J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17(6):13–20.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17(6):13–20.

by Glynis Ablon, MD, FAAD

Dr. Ablon is with the Ablon Skin Institute and Research Center in Manhattan Beach, California.

FUNDING: Funding for this article was provided by Strata Skin Sciences.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the contents of this article.

ABSTRACT: Objective. Photopneumatic devices combine gentle vacuum with pulsed broadband light to treat acne. This seven-week, open-label, single-group study evaluated the efficacy and safety of a photopneumatic device as acne monotherapy.

Methods. Male and female subjects between the ages of 12 and 40 years with any Fitzpatrick Skin Phototype were enrolled (N=30). Subjects had facial acne and a baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 2 (mild) or 3 (moderate), with ≥10 to ≤50 inflammatory lesions, ≥10 but ≤100 non-inflammatory lesions, and ≤1 facial nodule. The primary efficacy endpoints were change in baseline lesion counts and the percentage of subjects achieving a ≥1-grade reduction IGA Score at Day 49. Secondary efficacy endpoints included changes in Acne Quality of Life, self-assessment, and satisfaction scores. Adverse events and tolerability were assessed.

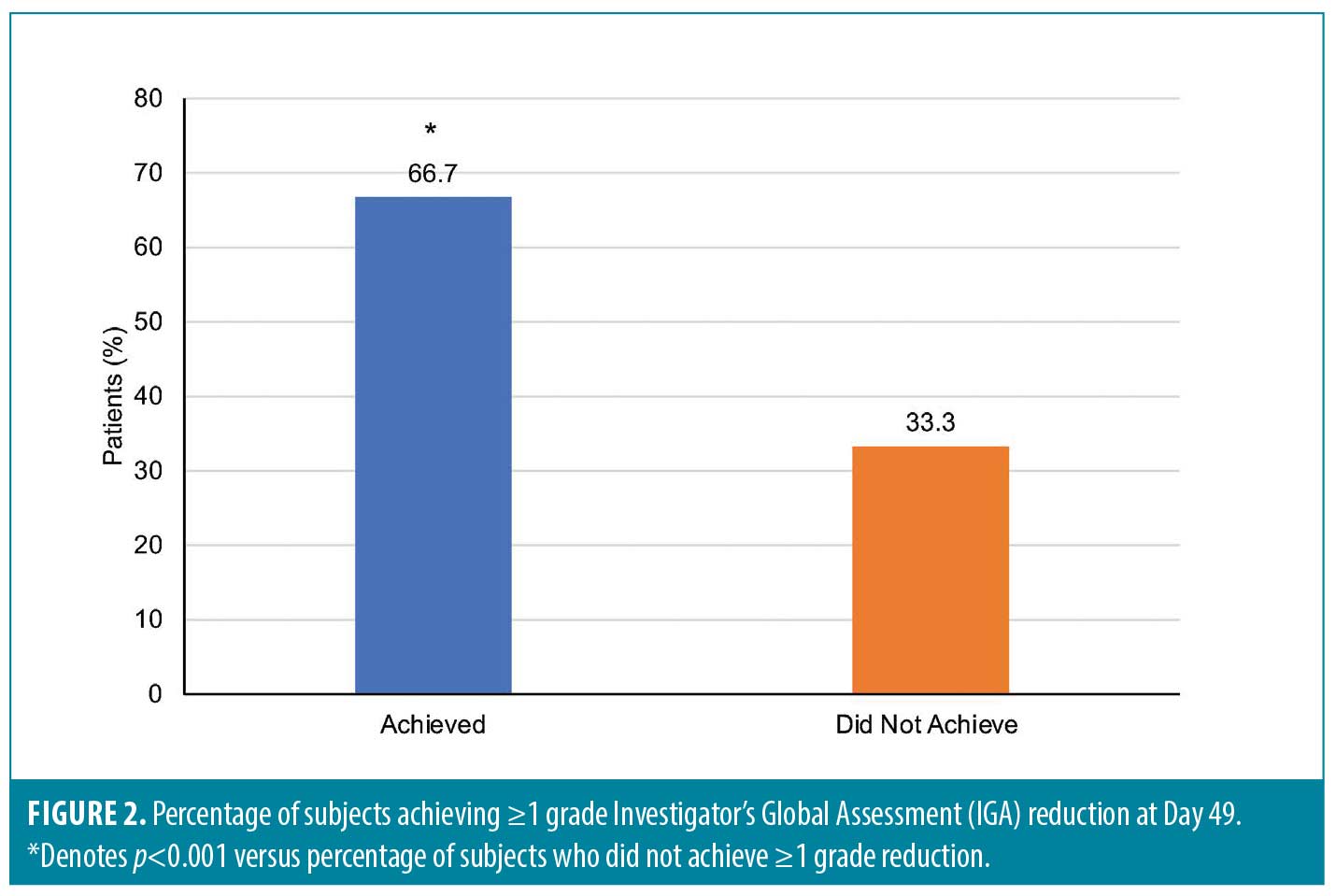

Results. Inflammatory and non-inflammatory lesion counts significantly decreased at all time points versus baseline (for each, p<0.001); IGA scores were improved from baseline at most timepoints and 66.7 percent (20/30) achieved ≥1-grade IGA reduction at Day 49 (p<0.001). Consistent improvements in Acne Self-assessment, Acne-specific Quality of Life, and Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaires were reported. All subjects had favorable investigator and subject tolerability assessments.

Limitations. This study was limited by its small sample size and open-label study design.

Conclusion. Photopneumatic monotherapy significantly reduced acne lesions and resulted in clearer skin in all Fitzpatrick skin types. Adverse events were minor and subject satisfaction was favorable. Customizable energy and vacuum device settings makes the photopneumatic therapy device unique, allowing for a tailored individual approach to treating mild-to-moderate acne.

Clinical Trial Identifier number. NCT06043102 (clinicaltrials.gov).

Keywords: Acne vulgaris, photopneumatic therapy, clinical trial, lesion counts, quality of life

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a common disorder of the pilosebaceous unit. The pathogenesis of acne is complex and involves four primary features: increased sebum gland activity; increased bacterial proliferation, primarily Cutibacterium acnes; abnormal follicular hyperkeratinization and obstruction of the sebaceous follicles; and the release of mediators of inflammation.1 Clinically, these changes result in the inflammatory lesions typically associated with acne, including comedones, pustules, papules, nodules and cysts.1 Although acne vulgaris is commonly associated with adolescence, it also affects older individuals, especially women.2 Unfortunately, even mild forms of acne can be emotionally damaging3 and the risk of delayed treatment includes permanent scarring, which can further affect patient quality of life.4

