J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(9):20–24.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(9):20–24.

by Sheetal Sapra, MD, FRCPC; Shantel DJ Lultschik, BHSc; Jennifer VH Tran, BSc; and Kevin Dong

All authors are with the Institute of Cosmetic and Laser Surgery in Oakville, Ontario.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Objective. To evaluate concomitant therapy of oral isotretinoin with multiplex pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser.

Methods. A retrospective chart review of patients who received treatment of oral isotretinoin and non-ablative laser therapy to treat acne vulgaris at a single outpatient dermatology clinic site in Ontario, Canada between 2009 and 2017.

Results. 187 patients were included, consisting of 45.5 percent males (n=85) and 54.5 percent females (n=102) with a mean age of 21.4 years. 31.6 percent (n=59) of patients reported experiencing side effects from concomitant isotretinoin and NAL therapy, the most common being eczema (n=14), erythema (n=11), significant dry skin/lips/eyes (n=8), flushing (n=6), and bruising (n=6). 99.2 percent of patients achieved clear or almost clear at treatment completion. Of those who expressed satisfaction, 65.2 percent (n=122) reported being satisfied with the treatment and the remaining patients did not report satisfaction nor dissatisfaction.

Limitations. Limitations exist mainly due to the absence of standardized lesion counts and a comparator cohort. Thus, it is not possible to comment on whether the combination of isotretinoin and NAL is more efficacious that either treatment alone.

Conclusion. Concomitant use of isotretinoin and non-ablative laser therapy is a safe and effective treatment option for acne vulgaris that provides patient satisfaction.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris, isotretinoin, non-ablative laser, pulsed dye laser, nd:yag

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the pilosebaceous follicles.1 Acne is associated with significant physical and psychological morbidity, such as anxiety, depression, poor self-esteem, and permanent scarring.1, 2 Due to acne’s adverse effect on quality of life, it is important to offer effective and safe treatment options to patients.2 Treatments for acne include topical and systemic medication, as well as therapies such as ablative and non-ablative laser treatments or chemical peels.1 This study will focus on the combination of oral isotretinoin and non-ablative laser (NAL), specifically multiplex pulsed dye laser (PDL) and Nd:YAG laser delivered through one unique device.

Oral isotretinoin is considered the most efficacious treatment with the ability to affect all pathogenic factors of acne.1,3,4 Canadian, American, and European clinical practice guidelines suggest isotretinoin be used for moderate to severe acne, and only as a first-line treatment to treat severe nodulocystic and papulopustular acne.5-8 In a recent review study, complete improvement was observed in 93.9 percent of patients, with only mild side effects, such as cheilitis (90-100% of patients).9 NAL therapies have been shown to effectively and safely treat both active acne and acne scarring. Nd:YAG laser and PDL treat active acne by causing thermal coagulation of the sebaceous glands, leading to decreased sebum production.10

Combination therapies are often successful in treating acne; however, as per the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines, there is hesitancy to combine oral isotretinoin with NAL therapies.1 Meanwhile, there are no Canadian-specific guidelines regarding oral isotretinoin and NAL therapy usage. Early case studies saw poor wound healing and keloid formation in patients who had concurrently or recently taken isotretinoin and received NAL or ablative laser therapy, leading to the AAD recommendation to delay cutaneous laser treatments until 6 to 12 months after discontinuing isotretinoin.1,11-13 In contrast, recent research has supported the safety of NAL treatment during isotretinoin use, where studies report no evidence of scarring, keloid formation, or abnormal wound healing and there was insufficient evidence to support delaying treatments such as NAL procedures.14-17 A slight majority of physicians surveyed would recommend patients wait at least six months or longer after isotretinoin use before undergoing NAL treatment; however, 76 percent of experts have never seen complications with NAL treatment while receiving isotretinoin or within six months.11,16

Currently, literature is not conclusive on the use of non-ablative laser therapies during and following the use of oral isotretinoin, leading to physician hesitancy to pursue this treatment modality. The primary objective of this study is to assess the safety of oral isotretinoin in combination with multiplex PDL and Nd:YAG laser in order to strengthen recommendations for its use as a treatment option for acne vulgaris. Secondary objectives include the assessment of effectiveness and patient satisfaction.

