J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(9):54–58.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(9):54–58.

by Alfredo Rossi, MD, PhD; Giulia Tadiotto Cicogna, MD; Gemma Caro, MD; Maria Caterina Fortuna, MD; Francesca Magri, MD; and Sara Grassi, MD

Drs. Rossi, Fortuna, Caro, Magri, and Grassi are with the Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties, Dermatology at the Sapienza University of Rome in Rome, Italy. Dr. Tadiotto Cicogna is with the Unit of Dermatology at the University of Padua in Padua, Italy.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a scarring alopecia that has been reported mostly in postmenopausal women and is characterized by frontotemporal hairline. Currently, there are only a few reports about FFA in male patients.

Objective. This study sought to analyze clinical and trichoscopic features of FFA in a case series of men and to describe the main features of FFA in male patients through a review of the literature.

Methods. Male patients with clinical and trichoscopical signs of FFA, histologically confirmed, who attended to our clinic from 2014 to 2019 were included in our study. From each patient, clinical and trichoscopic data were collected.

Results. Eight men with an average age of 59 years were recruited. In five patients, serrated hairline recession (i.e., a “zig-zag” pattern) was present, while three presented with linear hairline recession. Also, the eyebrows (n=3 patients), sideburns (n=2 patients), and beard (n=2 patients) were involved. Surprisingly, in two patients, an association with lichen sclerosus (LS) was present.

Conclusion. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a serrated hairline recession pattern in male patients with FFA. A new association between FFA and LS in men was also found. Further studies need to establish the extent of this association and facilitate a better comprehension of the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying these two diseases.

Keywords: Frontal fibrosing alopecia, male sex, scarring alopecia, trichoscopy; comorbidities, lichen sclerosus

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a lymphocytic scarring alopecia, generally presenting with frontotemporal hairline recession, that is frequently associated with eyebrow loss and facial papules.1 FFA was first described by Kossard1 in 1994 as a peculiar type of scarring alopecia affecting menopausal women, and the number of premenopausal patients reported in the literature has increased over the last decade.1 In 2002, Stockmeier2 described the first male case of FFA and, since then, a few single case reports or small case series have been published.3

The pathogenesis of FFA is still unclear and, since its first description, FFA has been considered a clinical variant of lichen planus pilaris (LPP); however, this association remains under debate.4

This study sought to analyze clinical and trichoscopic features of FFA in male patients and to evaluate the association of FFA with other diseases. Moreover, a review of the literature was performed to underline the main features of FFA in men.

Methods

An observational prospective study of male patients affected by FFA was conducted. Patients were recruited over a five-year period, between September 2014 and September 2019. Male patients with clinical and trichoscopical signs of FFA were included in the study, after histopathological confirmation with a punch biopsy.

