by Andrew J. Krispinsky, MD; Polina V. Rzepka, MD; Farrukh Awan, MD; and Benjamin H. Kaffenberger, MD

by Andrew J. Krispinsky, MD; Polina V. Rzepka, MD; Farrukh Awan, MD; and Benjamin H. Kaffenberger, MD

Drs. Krispinsky, Rzepka, and Kaffenberger are with the Division of Dermatology and Dr. Awan is with the Division of Hematology— all from the Department of Internal Medicine at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center in Columbus, Ohio.

Funding/disclosures. Dr. Awan reports he is a consultant for AbbVie, Pharmacyclics, Gilead, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals and has received research funding from Pharmacyclics. The other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Dear Editor:

We present a case of a man in his 50s with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). He was diagnosed with CLL four years prior and had undergone multiple treatment regimens, including fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab, ibrutinib, and acalabrutinib. Given his progressive disease, he was started on venetoclax and MOR00208 (a humanized Fc-engineered anticluster of differentiation 19 antibody). His other medications included escitalopram, hydroxychloroquine, prednisone, and simvastatin, as well as intravenous immunoglobulins administered every 6 to 8 weeks. After receiving his first dose of MOR00208, he was admitted for close inpatient monitoring given the risk of tumor lysis with venetoclax.

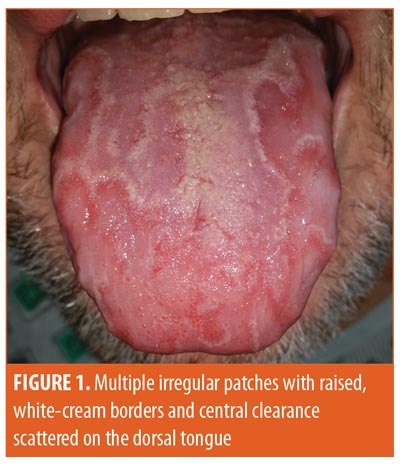

Dermatology was consulted upon the appearance of asymptomatic lesions on the tongue, which occurred several days after his first dose of venetoclax. Further physical examination revealed multiple irregular patches with raised, white-cream borders and central clearance scattered on the dorsal tongue (Figure 1). He denied dysgeusia, glossal pain, or systemic symptoms at the time. Febuxostat, started prior to initiating venetoclax, was the only other new medication reported by the patient. Given the appearance, the diagnosis of geographic tongue was made. The lesions remained asymptomatic and resolved after several months while his treatment with venetoclax was ongoing.

Discussion. In 2016, venetoclax was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of patients with CLL and a chromosome 17p deletion who have attempted at least one other therapy. Venetoclax is a selective inhibitor of the BCL2 protein, an antiapoptotic protein that is often highly expressed in CLL, allowing for the uncontrolled proliferation of malignant cells. Venetoclax has demonstrated the ability to induce a rapid onset of apoptosis of CLL cells and shows promise in treating other types of refractory CLL.1 The most common adverse events reported in a Phase II clinical trial were nausea, diarrhea, and neutropenia,1 with no significant cutaneous or oral effects reported to date.

The development of geographic tongue in our patient occurred within days of initiating venetoclax. Although the etiology of geographic tongue is not well understood, it is commonly associated with psoriasis. The characteristic atrophic red patches lack filiform papillae, which histologically possess a keratinized epithelium.2 Interestingly, studies investigating the role of BCL2 in oral carcinoma have shown that BCL2 expression is confined to the regenerative basal layer of the normal oral mucosa.3,4 In leukoplakia, an oral disease characterized by hyperkeratosis, high levels of BCL2 were found in basal mucosal cells.5 Increased levels of BCL2 expression have been observed in the basal layer of poorly differentiated carcinomas of the oral cavity,3 and diffusely in basal cell carcinomas.6

Conclusion. Given the temporal relationship between the administration of venetoclax and the development of geographic tongue, we hypothesize that venetoclax moderated the proliferation of the normal regenerative basal layer, resulting in characteristic mucosal atrophy. Our report describes a unique dermatologic toxicity caused by targeted BCL2 inhibition; however, one case cannot conclusively establish its etiology. Further research is needed to determine the frequency and mechanism of this event and the role of BCL2 inhibition in orocutaneous keratinocyte carcinomas.

References

- Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst B, Schetelig J, et al. Venetoclax in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6): 768–778.

- Banoczy J, Szabo L, Csiba A. Migratory glossitis. A clinical-histologic review of seventy cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;39(1):113–121.

- Jordan RC, Catzavelos GC, Barrett AW, Speight PM. Differential expression of bcl-2 and bax in squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1996;32B(6):394–400.

- Nunez MA, de Matos FR, Freitas Rde A, Galvao HC. Immunohistochemical study of integrin alpha(5)beta(1), fibronectin, and Bcl-2 in normal oral mucosa, inflammatory fibroepithelial hyperplasia, oral epithelial dysplasia, and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2013;21(4):354–361.

- Pigatti FM, Taveira LA, Soares CT. Immunohistochemical expression of Bcl-2 and Ki-67 in oral lichen planus and leukoplakia with different degrees of dysplasia. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(2):150–155.

- PuizinaIvic N, Sapunar D, Marasovic D, Miric L. An overview of Bcl-2 expression in histopathological variants of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis and seborrheic keratosis. Coll Antropol. 2008;32 Suppl 2:61–65.