J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(7):E53-E59.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(7):E53-E59.

by James Q. Del Rosso, DO; Sandra Marchese Johnson, MD; Todd Schlesinger, MD; Lawrence Green, MD; Nestor Sanchez, MD; Edward Lain, MD; Zoe Draelos, MD; Jean-Philippe York, PhD; and Rajeev Chavda, MD

Dr. Del Rosso is with JDR Dermatology Research in Las Vegas, Nevada and Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery Clinical Research in Maitland. Florida. Dr. Johnson is with Johnson Dermatology in Fort Smith, Arkansas. Dr. Schlesinger is with the Clinical Research Center of the Carolinas in Charleston, South Carolina. Dr. Green is with the George Washington School of Medicine in Washington D.C. Dr. Sanchez is with Dermatology and Pathology, at Aibonito Hospital in Aibonito, Puerto Rico. Dr. Lain is with the Austin Institute for Clinical Research in Austin, Texas. Dr. Draelos is with Dermatology Consulting Services, PLLC in High Point, North Carolina. Dr. York is with Galderma Laboratories, LP in Fort Worth, Texas, and Galderma SA in Switzerland. Dr. Chavda is with Galderma SA in Switzerland.

FUNDING: This study was funded by Galderma R&D.

DISCLOSURES: James Del Rosso has acted as a research investigator, consultant and/or speaker for Almirall, Bausch Health (Ortho Dermatology), BiopharmX, Cassiopea, EPI Health, Galderma, JEM Health, La Roche Posay, LEO Pharma, Mayne Pharma, Sol-Gel, Sonoma, Sun Pharma, and Vyne Therapeutics (Foamix); Sandra Marchese Johnson has been advisor or speaker for Nielsen, Amgen, Allergan, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, and Candela, and an investigator for Arcutis, Aurigene, Amgen, Regeneron, Galderma, Nielsen, Dermavant, Lilly, Therapeutics, GSK, Aclaris, Foamix, Novartis, Abbvie, Gage, Cassiopea, National Psoriasis Foundation, University of Pennsylvania; Todd Schlesinger has received equipment/research funding from AbbVie/Allergan, Acrutis, Almirall, Anterios, AOBiome, Astellas Pharma US, Athenex, Biofrontera, Biorasi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Brickell Biotech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cara Therapeutics, Castle Biosciences, Celgene, Centocor Ortho Biotech (Now Janssen Biotech), ChemoCentryx, Coherus Biosciences, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Corrona, Cutanea Life Sciences, Dermavant, Dermira, DT Pharmacy & DT Collagen, Lilly, EPI Health, Galderma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kiniksa, Leo, Merz, Nestle Skin Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Sisaf and Trevi, and has acted as in consulting, speaking or advisory capacity for AbbVie, Allergan, Almirall, Amgen, Bioderma, Biofrontera AG, BioPharmx, Bristol Myers Squibb, Castle Biosciences, Celgene, CMS Aesthetics DCME, DUSA/Sun Pharma, Lilly, EPI Health, Foundation for Research and Education in Dermatology (FRED), Galderma, Greenway Therapeutix, Kintor, MED Learning Group, Merz, MJH Associates, Nextphase Therapeutics, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pharmatecture, Pierre Fabre, Plasmed, Prolacta Bioscience, Regeneron, Remedly, Inc, Sanofi Genzyme, SkinCeuticals/L’Oreal, SUN Pharma, UCB and Verrica; Lawrence Green has served as consultant, investigator or speaker for Almirall, Cassiopea, Galderma, Ortho-Derm, Sol-Gel, SunPharma, and Vyne; Nestor Sanchez has acted as consultant for Galderma; Edward Lain has performed research, consulted, and/or was a member of a speaker bureau for Galderma, Bausch Health, Valeant, Ortho Dermatologics, Novartis, Dr Reddy’s, Sol Gel, Vyne, Almirall, Actavis, Cassiopea, and Dermira; Zoe Draelos received a grant from Galderma to function as a research site for the acne project; Jean Phillipe York and Rajeev Chavda are employees of Galderma.

ABSTRACT: Objective. We evaluated the efficacy and safety of trifarotene plus oral doxycycline in acne.

Methods. This was a randomized (2:1 ratio) 12-week, double-blind study of once-daily trifarotene cream 50µg/g plus enteric-coated doxycycline 120mg (T+D) versus trifarotene vehicle and doxycycline placebo (V+P). Patients were aged 12 years or older with severe facial acne (≥20 inflammatory lesions, 30 to 120 non-inflammatory lesions, and ≤4 nodules). Efficacy outcomes included change from baseline in lesion counts and success (score of 0/1 with ≥2 grade improvement) on investigator global assessment (IGA). Safety was assessed by adverse events and local tolerability.

