J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(11):40–44

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(11):40–44

by Taraneh Yazdanparast, MD; Saman Ahmad Nasrollahi, PharmD, PhD; Leila Izadi Firouzabadi, MD; and Alireza Firooz, MD

Drs. Yazdanparast, Nasrollahi, and Firouzabadi are with the Center for Research and Training in Skin Diseases and Leprosy at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran. Dr. Yazdanparast is also with the Telemedicine Research Center at the National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran. Dr. Firooz is with the Clinical Trial Center at Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran.

FUNDING: This study was supported by a research grant from Manousha Darou Co. in Tehran, Iran.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Background.Contact dermatitis is a common skin condition observed by dermatologists, presenting a burden on healthcare systems. Recently, there has been a trend in producing skin-identical topical preparations for the repair of skin. However, there is a limited number of experimental studies to assess the safety and efficacy of this products.

Objective. This study assessed the clinical efficacy and safety of a skin-identical ceramide complex cream (Dermalex Repair Contact Eczema; Omega Pharma, Nazareth, Belgium) in the treatment of contact dermatitis.

Design.This was a Phase II, before-after trial.

Setting. This study was conducted at the Center for Research and Training in Skin Diseases and Leprosy (CRTSDL) at Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran. Participants.Fifteen patients with contact dermatitis (8 men and 7 women) between the ages of 25 and 62 years (median age: 36.4 years) were enrolled in this study.

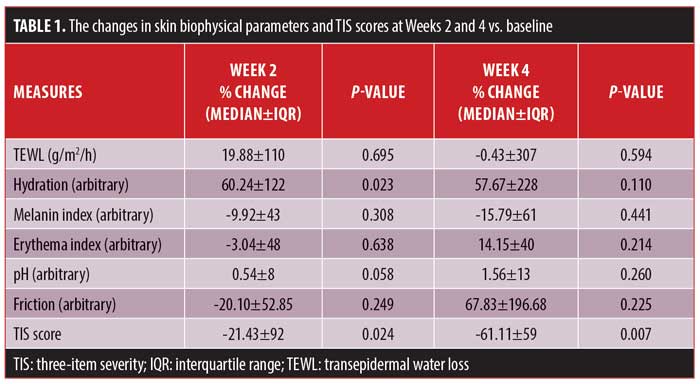

Measurements. Changes were assessed using six skin biophysical parameters (transepidermal water loss [TEWL], stratum corneum [SC] hydration, melanin index, erythema index, skin pH, and skin friction), Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score, and Three-Item Severity (TIS) score at baseline, Week 2, and Week 4 of the study.

Results.Skin hydration and TIS showed a statistically significant improvement after treatment with study cream (p=0.023 and p=0.007, respectively). Although the reduction in TEWL was not significant, a slight decrease was observed at Week 4.

Conclusions. The skin-identical ceramide complex cream improved contact dermatitis with a decrease in TIS and an increase in skin hydration, implying a repair of the skin barrier.

Keywords: Contact dermatitis, skin-identical ceramide complex, topical repair cream

Introduction

Contact dermatitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the skin that occurs as a result of contact with chemical substances. The acute form presents with pruritus, erythema, and vesiculation, whereas chronic contact dermatitis is characterized by pruritus, xerosis, lichenification, hyperkeratosis, and fissure. Contact dermatitis can involve any part of skin—in particular, the face and upper and lower extremities.1,2 The majority of cases (about 80%) are irritant-contact dermatitis, while 20 percent are caused by allergens.3,4 Multiple extrinsic and intrinsic factors affect the development of contact dermatitis. Notable extrinsic factors include occupation, geographic, environmental, and cultural factors.2 Intrinsic factors include age, sex, race, epidermal barrier integrity, atopic diathesis, and genetics.5 The most common irritants to cause contact dermatitis include household cleaning products, acids and bases, industrial solvents and other chemicals, certain plants, clothing materials, and airborne irritants (e.g., air pollution, pollen, mold).6

