J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(12):E74–E83.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(12):E74–E83.

by Leena Amiri, MD; Hassan Galadari, MD; Fadwa Al Mugaddam, MPH; Abdul Kader Souid, MD; Emmanuel Stip, MD, MSc, FRCP; and Syed Fahad Javaid, MBBS, MSc, MRCPsych

Dr. Amiri, Ms. Mugaddam, Dr. Stip, and Mr. Javaid are with the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the College of Medicine and Health Sciences at United Arab Emirates University in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Dr. Galadari is with the Department of Internal Medicine at the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Dr. Souid is with the Department of Pediatrics at the College of Medicine and Health Sciences at United Arab Emirates University in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Dr. Stip is also with the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Montréal in Montréal, Canada.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. In the past decade, there has been an increase in the number of cosmetic procedures performed globally. About one-third of individuals who undergo cosmetic procedures are under the age of 35. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has become a regional hub for cosmetic procedures. This cross-sectional study examines the perception of cosmetic procedures among youth in the UAE. Methods. A 63-question survey was electronically disseminated to university students to identify factors associated with the use of cosmetic procedures in this population. Results. Ninety-one percent of the 178 participants were female, and 58 percent of them were aged 19 to 21. The majority of the participants felt cosmetic procedures are gaining acceptance in UAE society. Nearly 70 percent of participants felt that a legal and regulatory framework was important to determine the permissible age for undergoing cosmetic surgeries. Limitations. One limitation of the study lies in a modest response rate of 35.6 percent. There was a small number of male responders, and the assessment of differences between sex was not easy to conduct. Conclusion. Cosmetic procedures are increasingly being accepted among youth in the Middle East, with skin and nasal procedures being the most popular. The youth’s concept of ideal body shape is in alignment with the Western ideas of beauty. Future research could characterize these perceptions in other cultures and explore differences in what is perceived to be beautiful in various parts of the world.

Keywords: Body image, cosmetic procedures, plastic surgery, youth, United Arab Emirates, Middle East

Beauty is difficult to define. It is an enigma that fascinated the ancient Greeks, influencing their mythology.1 Beauty is not just a visual experience; rather, it entails the qualities that give pleasure, meaning, or satisfaction to the senses.2 Traditionally, it has been accepted that the canons of beauty vary from one civilization to another. In the West, a woman considered “socially beautiful” is “very thin and often slightly tanned, her nose is small and her forehead large.”3 This contrasts with the concept of beauty held by the hunter-gatherers from the Hadza tribe of Tanzania, living apart from civilization, who preferred curvy body shapes.4 The search for beauty does not have to be guided by the quest for objective perfection. In today’s world, beauty has become a tool to improve the quality of life in general, a means of surpassing the physical and relational problems of an individual.5 It is sought after by both sexes and is not limited to a specific age group.

Cosmetic procedures contend with the preservation, rejuvenation, or enhancement of the physical appearance through surgical and/or therapeutic interventions. In the past decade alone, there has been a surge in the number of cosmetic procedures performed globally.6

There is paucity of research exploring cosmetic procedures in the Middle East. A study from 2017 identified laser hair removal, botulinum toxin injection, liposuction, filler, and scar revision as common procedures among women, while rhinoplasty was the most common procedure among men.7

The United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) population is made up of a heterogeneous group of different nationalities. According to one estimate, UAE ranks third in the Middle Eastern region in terms of customers undergoing cosmetic procedures, after Saudi Arabia and Egypt.8 Dubai has been called the Middle East’s “plastic surgery hub,” with a reported 236 licensed plastic surgeons, 386 licensed dermatologists, and 277 facilities in 2018.8

The demand for cosmetic procedures in the UAE has been on the rise, with cosmetic surgery among top five procedures of health tourism.9,10 The aesthetics industry is one of the most important contributors of medical tourism in the UAE. This can be attributed to a significant increase in the number of regional patients as well as a surge in internationally trained industry professionals based in the region. The number of plastic surgeons per capita in Dubai is among the highest in the world.11

In the United States of America, home of the largest cosmetic industry in the world, the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS) has recorded over eight million cosmetic procedures performed in 2003, representing a three-fold increase in just five years; this steep increase has continued further in the last decade.12 Almost half of all patients who undergo cosmetic procedures are between the ages of 35 and 50, and about 30 percent of them are under the age of 35.12 Recently, there has been an increase in the number of adolescents undergoing these procedures as well. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) revealed that 230,000 cosmetic procedures were performed on individuals younger than 18 years old in 2011; this statistic represented a 16-fold increase in the number of procedures performed on adolescents compared to 1996.13 Most of the cosmetic procedures were nonsurgical in nature and comprised laser hair removal, chemical peeling, micro-dermabrasion, and botulinum injections.13

The factor that drive the younger population to consider cosmetic procedures have yet to be fully delineated. A Dutch study revealed that body image and attitudes toward physical appearance improve as teenagers grow older, regardless of whether they undergo cosmetic interventions.14 This suggests that vulnerable adolescents might seek cosmetic procedures, which they might later regret or deem unnecessary. Reality television shows pertaining to cosmetic procedures can foment misconceptions about the indications, risks, and benefits of cosmetic procedures.15 A British study found that female participants with poor self-esteem, poor life satisfaction, low self-rated attractiveness, and who were heavy watchers of television were more likely to undergo cosmetic procedures.16 Psychiatric conditions, such as body dysmorphic disorder, are known to increase the likelihood of individuals seeking cosmetic procedures.17 A desire to boost self-confidence is now as important as improving the aesthetics of sagging skin, according to a commercial survey of nearly 8,000 women assessing the evolving beauty needs of women around the world.18