Methods

Data collection. A retrospective medical chart review of patients who received treatment of oral isotretinoin with multiplex PDL and Nd:YAG laser therapy to treat acne vulgaris was conducted. All patients received treatment at one outpatient dermatology clinic site. A research ethics board approved this study prior to all chart review activities. A waiver for consent was obtained due to the retrospective nature of the study, although patients included in the photo figures provided written consent to the use of these photos for research purposes. The electronic database was searched to find all patients who received both oral isotretinoin and NAL therapy from January 1st, 2009 to August 17th, 2017 for treatment of acne vulgaris. NAL therapy consisted of sequential emission of 585nm PDL and 1064nm Nd:YAG from one unique, multiplex delivery system (Cynergy™, Cynosure®; Westford, Massachusetts, United States). The following settings were used for the laser therapy: fluence 6-8J/cm2, spot size 10mm, and pulse duration 10-20ms depending on skin type. Patients were not incentivized to receive concomitant treatment and paid for multiplex PDL and Nd:YAG laser with isotretinoin therapy. Exclusion criteria included patients who did not return to the study site for follow-up after the initial prescription was provided, patients who received multiplex PDL and Nd:YAG laser therapy only prior to taking oral isotretinoin or started more than six months after taking oral isotretinoin, and patients who received oral isotretinoin with multiplex PDL and Nd:YAG laser therapy for any indication other than acne vulgaris. Demographic data of study participants is included in Table 1.

Clinical evaluations for effectiveness, patient reported satisfaction, and safety and tolerability of oral isotretinoin with multiplex PDL and Nd:YAG laser therapy were completed from review of chart notes. Side effects experienced by study participants is included in Table 2. Investigator Global Assessments (IGA) and photographic demonstrations of the face were taken before and after treatment completion. Effectiveness of concomitant treatment experienced by study participants is included in Table 3.

Statistical analysis. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 20.0.0 Software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). The outcomes of the categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages for the group of patients. The numerical values, which consisted of follow up, age, and number of NAL treatments were summarized by means, standard deviations as well as minimum and maximum values.

Results

A total of 187 patients were identified to have received NAL treatment either during or after isotretinoin use to treat facial acne after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The patient population consisted of 45.5 percent males (n=85) and 54.5 percent females (n=102). The mean age at initiation of treatment was 21.4 with a minimum age of 12 and a maximum of 47. All patients had clinical Investigator Global Assessment acne grading of moderate or severe facial acne (100%, n=187) with 56.1 percent (n=105) also having acne scarring and 10.7 percent (n=20) also having cystic acne.

98.4 percent of patients were given an initial dosage of isotretinoin of 40mg per day (n=184), 1.1 percent of patients initially received 10mg per day (n=2), and 0.5 percent of patients initially received 80mg per day (n=1). It is to be noted that four patients had their prescription altered during treatment at the discretion of the clinician. Two patients decreased their dosage from 40mg to 20mg, one patient decreased their dosage from 40mg to 20mg to 10mg, and one patient increased their dosage from 40mg to 80mg.

100 percent of patients were treated with multiplex 585nm PDL and 1064nm Nd:YAG delivered by one unique device (n=187). 6.4 percent of patients received NAL therapy starting within six months after their prescription of isotretinoin ended (n=12), while 53.5 percent of patients received NAL therapy only during the usage of isotretinoin (n=100) and 40.1 percent of patients received NAL therapy both during and after isotretinoin usage (n=75). On average, a patient received 3.8 NAL treatments while taking isotretinoin with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 18, 1.5 NAL treatments after isotretinoin treatment with a minimum of zero and a maximum of 13, and a combined total of 5.3 NAL treatments with a minimum of one and a maximum of 25. Standard deviation values were 2.4, 2.5 and 3.6 respectively. The mean follow up time was 902.7 days (SD=870.9 days), with a minimum of 63, and a maximum of 3520 days.

