Accordingly, it has been reported that CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and natural killer cells (NK), prominently infiltrate anagen HFs in active AA lesions. However, there has been no useful biological marker for AA.2

A variety of therapeutic options have been used for treating AA such as corticosteroids, minoxidil, methotrexate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine. The relapse rate is significant with these therapeutic agents. In addition, most of these treatments have serious side effects.3

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has given the methylxanthine derivative pentoxifylline (PTX) approval for the treatment of intermittent claudication. However, studies have revealed that it also has a variety of physiological effects at the cellular level that may be crucial in the treatment of a wide range of diseases.4

This study aimed to compare the effect of intralesional pentoxifylline (PTX) and triamcinolone acetonide (TRA) injection in treating AA.

Methods

Study design. This case comparative study was conducted at the Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt after approval by the Research Ethics committee (Approval No. Der-Med.21.Research.0000728). Written consent was obtained from all participants after being informed about the nature of the study, the expected outcome, and the possible complications.

Study population. Sixty patients with localized AA and no history of previous treatment for at least one month prior to the study were enrolled. Patients younger than 18 years, patients with alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, ophiasis, cicatricial alopecia, patients with hematological disorders, and/or other causes of alopecia other than AA were excluded from the study.

Each patient was subjected to full clinical history, general examination, full dermatological examination of skin, hair, and nails, dermoscopic assessment, and photography at the beginning and the end of the sessions.

Materials used. Triamcinolone acetonide vials (40mg/mL), pentoxifylline ampoules (100mg/5mL), and insulin syringes (100-unit, 30G needle).

Patient classification. Patients were randomly divided into two groups of AA patches; Group A received intralesional triamcinolone acetonide diluted in normal saline to a concentration of 5mg/mL, with a session-maximum dose of 20mg TRA, while Group B received intralesional PTX with a maximum of 20mg (1mL) per session. All patients received a treatment session every two weeks up to five sessions. Injections were done under strict sterile conditions.

Evaluation of the response. According to the percentage of hair regrowth, the response to therapy was divided into three categories: high response (66-100% hair regrowth), moderate response (33-66% hair regrowth), and partial response (0-33% hair regrowth).5 Dermoscopic evaluation for signs of AA was also performed. The evaluation was done by two non-treating blinded dermatologists to minimize potential bias.

Statistical analysis. The collected data were revised, coded, tabulated, and introduced to a PC using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), Version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), Median and IQR (Interquartile Range). Qualitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage. Independent-samples T-test was used when comparing between two means (for normally distributed data). Mann–Whitney U test: was used when comparing between two means (for abnormally distributed data). Fisher’s exact test was used when comparing between non-parametric data.

Results

This study included 60 patients (33 females and 27 males) suffering from localized AA. The mean age of the studied patients was 30.25 ± 9.1 years.

From baseline evaluations, there was no statistically significant difference (p-value > 0.05) between studied groups regarding age, sex, duration, previous episodes, number of lesions, site of lesions, nail changes, number of sessions, family history of alopecia areata, history of autoimmune diseases, and smoking. Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) between studied groups as regards previous treatment was found (Table 1).