With a focus on the Middle Eastern population, one study sought to assess the attitudes and acceptance of cosmetic procedures among individuals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The study revealed that while nearly 70 percent of participants agreed that cosmetic procedures could help individuals feel better about themselves, about 27 percent disagreed.19 Another survey of Saudi Arabian women revealed that improving self-esteem was the most common motive for undergoing a cosmetic procedure and that wearing a veil is no barrier in seeking cosmetic treatment.20 Factors such as the influence of media, the perception of the ideal human form, and the professionalism and high standard of cosmetic surgery in the UAE have been identified as contributing to the surge of cosmetic procedures being performed in the UAE.21

There has been an observed interest in cosmetic surgery in the Arab world overall, and the UAE is no exception. The number of cosmetic surgery and dermatology clinics have been steadily increasing with what seems to be a secured population. These clinics have attracted both sexes and patients of varying ages, and it has been observed that younger people have become more interested in these procedures. We have observed adolescents who come in with their parents. These factors have led to our interest in exploring the motivations of this young population to undergo these procedures and discover whether they have common factors in their profile. The present study seeks to improve our awareness of the cultural perceptions of beauty, personal views of cosmetic procedures, personal experiences, and the society’s perception of cosmetic procedures in the UAE. To our knowledge, this is the first systematized description of this population. We report a description of the attitudes as an exploratory approach to generate further hypothesis.

Methods

A structured questionnaire was disseminated online to university students in the UAE in 2017. The survey was designed to evaluate the attitudes of youths pertaining to cosmetic procedures and, if applicable, to delineate their personal experiences of undergoing these procedures. A cosmetic procedure was defined as any intervention that involved cosmetic correction and/or alteration of existing body features. It also included minimally invasive procedures, such as botulinum toxin injections and fillers, as well as major surgical procedures, such as liposuction, rhinoplasty, and breast augmentation.

Participants were informed about the nature of the study, and confidentiality was assured. The online, self-administered questionnaire included 63 questions (Survey Questionnaire-Supplementary). This study leveraged convenience sampling, as it was inexpensive, efficient, and simple to implement.22 Ethical approval was granted by the United Arab Emirates University Division of Research and Graduate Studies Ethics Committee.

The 63 questions of the questionnaire spanned five domains. The first domain contended with participants’ demographic details, such as age, sex, educational level, nationality, occupation, financial status, marital status, and place of study. This was followed by questions exploring participants’ personal views of cosmetic procedures. We evaluated the specific types of interventions that participants considered cosmetic procedures, such as their views of beauty and the ideal human form by body part (i.e., face shape, body shape, eye shape, skin colour, eye colour, nose shape, nose size, lip size, hair type, hair length, etc.). The questions appraised the opinions of participants regarding cosmetic procedures, the level of support they would render a friend who was keen on a cosmetic procedure, and what age group the participants thought cosmetic procedures would likely be performed on.

The next section explored participants’ personal experiences with cosmetic procedures and the means of payment for such procedures. We asked about the level of satisfaction after the procedure, plans for cosmetic procedures, and the impact of these procedures on the participants’ self-esteem and confidence.

The fourth part of the questionnaire contended with the attitudes of participants’ direct family members. The questions in this section evaluated the parents’ views on cosmetic procedures, history of cosmetic procedures in the family, and the participants’ own opinions about their family members’ cosmetic procedures, if applicable.

The final part of the questionnaire pertained to participants’ views of the UAE society’s attitudes towards cosmetic procedures. The questions explored participants’ views on young men and women in the UAE who underwent cosmetic procedures, participants’ knowledge of alternatives to cosmetic procedures, and the impact of such procedures on the likelihood of getting married. The questions also explored participants’ views regarding the legal oversight necessary for cosmetic procedures and the concept of parental consent in relation to age group.

These answers were collated online and tabulated using Microsoft Excel for ease of analysis.