Overall, 31.6 percent of patients experienced side effects while on concomitant isotretinoin and NAL therapy (n=59). None of the side effects were classified as serious. The most common side effects include eczema (6.6%, n=14), significant dry skin/lips/eyes (3.8%, n=8), erythema (5.2%, n=11), flushing (2.8%, n=6), and bruising (2.8%, n=6). There were four report of pain (1.9%) and three reports each of nosebleeds and mild depression (1.4%). There were two reports each of hyperpigmentation, cheilitis, sore throat, unspecified mood change, joint pain, fatigue, cold sores, and elevated liver enzyme levels (0.9%). There was one report each of brown urine, cellulitis, conjunctivitis, cyst/nodule formation on thyroid, decrease bilirubin, elevated cholesterol and triglycerides, hematochezia, increased intraocular pressure, irregular menstruation, keloid scar formation, nausea, stunted growth, swelling, and a side effect of unknown type (0.5%). In regard to the three patients who experienced mild depression during usage of isotretinoin, all stated that they believed the depression was caused by external factors. For example, one patient was diagnosed with depression prior to starting treatment and one patient believed the onset was linked to the suicide of a close friend. Blood work abnormalities were noted in 2.1 percent of patients (n=4). Two patients had elevated liver enzyme levels which could be explained by external factors; One patient was binge drinking and one was using large amounts of protein powder. One patient experienced an unexplained increase in cholesterol and triglyceride levels, and one experienced an unexplained decrease in bilirubin. 9.1 percent of patients discontinued isotretinoin and NAL therapy (n=17) due to factors including patient decision or side effects. Of those who discontinued, 23.5 percent opted to restart treatment (n=4).