Due to the multifactorial causes of acne, treatment often includes a combination of therapies, including topical and oral medications, peels, microneedling, and numerous energy-based therapies, including lasers, microdermabrasion, and photodynamic and intense pulsed-light therapy.5,6 While these treatments are very effective for treating some patients, they are not effective for all patients and may be associated with undesirable adverse events (AEs).7,8 Consequently, ongoing research seeks new and improved treatments for acne.

One such treatment involves the use of photopneumatic technology. Devices have been developed that simultaneously combine gentle negative pressure (i.e., vacuum) with broad band pulsed light to target a variety of dermal conditions.9 These devices use vacuum suction to lift target structures in the skin nearer to the surface where they can be targeted with pulsed light. For patients with acne, photopneumatic devices lift the sebaceous gland and turn it outward, emptying its contents of acne-related bacteria, sebum, and dead skin cells.10 Recent studies have shown promising results for treating acne with photopneumatic therapy.11–15

For example, one study assessed the safety and efficacy of a photopneumatic device for treating adult subjects with mild-to-moderate facial acne vulgaris.11 Using a split-faced design, subjects received four treatments at two-week intervals. At three months following the final treatment, subjects achieved overall improvement with significant beneficial effects on the number and severity of acne lesions on the treated side of the face. AEs were mild and transient.

A photopneumatic device is FDA-cleared as a noninvasive, in-office treatment for mild-to-moderate acne, including comedonal, pustular, and inflammatory acne vulgaris (TheraClear®X, Strata Skin Sciences; Horsham, Pennsylvania).16 This treatment is administered through a handheld delivery system that is liquid-cooled for patient comfort and with no downtime. Treatment requires no pre-medication or anesthetic. Treated patients achieved at least 50-percent or greater improvement in lesion counts with a single treatment and increased improvement with ongoing treatments;10 however, the impact of photopneumatic use as monotherapy in patient population of predominately skin of color is unknown. The objective of the following seven-week, open-label, single-group study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TheraClear®X as a stand-alone treatment for mild-to-moderate acne.