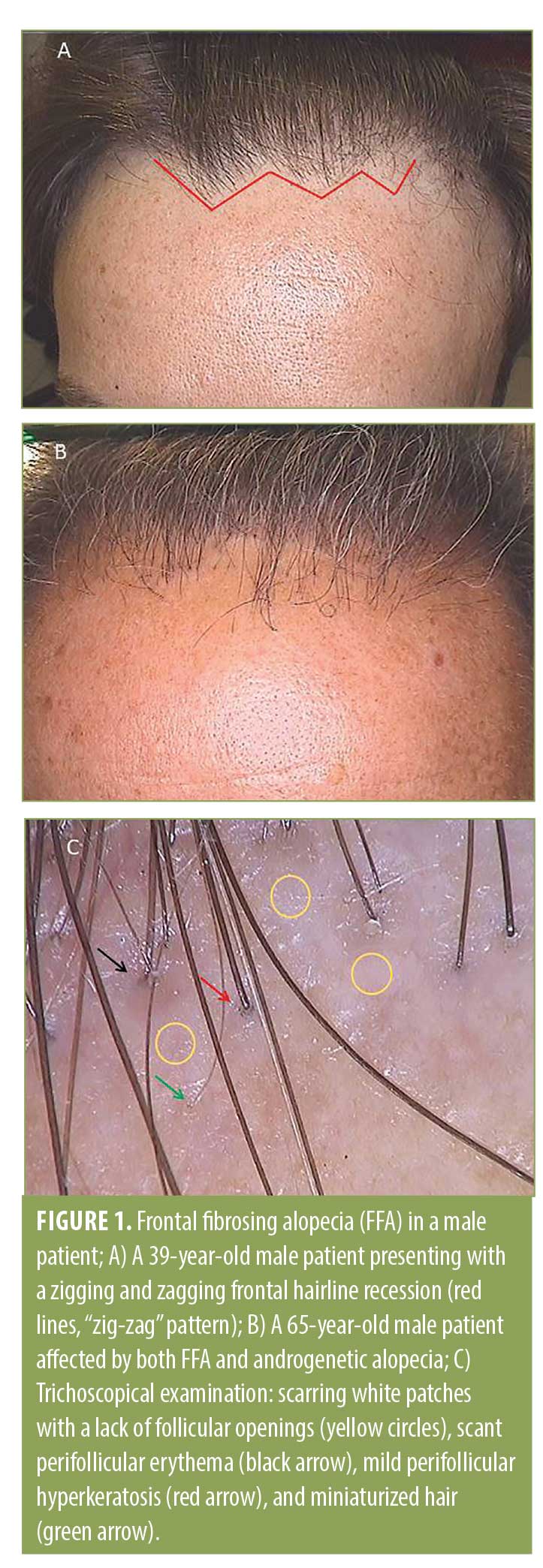

The clinical criteria considered for the diagnosis were the following: scarring alopecia of the forehead and/or temples with or without the involvement of additional FFA sites, such as the eyebrows, sideburns and beard. Trichoscopic criteria, considered at the frontotemporal hairline, included the presence of perifollicular erythema, mild perifollicular hyperkeratosis, and an absence of follicles.

For each patient included in the study, medical history data were collected in order to document comorbidities, age at onset of the disease, and the use of facial sunscreen creams. In clinical and trichoscopic evaluations, the following data were recorded: localization of the disease (forehead and temples, eyebrows, sideburns, and beard), the co-existence of facial papules, the presence of pruritus as a first symptom, and erythema and hyperkeratosis perifollicular. The degree of recession of the hairline was estimated at the forehead and temples by measuring, in centimeters, the distance from the frontal hairline to the glabella. Furthermore, a complete clinical examination of skin, mucous membranes, and nails was performed to identify signs of lichen planus (LP). The presence of other types of alopecia, such as androgenetic alopecia (AGA) and alopecia areata (AA), was assessed.

A blood workup, including thyroid hormones, antithyroid antibodies, and antinuclear antibodies, was carried out in all cases.

A systematic review of literature indexed in PubMed, Google Scholar, or Scopus was carried out to locate articles published before October 2019 with the following terms included in the abstract or in the title: “frontal fibrosing alopecia” and “male” or “man.”