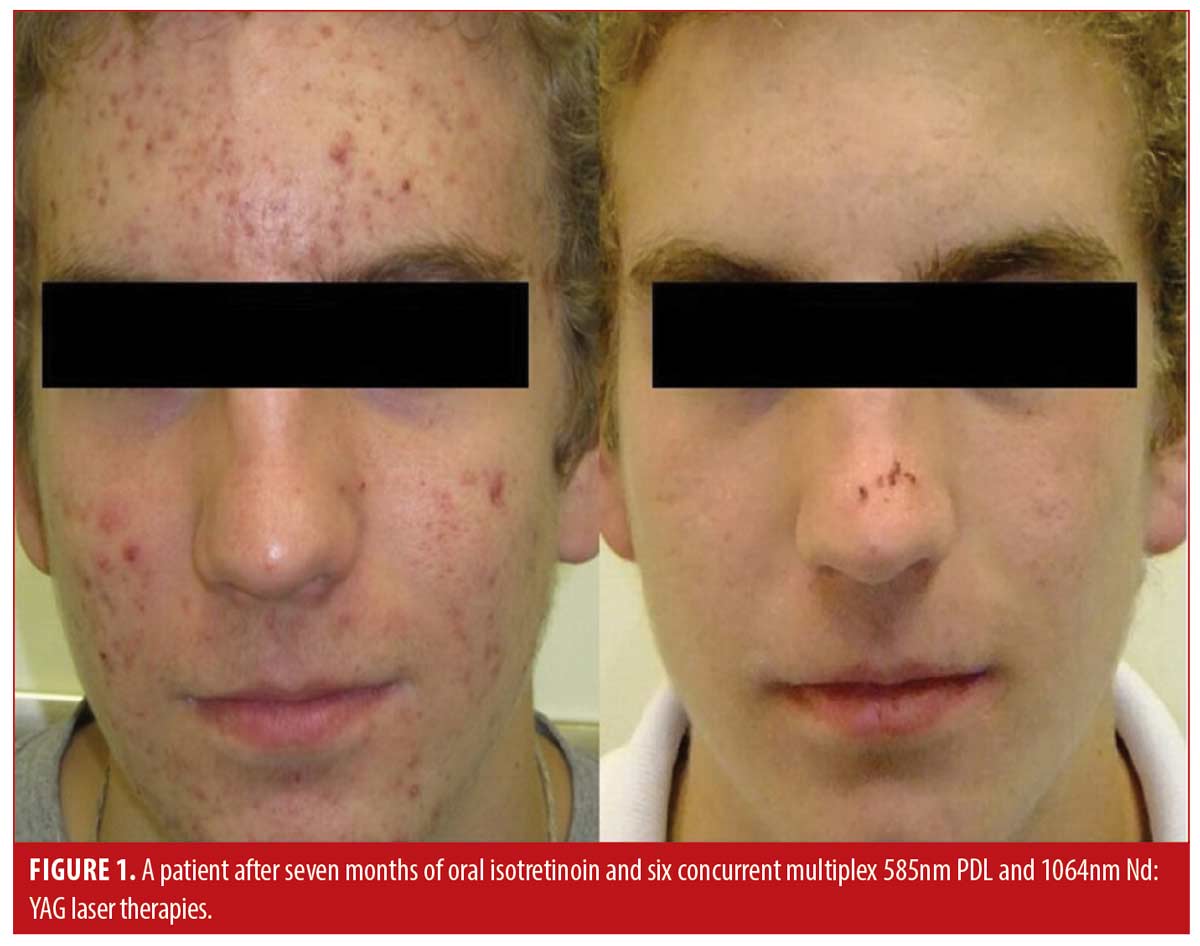

Patient satisfaction was recorded in the chart notes by the clinician or nurse from verbal reports by patients during clinical visits or phone calls. This reporting was initiated by the patient with no standardized questions or response ranges for patient satisfaction. A total of 65.2 percent of patients verbally reported their level of satisfaction (n=122). Out of these patients, all expressed satisfaction with the treatment (100%, n=122). Results of the treatment were reported for 71.1 percent of patients (n=133). Effectiveness data was not reported in 54 patients; thus, the level of improvement is unknown for those patients. Effectiveness was assessed by the clinician based IGA and recorded in the chart notes. There were no standardized lesion count scales used for effectiveness assessments. Of those with available effectiveness data, 99.2 percent of patients (n=132) achieved an IGA score of clear or almost clear, which was maintained up until the most recent follow-up. 0.8 percent of patients (n=1) achieved a mild grading on the IGA scale. No patients were classified as moderate or severe at the end of treatment. Effectiveness and cosmetic results are visually demonstrated in Figures 1, 2 and 3.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to assess the safety of concomitant use of oral isotretinoin and NAL therapy. The most common side effects of eczema and significant dry eyes, skin, and lips are consistent with other isotretinoin and NAL combination studies or isotretinoin studies alone, which display that all or nearly all patients experience dryness.18-19 The low rate reported in this study is due to the clinic’s reporting guidelines for dryness during isotretinoin treatment. All patients are informed by the clinician prior to starting treatment that dryness is a very common side effect of isotretinoin, thus only exceptional dryness is reported and recorded in the patient’s chart. Therefore, side effects related to dryness were thus classified as “significant”, although all patients in the study likely experienced common dryness associated with isotretinoin.