Methods

Study subjects. Healthy male and female subjects between the ages of 12 and 40 years and with any Fitzpatrick Skin phototype were eligible for enrollment. Subjects were required to have facial acne and baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scores of 2 (mild) or 3 (moderate) (Supplemental Table 1A) with ≥10 to ≤50 inflammatory lesions (papules, pustules, and nodules), and ≥10 to ≤100 non-inflammatory lesions (open and closed comedones) and no more than one facial nodule.

Subjects using the following medications, products, or therapies agreed to the following pretreatment washout periods: topical facial astringents and abrasives, disallowed facial moisturizers or sunscreens, or acne surgery (1 week); facial antibiotics, antimicrobial soaps, acne drugs, or light therapy (e.g., LED, PDT) (2 weeks); topical anti-inflammatory agents, corticosteroids, retinoids, chemical peels, microdermabrasion, or laser therapy (4 weeks); systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, or other acne treatments (4 weeks); or systemic retinoids (6 months). Each subject expressed their willingness to adhere to all study requirements. Female subjects of childbearing potential further agreed to practice effective contraception for the duration of the study.

Reasons for exclusion included the presence of a facial skin condition that could interfere with clinical evaluations, such as acne conglobata, acne fulminans, secondary acne, perioral dermatitis, clinically significant rosacea, gram-negative folliculitis, dermatitis, or eczema; a history of light-induced seizures or use of photosensitizing medications or supplements, such as tetracycline or St. John’s Wort; skin sensitivity to facial treatments, such as washes or sunscreens; a history of blood coagulation disorders or current use of anticoagulants or blood thinners; a history of keloids or hypertrophic scar formation; active infections, broken skin, or open lesions in the planned treatment area; a history of herpes simplex or connective tissue damage in the planned treatment area; immunosuppressive diseases, systemic lupus erythematosus or porphyria; pregnancy, nursing, or planned pregnancy; use of an investigational drug or device within 30 days of enrollment, or concurrent participation in another research study. Subjects were compensated if they completed all visits. If a subject left the study before completing all visits, they were paid for completed visits.

Study device. The acne treatment system used in this study simultaneously delivers pulsed broadband light from xenon flash lamps in the range of 500nm to 1200nm and up to 3 psi of vacuum within the treatment area (TheraClear®X, Strata Skin Sciences; Horsham, PA).16 The vacuum pulls dermal structures toward the skin surface and withdraws the contents of the follicles.10 The light likely activates porphyrins to destroy Cutibacterium acnes and reduce sebum production.10 The vacuum is released when the process is completed.

The device has adjustable vacuum settings for patient comfort and allows improved treatment of previously challenging facial areas. Three gentle vacuum modes greatly reduce potential for AEs, such as purpura, on sensitive areas such as the forehead, temples, and nose.10 Highly optimized spectral output allows for a single light filter to effectively treat all skin types, including patients with Fitzpatrick Skin Types IV to V.10 The acne treatment system handpiece is continuously cooled for patient safety and provider comfort. As TheraClear®X is an FDA-approved device, the study treatment procedure followed the device Operators Manual.

Study procedures. After an initial screening visit to confirm eligibility (Visit 1), subjects were treated with the Acne Treatment System on Day 0 (Visit 2), and weekly on Days 7, 14, 21, 28 and 35. Subjects returned to clinic on Day 49 (Visit 8) for a final treatment assessment. If no washout of prior medications was required, Visits 1 and 2 activities could occur on the same day. If a washout was needed, Visit 2 occurred after the required washout period. If at Day 7 or thereafter a subject had an IGA Scale score of 0/Clear, no additional Acne System treatments were performed, and the subject proceeded to the end of study visit in two weeks. The treatment was performed by the physician investigator or a trained registered nurse.

Each subject received pre- and post-treatment skincare instructions and was provided with a supply of CeraVe® Hydrating Facial Cleanser, CeraVe® Moisturizing Lotion, and CeraVe® Facial Moisturizing Lotion with SPF 30 (L’Oréal USA; New York, NY) for daily post-treatment care. Subjects cleansed their face each morning with the Hydrating Facial Cleanser followed by an all-over facial application of Facial Moisturizing Lotion with SPF 30. Each evening, subjects cleansed their face with Hydrating Facial Cleanser followed by an all-over facial application of Moisturizing Lotion. Post-treatment, subjects were advised not to wear make-up for 12 to 24 hours and avoid shaving for at least 24 hours.