Contact dermatitis prevalence in the United States is estmated to be about 136 cases per 10,000 individuals.8 According to the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, there were 588 million estimated dermatology visits between the years 1993 and 2010, with contact dermatitis being among the most common diagnoses;9 this suggests that contact dermatitis presents a notable burden on healthcare systems.6 Contact dermatitis has also been significantly linked with a decrease in the quality of life.7

In addition to proper education of patients regarding the prevention and avoidance of irritant and allergen exposures, effective treatments for contact dermatitis are needed. The basis of treatment currently involves humectants and topical steroids.10–12 There is evidence of the beneficial effects of repair creams in the treatment and prevention of contact dermatitis.13,14 There is also a trend in producing topical repair cream preparations with components identical to the skin; however, there is a limited number of experimental studies demonstrating the efficacy of these products in the treatment of contact dermatitis.15

In the present study, we aimed to determine the efficacy and safety of a topical repair cream containing the skin-identical ceramide complex (Dermalex Repair Contact Eczema cream, [Omega Pharma, Nazareth, Belgium]) claimed to be useful as a method of barrier recovery in the treatment of contact dermatitis.

Methods

This study was a Phase II, before-after trial involving patients with contact dermatitis who were referred to the Center for Research and Training in Skin Diseases and Leprosy (CRTSDL) at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the CRTSDL and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and principles of Good Clinical Practice. The method of study was explained to all volunteers, and written informed consent was obtained.

Inclusion criteria included being18 to 65 years of age and having mild-to-moderate irritant- or allergen-related contact dermatitis, as diagnosed by a dermatologist based on clinical and/or histological findings), and having otherwise a normal health status. Exclusion criteria included sensitivity to the study cream or any of its constituents, use of any other topical moisturizing formulation during the study, exposure to any chemical solvent or solution during the study, used of any oral or topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors for at least four weeks prior to the study, and/or undergoing chemotherapy within one year prior to or during the study period.

The study cream contains the following ingredients: skin identical ceramide complex, modified alumino-silicates, purified water, glycerol, glyceryl stearate, cocoglycerides, cetyl alcohol, isopropyl myristate, ceteareth-20, ceteareth-12, cetearyl alcohol, cetyl palmitate, dehydroacetic acid, benzyl alcohol, and alkaline earth minerals.

After participant selection, the area of contact dermatitis for each patient was marked and photographed and biophysical characteristics of the lesions, including transepidermal water loss (TEWL), stratum corneum (SC) hydration, melanin index, erythema index, skin pH, skin friction, and skin surface sebum, were measured by the tewameter, corneometer, mexameter, pH-meter, frictiometer, and sebumeter probes of the Cutometer®MPA 580 (CK Company, Cologne, Germany)16–22 in standard environmental conditions of 21°±2°C and 40±5 percent humidity.

Patients were requested to apply one fingertip unit (FTU) of the study cream on their lesions at least three times a day, or after bathing or washing the body part, for four weeks. All measurements were repeated on the same area as baseline at Weeks 2 and 4 of the study, and the changes were calculated using to the following formula:

Percentage change after treatment=[(value after treatment ? value at baseline) / value at baseline] × 100

The change in the skin surface sebum content of the lesion was calculated differently, as the rate of sebum was zero at baseline in some patients, so division was not possible:

Change after treatment=value after treatment ? value at baseline

A Three-Item Severity score (TIS score)23 was also calculated and assessed at baseline, Week 2, and Week 4 following treatment by a dermatologist. TIS score (0–9 points) was calculated as the sum of the three items of erythema (i.e., redness, 0–3 points), edema (0–3 points), and excoriation (scratches) (0–3 points).

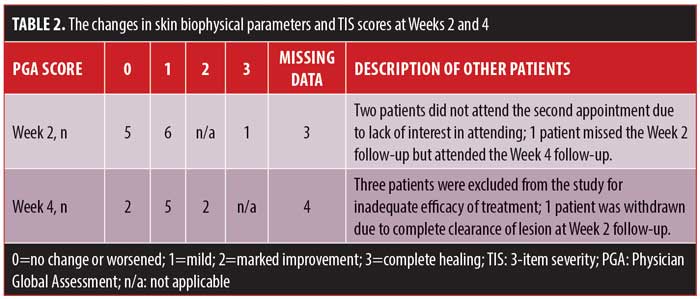

A digital photograph was taken of each patient’s lesion at each visit to assess Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score.24 PGA score is a standardized, feasible, and straightforward outcome measure that was scored as follows: 0=no change or worsening, 1=mild improvement (less than 50%), 2=marked improvement (50%–99%), and 3=Complete healing (100%).