No serious side effects were seen, and the rate of side effects is not greater than other studies reporting values for NAL or isotretinoin treatment alone, or for combination therapy. A large retrospective review of isotretinoin alone (n=3525) reports common side effects including dry lips (100%), xerosis (94.97), facial erythema (66.21%), nosebleeds (47.26%), cheilitis (41.78%), myalgias (38.78%), and itching (38.12%).19 The present combination therapy study displayed much lower reports for all side effects listed, notably erythema (5.2%), nosebleeds (1.4%), cheilitis (0.9%), with no reports of myalgias or itching. Although other studies of isotretinoin treatment alone have shown a mild increase in triglyceride levels in about 25 percent of patients, this was only seen in one patient in the current combination therapy study.20 Some isotretinoin studies showed a possible association with IBS rates while a metanalysis showed no association between isotretinoin and IBS development.21-23 The present study supports no association between isotretinoin and IBS as there were no patient reports of new IBS diagnoses. Also, the present study did not see a high rate of depression or mood changes (n=3; 1.4%). The few patients who did experience depression linked the occurrence to external factors and not to the treatment. One study showed that isotretinoin alone actually aids in improving mood as the patient’s quality of life is increasing as their acne is clearing.24 In comparison, a large cohort isotretinoin study showed that 6.66 percent (n=235) of patients had mood changes and 0.02 percent (n=1) displayed suicidal ideation.19 Furthermore, a study combining 585nm PDL with 1064 nm Nd:YAG without concomitant isotretinoin use reported mild side effects of erythema, dryness, and pain which were also minimally seen in the present study.25

In the past, atypical and poor wound healing was a major concern that led to the suggested wait time of six months between isotretinoin and NAL therapy; however, emerging studies have found this complication to be uncommon and recommend concomitant therapies.11, 12, 15, 17 This study’s data supports these previous studies with a keloid formation rate of 0.5% (n=1). Additionally, the investigator notes that keloid formation is likely a result of the acne itself and not a direct result of isotretinoin or NAL therapy. These results challenge the current AAD recommendations and the suggestion of waiting six months before performing NAL therapy.1,13

Secondary objectives included effectiveness and patient satisfaction. This study found that 99.2 percent of patients with reported effectiveness data experienced a complete or nearly complete clearance of acne lesions on the face as assessed by the clinician until the most recent follow-up. The mean length of follow-up was 902.7 days (SD=870.9 days), with a minimum of 63 and a maximum of 3520 days. Length of follow-up was calculated from start of treatment to the time of last contact with the patient (phone-call or in-person appointments). This clearance rate is higher than studies of isotretinoin alone, one of which reports a 93.9 percent clearance rate.7, 9 The difference could be explained by the fact that the outcome measures were recorded using only the IGA and not in combination with standardized lesion count assessments. Furthermore, 65.2 percent (n=122) of patients reported treatment satisfaction and the remaining patients did not report satisfaction nor dissatisfaction with the treatment. This provides more evidence to offer this combination treatment modality as an effective treatment option.

Limitations. Limitations arise from the retrospective design of this study. Reported effectiveness was based on subjective chart notes and patient satisfaction was only available for patients who voluntarily reported this information. Acne severity was based on IGA and chart notes from clinical examination, however standardized lesion count assessments were not performed. Future studies should be conducted prospectively with objective efficacy, satisfaction, and acne severity scales that allow for direct comparison from baseline to follow-up. The notion of the concomitant isotretinoin and NAL therapy as a better treatment requires a comparator cohort, but none were directly reviewed and controlled for in this study. This retrospective study with no comparator is not able to comment on whether the combination of isotretinoin and NAL is more efficacious that either treatment alone. To further explore this approach to combination therapy, future prospective studies with comparators and larger cohorts incorporating multiple sites with standard dosing and long-term follow up can increase the external validity of the results.

Conclusion

This study further demonstrates the safety of performing NAL therapies during and immediately after isotretinoin use. Current AAD recommendations to wait at least six months to perform laser treatments after discontinuing isotretinoin should be re-examined and Canadian guidelines for concomitant isotretinoin and NAL therapy should be formally defined. The combination therapy also provides patient satisfaction and displays effectiveness, yielding excellent cosmetic results. Isotretinoin in conjunction with multiplex Nd:YAG and PDL therapy delivered through one unique device should be offered as a treatment alternative to other topical and systemic therapies in current guidelines due to its safe, effective, and patient satisfaction yielding results.