Results

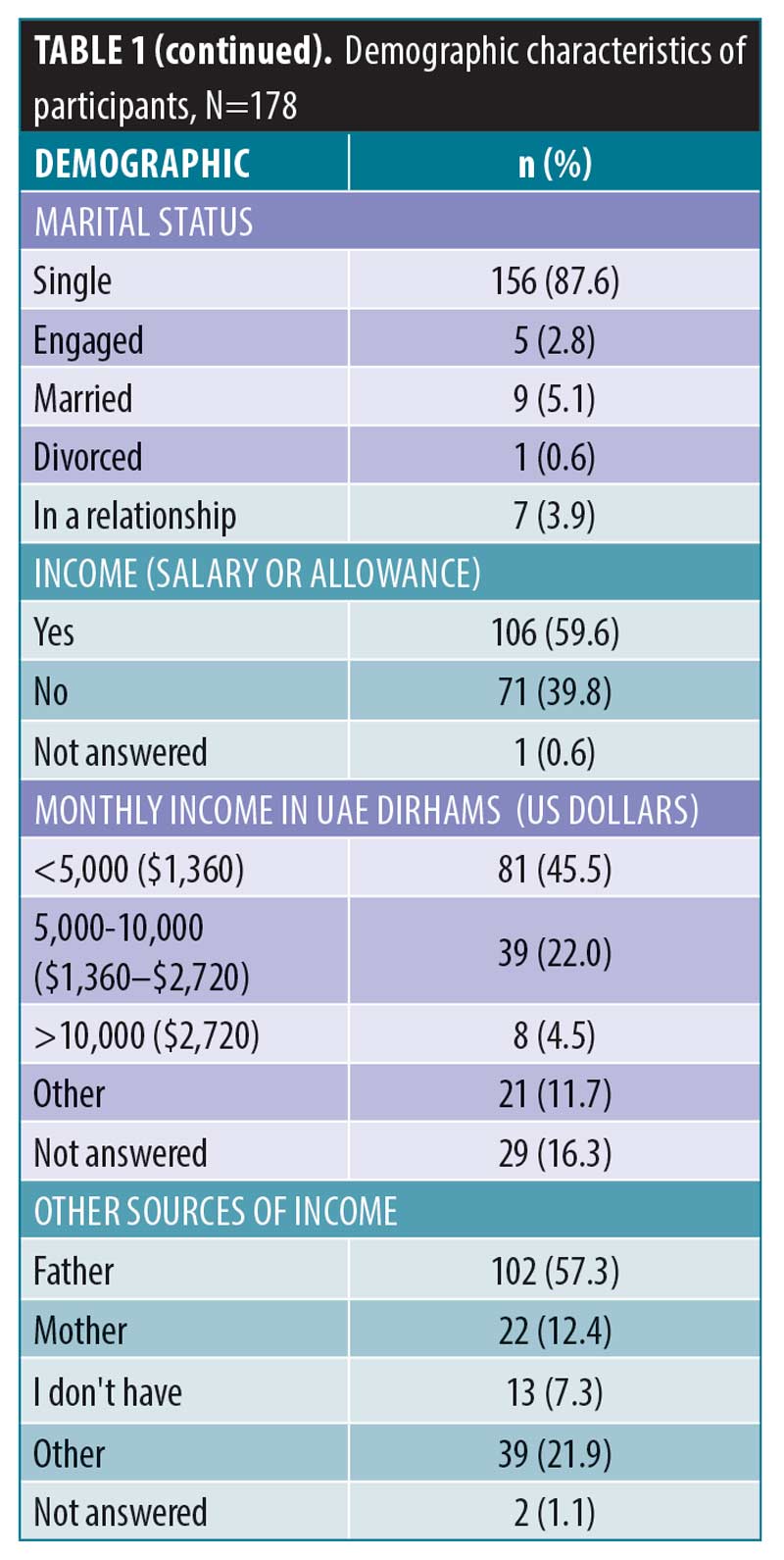

The results of the study will be introduced on a domain-by-domain basis. There were five sections of the questionnaire, and 500 questionnaires were sent out electronically. Only 178 participants (35.6%) responded to the online survey. The majority (58.4%) of participants were between 19 and 21 years of age. The vast majority (91%) of participants were female, and nearly 90 percent of all participants were UAE nationals. About 88 percent of participants were single, and nearly 60 percent of them reported receiving an allowance. About 73 percent of participants identified their father’s monthly income as more than 10,000 UAE Dirhams (about $2,700 USD). Nearly 48 percent of the respondents’ mothers had a minimum of university level education. The intricacies of these demographic details can be referenced in Tables 1 and 2.