Participant satisfaction was measured by use of a Visual Analog Scale (VAS)25 at Weeks 2 and 4 of treatment. Side effects, including pruritus, burning sensation, dryness, erythema, and scaling, were also evaluated and recorded on a four-point scale, with 0=none, 1=mild, 2=moderate, and 3=severe. In the case of any severe side effects, patients were instructed to stop the application of the study cream and an assessment of the skin was performed on the same or next day.

All of the statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York) and analyzed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and nonparametric test for normal distribution parameters. A P value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

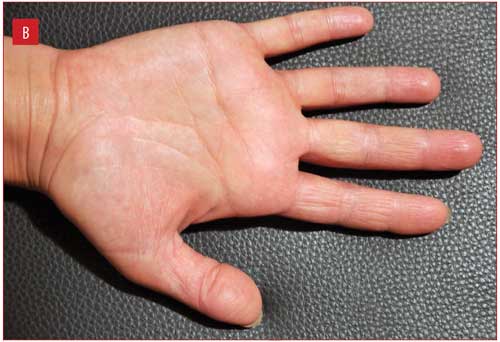

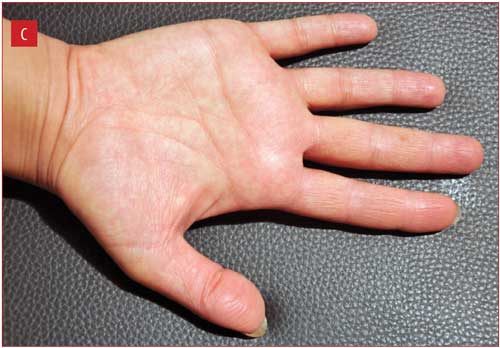

Fifteen patients with contact dermatitis (8 men, 7 women) ranging in age from 25 to 62 years (median age: 36.4 years) were enrolled in the study. The most common anatomic site of involvement was the dorsal hand (6 patients), followed by the palmar hand (5 patients), volar forearm (2 patients), volar wrist (1 patient), and anterior part of the leg (1 patient). Two patients were lost to follow up at Week 2 due to lack of interest in attending follow-up appointments; three patients withdrew at Week 2 due to inadequate efficacy of study cream, and were subsequently treated with topical steroids; and one patient withdrew due to complete clearance of the lesion at Week 2. Ultimately, nine patients completed the trial according to the study protocol.

The changes in six skin biophysical parameters (i.e., TEWL, hydration of the SC, melanin index, erythema index, pH, and friction), as well as the TIS scores at Weeks 2 and 4 of treatment were compared with baseline measurements and are shown in Table 1. TIS scores decreased significantly at both Week 2 and Week 4 of treatment (Figure 1), while SC hydration increased significantly at Week 2 and nonsignificantly at Week 4.

The median of sebum change was 2.50 (interquartile range [IQR)=4.50] at Week 2 and 0 (IQR=0) at Week 4 of treatment (p=0.395 and p=0.593, respectively).

The median patient satisfaction scores (VAS score) were 5 (IQR=1.88) and 5.5 (IQR=3.5) at Week 2 and Week 4 of treatment, respectively. The PGA scores of patients are summarized in Table 2.

Regarding side effects, two patients reported pruritus following application of the study cream, which improved following treatment with an oral cetirizine tablet. One patient also reported burning at the time of application.

Figure 1 illustrates improvement in one patient from baseline to Week 2, with complete clearance at Week 4.