Results

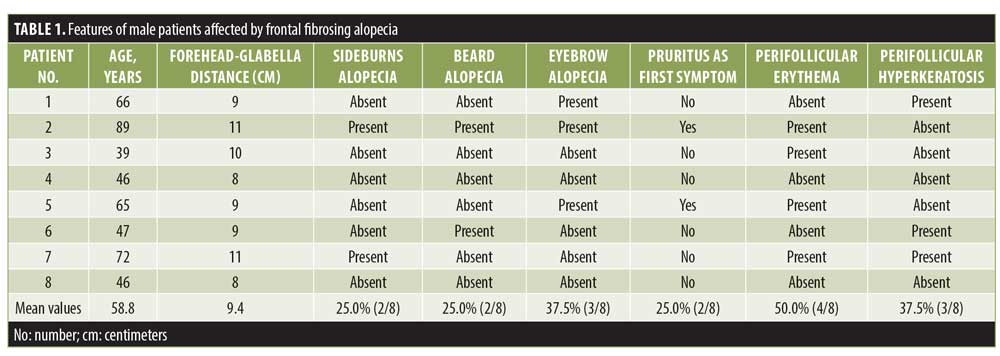

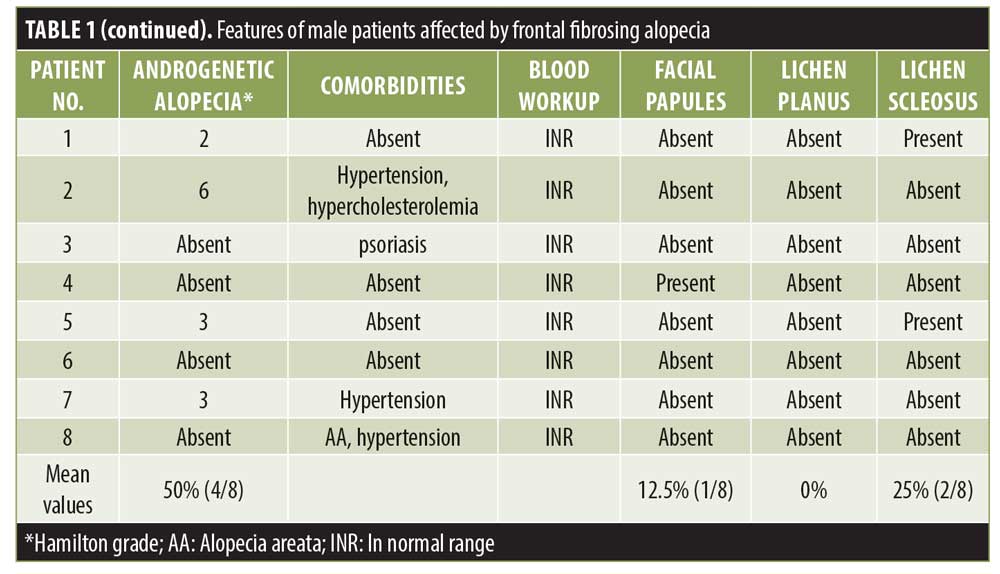

Eight Caucasian adult male patients were enrolled. Patients’ clinical features and laboratory findings are summarized in Table 1. All patients denied habitual use of facial sunscreen creams.

Interestingly, in five patients, a serrated line recession of the frontotemporal hairline (“zig-zag” pattern) was observed (Figure 1), while three patients presented with linear hairline recession. Nape involvement was not observed in any case. Also, the eyebrows (n=3 patients), sideburns (n=2 patients), and beard (n=2 patients) were involved. Surprisingly, in two patients (Patients 1 and 5; Table 1), an association with lichen sclerosus (LS) was identified. In both patients, LS onset preceded FFA onset (by 12 and 28 months, respectively). At clinical evaluation, atrophic ivory-white patches in the balano-preputial area were present in both cases with involvement of the glans present in Patient 5 as well. Treatment with local clobetasol cream and vitamin E five times per week for three months, then twice per week was started, with subsequent resolution of itching and sexual activity impairment. At the time of FFA diagnosis, LS was clinically stable and asymptomatic in both patients.

At the frontotemporal hairline, lonely hairs were present in all patients, whereas vellus hair were totally absent. At tricoscopical examination, empty follicles and white dots were a common finding at the hairline in all the patients.

During histopathological examination, peri-infundibular and peri-isthmal lymphocytic infiltrates and concentric follicular fibrosis, infundibular dilation, and hypergranulosis were observed in all biopsy specimens.