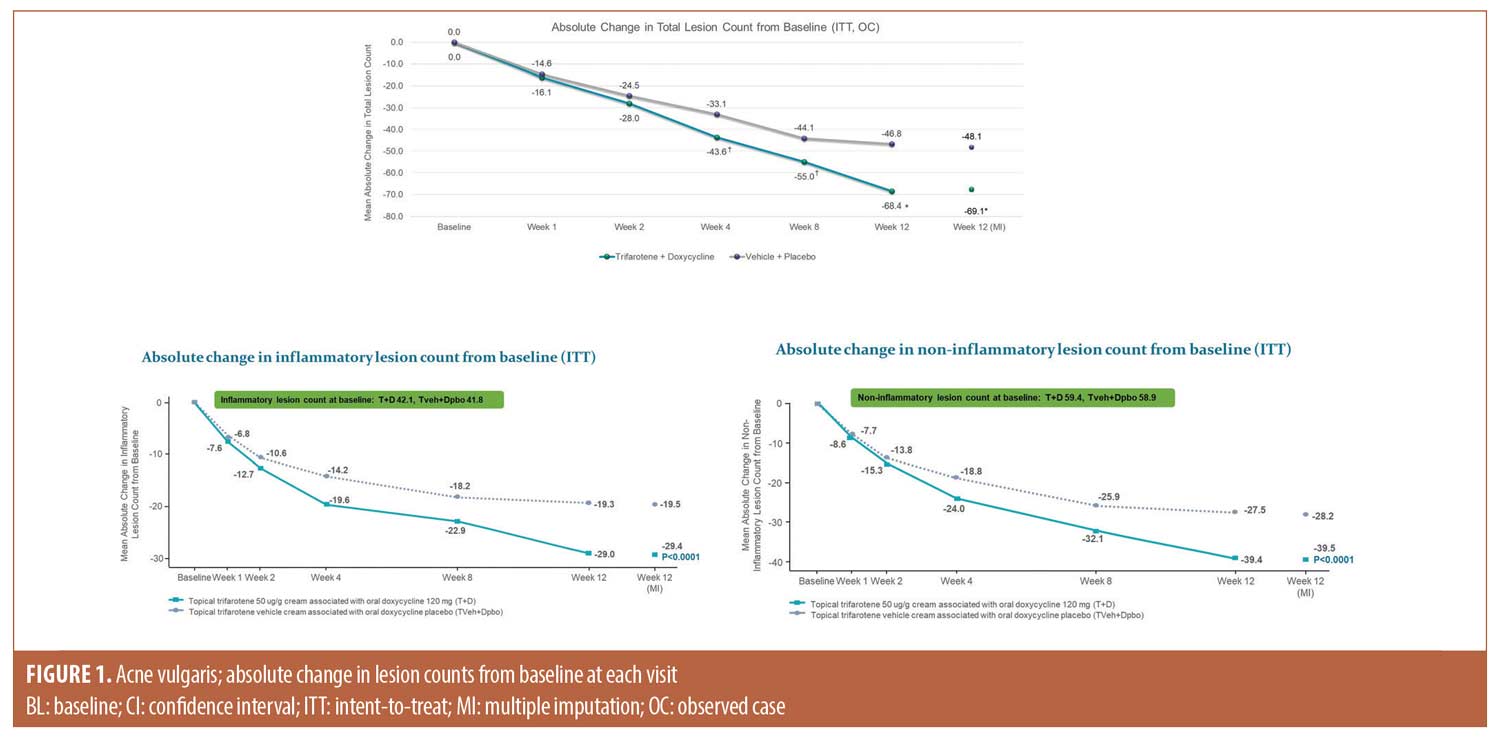

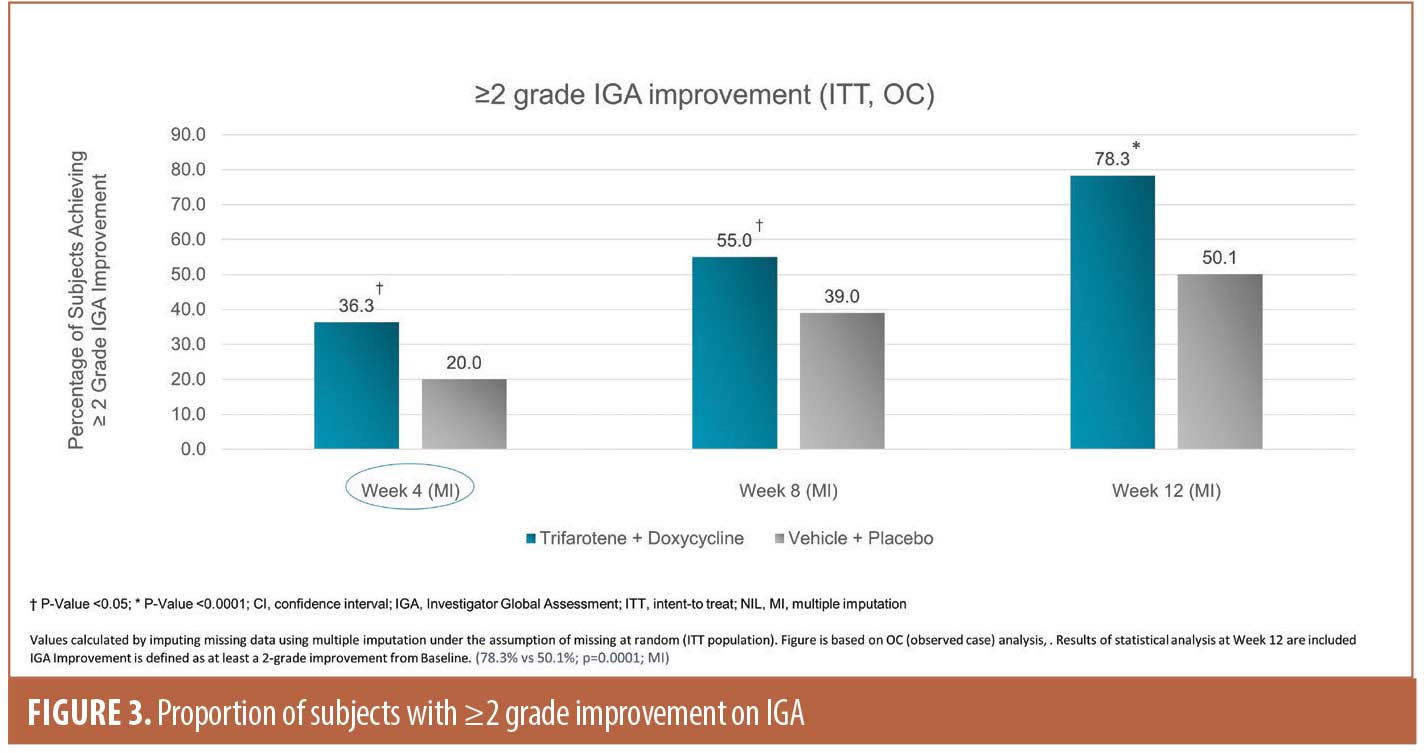

Results. The study enrolled 133 subjects in the T+D group and 69 subjects in the V+P group. The population was balanced, with an approximately even ratio of adolescent (12–17 years) and adult (≥18 years) subjects. The absolute change in lesion counts from baseline were: -69.1 T+D versus -48.1 V+P for total lesions, -29.4 T+D versus -19.5 V+P for inflammatory lesions, and -39.5 T+D versus -28.2 for non-inflammatory lesions (P<0.0001 for all). Success was achieved by 31.7 percent of subjects in the T+D group versus 15.8 percent in the V+P group (P=0.0107). The safety and tolerability profiles were comparable between the T+D and V+P arms.

Conclusion. T+D was demonstrated to be safe and efficacious as a treatment option for patients with severe acne.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris, trifarotene, doxycycline, combination therapy, severe acne

Acne vulgaris, a common inflammatory skin disease, has a multifactorial pathogenesis that centers on the pilosebaceous unit.1,2 Severe acne can have a significant negative impact on the quality of life of patients.3 Furthermore, any severity of acne can result in long lasting scarring, a risk that tends to increase as disease severity worsens.4-8 Current treatment options for severe acne are relatively limited, and often start with a combination therapy regimen involving topical retinoids and/or benzoyl peroxide with an oral antibiotic.9–12 Oral isotretinoin (OI) is an effective option, but is not always appropriate due to contraindications or because the patient does not wish to take isotretinoin.13,14 Additionally, even if OI treatment is elected, initiation of treatment may be substantially delayed (e.g., due to iPledge requirements or time of year), necessitating an interim treatment plan. Thus, there is a need for expanded medical options for patients with severe acne.