Discussion

The SC is a mixture of corneocytes and keratinocytes that have passed the process of terminal differentiation. SC mostly consists of ceramides (50%), cholesterol (25%), and free fatty acids (15%). Keratinocytes contain lamellar bodies; however, lamellar bodies appear when keratinocytes differentiate, and the upper stratum spinosum layer is the first layer in which they are present.26

Ceramides reduce TEWL through the cohesion of corneocytes and maintain the permeability barrier function of the skin. A decrease in ceramide content has been associated with a reduction in barrier function in many skin disorders.27 Topical preparations, such as moisturizers, cosmetics, and dermatologic medications, that contain lipids similar to those found in the skin, especially ceramides, might be useful in the treatment of certain skin diseases by way of improving the skin’s barrier functioning.27,28

The cream used in this study contains mostly ceramide (CER-6), phytosphingosine, and cholesterol, and demonstrated improvement in contact dermatitis and SC hydration. TIS score, an indicator of objective signs of dermatitis, demonstrated significant improvement at Weeks 2 and 4 (a 21% and a 61% decrease, respectively) following treatment with the study cream, which denotes a significant decrease in dryness, scaling, erythema, and edema.

The other ingredients of the study cream include alkaline minerals such as magnesium chloride and calcium chloride. Some inorganic salts have improved skin irritation by increasing skin hydration and skin barrier function.29 A recent clinical trial demonstrated that topical application of a cream containing magnesium chloride was effective in the treatment of diaper dermatitis among 64 children under the age of two years with diaper dermatitis.30 In another study by Proksch et al,31 30 subjects with known atopic dermatitis submerged their forearm for 15 minutes daily for six weeks in a magnesium-rich dead sea salt solution. The authors report significantly improvements in the skin barrier function and SC hydration while reducing skin inflammation and roughness. Although several studies have shown that the application of calcium chloride solely decreased the recovery of skin barrier,32,33 a review article by Denda34 reported that a mixture of calcium chloride and magnesium chloride was shown to accelerate barrier recovery.34 The cream we used in our study also comprises alumino silicates (bentoquatam), which have been shown to shield and protect the skin.35

Reduction in skin surface sebum has been reported in atopic dermatitis and might be responsible for skin dryness and impaired function of the epidermal barrier.36 In our study, sebum increased among participants after two weeks of treatment with study cream, and then returned to baseline levels after four weeks. Thus, its use did not cause a significant change in skin surface sebum. This lack of change could be due to the different uncontrollable factors that affect the amount of sebum in the individual patients , such as psychological stress, nutritional status, menstrual cycle, and circadian rhythm.37,38,39,40

Kucharecova et al15 showed that a lipid-rich emollient containing ceramide significantly suppressed proliferating cells in a manner that was correlated with the suppression of erythema score, but our results did not reveal any significant changes in the erythema index.

Normal skin pH is acidic, ranging in values of 4 to 6 depending on endogenous and exogenous elements.41 All of our patients, except for one, had pH values higher than 5.5 at the beginning of the study. Not surprisingly, the pH remained almost the same after treatment. The nature of mineral salt in the study cream, which is alkaline, might be responsible for this observation. Even rinsing the skin with water alone immediately led to a temporary increase in the skin pH, and conventional soap produced a rise in pH that took 90 minutes to be completely normalized.42 The application of syndet bars rather than conventional cleansers yields an acidic environment42 and might recommended for use in patients with dermatitis.

The TEWL, an indicator of skin barrier function, did not show any statistically significant changes during treatment with the study cream. Research has shown that acidification of the epidermis decreases TEWL,43 and the stability of TEWL in our study could be due to a lack of change in skin pH. Nevertheless, there was a nonsignificant decrease of TEWL after four weeks of treatment in our patients, which suggests an improvement in the barrier permeability. This reduction could be a result of cornified layer repair during this short period of time, and there is a possibility of achieving a significant effect by extending the duration of the treatment.

Because the study cream contains alkaline earth minerals, it acts as a moisturizer and regulates electrolyte levels in the epidermis. Oue results suggest that the study cream is capable of improving mild-to-moderate contact dermatitis and might be an effective alternative to steroid therapy for the types of contact dermatitis included in the study. It might also be beneficial in severe cases of dermatitis as an adjunctive therapy to decrease the dose and/or the frequency of steroid application, which might reduce steroid complications.