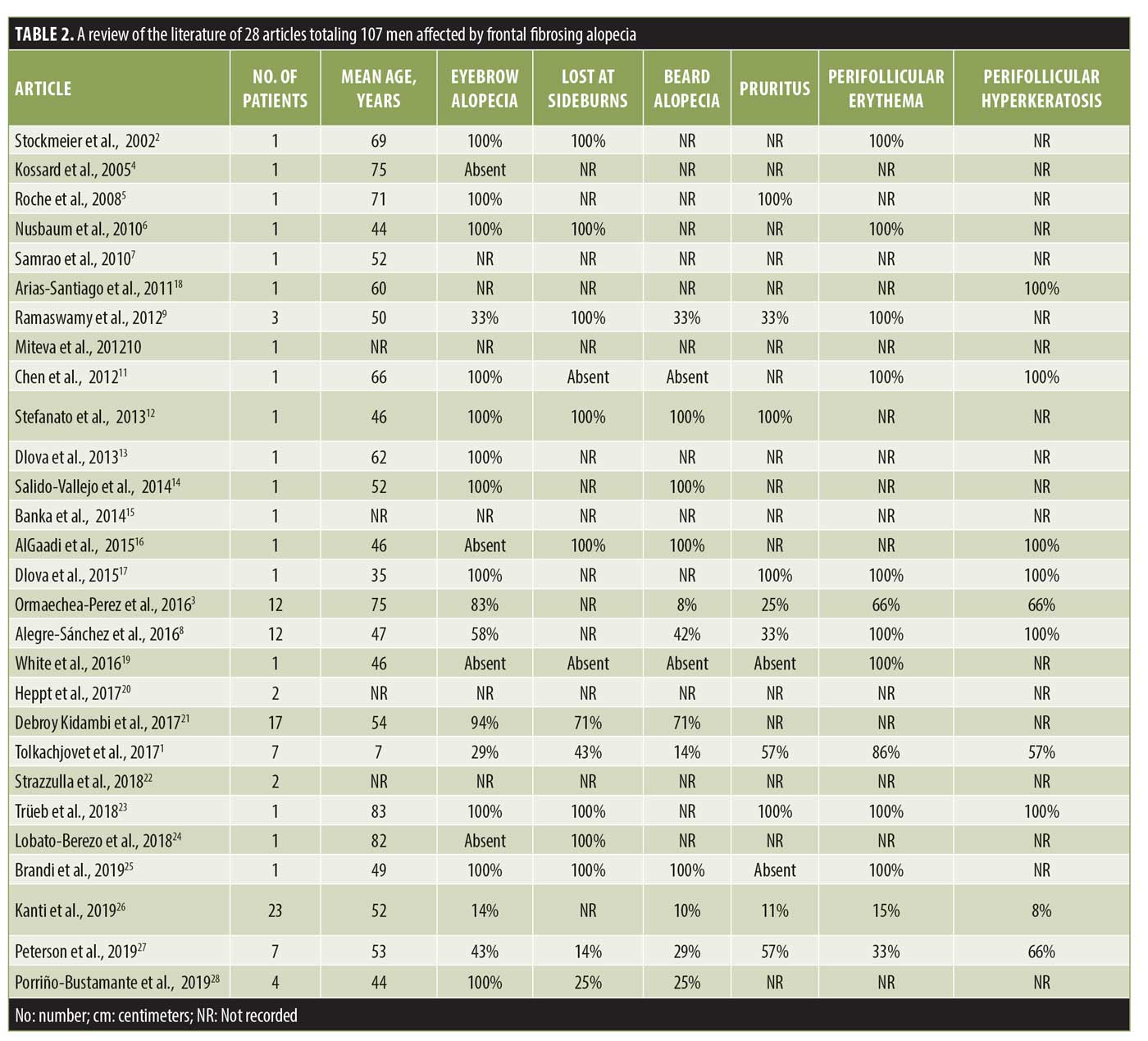

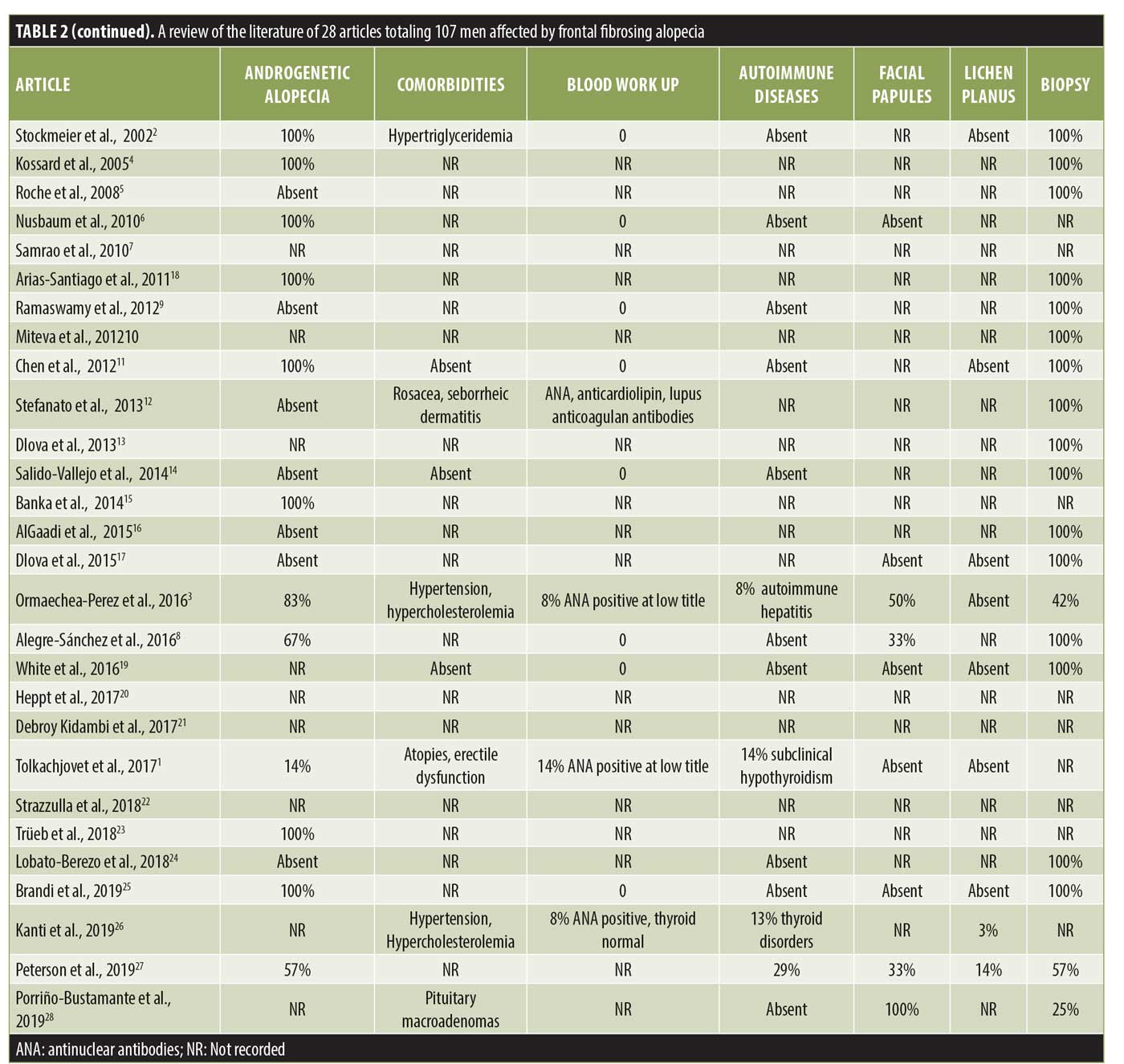

Following a review of the literature, 28 articles with a total of 107 men affected by FFA were identified and analyzed (Table 2).1–28

Discussion

FFA was firstly described as a peculiar type of alopecia that occurs in postmenopausal women.1 Since the first case of FFA in a man reported in 2002,2 107 male patients with FFA have been reported in the literature to date.1–28 We believe that these data may be underestimated because of the frequent association of FFA with AGA that, if severe, could mask FFA and prevent its diagnosis.3,27 Trichoscopy may be a useful tool in differential diagnosis between AGA and FFA, as, in the latter, miniaturized hairs and yellow dots are never present, while erythema and hyperkeratosis perifollicular are typical findings.8 Moreover, the eyebrows, sideburns, and beard may also be involved by FFA, whereas, in AGA, these areas are always spared.