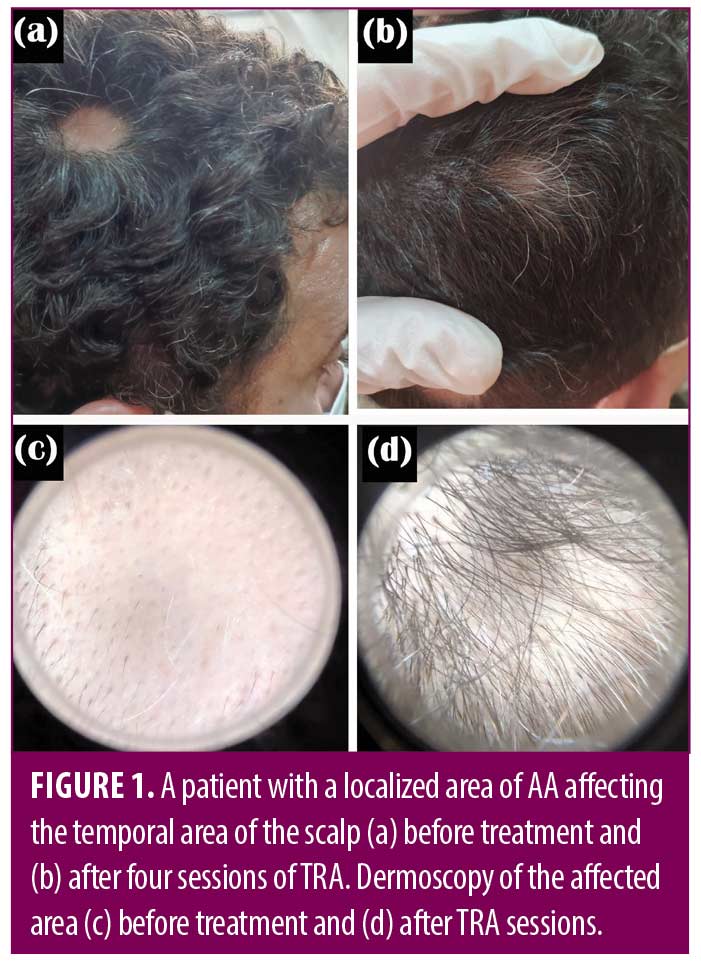

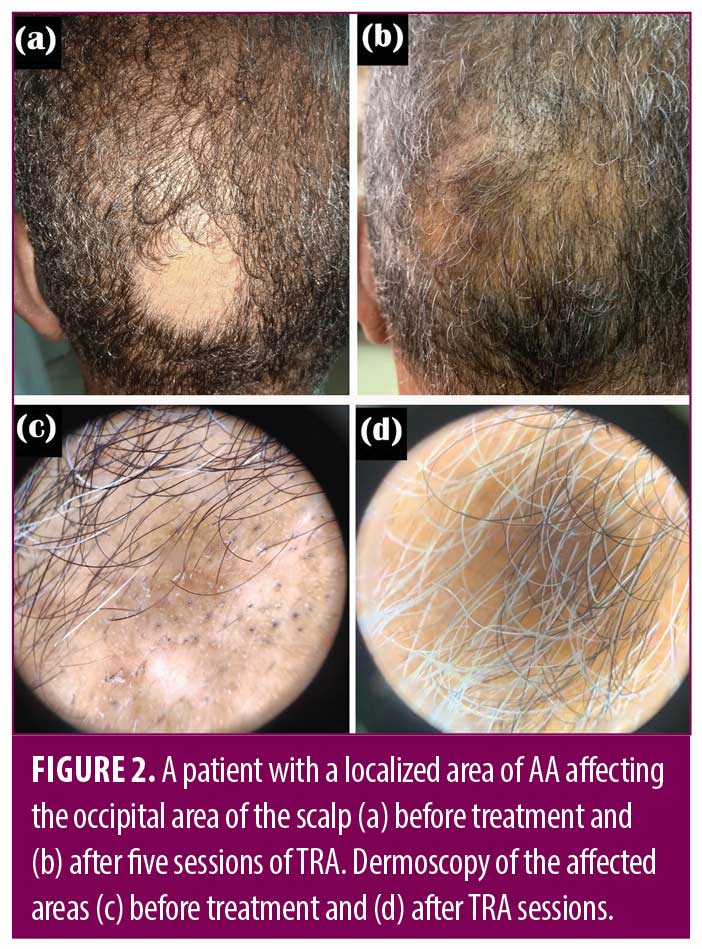

In Group A, the dermoscopic evaluation showed no statistically significant difference in yellow dots, short vellus hair, and pigtail hair (before and after treatment). However, there was a highly statistically significant difference (p-value <0.001) in black dots, exclamation marks, and broken hair (before and after treatment) in the same group (Table 2).