Study assessments. The IGA Scale (Supplemental Table 1A) was used to assess acne severity and performed prior to the lesion count at Days 0, 7, 14, 21, 35 and 49. Subjects were eligible for enrollment if they had baseline IGA Scale scores of 2 (mild) or 3 (moderate). If at Day 7 or thereafter a subject had an IGA Scale score of 0/Clear, no additional Acne System treatments were performed, and the subject proceeded to the end of study visit in two weeks.

The investigator conducted facial lesion counts at Days 0, 7, 14, 21, 35 and 49.

Investigator’s Tolerability Assessments (Supplemental Table 2A) were performed at Days 0, 7, 14, 21, 35 and 49. Local cutaneous tolerability was assessed by signs of erythema, edema, dryness, scaling, hypo- and hyperpigmentation on the global facial area.

Subject’s tolerability assessments (Supplemental Table 3A) were completed at Days 0, 7, 14, 21, 35 and 49. Local cutaneous tolerability was evaluated by the subject-reported degree of burning, itching, and stinging on the global facial area. The Acne QoL is a health-related quality of life instrument for use in clinical trials to assess the impact of therapy on quality of life among subjects with facial acne.17 The self-administrated questionnaire consisted of 19 questions and was administered at Day 0 and Day 49. The acne self-assessment questionnaire queried subjects about their facial acne and overall facial skin appearance at Day 0 and Day 49. The Acne Subject Satisfaction Questionnaire queried subjects about their treatment satisfaction at Day 49. The Subject Consumer Perception Questionnaire asked subjects a series of questions related to their opinion of what was important to them when choosing an acne treatment at Day 49.

Study endpoints. The primary efficacy endpoints were the change in baseline inflammatory lesion counts, non-inflammatory lesion counts, and percentage of subjects achieving a ≥1-grade reduction in the IGA Score at Day 49 or End of Study (EOS) visit.

The secondary efficacy endpoints were the change in baseline Acne QoL questionnaire scores, Acne Self-assessment questionnaire scores, Acne Subject Satisfaction questionnaire scores, and Subject Consumer Perception questionnaire at Day 49 or EOS visit.

The safety endpoints included the nature, severity, and frequency of adverse events (AEs) and the local cutaneous tolerability of the Acne Treatment System. Tolerability assessments during the study included an Investigator’s Tolerability Assessment (erythema, edema, dryness, scaling, hypo- and hyperpigmentation) with each potential symptom rated from 0 for none to 3 for severe, and Subject Tolerability Self-Assessment (itching, burning, and stinging).

Statistical analysis. The required sample size for this study was estimated using a mixed model method19 and related software.19 It was determined that a sample size of 30 subjects would have a minimum power of 80 percent to detect a medium effect size with a p-value of 0.01. Data were analyzed from all randomized subjects who had a baseline and at least one post-baseline assessment. Chi-square and descriptive analyses were also used. A drop-out rate of less than 15 percent after the baseline assessment but prior to the last post-baseline assessment was expected and was accounted for in the power analyses. All statistical tests were two-tailed. Data were analyzed using commercial software (SPSS® Statistics 28.0, IBM® Corporation; Armonk, New York).

Ethics. The protocol and related materials used in this study were reviewed and approved by a commercial institutional review board (Advarra® IRB Services; Columbia, Maryland). Each subject provided written informed consent prior to participating in any study-related activities. The conduct of this study followed all applicable guidelines for the protection of human subjects research as outlined in United States FDA 21 CFR Part 50,20 in accordance with the accepted standards for Good Clinical Practices,21 and the standard practices of Ablon Skin Institute and Research Center. Subjects also provided signed Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and Photography Releases for digital imaging of the entire face at all visits was obtained. Subjects could be withdrawn or elect to withdraw from the study at any time for revocation of consent, AEs which could endanger the well-being of the subject, non-adherence or protocol violation, or a new medical condition or illness which could affect their safety or invalidate the results of the study. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06043102.

Results

Thirty subjects completed the study; baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Subjects were otherwi se healthy adolescents and young adults with a mean age of 22 years. Most were female (63%), White (83%), and Hispanic (70%) with Fitzpatrick Skin Types I to VI but most being II to IV (86%).

se healthy adolescents and young adults with a mean age of 22 years. Most were female (63%), White (83%), and Hispanic (70%) with Fitzpatrick Skin Types I to VI but most being II to IV (86%).