All our patients were Caucasian with an average age of 59±17 years, consistent with the mean age (56±13 years) of patients reported in the literature.3 Arterial hypertension was the most frequent comorbidity as expected, considering its high prevalence (~34%) in the general population. Nevertheless, hypothyroidism is the most common autoimmune disease associated with FFA in women; in men, thyroid anomalies have only been reported in a few cases.3,26 In our study, no patients suffered from hyper- or hypothyroidism, and blood workup results of thyroid hormones and antithyroid antibodies were normal in all cases.

In more than half of our cases, FFA presented with a “zig-zag” pattern. This pattern was described for the first time by Moreno-Arrones et al.29 in female patients as the second most common pattern of presentation of FFA after a linear pattern. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of a zig-zag pattern in male patients. This pattern resembles that of a surgical frontal hairline reconstruction performed in the hair transplant. As is known, the distribution of the aromatase enzyme at the hair follicles is different in men than in women; indeed, the latter have a homogeneous distribution of this enzyme at the frontotemporal hairline, whereas this distribution appears to be heterogeneous due to an alternation of aromatase and 5alpha-reductase in men. For this reason, vellus hairs in women are distributed linearly in the frontotemporal hairline, while, in men, they are less homogenous. As is known, lymphocytic aggression of hair follicles in FFA starts from the ones localized in superficial dermis, such as vellus, vellus-like, and miniaturized follicles,3 so the scarring process involves firstly these types of hair that are mainly located at the anterior part of the hairline. This could be an explanation for the “zig-zag” pattern of presentation.

Eyebrow loss has been reported to occur in about 67% of male patients affected by FFA, while the beard is involved in 55% of male patients26; in our case series, a partial loss of the eyebrows was observed in 37.5% of patients, while the loss of sideburns and beard occurred in 25%. However, consistent with data reported in the literature, eyebrow alopecia in male patients was less severe than that in women with FFA,26 probably due to the longer duration of the anagen phase in men regarding androgen hormones activity. Although facial papules are frequent in male patients,3,26 only one patient presented with them in our case series.

In our case series, signs of concomitant LPP at the scalp but no LP on the skin, mucosae, or nails was observed; also, in the literature, LP has rarely been described in patients with FFA, while LPP seems to be associated with FFA in 28% of cases.

Remarkably, in our case series, a peculiar association never reported before in male patients between FFA and LS was present in two out of eight participants.

LS is an inflammatory chronic disease that mainly affects the ano-genital region in prepuberal children and middle aged female adults30; in male adults, it is rare. The pathogenesis of LS is not completely understood yet; specific human leukocyte antigens (DQ7 and DR12), the family occurrence, and an association with other autoimmune diseases influences the existence of auto-antibodies to an unidentified antigen.30 Some researchers have hypothesized there is a hormonal trigger in the onset of LS, as it is more frequent in postmenopausal women.

An association between FFA and LS has been reported in a few women but not men; as far as we know, our two cases are the first ones in the literature.3,7 The connection between the two pathologies is not clear; in fact, even though the hormonal environment may be a trigger for both FFA and LS, in men, until now, it has not been demonstrated to have any correlation. Recently, serum extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1) antibodies were detected in male LS patients.31 As ECM1 is a glycoprotein that acts as “biological glue” of collagen fibers in the dermis, it has been proposed that antibodies to ECM1 could account for the histopathological abnormalities present in LS.31 ECM1 has been implicated in other fibrotic disorders32 but has not been investigated in FFA yet. However, as ECM1 is expressed in the outer root sheath of hair follicles, it can be assumed that it may represent a target antigen for the immune process in both diseases.

Conclusion

FFA might present with a “zig-zag” pattern as well in male patients, in which it may mimic other types of alopecia, mainly AGA, and trichoscopy is a very important tool for differentiating these two conditions. Importantly, in this report, an association between FFA and LS was described in male patients for the first time. Further studies are needed to establish the extent of this association and to support improved comprehension of the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying these two diseases.

References

- Tolkachjov S, Chaudhry H, Camilleri M, Torgerson R. Frontal fibrosing alopecia among men: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):683–690.e2.

- Stockmeier M, Kunte C, Sander C, Wolff H. Frontale fibrosierende Alopezie Kossard bei einem Mann. Hautarzt. 2002;53(6):409–411.