A study of 580 individuals with atopic or irritant/allergic contact dermatitis evaluated the efficacy of a topical skin lipid mixture containing ceramide-3 and patented nanoparticles. 44 The authors reported that balanced lipid mixtures were effective in improving barrier function and the clinical condition of the skin.There are several classes of ceramides in the skin, with the main ceramide in the lamellar organelles being ceramide-1.45,46 The cream in the current study contains ceramide-6, and replacing this ceramide with ceramide-1 might increase the efficacy of the cream.15

Conclusion

Our results indicate that an emollient-containing, skin-identical ceramide complex medication is useful as a mono- or adjunctive therapy for mild-to-moderate contact dermatitis, potentially due to its positive effects on the skin barrier function. Randomized, controlled studies with larger patient cohorts are needed to support our findings.

References

- Bourke J, Coulson I, English J. Guidelines for the management of contact dermatitis: an update. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(5):946–954.

- Belsito DV. Occupational contact dermatitis: etiology, prevalence, and resultant impairment/disability. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2): 303–313.

- Marks JG Jr., Elsner P, DeLeo VA. Allergy and ICD. In: Contact and Occupational Dermatology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, 2002: 3–15.

- Antezana M, Parker F. Occupational contact dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2003;23(2):269–290.

- Wojciechowska M, Czajkowski R, Kowaliszyn B, et al. Analysis of skin patch test results and metalloproteinase-2 levels in a patient with contact dermatitis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32(3):154–161.

- Cashman MW, Reutemann PA, Ehrlich A. Contact dermatitis in the United States: epidemiology, economic impact, and workplace prevention. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(1):87–98.

- Sanclemente G, Burgos C, Nova J, et al. The impact of skin diseases on quality of life: a multicenter study. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017; 108(3):244–252.

- Hogan DJ, Ledet JJ. Impact of regulation on contact dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27(3):385–394.

- Landis ET, Davis SA, Taheri A, et al. Top dermatologic diagnosis by age. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(4):22368

- Fonacier L, Bernstein DI, Pacheco K, et al. Contact dermatitis: a practice parameter-update 2015. J Allergy Clin Immunol Prac. 2015;3:S1–S39.

- Bangash HK, Petronic-Rosic V. Acral manifestations of contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35(1):

9–18. - Mostosi C, Simonart T. Effectiveness of barrier creams against irritant contact dermatitis. Dermatology. 2016;232(3):353–362.

- Jordan L. Efficacy of a hand regimen in skin barrier protection in individuals with occupational irritant contact dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:

s81–s85. - von Grote EC, Palaniswarmy K, Meckfessel MH. Managing occupational irritant contact dermatitis using a two-step skincare regimen designed to prevent skin damage and support skin recovery. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(12):1504–1510.

- Kucharekova M, Schalkwijk J, Van De Kerkhof PC, et al. Effect of a lipid-rich emollient containing ceramide 3 in experimentally induced skin barrier dysfunction. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46(6): 331–338.

- Shah JH, Zhai H, Maibach HI. Comparative evaporimetry in man. Skin Res Technol. 2005;11(3):205–208.

- Yosipovitch G, Xiong GL, Haus E, Sakett-Lundeen L, et al. Time-dependent variations of the skin barrier function in humans: transepidermal water loss, stratum corneum hydration, skin surface pH, and skin temperature. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110(1):20–23.

- Gerhardt LC, Strässle V, Lenz A, et al. Influence of epidermal hydration on the friction of human skin against textiles. J R Soc Interface. 2008;5(28):1317–1328.

- Yamamoto T, Takiwaki H, Arase S, et al. Derivation and clinical application of special imaging by means of digital cameras and Image J freeware for quantification of erythema and pigmentation. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14:26–34.

- Yosipovitch G, Tur E, Morduchowicz G , et al. Skin surface pH, moisture and pruritus in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8(10):1129–1132.

- Ryu HS, Joo YH, Kim SO, et al. Influence of age and regional differences on skin elasticity as measured by the Cutometer. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14:

354–358. - Pande SY, Misri R. Sebumeter. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:444–446.