Trifarotene cream 50µg/g, highly selective for the retinoic acid receptor (RAR)-γ (the most common RAR subtype in the skin), is approved for the treatment of acne. Two large-scale Phase III trials involving a total of 2,420 patients with moderate acne showed trifarotene monotherapy achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) success (clear/almost clear plus at least 2-grade improvement) rates of 42.3 percent and 29.4 percent by study endpoint at Week 12 (P<0.001 vs. vehicle).15 Lesion counts were significantly reduced compared to placebo (P<0.001), with statistical separation from placebo as early as Week 1.15 A 52-week study (n=453) showed trifarotene has good safety and tolerability, with adverse events that occurred in approximately 10 percent of subjects, usually in the first three months of therapy, were mostly cutaneous, and were non-serious.16

Oral antibiotics are frequently prescribed to treat severe acne and are recommended by acne treatment guidelines, with the precaution to limit the period of treatment to the minimum necessary to reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance. Doxycycline, particularly in the enteric-coated formulation, has a long track record of safety in acne management.17,18 Doxycycline has an overall favorable efficacy and safety profile; however, current acne recommendations suggest limiting duration of use to minimize risks for antimicrobial resistance.1,17,19

The current randomized, placebo-controlled, Phase IV study was designed to provide information about the efficacy and safety of trifarotene plus doxycycline in comparison to vehicle/placebo in patients with severe facial acne.

Methods

Study design. This was a multicenter, 12-week, double blind study of once-daily trifarotene cream 50µg/g plus enteric coated doxycycline 120mg (T+D) or trifarotene vehicle plus doxycycline placebo (V+P) with 2:1 randomization. The protocol, informed consent form, and other written material provided to subjects and any additional relevant study documentation were submitted to WCG IRB (Princeton, New Jersey) and approval was obtained before the study was initiated. This clinical study was conducted in accordance with the protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki, and the International Conference on Harmonization/Good Clinical Practice. All subjects who participated in the study were fully informed and provided written informed consent (parent/guardian in the case of minors). There was one amendment to the protocol which permitted enrollment of subjects with four or less nodules or cysts (combined), gave a more specific definition of total lesion counts to align with prior acne studies, and included clarity for reporting effects attributable to the wearing of face masks (i.e., maskne). The study start date was July 28, 2020 and the study completion date was April 30, 2021.

Determination of sample size. At least 198 subjects aged 12 and older were to be randomized, with an approximate even distribution of male to female subjects, and adult (≥18 years) and adolescent subjects (12–17 years). The study had 80 percent power to detect a difference of -15 in absolute change from baseline of total lesions count between T+D and V+P with a two-sided type I error of 0.05, assuming a common standard deviation of 32.5 and a proportion of drop-outs and non-evaluable subjects around 15 percent.

Randomization and blinding. Upon signature of the informed consent form, each subject was assigned a Subject Identification Number (SIN) to be used throughout the study. Upon confirmation of subject eligibility, the Interactive Response Technology (IRT) was used to assign the blinded study drug (T+D or V+P). The randomization code ensured the treatment assignment was random and was allocated in an overall 2:1 ratio active/active (T+D) to placebo/placebo (V+P). Randomization was performed by Advanced Clinical, the contract research organization.

The study site staff and subjects were blinded to study treatment throughout the study. Members of the site staff did not have access to the randomized treatment assignment. Active topical and oral study medications had similar appearance, packaging, and use instructions as the corresponding vehicle or placebo.

Washout periods and application instructions.Washout periods were pre-specified in the protocol as follows: two weeks for topical treatments and wax epilation, one week for aesthetic procedures, and four weeks for dermatologic procedures, such as photodynamic therapy, laser therapy, and deep chemical peeling. Additional washout periods included four weeks for systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, or spironolactone; and 12 weeks for oral retinoids/isotretinoin, cyproterone acetate, and immunomodulators. Patients were prohibited from using these medications during the study period. Instruction was provided regarding application of the study drug as well as cleansing and moisturizing practices. Subjects were provided with skin care products including gentle non-comedogenic cleanser, moisturizer with Sun Protection Factor 30, and moisturizing lotion; however, use of the subject or investigator’s preferred skin care products was permitted.

Study assessment considerations pertaining to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Subjects who were wearing a face mask were to continue to do so until seated in an exam room, in accordance with the local guidelines. The following study procedures were permitted, within the protocol-defined visit windows, to ensure safety of enrolled subjects and continuity of the follow-up visit schedule, due to circumstances when a subject was unable to return to the clinic due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These circumstances included, but were not limited to: shelter-in-place guidelines, quarantines, travel restrictions, clinical site closures, etc. As with all study procedures, clear and complete documentation in source records was required in these circumstances.