- Ormaechea-Pérez N, López-Pestaña A, Zubizarreta-Salvador J, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in men: presentations in 12 cases and a review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107(10):836–844.

- Kossard S, Shiell R. Frontal fibrosing alopecia developing after hair transplantation for androgenetic alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(4):321–323.

- Roche M, Walsh M.Y, Armstrong D.K.B. Frontal fibrosing alopecia—occurrence in male and female siblings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2):AB81.

- Nusbaum B, Nusbaum A. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in a man: results of follicular unit test grafting. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(6):959–962.

- Samrao A, Chew A, Price V. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a clinical review of 36 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(6):1296–1300.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Saceda-Corralo D, Bernárdez C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in male patients: a report of 12 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;31(2):e112–e114.

- Ramaswamy P, Mendese G, Goldberg L. Scarring alopecia of the sideburns: a unique presentation of frontal fibrosing alopecia in men. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(9):1095.

- Miteva M, Whiting D, Harries M, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in Black patients. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(1):208–210.

- Chen W, Kigitsidou E, Prucha H, et al. Male frontal fibrosing alopecia with generalised hair loss. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;55(2):e37–e39.

- Stefanato C, Khan S, Fenton D. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lupus overlap in a man: Guilt by association?. Int J Trichology. 2013;5(4):217.

- Dlova N, Goh C, Tosti A. Familial frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(1):220–222.

- Salido-Vallejo R, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Moreno-Gimenez J, Camacho-Martinez F. Beard involvement in a man with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80(6):542.

- Banka N, Mubki T, Bunagan M, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a retrospective clinical review of 62 patients with treatment outcome and long-term follow-up. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(11):1324–1330.

- AlGaadi S, Miteva M, Tosti A. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in a male presenting with sideburn loss. Int J Trichology. 2015;7(2):72.

- Dlova N, Goh C. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in an African man. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(1):81–83.

- Arias-Santiago S, O’Valle F, Husein ElAhmed H, et al. A man with frontal fibrosing alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(2):AB91.

- White F, Callahan S, Kim RH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in a 46-years-old man. Dermatol Online J. 2016; 22(12):13030/qt82h822bg.

- Heppt MV, Letulé V, Laniauskaite I, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a retrospective analysis of 72 patients from a German academic center. Facial Plast Surg. 2017;34(01):088–094.

- Debroy Kidambi A, Dobson K, Holmes S, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in men: an association with facial moisturizers and sunscreens. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(1):260–261.

- Strazzulla L, Avila L, Li X, et al. Prognosis, treatment, and disease outcomes in frontal fibrosing alopecia: a retrospective review of 92 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):203–205.

- Trüeb R, da Silva Libório R. Case report of connubial frontal fibrosing alopecia. Int J Trichology. 2018;10(2):76.

- Lobato-Berezo A, March-Rodríguez A, Deza G, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia after antiandrogen hormonal therapy in a male patient. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(7):e291–e292.

- Brandi N., Starace M., Alessandrini A., et al. First Italian case of frontal fibrosing alopecia in a male. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Feb 4. Epub ahead of print.

- Kanti V, Constantinou A, Reygagne P, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: demographic and clinical characteristics of 490 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(10):1976–1983.

- Peterson E, Gutierrez D, Brinster N, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in males: demographics, clinical profile and treatment experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(2):e101–e104.

- Porriño-Bustamante M, García-Lora E, et al. Familial frontal fibrosing alopecia in two male families. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(9):e178–e180.

- Moreno-Arrones OM, Saceda-Corralo D, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: clinical and prognostic classification. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(10):1739–1745.

- Tran D, Tan X, Macri C, et al. Lichen Sclerosus: An autoimmunopathogenic and genomic enigma with emerging genetic and immune targets. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15(7):1429–1439.

- Edmonds EV, Oyama N, Chan I, et al. Extracellular matrix protein 1 autoantibodies in male genital lichen sclerosus. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(1):218–219.

- Tziotzios C, Stefanato CM, Fenton DA, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: reflections and hypotheses on aetiology and pathogenesis. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25(11):847–852.