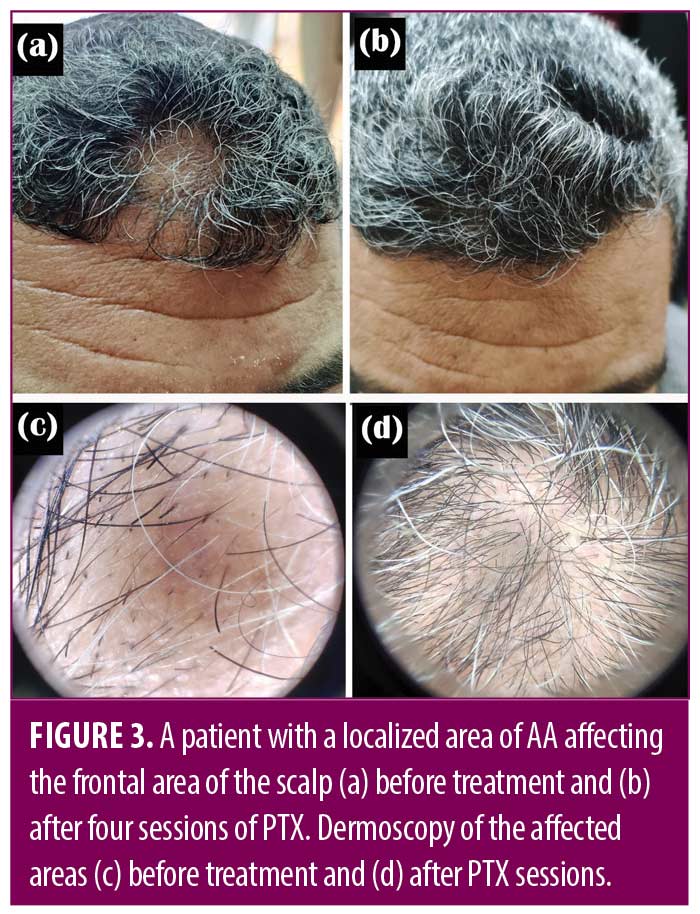

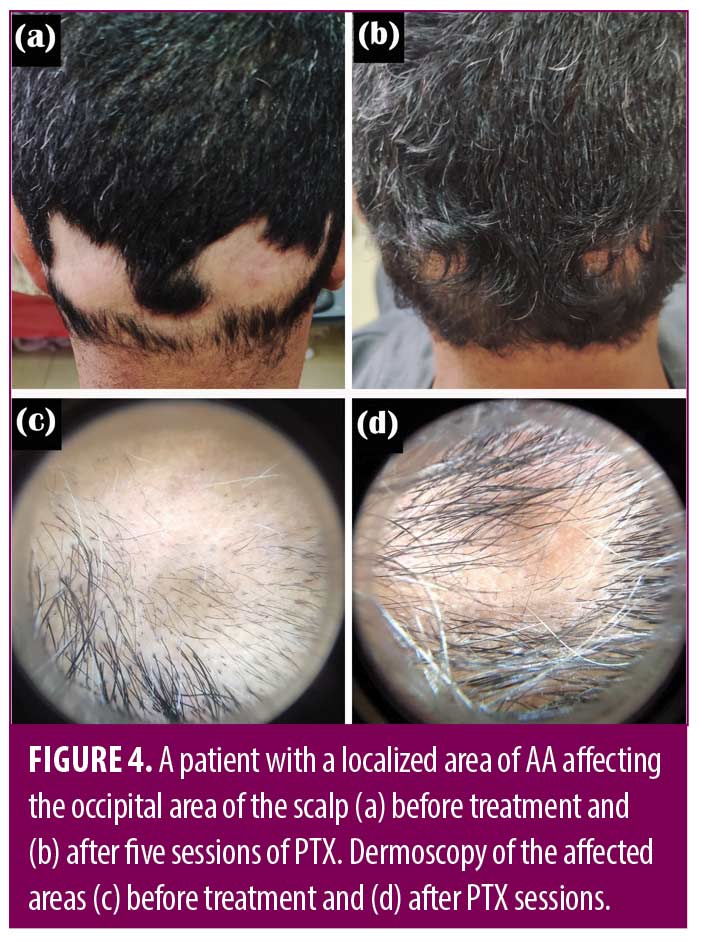

In Group B, the dermoscopic evaluation showed no statistically significant difference in yellow dots, short vellus hair, and pigtail hair (before and after treatment). There was a highly statistically significant difference in black dots and a statistically significant difference in exclamation marks and broken hair (before and after treatment) in the same group (Table 3).

There was no statistically significant difference between the studied groups as regard treatment response (Table 4) (Figures 1-4).

As regards side effects, PTX-treated group showed no side effects while in TRA-treated group 4 (13.3%) patients illustrated slight atrophy.

Discussion

Alopecia areata is a common autoimmune disorder characterized by non-scarring alopecia. It affects males and females equally, commonly in the first two decades of life, and usually presents as well-defined skin-colored patches of hair loss. Based on the extent of hair loss, the disease is classified into patchy hair loss (AA), alopecia totalis (AT), where there is loss of entire scalp hair, or alopecia universalis (AU), where there is a total loss of all body hair. AA can be associated with nail changes, autoimmune disorders, and psychological and eye abnormalities.6,7

In most cases, the diagnosis of AA is strictly clinical, and no additional investigation is usually required. Dermoscopy is an additional tool that helps in diagnosing and differentiating AA from other morphologically similar diseases associated with hair loss. The main dermoscopic features of AA are yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, exclamation mark hairs, and short vellus hairs.8

Alopecia areata has been treated with a variety of medications, but few have been tested in randomized controlled trials and none have been approved by FDA.9

Intralesional steroid injection is one of the most effective treatments in patchy alopecia areata via stimulating hair regrowth.10 In 1958, using hydrocortisone was the first attempt to utilize intralesional corticosteroids in treating AA.11 T-cell mediated immunological assault on HFs is suppressed by corticosteroids. TRA, triamcinolone-hexacetonide, and hydrocortisone-acetate are among the medications utilized. Because it is less atrophogenic than triamcinolone-hexacetonide, TRA is the commonly chosen intralesional product. In addition, steroids with limited solubility are recommended since they absorb slowly from the injection site, enabling maximum local impact with minimal systemic influence.12,13