References

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945π–973.

- Barankin B, DeKoven J. Psychosocial effect of common skin diseases. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:712–716.

- Kaymak Y, Ilter N. The effectiveness of intermittent isotretinoin treatment in mild or moderate acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(10):1256–1260.

- Ferahbas A, Turan MT, Esel E, et al. A pilot study evaluating anxiety and depressive scores in acne patients treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15(3):153–157.

- Vallerand IA, Lewinson RT, Farris MS, et al. Efficacy and adverse events of oral isotretinoin for acne: A systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):76–85

- Sanclemente G, Acosta JL, Tamayo ME, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for treatment of acne vulgaris: a critical appraisal using the AGREE II instrument. Arch Dermatol Res. 2013;306(3):269–277

- Asai Y, Baibergenova A, Dutil M, et al. Management of acne: Canadian clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 2016;188(2):118–126.

- Kraft J, Freiman A. Management of acne. CMAJ. 2011;183(7).

- Bagatin E, Costa CS. The use of isotretinoin for acne – an update on optimal dosing, surveillance, and adverse effects. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(8): 885–897.

- Gold MH, Goldberg DJ, Nestor MS. Current treatments of acne: Medications, lights, lasers, and a novel 650-μs 1064-nm Nd: YAG laser. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16(3):303–318.

- Prather HB, Alam M, Poon E, et al. Laser safety in isotretinoin use: a survey of expert opinion and practice. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(3):357–363.

- Bernestein LJ, Geronemus RG. Keloid formation with the 585-nm pulsed dye laser during isotretinoin treatment. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(1):111–112.

- Accutane (isotretinoin) capsules label. Federal Drug and Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2002/18662s051lbl.pdf. Updated 2002. Accessed February 23, 2020.

- Waldman A, Bolotin D, Arndt KA, et al. ASDS guidelines task force: Consensus recommendations regarding the safety of lasers, dermabrasion, chemical peels, energy devices, and skin surgery during and after isotretinoin Use. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(10):1249–1262.

- Spring LK, Krakowski AC, Alam M, et al. Isotretinoin and timing of procedural interventions: a systematic review with consensus recommendations. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(8):802–809.

- Mysore V, Mahadevappa OH, Barua S, et al Standard guidelines of care: performing procedures in patients on or recently administered with isotretinoin. J Cutan Aesthet. 2017;10(4):186.

- Mirza FN, Mirza HN, Khatri KA. Concomitant use of isotretinoin and lasers with implications for future guidelines: An updated systematic review. Dermatol Ther. 2020;e14022.

- Ibrahim SM, Farag A, Hegazy R, et al. Combined Low-Dose Isotretinoin and Pulsed Dye Laser Versus standard-Dose Isotretinoin in the Treatment of Inflammatory Acne. Lasers Surg Med. 2021;53(5):603–609.

- Brzezinski P, Borowska K, Chiriac A, et al. Adverse effects of isotretinoin: A large, retrospective review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30(4):e12483.

- Zane LT, Leyden WA, Marqueling AL, et al. A population-based analysis of laboratory abnormalities during isotretinoin therapy for acne vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(8):1016–1022.

- Crockett SD, Porter CQ, Martin CF, et al. Isotretinoin use and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol.2010;105(9):1986–1993.

- Dubeau M-F, Iacucci M, Beck PL, et al. Drug-induced inflammatory bowel disease and IBD-like conditions. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(2):445–456.

- Etminan M, Bird ST, Delaney JA, et al. Isotretinoin and risk for inflammatory bowel disease: a nested case-control study and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(2):216–220.

- Rubinow DR, Peck GL, Squillace KM, et al. Reduced anxiety and depression in cystic acne patients after successful treatment with oral isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17(1):25–32.

- Salah El Din MM, Samy NA, Salem AE. Comparison of pulsed dye laser versus combined pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2017;19(3):149–159.