- Remote Visits (phone, etc.) in lieu of scheduled office visits for safety and wellness assessment

- Questionnaire completion via email or mail

- Collection and dispensation of study drug (adult family member) as per the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) COVID-19 guidance

The following procedures required an in-office examination to be performed:

- Acne assessments (Invesitigator’s Global Assessment [IGA], lesion counts)

- Local tolerability assessments

- Photographs (for those enrolled at designated imaging centers)

Study discontinuation. Although the importance of completing the entire clinical study was explained to the subjects, any subject was free to discontinue his or her participation in the study at any time and for whatever reason, specified or unspecified, and without prejudice. No constraints were imposed on the subject, and when appropriate, a subject would have been treated with other conventional therapy when clinically indicated. Investigators or the sponsor could also withdraw subjects from the clinical study if deemed necessary.

Dose modifications—Topical study drug. If a subject experienced persistent skin dryness or irritation, the investigator could consider a reduced application frequency for the topical study drug in the first four weeks of the study, for a maximum duration of two weeks. Subjects were instructed to capture all missed topical applications in the dosing calendar. Sites recorded the timing and details of a prescribed dose reduction for topical medication in source records.

Dose modifications—Oral study drug. Dose modification for the oral study drug was allowed for safety reasons only and was to be based on individual investigator clinical judgment. Investigators were to follow the warnings and precautions for doxycycline, which included the discontinuation of oral study drug use if certain medical conditions developed. The decision to discontinue oral study medication due to photosensitivity/exaggerated sunburn reaction required investigator clinical judgment, considering the severity of the condition and location of the erythema (generalized or restricted to areas where topical study drug is applied).

Study participants. Eligble patients were aged 12 years or older with severe facial acne defined as an IGA score of 4 on the face (≥20 inflammatory lesions, 30 to 120 non-inflammatory lesions, and ≤4 nodules). Ineligible patients had cystic acne, beard or facial hair or other dermal conditions that could interfere with assessments, body weight less than 45kg at screening, uncontrolled or serious disease, significantly abnormal laboratory values, known or suspected allergies or sensitivities to study drugs, lactation or plan to conceive during the study. In addition, prohibited medication use and washout periods were specified for acne treatments as well as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, antibiotics, and immunomodulators.

Assessments. Efficacy. Lesion counts were performed and IGA assessed at the screening and all study visits. The primary endpoint was the absolute change in total facial lesion counts from baseline to Week 12; secondary endpoints included changes in inflammatory lesion and non-inflammatory lesion counts and IGA success (IGA 0/1 score plus at least 2-grade improvement).

Subject reported outcomes. Patients completed the Acne-Specific Quality of Life (acne-QoL) questionnaire and a subject satisfaction/drug acceptability questionnaire.