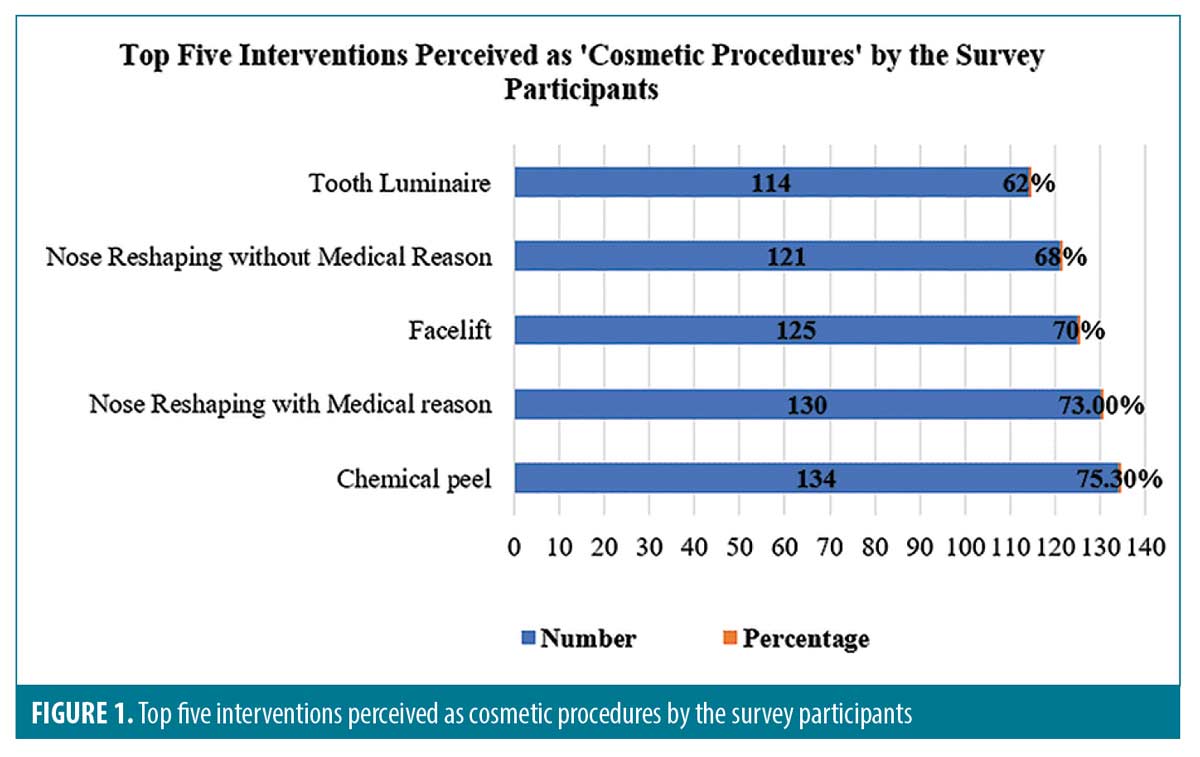

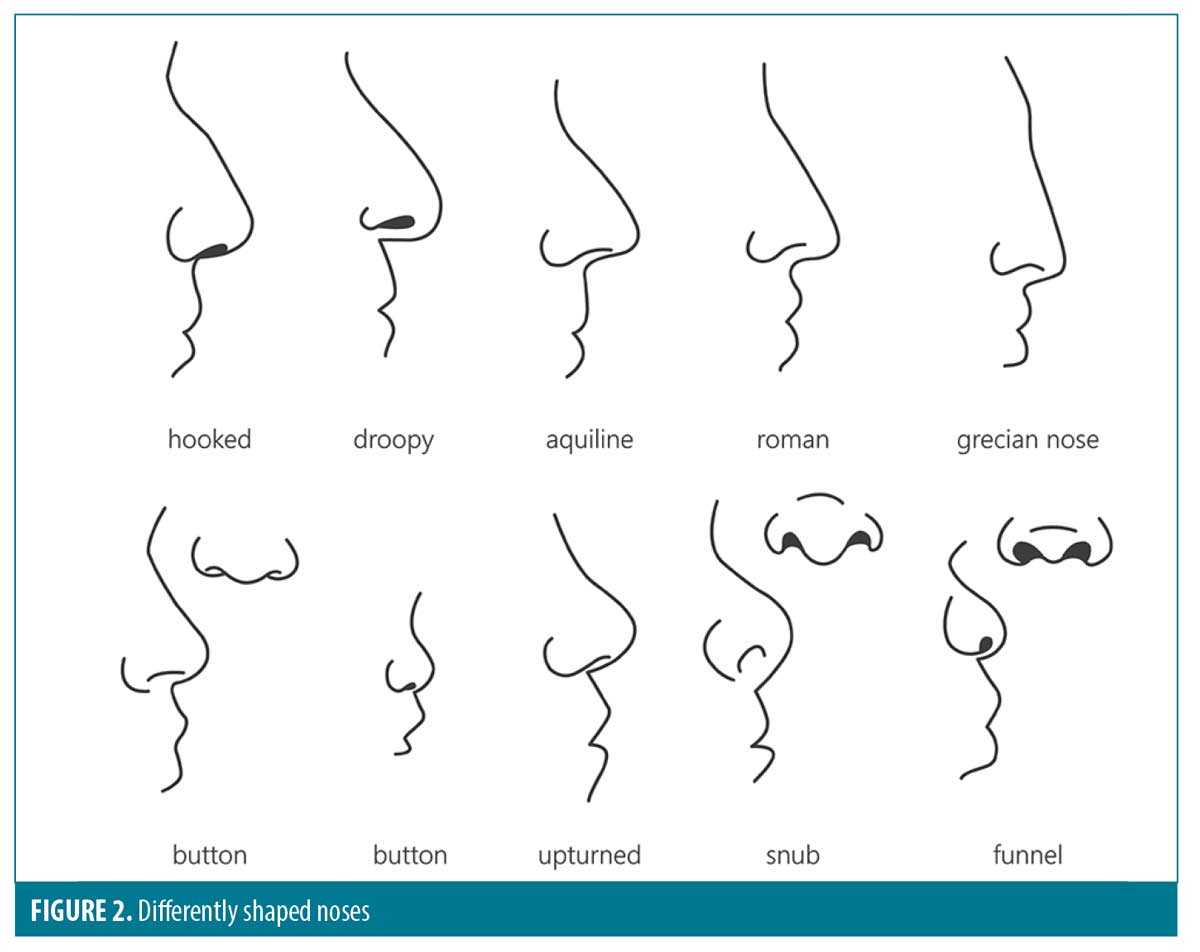

In the second domain, several insights were identified regarding participants’ views on cosmetic procedures. About 39 percent of the participants had no opinion on cosmetic procedures, whereas 27.5 percent of them did not support cosmetic procedures. Conversely, 32.6 percent of participants either strongly supported or conditionally supported cosmetic procedures. The survey asked the respondents to identify which procedures (out of 17 choices) they considered “cosmetic” in nature. The results are depicted in Figure 1. This section also explored participants’ perceptions of the ideal body shape and human form. The majority (65.2%) of participants responded that the hourglass body shape is the most beautiful, and nearly 34 percent of participants felt that an oval and heart shaped face was the most beautiful, respectively. About 66 percent of participants indicated that pale white and light skin were the most beautiful complexions. Only 1.7 percent of participants viewed a “hooked nose” as attractive. The drawings used to describe various types of nasal shapes can be seen in Figure 2.23 More details pertaining to their perceptions can be referenced in Table 3.