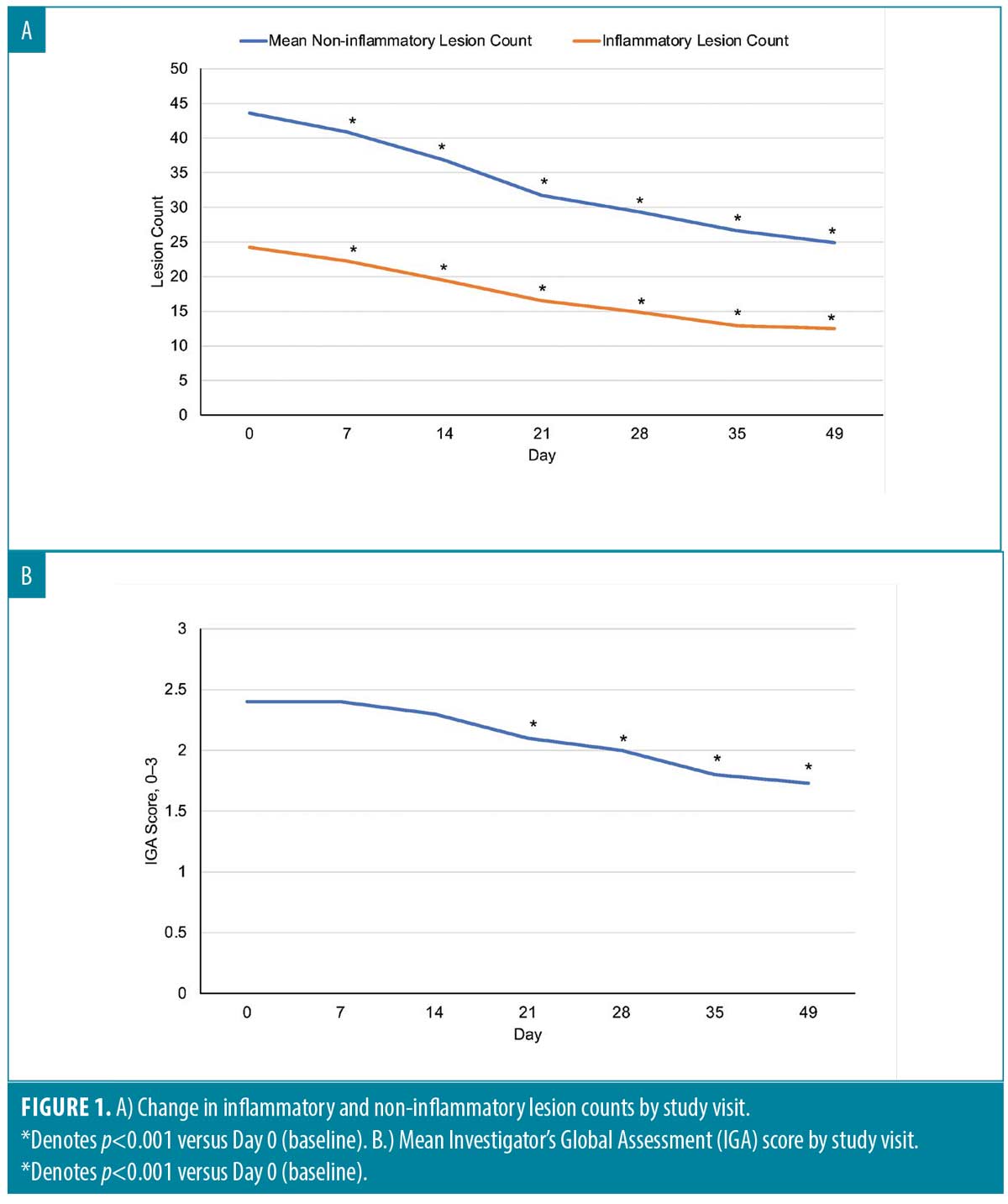

Efficacy. Acne lesion counts and IGA Scores. Changes in inflammatory and non-inflammatory lesion counts are shown in Figure 1A. Statistically significant reductions in lesion counts were observed at each time point (p<0.001) compared with Day 0. Baseline nodule counts were small and did not change. Reductions in lesion counts were seen in all Fitzpatrick Skin types.