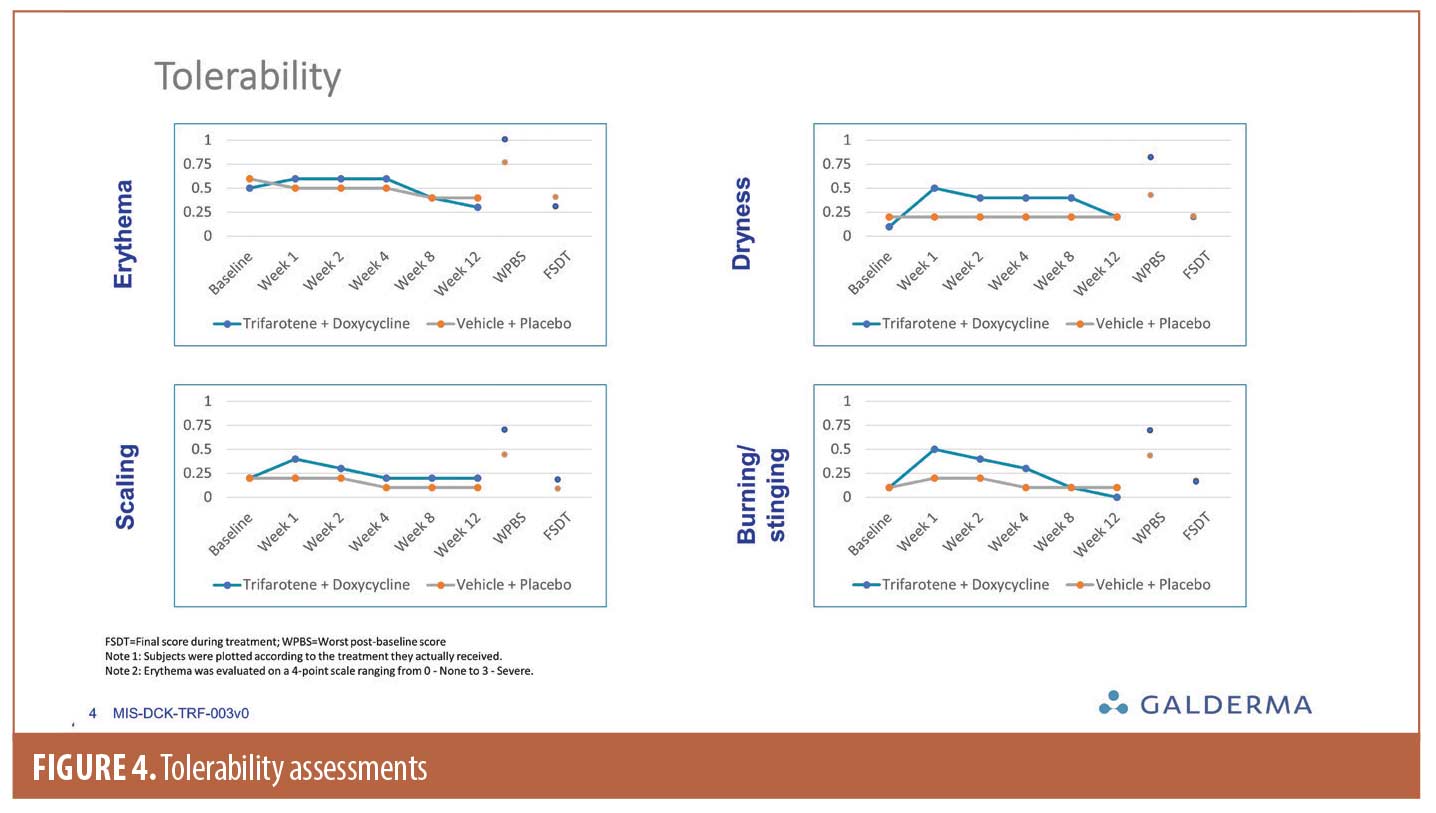

Safety. Safety assessments included treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs), physical exam, and monitoring of vital signs. Local tolerability was assessed for signs and symptoms expected with a topical retinoid (erythema, scaling, dryness, and stinging/burning scored from none=0 to 3=severe). Subjects were also asked about local signs or symptoms at every study visit. Local cutaneous irritation was considered to be an adverse event when severe enough to cause permanent discontinuation of study treatment or required use of additional treatments, including over-the-counter products.

Statistical analysis. Efficacy, safety, laboratory values, and vital signs were summarized by analysis visit. Categorical data were captured by frequency and percentage for each category while continuous data were analyzed by means, medians, range, and standard deviations. Changes in lesion counts were assessed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using baseline counts, analysis center, and treatment as factors. Success rates at Week 12 were analyzed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. Local tolerability scores were summarized by frequency for worst post-baseline score, final score during treatment, and scores for each visit. Adverse events were captured using frequency tables.

Results

Patient population. The study enrolled 202 subjects; 133 randomized to receive T+D and 69 randomized to V+P were included in the intent-to-treat (ITT) and safety populations. Table 1 summarizes subject disposition and study populations. Baseline demographics and acne disease characteristics were comparable between groups as presented in Table 2.

Efficacy. Lesion counts. There was a greater mean absolute change in total lesion counts from baseline to Week 12 (T+D -69.1 vs. -48.1 V+P), with a significant treatment difference (LSMean -21.0, P<0.0001) in favor of T+D. Statistical separation between groups, in favor of T+D, occurred by Week 4 (P<0.05). By Week 12, the percent change in total lesion count was -67.0 percent in the T+D group compared to -45.5 percent in the V+P group. As shown in Figure 1, reductions in individual lesion types were also superior in the T+D group compared to V+P, with a between treatment LSMean difference of -10.0, P<0.0001 for inflammatory lesions and LSMean difference of -11.3, p<0.0001 for non-inflammatory lesions. Figure 2 presents clinical photos of patients treated in the study.

IGA success rates. The proportion of subjects achieving IGA success at Week 12 was 31.7 percent in the T+D group vs 15.8 percent in the V+P group, difference 15.9 percent (P=<0.05). Further, by Week 12, 78.3 percent of subjects in the T+D group had a ≥2-grade improvement compared with 50.1 percent in the V+P group (Figure 3, P=0.0001). Onset of action of T+D was rapidly apparent, as by Week 4 there was a significant separation in proportion of subjects with a ≥2-grade improvement between the T+D group and V+P group.