Pentoxifylline is a methyl-xanthine derivative with multiple anti-inflammatory effects. It has been used in many dermatological conditions with proven efficacy. However, it’s only been FDA-approved for treating intermittent claudication.14 PTX increased red blood cell deformability and decreased blood viscosity by increasing erythrocyte adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and other cyclic nucleotide levels.15

PTX affects almost all factors responsible for blood viscosity and is considered the first known hemorheologically active drug.16 It reduces inflammation by blocking pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8. Additionally, PTX effectively inhibits T lymphocyte activation and cell adhesion, decreases ICAM-1 surface expression, impedes natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxic effects, and enhances the T-helper type 2 (Th2) response.17,18

Local atrophy upon repeated steroid injections is reported along with hypopigmentation and telangiectasia.19 PTX, on the other hand, has a vasculogenic protective effect via vasodilatation mediated through decreasing the oxidative stress and the associated inflammation, particularly in disorders like AA.20,21

PTX hemorheologic effects correct microcirculatory disorders thus increasing tissue nutrition and preventing the risk of atrophy. Its actions prevent thrombus formation via decreasing plasma fibrinogen and increasing fibrinolytic activity.22

Results of this study showed that PTX has a potent therapeutic effect in localized AA with less incidence of atrophy.

Pentoxifylline has been used in the treatment of fibrosis. It blocks TNF-α-induced synthesis of fibroblasts.23 Moreover, other reports demonstrated the effect of PTX in attenuating and reversing fibrotic lesions.24

When PTX-only treated patients were evaluated, 50 percent of patients showed high response, while only 23.3 percent showed partial response. These findings are better when compared to TRA-treated patients.