Significant improvement in IGA scores was observed at most post-baseline time points compared with Day 0 (for each, p<0.001) with the exception of Day 7 and Day 14 (Figure 1b). Two-thirds (20/30) of subjects achieved ≥1 grade IGA reduction at Day 49 (p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Acne self-assessment questionnaire. The Acne Self-Assessment Questionnaire revealed consistent improvement in all self-assessment responses. Facial acne ratings were improved by 31.3 percent, and other improvements included skin texture (34.7%), overall facial skin appearance (31.4%), facial oiliness (27.5%), pore size (23.5%), and facial redness (22.6%) (Table 2).

Acne-specific quality of life questionnaire (Acne QoL). Improvements in all aspects in QoL were improved at Day 49 and the extent of improvements ranged from 28.6 to 53.8 percent. Subjects were no longer annoyed spending time daily cleaning and treating the face because of acne (53.8%), concerned about facial scarring (49.4%), meeting new people (49.0%), socializing with people (47.7%), and going out in public (45.4%) (Table 3).

Acne subject treatment satisfaction questionnaire. Day 49 Acne Subject Satisfaction Questionnaire scores revealed, 80 percent of subjects were satisfied or very satisfied with this treatment and 86.7 percent would recommend it to a friend (Table 4).

Subject consumer perception questionnaire.Results of the Subject Consumer Perception Questionnaire indicated subjects were very likely or somewhat likely to choose this treatment based on ease of treatment (duration, frequency, comfort) 83.3 percent. Subjects were very likely or somewhat likely to choose treatment based on overall improvement in skin appearance 83.3 percent and overall side effects compared to other acne treatments 66.7 percent (Table 5).

Safety. Favorable investigator and subject tolerability assessments were reported for all subjects. Investigator reports of mild erythema and hyperpigmentation at baseline (Day 0) and Day 49 were similar with a slight increase in dryness at Day 49 (n=3 vs. n=4). Subject tolerability self-assessments revealed one subject with mild itching at Day 49. An unrelated AE of herpes simplex was reported at Day 21.

Investigator’s tolerability assessment.Mean Investigator’s Tolerability Assessment scores are shown in Table 6. The lowest mean scores were for edema and itching (0), and highest were for erythema (0.83 on Day 7) and hyperpigmentation (0.93 on Days 0 to 49).

Subject’s tolerability self-assessment. Subject’s Tolerability Self-assessments revealed one report of mild stinging at Day 7 (0.5%).

Discussion

Photopneumatic therapy is a unique noninvasive, in-office acne treatment system that combines gentle vacuum with pulsed broadband light technology. When the activated TheraClear®X device is placed on the treatment area, the applied vacuum draws sebaceous glands of acne-affected skin to the skin surface. It withdraws sebaceous material which is then exposed to intense 500nm to 1200nm pulsed broadband light. Exposure to light activates porphyrins which destroy Cutibacterium acnes and reduce sebum production.10 Treatment is administered through a liquid-cooled, handheld system that delivers comfortable treatment of mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris with no downtime.16 Histological studies have clearly demonstrated the application of photopneumatic therapy results in the mechanical extrusion of pilosebaceous units, with subsequent thermal injury and decreased sebaceous gland activity.22 The result is rapid improvement of inflammatory and non-inflammatory acne lesions.

This study sought to evaluate the efficacy and safety of six weekly TheraClear®X sessions as a stand-alone treatment for mild-to-moderate acne in healthy subjects of all skin types. Overall, significant reductions in lesion counts were observed; IGA scores were improved and statistically significant at most baseline timepoints versus Day 0, suggesting visible improvements are seen as early as after three treatments. Two-thirds (20/30) of subjects achieved the primary efficacy endpoint, which was the percentage of subjects with at least a 1-grade IGA improvement at Day 49 (p<0.001).

Skin clarity appeared to improve in all subjects based on self-assessments. In addition, Investigator’s and Subject’s Tolerability Self Assessments agreed that the treatment was well-tolerated with no treatment-related adverse events. These results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the safety and efficacy of photopneumatic therapy for treating mild-to-moderate acne.12,13,23

Noninvasive treatments for acne such as photopneumatic therapy may be well-suited for treating patients for whom first-line therapies such as topical treatments are ineffective, poorly tolerated or contraindicated.5 TheraClear®X was specifically designed and FDA-cleared for the treatment of mild-to-moderate acne, including comedonal, pustular, and inflammatory acne vulgaris.24 TheraClear®X also permits the administration of maintenance treatments for occasional acne outbreaks for maintaining clear skin. The device also permits customized treatment with variable vacuum and energy settings.24