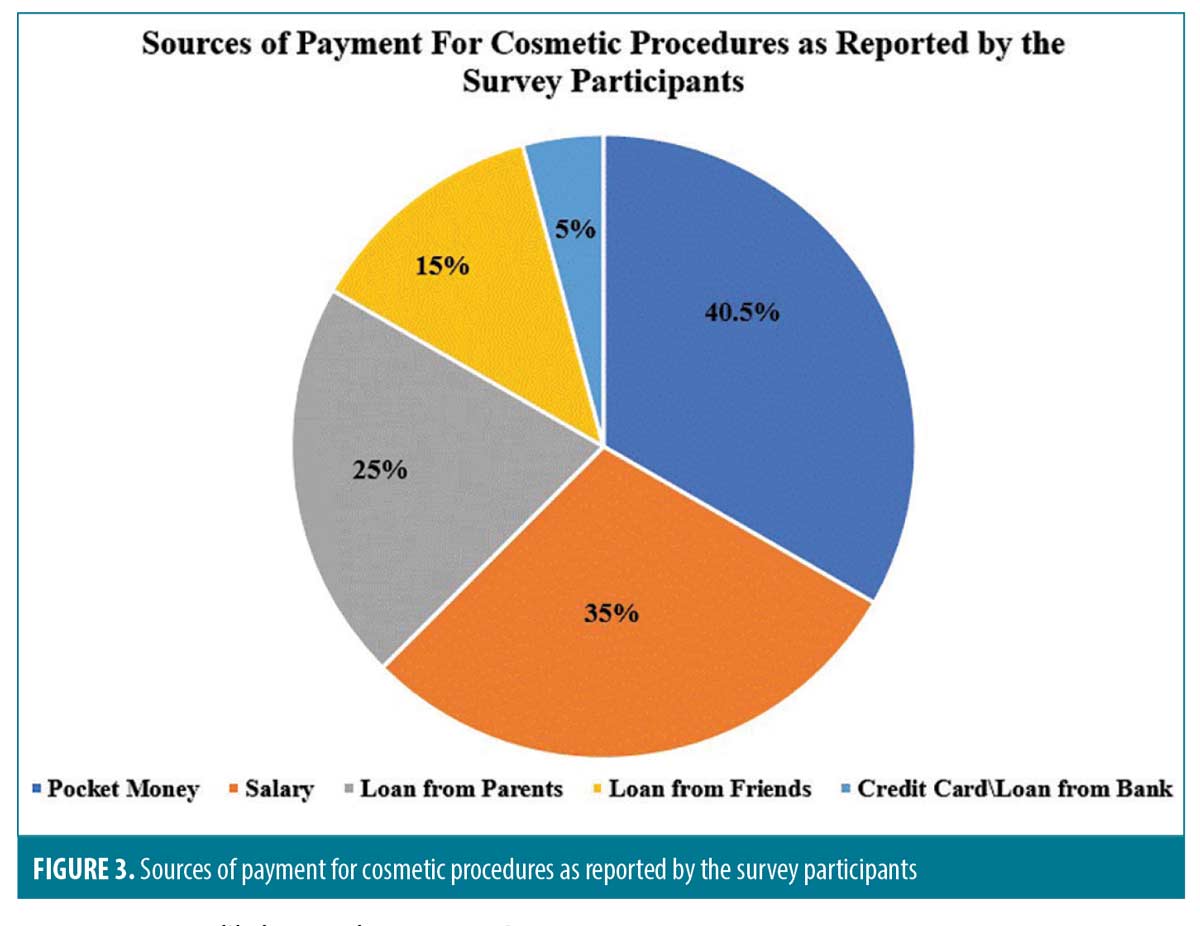

For Section 3, participants’ personal experiences with cosmetic procedures were explored. Most (86.6%) participants had never undergone a cosmetic procedure. Of those participants, the majority (46.8%) would not consider having any performed in the future. Of the participants that had a cosmetic procedure performed (n=20), only one person had five or more procedures; the remaining 19 had undergone 1 to 4 procedures. The procedures were financed by various means as depicted in Figure 3. Out of the 20 individuals who had undergone a cosmetic procedure, 13 (65%) participants expressed satisfaction with the result of the procedure. However, 45 percent of the participants who had previous cosmetic procedures felt that the it had no impact on their confidence contrary to the 40 percent who felt that it boosted their confidence.

Participants were asked about their parents’ views on cosmetic procedures. Only 3.4 percent felt that their parents would be supportive of it, while nearly 35 percent stated that their parents were against cosmetic procedures. About 17 percent of participants believed that their parents would not allow them to have cosmetic procedures mainly due to those being unnecessary or because of religious reasons. These details can be referenced in Table 4.

For the final section of the questionnaire, participants’ views of the societal attitudes in the UAE towards cosmetic procedures were evaluated. Fifty-nine percent of participants thought that there were viable alternatives to cosmetic procedures, such as makeup. Nearly 63 percent of total participants felt that cosmetic procedures are acceptable or slowly becoming acceptable to the society. However, 20 percent of participants felt that UAE culture frowned upon cosmetic procedures. There was a clear difference in opinion about the society’s view of cosmetic procedures in men compared to in women. Nearly 48 percent of participants felt men who had undergone a cosmetic procedure were frowned upon in the UAE culture as opposed to only 10.7 percent in the case of women. Ninety-nine (55.6%) participants felt that people do not discuss these procedures openly, and 47 (26.4%) of them felt that knowledge of them having undergone such procedures would decrease their chances of getting married. Of the total participants, 122 (68.5%) felt that there should be legal regulation of the permissible age for individuals undergoing cosmetic procedures, and 125 (70.2%) of them felt that parental consent should be mandatory for individuals younger than 20 years old. Detailed questions in this section can be referenced in Table 5.