Subject reported outcomes. The acne QoL questionnaire showed greater reduction in mean score from baseline to Week 12 in the T+D group (-30.8) compared to V+P group (-22.6). On the subject satisfaction questionnaire, 86.2 percent in the T+D group reported being “satisfied” or “very satisfied” compared to 53.8 percent in the V+P group. In addition, 72.3 percent of subjects reported feeling “a lot” or “very much” better after starting treatment with T+D compared to 43.1 percent in the V+P group. The drug acceptability questionnaire showed no relevant differences in use of active or vehicle cream and that patients were satisfied with ease of use.

Safety. TEAEs occurred in 18 (13.5%) subjects in the T+D group and 11 (15.9%) of subjects in the V+P group; two subjects in each group had TEAEs due to COVID-19. No TEAEs were reported to be related to the topical study drug only, while three subjects in each group reported TEAEs related to the oral study drug only. The majority of TEAEs were mild in severity and resolved over time. One subject in the T+D group and two subjects in the V+P discontinued the topical and oral study drug and, eventually, discontinued the study. One subject in the T+D group had a serious TEAE that was unrelated to the study drug (a mental health adverse event). In the T+D group, the most common TEAEs (1.5% subjects each) were diarrhea, nausea, COVID-19, sunburn, headache, and contact dermatitis. In the V+P group, the most common TEAE was COVID-19 (2.9%).

Local tolerability was good in both groups, with a peak (mean score <0.75 for all tolerability scores) occurring at Week 1 followed by improvement over the course of the study (Figure 4).

Discussion

The combination of trifarotene plus oral doxycycline was a safe and effective treatment regimen in subjects with severe acne, and was significantly superior to vehicle and placebo in improving severe acne; there were highly significant and clinically relevant improvements in both IGA and lesion counts after 12 weeks of active treatment compared to V+P. Although each arm had two components, the study design was intended to compare an active versus placebo arm; an arm consisting of monotherapy of either oral doxycycline or trifarotene was not considered suitable because it would not follow current acne treatment guidelines for severe disease.17 There was a relatively high placebo response, which may be at least partially attributable to the natural waxing and waning course of acne. Patients were instructed about applying medication and the use of cleanser and moisturizer at each visit; this also may have contributed to a robust placebo response.

There are relatively few published studies reporting the efficacy of topical treatment regimens in severe acne (e.g., IGA 4, mean total lesion counts >100); thus, there is need for evidence-based information concerning treatment options in this patient population. Furthermore, lesion counts alone may not be sufficient as the metric to determine whether two acne studies enrolled populations with similar severity. Stein-Gold et al20 have reported that both acne lesion types and lesion quantities should be considered in an overall assessment of acne severity. Despite the limited comparability of existing studies in severe acne, published data from Dreno et al9 and Gold et al10 support the conclusions of this study that the combination of a retinoid with oral doxycycline is an appropriate regimen for severe acne.

Isotretinoin is an effective oral treatment for severe acne, but it has side effects that some patients consider intolerable and that can sometimes persist after treatment cessation.21 An acne flare may occur at the beginning of oral retinoid treatment, providing a rationale for using a topical retinoid before initiating therapy. In addition, isotretinoin monitoring can be onerous for both clinicians and patients.22,23 The potential for teratogenicity has led to creation of stringent pregnancy prevention programs in many countries, such as the somewhat controversial risk evaluation and mitigation program named iPLEDGE in the United States.23 These programs combined with monitoring requirements pose a major administrative burden to clinicians and patients, and many in the field of dermatology have called for reform.23, 24 In a survey of general practitioners in Ireland (n=298), 17 percent indicated that they would prescribe isotretinoin therapy, citing long wait times for dermatology consultation. The remaining 83 percent of respondents who did not prescribe isotretinoin gave the following as barriers to use: medical-legal concerns (61%), lack of awareness that they could prescribe isotretinoin (55%), and lack of familiarity in managing patients on isotretinoin (41%).25 Additionally, Landis22 reported that prescribing and monitoring protocols have wide variations among clinicians, suggesting that much could be done to optimize use of isotretinoin. However, until change occurs, it is vital for clinicians to have alternatives to isotretinoin therapy for patients with severe acne.

Limitations. Limitations of the study include lack of an active comparator.