Trevisan and Cisilin recognized that oral PTX corrected hemorheologic parameter abnormalities in patients with AA.21 Our study also agrees with El-Taweel et al25 who found that PTX is efficient in treating localized AA.

Conclusion

Pentoxifylline seems to be an effective and safe treatment option for patients suffering from localized AA and has fewer incidence rates of localized atrophy following injections and can be used as a good alternative to triamcinolone acetonide. More studies on larger populations with longer follow-up periods should be performed.

References

- Blume-Peytavi U, Vogt A. Translational Positioning of Janus Kinase (JAK) Inhibitors in Alopecia Areata. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(4):282–283.

- Ono S, Otsuka A, Yamamoto Y, et al. Serum granulysin as a possible key marker of the activity of alopecia areata. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;73(1):74–79.

- Singh S. Role of platelet-rich plasma in chronic alopecia areata: Our centre experience. Indian J Plast Surg. 2015;48(1):57–59.

- Pascarella L, Schönbein GW, Bergan JJ. Microcirculation and venous ulcers: a review. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19(6):921–927.

- Rashidi T, Mahd AA. Treatment of persistent alopecia areata with sulfasalazine. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(8):850–852.

- Alkhalifah A. Topical and intralesional therapies for alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24(3):355–363.

- Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, et al. Alopecia areata update: part I. Clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(2):177–188, quiz 89–90.

- Mubki T, Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, et al. Evaluation, diagnosis of the hair loss patient: part II, Trichoscopic and laboratory evaluations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:431.e431–431.e411.

- Pratt CH, King LE Jr, Messenger AG, et al. Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17011.

- Kubeyinje EP. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide in alopecia areata amongst 62 Saudi Arabs. East African Med J. 1994;71:674–675.

- Garg S, Messenger AG. Alopecia areata: evidence-based treatments. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28(1):15–18.

- Madani S, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(4):549–566; quiz 567–570.

- Shapiro J, Price VH. Hair regrowth. Therapeutic agents. Dermatol Clin. 1998;16(2):341–356.

- Hassan I, Dorjay K, Anwar P. Pentoxifylline and its applications in dermatology. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(4):510–516.

- Zargari O. Pentoxifylline: a drug with wide spectrum applications in dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14(11):2.

- Ely H. Pentoxifylline therapy in dermatology. A review of localized hyperviscosity and its effects on the skin. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6(4):585–608.

- Krakauer T. Pentoxifylline inhibits ICAM-1 expression and chemokine production induced by proinflammatory cytokines in human pulmonary epithelial cells. Immunopharmacology. 2000;46(3):253–261.

- Fujimoto T, Nakamura T, Furuya T, et al. Relationship between the clinical efficacy of pentoxifylline treatment and elevation of serum T helper type 2 cytokine levels in patients with human T-lymphotropic virus type I-associated myelopathy. Intern Med. 1999;38(9):717–721.

- Downs AM, Lear JT, Kennedy CT. Anaphylaxis to intradermal triamcinolone acetonide. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(9):1163–1164.

- Azhar A, El-Bassossy HM. Pentoxifylline alleviates hypertension in metabolic syndrome: effect on low-grade inflammation and angiotensin system. J Endocrinol Invest. 2015;38(4):437–445.

- Trevisan G, Cisilin MP. Alopecia areata. Hemorheological study and treatment with pentoxifylline. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1988;123(5):211–214.

- Çakmak SK, Çakmak A, Gönül M, et al. Pentoxifylline use in dermatology. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2012;11(6):422–432.

- Samlaska CP, Winfield EA. Pentoxifylline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(4):603–621.

- Wen WX, Lee SY, Siang R, et al. Repurposing pentoxifylline for the treatment of fibrosis: an overview. Adv Ther. 2017;34(6):1245–1269.

- El-Taweel AI, Akl EM. Intralesional pentoxifylline injection in localized alopecia areata. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(2):602–607.