Discussion

The increasing demand for cosmetic procedures in younger individuals recently has been linked to media portrayals, a reduction in stigma, and higher levels of disposable income.24 Cosmetic surgery is slowly becoming more acceptable in the UAE despite the country’s conservative views that are influenced by the religious perception of cosmetic interventions.25

Surgical procedures, such as cleft lip repair, have been identified to increase confidence and quality of life.26 There is limited evidence on the benefits of cosmetic surgeries, such as liposuction, on a person’s overall psychological health.27

Previous studies have examined patient satisfaction with cosmetic procedures.28 Studies focusing on attitudes concerning cosmetic surgery have mostly been carried out in Western nations. Therefore, this study aimed to retrieve insights from within the United Arab Emirates, which given the heterogeneity of its population, can be representative of the Middle East.

Personal views of cosmetic procedures. This study confirms the trend of increasing acceptance for cosmetic procedures among young participants. Ng and colleagues stress that although cosmetic procedures have become more prevalent in the younger population in recent years, there is limited research on the topic from an Asian perspective.13

This study asked participants to reveal their views of cosmetic procedures performed on individuals of their age group. Most had a positive view of cosmetic procedures, with many seeing this as a matter of personal choice and freedom. Among the participants against cosmetic procedures, lack of regulations and religious reasons were cited with some outlining that “we live in a horrible world based on society beauty standards” and “I am against plastic surgery just because this changes Allah’s creation. This is Haram.” Many participants felt that the decision was justified for medical reasons, while very few were in favour of having a cosmetic procedure at a young age. Others stated that social media negatively influences people’s self-perception. This viewpoint is in agreement with available evidence on the impact of social media on the acceptability of cosmetic procedures among youth. Chen and colleagues found that those who invested more in social media had a positive association with the possibility of having cosmetic procedures.29

Cultural perception of beauty. Many studies have focused on a scientific perspective of the human body, but anthropology has created an analytical view that situates the body as social practice rather than an object.30 From this perspective, it is beneficial to view the body as a reflection for society, and vice versa, that is always changing and evolving.30 This viewpoint recognizes that individuals consider the human body as an area of change to affect social connections and cultural and personal cosmologies. Techniques and habits related to beauty, such as cosmetic procedures, are produced and constructed by culture. Therefore, there is a relational connection between the two.31

The concept of beauty, the ideal face, and body form is often shaped by the media via advertisements, subliminal messages, and social media.32 It has been argued that this is due to years of over-sexualization and sexism, which have shaped the actions of mostly female consumers.33 Many women with naturally dark complexion believe that fair skin makes them more appealing, attractive, and successful, suggesting that skin-whitening products relate to primal instincts.34 The present study has identified similar findings, with a vast majority of participants choosing the “pale white” and “aight” skin colors as the most attractive as per the Fitzpatrick scale.35 The “dark brown” skin color was selected by just 3.4 percent as the most beautiful. This viewpoint is likely intertwined with societal constructs, with a link between fair skin and privilege.34 Evidence has found that women get their skin lightened with the belief that it will increase their position in society, their identity, and the likelihood of being employed and getting married.36

Participants in the current study preferred the hourglass figure with a low waist to hip ratio, which has also been identified in Western research.37 The research by Neyret et al37 revealed that a low waist to hip ratio and a low body mass index (BMI) is currently perceived as the most attractive female body, whereas a high BMI and a low waist to chest ratio is currently perceived as most attractive in men among Western society. This finding emphasizes that the concept of beauty is shifting towards a more Westernized ideal within the UAE. Middle Eastern beauty icons are not often discussed or focused on within the media and societal discussion. A study of more than 5,000 models throughout 12 countries revealed that editorial decisions within magazines were dominated by European and North American beauty ideals.38

Our study found that a small number of participants viewed a “hooked nose” as attractive. A hook or hump is a characteristic of the “Arabic nose,” which is long, slightly hooked, and with a pendant dip.31 It is seen as a negative facial feature, making women worried that they will not get married if they do not modify their facial features.31

In Middle Eastern culture, beauty is generally recognized by an oval or round face; temple fullness; pronounced, elevated, arched eyebrows; large almond-shaped eyes; well-defined, laterally full cheeks; a small, straight nose; full lips; a well-defined jawline; and a prominent, pointed chin.39 The results from this survey give us insight into prevalent concepts of beauty among the youth in the UAE. The results showed little change from documented, cultural perception of beauty in the Middle East. The perception of facial beauty is highly individual.40 This information can potentially help professionals devise cosmetic treatment strategies that reflect current trends in the UAE’s young population.

UAE society’s perception of cosmetic procedures. Generational differences in perspective is a common feature of any viable, progressive society. The results from this survey arguably indicate an intergenerational shift in attitude towards cosmetic procedures in the UAE. A portion of study participants stated that their family’s views were dependent upon the reason for having the procedure, suggesting that their parents may be open to the idea of cosmetic procedures under certain circumstances. These situations could be investigated further to gain insight. Those who stated that their parents did not allow them to have a cosmetic procedure revealed that their reasoning was based on religion or the belief that it was unnecessary. This correlated with the finding that 44.4 percent of participants were unable to think of a direct family member who had a cosmetic procedure carried out.