Conclusion

Combination therapy with a topical retinoid and oral antibiotic is an efficacious therapy for severe acne, with a rapid onset of action and good safety and tolerability.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank our DUAL co-investigators: John Browning, MD; Francisco Flores, MD; Fred Ghali, MD; Kimberly Grande, MD; Steve Grekin, MD; Charles Hudson, MD; Cheryl Hull, MD; Steven Kempers, MD; Megan Landis, MD; Mark Ling, MD; Stephen Miller, MD; Angela Moore, MD; Mark Nestor, MD; Elyse Rafal, MD; Ann Reed, MD; Stephen Schleicher, MD; and Dow Stough, MD. We acknowledge the writing support of Valerie Sanders of Sanders Medical Writing.

References

- Thiboutot D, Dreno B, Abanmi A, et al. Practical management of acne for clinicians. An international consensus from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018; 78 (2 Suppl 1):S1–S23.

- Tan AU, Schlosser BJ, Paller AS. A review of diagnosis and treatment of acne in adult female patients. Int J Women’s Dermatol. 2018;4(2):56–71.

- Tan J, Beissert S, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Impact of facial and truncal acne on quality of life: A multi-country population-based survey. J Am Acad Dermatol Int. 2021;3:102–110.

- Brodell RT, Schlosser BJ, Rafal E, et al. A fixed-dose combination of adapalene 0.1%-BPO 2.5% allows an early and sustained improvement in quality of life and patient treatment satisfaction in severe acne. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23(1):26–34.

- Brown BC, McKenna SP, Siddhi K, et al. The hidden cost of skin scars: quality of life after skin scarring. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(9):1049–1058.

- Chuah SY, Goh CL. The impact of post-acne scars on the quality of life among young adults in Singapore. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8(3):153–158.

- Gieler U, Gieler T, Kupfer JP. Acne and quality of life – impact and management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29 Suppl 4:12–14.

- Hayashi N, Miyachi Y, Kawashima M. Prevalence of scars and “mini-scars”, and their impact on quality of life in Japanese patients with acne. J Dermatol. 2015;42(7):690–696.

- Dreno B, Kaufmann R, Talarico S, et al. Combination therapy with adapalene-benzoyl peroxide and oral lymecycline in the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(2):383–390.

- Gold LS, Cruz A, Eichenfield L, et al. Effective and safe combination therapy for severe acne vulgaris: a randomized, vehicle-controlled, double-blind study of adapalene 0.1%-benzoyl peroxide 2.5% fixed-dose combination gel with doxycycline hyclate 100 mg. Cutis. 2010;85(2):94–104.

- Kircik LH. Anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline plus adapalene 0.3% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel for severe acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(9):924–927.

- Zaenglein AL, Shamban A, Webster G, et al. A phase IV, open-label study evaluating the use of triple-combination therapy with minocycline HCl extended-release tablets, a topical antibiotic/retinoid preparation and benzoyl peroxide in patients with moderate to severe acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(6):619–625.

- Rollman O, Vahlquist A. Oral isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) therapy in severe acne: drug and vitamin A concentrations in serum and skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;86(4): 384–389.

- Tan J, Stein Gold L, Schlessinger J, et al. Short-term combination therapy and long-term relapse prevention in the treatment of severe acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(2):174–180.

- Tan J, Thiboutot D, Popp G, et al. Randomized phase 3 evaluation of trifarotene 50 mug/g cream treatment of moderate facial and truncal acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6): 1691–1699.

- Blume-Peytavi U, Fowler J, Kemeny L, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of trifarotene 50 mug/g cream, a first-in-class RAR-gamma selective topical retinoid, in patients with moderate facial and truncal acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(1):166–173.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5): 945–73 e33.

- Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5 Suppl):S1–50.

- Dreno B, Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in dermatology: limiting antibiotic use in acne. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24(3):330–334.

- Stein Gold L, Tan J, Kircik L. Evolution of acne assessments and impact on acne medications: An evolving, imperfect paradigm. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(1):79–86.

- Hull PR, Demkiw-Bartel C. Isotretinoin use in acne: Prospective evaluation of adverse events. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4(2):66–70.

- Landis MN. Optimizing isotretinoin treatment of acne: Update on current recommendations for monitoring, dosing, safety, adverse effects, compliance, and outcomes. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(3):411–419.

- Barbieri JS, Frieden IJ, Nagler AR. Isotretinoin, patient safety, and patient-centered care-time to reform iPLEDGE. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(1):21–22.

- Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, et al. Oral isotretinoin and pregnancy prevention programmes. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(2):466-467; author reply 7-8.

- Carmody K, Rouse M, Nolan D, et al. GPs’ practice and attitudes to initiating isotretinoin for acne vulgaris in Ireland: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(698):e651–e6.