- Oranje AP. Practical issue on interpretation of scoring atopic dermatitis: SCORAD Index, objective SCORAD, patient-oriented SCORAD and Three-Item Severity score. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2011;41:149–155.

- Pascoe VL, Enamandram M, Corey KC, et al. Using the Physician Global Assessment in a clinical setting to measure and track patient outcomes. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(4): 375–381.

- Voutilainen A, Pitkäaho T, Kvist T, et al. How to ask about patient satisfaction? The visual analogue scale is less vulnerable to confounding factors and ceiling effect than a symmetric Likert scale. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(4):946–957.

- 26- Feingold KR. Thematic review series: skin lipids. The role of epidermal lipids in cutaneous permeability barrier homeostasis. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(12):2531–2546.

- Coderch L, López O, de la Maza A, et al. Ceramides and skin function. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4(2):107–129.

- Draelos ZD. New treatments for restoring impaired epidermal barrier permeability: skin barrier repair creams. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30(3):345–348.

- Fatemi S, Jafarian-Dehkordi A, Hajihashemi V, et al. A comparison of the effect of certain inorganic salts on suppression acute skin irritation by human biometric assay: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:102.

- Nourbakhsh SM-K, Rouhi-Boroujeni H, Kheiri M, et al. Effect of topical application of the cream containing magnesium 2% on treatment of diaper dermatitis and diaper rash in children: a clinical trial study. J Clin Diag Res. 2016;10(1): WC04-WC06.

- Proksch E, Nissen HP, Bremgartner M, et al. Bathing in a magnesium-rich Dead Sea salt solution improves skin barriers function, enhances skin hydration, and reduces inflammation in the atopic dry skin. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(2): 151–157.

- Lee SH, Elias PM, Proksch E, et al. Calcium and potassium are important regulators of barrier homeostasis in murine epidermis. J Clin Invest. 1992;89(2):530–538.

- Menon GK, Price LF, Bommannan B, et al. Selective obliteration of the epidermal calcium gradient leads to enhanced lamellar body secretion. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102(5):789–795.

- Denda M. New strategies to improve skin barrier homeostasis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54 Suppl 1:S123–SW130.

- Scott MJ, Heumann MA, DeBruyckere DM, et al. The feasibility of using skin protectant products and education to prevent poison oak. Wilderness Environ Med. 2002;13(3):206–208.

- Firooz A, Gorouhi F, Davari P, et al. Comparison of hydration, sebum and pH values in clinically normal skin of patients with atopic dermatitis and healthy controls. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32(3):321–322.

- Alexopoulos A, Chrousos GP. Stress-related skin disorders. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2016;17(3):

295–304. - Tabri F, Patellongi I, Wahab S, Djawad Kh. Analysis of nutritional status and levels of sebum on various age groups. American Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2017;5(1):26–29.

- Raghunath RS, Venables ZC, Millington GW. The menstrual cycle and the skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40(2):111–115.

- Le Fur I, Reinberg A, Lopez S, et al. Analysis of circadian and ultradian rhythms of skin surface properties of face and forearm of healthy women. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(3):718–724.

- Ali SM, Yosipovitch G, Skin pH: from basic science to basic skin care. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(3):261–267.

- Schmid-Wendtner MH, Korting HC. The pH of the skin surface and its impact on the barrier function. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;19(6): 296–302.

- Eberting CL, Coman G, Blickenstaff N. Repairing a compromised skin barrier in dermatitis: leveraging the skin’s ability to heal itself. J Allergy Ther. 2014;5(5):187.

- Berardesca E, Barbareschi M, Veraldi S, Pimpinelli N. Evaluation of efficacy of a skin lipid mixture in patients with irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis or atopic dermatitis: a multicenter study. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45(5):280–285.

- Pappas A. Epidermal surface lipids. Dermato Endocrinol. 2009;1:72–76.

- Zeichner JA, Del Rosso JQ. Multivesicular emulsion ceramide-containing moisturizers: an evaluation of their role in the management of common skin disorders. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9(12): 26–32.