Change in societal attitudes is a slow but continuous process. As we appraise the changing views about cosmetic procedures globally, it would seem that society is pushing individuals towards changing their appearance cosmetically. A recent societal agenda to “fix” the body can be seen within cosmetic procedures’ medical jargon in areas like Brazil.40 Cosmetic procedures have been offered that “correct the negroid nose,” which is deeply based on a cultural bias.40 When jargon is used about correcting the broken or “wrong,” it conditions society to a specific characteristic of beauty.38

About a quarter of study participants felt that they would have a reduced likelihood of getting married if others were aware that they had undergone cosmetic procedures. This finding suggests that cosmetic procedures are in demand, but individuals prefer it to remain a private matter. In contrast, Al Kuttab9 argued that cosmetic surgery used to be viewed as a private matter, with people usually embarrassed or reluctant to reveal their procedures, whereas individuals now admit it as a fashion statement, showing wealth and status.9

We asked the participants about their perception of the society’s view on cosmetic procedures. Nearly 56 percent stated that it was slowly becoming acceptable. This was followed by a similar question but focusing on men having undergone cosmetic procedures. Only 21.9 percent of participants stated that it was slowly becoming acceptable. This survey has revealed that likelihood of men being judged and frowned upon for undergoing cosmetic procedures is much higher than women undergoing similar procedures. This finding could suggest that the stereotypical ideology of man is still focused on in the Middle Eastern society. It is arguably related to the traditional notion of the role men have had in the society and the cultural concept of beauty. However, this sample may not be representative of the wider society. The shift from traditional masculinity has been explained by post-industrial work pattern changes, ideologies of technology consumption, and a change in gender relations.41

Experience of cosmetic procedures among youth in the Middle East. Our study found that only 40 percent of participants who underwent cosmetic procedures reported a positive change in their confidence levels. This finding is in contrast with previous evidence linking cosmetic procedures with enhanced self-esteem and patient confidence levels.42 Asimakopoulou et al43 reported a significant increase in post-surgery satisfaction levels in women who underwent breast augmentation procedures.

The above results show cosmetic procedures’ lack of impact on participants’ self-confidence. This becomes even more interesting when seen in the context of a reasonably high satisfaction level with the procedures themselves (65% of the relevant participants). This potentially highlights the need for further research into motivations and reasons behind a decision to undergo a cosmetic procedure. The Tripartite Influence Model suggests that there are both indirect and direct sources of body dissatisfaction leading to a decision to have cosmetic procedures.44 These include parents, peers, and the media. Comparing beauty ideals within cultural stereotypes can also have an indirect impact.44 In addition, self-objectification and negative attitudes towards age, beauty, body size, shape, fat phobia, and the belief that breast appearance is more important than their function, are all linked to body dissatisfaction.44 Lastly, there is the argument that women are stigmatized by the expectation beauty.33 It becomes a prominent train of thought, as it is continuously negatively reinforced by both direct and indirect sources.33 The ideology of gender and how it is construed within society facilitates this focus. The man is often seen as a spectator, whereas the woman as a spectacle.7 This perspective is in line with Goffman’s idea of stigma.45

Limitations. One limitation of the study lies in the response rate of 35.6 percent. Some limitations of this qualitative study are also revealed when comparing the results of this study to the available literature on factors that motivate individuals to undergo cosmetic procedures. There is a small number of respondents who were male, and the assessment of difference between gender is not easy to conduct. This is relevant, as women are more likely to undergo cosmetic procedures as compared to men.46,47 This work is a preliminary description of our findings and allows multiple hypotheses to be tested in future projects involving this population like the relationship between individual’s income, parents’ education, family opinion on cosmetic procedures, and the likelihood of undergoing a cosmetic procedure. The authors recommend statistical analysis performed in future studies to delineate correlations or likelihood ratios to support or test these notions.

Conclusion

Cosmetic procedures are increasingly being accepted among youth in the Middle East. This can be attributed to the promulgation of cosmetic surgery related media and increased accessibility, affordability, and quality of cosmetic procedures in recent years. More research is needed in exploring cosmetic procedures in the Middle East, including the specific effects of social media and celebrity role models. There is still a dearth of research in regard to the ideal human form and perceptions of what constitutes beauty. Future research could characterize these perceptions in other cultures and explore differences in what is perceived to be beautiful in various parts of the world.

References

- Tambone V, Barone M, Cogliandro A, et al. How you become who you are: a new concept of beauty for plastic surgery. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42(5):517–520.

- Corbett JR. What is Beauty? Ulster Med J. 2009;78(2):84–89.

- Nahoum-Grappe V. Souffrir pour être belle. Une invitation à l’ethnologie de la mondialisation esthétique (Commentaire). Sci Soc Sante. 2004;22:35–39.

- Marlowe F, Wetsman A. Preferred waist-to-hip ratio and ecology. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30:481–489.

- Mousavi SR. The ethics of aesthetic surgery. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(1):38–40.

- Swami V, Chamorro-Premuzic T, Bridges S, Furnham A. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: personality and individual difference predictors. Body Image. 2009;6(1):7-13

- Alharethy SE. Trends and demographic characteristics of Saudi cosmetic surgery patients. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(7):738–41.

- Tajmeeli releases original data about growing cosmetic surgery market in the Arab World. Tajmeeli. https://tajmeeli.com/en/tajmeeli-annual-survey-data/. Accessed 7 Dec 2020.

- Kuttab JA. Plastic surgery on the rise in UAE. Khaleej Times. https://www.khaleejtimes.com/nation/uae-health/plastic-surgery-on-the-rise-in-uae. Accessed 4 Dec 2020.

- Plastic surgery among top five procedures of health tourism in Dubai. Gulf News. https://gulfnews.com/uae/health/plastic-surgery-among-top-five-procedures-of-health-tourism-in-dubai-1.2175202. Accessed 7 Dec 2020.

- Cosmetic and plastic surgery boom in the UAE. Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation. https://wedc.org/export/market-intelligence/posts/cosmetic-and-plastic-surgery-boom-in-the-uae/. Accessed 4 Dec 2020.