Conclusion

Photopneumatic monotherapy significantly reduced facial acne lesions and fostered clearer skin in all Fitzpatrick Skin types, while providing a high degree of subject satisfaction. The ability to customize energy and vacuum device settings to tailor treatment to individual patient needs is beneficial. Photopneumatic therapy is a viable option for whom other acne treatment options are ineffective or poorly tolerated.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Strata Skin Sciences, Horsham, PA. The author acknowledges the editorial assistance of Carl S. Hornfeldt, PhD, RPh of Apothekon, Inc. in Woodbury, Minnesota, and Martina Cartwright, PhD, RD of Beacon Science Inc., in Phoenix, Arizona, during the preparation of this manuscript, with funding provided by Strata Skin Sciences.

References

- Sutaria AH, Masood S, Saleh HM, et al. Acne Vulgaris. In: Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459173. Accessed: August 22, 2023.

- Collier CN, Harper JC, Cafardi JA, et al. The prevalence of acne in adults 20 years and older. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):56–59.

- Marron SE, Chernyshov PV, Tomas-Aragones L. Quality-of-life research in acne vulgaris: Current status and future directions. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(4):527–538.

- Gieler U, Gieler T, Kupfer JP. Acne and quality of life – impact and management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:12–14.

- Fabi SG, Beleznay K, Berson DS, et al. Treatment of acne in the aesthetic patient: A round table update. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22(9):2391–2398.

- Eichenfield DZ, Sprague J, Eichenfield LF. Management of acne vulgaris: A review. JAMA. 2021;326(20):2055–2067.

- Bagatin E, Costa CS. The use of isotretinoin for acne – an update on optimal dosing, surveillance, and adverse effects. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(8):885–897.

- Mirza HN, Mirza FN, Khatri KA. Outcomes and adverse effects of ablative vs nonablative lasers for skin resurfacing: A systematic review of 1093 patients. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(1):e14432.

- Rajabi-Estarabadi A, Choragudi S, Camacho I, et al. Effectiveness of photopneumatic technology: a descriptive review of the literature. Lasers Med Sci. 2018;33(8):1631–1637.

- Munavalli G. Photopneumatic technology for the treatment of mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris—A review. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2023;16(5):S4–S6.

- Lee EJ, Lim HK, Shin MK, et al. An open-label, split-face trial evaluating efficacy and safety of photopneumatic therapy for the treatment of acne. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24(3):280–286.

- Shamban AT, Enokibori M, Narurkar V, et al. Photopneumatic technology for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(2):139–145.

- Gold M, Biron J. Treatment of acne with pneumatic energy and broadband light. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(7):639–642.

- Wanitphakdeedecha R, Tanzi EL, Alster TS. Photopneumatic therapy for the treatment of acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(3):239–241.

- Politi Y, Levi A, Enk CD, et al. Integrated cooling-vacuum-assisted 1540-nm erbium:glass laser is effective in treating mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(9):2389–2393.

- TheraClear®X. Strata Skin Sciences, Horsham, PA. Available: http://theraclearx.com. Accessed August 21, 2023.

- Fehnel SE, McLeod LD, Brandman J, et al. Responsiveness of the Acne-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (Acne-QoL) to treatment for acne vulgaris in placebo-controlled clinical trials. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(8):809–816.

- Hedeker D, Gibbons R, Waternaux C. Sample size estimation for longitudinal designs with attrition: Comparing time-related contrasts between two groups. J Educ Behav Stat. 1999;24:70–93.

- Hedeker D. Selected materials on Longitudinal Data Analysis. Available: http://tigger.uic.edu/%7Ehedeker/rmass2.exe. Accessed: August 23, 2023.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, June 2023. Available: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRsearch.cfm?CFRPart=50. Accessed: August 19, 2023.

- International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline, Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R1) 1996. Available: http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6/E6_R1_Guideline.pdf. Accessed: October 19, 2022.

- Omi T, Munavalli GS, Kawana S, et al. Ultrastructural evidence for thermal injury to pilosebaceous units during the treatment of acne using photopneumatic (PPX) therapy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10(1):7–11.

- Gold MH, Biron J. Efficacy of a novel combination of pneumatic energy and broadband light for the treatment of acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(7):639–642.

- Bhatia A, Burgess CM, Munavalli GS, et al. Photopneumatic technology for the treatment of mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris-expert perspectives. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16:S7–11.