- Sarwer DB, Cash TF, Magee L, et al. Female college students and cosmetic surgery: an investigation of experiences, attitudes, and body image. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(3):931–938.

- Ng JH, Yeak S, Phoon N, Lo S. Cosmetic procedures among youths: a survey of junior college and medical students in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2014;55(8):422-6.

- Simis KJ, Hovius SE, de Beaufort ID, et al. After plastic surgery: adolescent-reported appearance ratings and appearance-related burdens in patient and general population groups. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(1):9–17.

- Crockett RJ, Pruzinsky T, Persing JA. The influence of plastic surgery “reality TV” on cosmetic surgery patient expectations and decision making. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(1):316–324.

- Furnham A, Levitas J. Factors that motivate people to undergo cosmetic surgery. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:47–50.

- Crerand CE, Franklin ME, Sarwer DB. Body dysmorphic disorder and cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7):167–80.

- New global research uncovers changed attitude to beauty as women seek confidence over youth. Asia Research Magazine website. https://asia-research.net/new-global-research-uncovers-new-attitude-beauty-women-seek-confidence-youth. Accessed 4 Dec 2020.

- Morait SA, Abuhaimed MA, Alharbi MS, et al. Attitudes and acceptance of the Saudi population toward cosmetic surgeries in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(5):1685-90.

- Al-Natour SH. Motives for cosmetic procedures in Saudi women. Skinmed. 2014;12(3):150–153.

- Alnaqbi M. Cosmetic surgery in the UAE. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mariam_Alnaqbi4/publication/331345440_Cosmetic_Surgery_in_the_UAE/links/5c74f1f5a6fdcc47159c0ce5/Cosmetic-Surgery-in-the-UAE.pdf. Accessed 7 Dec 2020.

- Jager J, Putnick DL, Bornstein MH. More than just convenient: the scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2017;82(2):13–30.

- Lazuin. Differently shaped noses. Adobe Stock. https://stock.adobe.com/uk/images/differently-shaped-noses/139987030. Accessed 9 Dec 2020.

- Javo IM, Sørlie T. Psychosocial predictors of an interest in cosmetic surgery among young Norwegian women: a population-based study. Plast Surg Nurs. 2010;30(3):180–186.

- Atiyeh BS, Kadry M, Hayek SN, Moucharafieh RS. Aesthetic surgery and religion: Islamic law perspective. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32(1):1–10.

- Lefebvre A, Munro I. The role of psychiatry in a craniofacial team. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61(4):564–569.

- Geliebter A, Krawitz E, Ungredda T, et al. Physiological and psychological changes following liposuction of large volumes of fat in overweight and obese women. J Diabetes Obes. 2015;2(4):1–7.

- Clapham PJ, Pushman AG, Chung KC. A systematic review of applying patient satisfaction outcomes in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(6):1826–1833.

- Chen J, Ishii M, Bater KL, et al. Association between the use of social media and photograph editing applications, self-esteem, and cosmetic surgery acceptance. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019;21(5):361–367.

- Chrisler J. Leaks, lumps and lines: stigma and women’s bodies. Pscyh of Women Quart. 2011;1:1–13.

- Levine M. Perception of Beauty. London: Intech;2017:178.

- Mills J, Shannon A, Hogue J. Beauty, Body Image and the Media. London: Intech; 2016:145–153.

- Greenfield S. When Beauty is the Beast: The Effects of Beauty Propaganda on Female Consumers. Nebraska: University of Nebraska, 2018:1–3.

- Apuke O. Why Do women bleach? Understanding the rationale behind skin bleaching and the influence of the media in promoting skin bleaching: a narrative review. Glob Media J. 2017;16:15–18.

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(6):869–871.

- Yetunde M. Use of Skin Lightening Creams. BMJ. 2010;341:6202.

- Neyret S, Bellido Rivas AI, Navarro X, Slater M. Which body would you like to have? The impact of embodied perspective on body perception and body evaluation in immersive virtual reality. Front Robot AI. 2020;7:31.

- Yan Y, Bissell K. The globalization of beauty: How is ideal beauty influenced by globally published fashion and beauty magazines? J Intercult Commun Res. 2014; 43(3):194–214.

- Kashmar M, Alsufyani MA, Ghalamkarpour F, et al. Consensus opinions on facial beauty and implications for aesthetic treatment in Middle Eastern women. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7(4):e2220.

- Riggs L. The Globalisation of Cosmetic Surgery: Examining BRIC and Beyond. Uni of San Fran. 2012;33:1-5.

- Kachel S, Steffens MC, Niedlich C. Traditional masculinity and femininity: validation of a new scale assessing gender roles. Front Psychol. 2016;7:956.

- Borujeni LA, Pourmotabed S, Abdoli Z, et al. A comparative analysis of patients’ quality of life, body image and self-confidence before and after aesthetic rhinoplasty surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020;44(2):483-490.

- Asimakopoulou E, Zavrides H, Askitis T. Plastic surgery on body image, body satisfaction and self-esteem. Acta Chir Plast. 2020;61(1-4):3-9.

- Huxley C, Halliwell E, Clarke V. An examination of the tripartite influence model of body image: does women’s sexual identity make a difference? Psych of Women Quart. 2014;39:337-348.

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London: Penguin Books;1990:1–4.

- Delinsky SS. Cosmetic Surgery: A Common and Accepted Form of Self-Improvement? J Appl Soc Psychol. 2005;35(10):2012–2028.

- Brown A, Furnham A, Glanville L, Swami V. Factors that affect the likelihood of undergoing cosmetic surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2007;27(5):501–508.