J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2025;18(9):36–39.

by Nicole Olszewski, LPN, and Christopher G. Bunick, MD, PhD

Ms. Olszewski is with the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Bunick is with the Department of Dermatology and Program in Translational Biomedicine at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

FUNDING: Medical writing and editorial support were supported by Ortho Dermatologics, a division of Bausch Health US, LLC.

DISCLOSURES: Ms. Olszewski served as a Clinical Research Coordinator for AbbVie’s LEVEL-UP clinical trial. Dr. Bunick has served as an investigator and/or consultant for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Apogee, Arcutis, Botanix, Connect BioPharma, Daiichi Sankyo, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, EPI Health/Novan, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Palvella, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, Takeda, Timber, Teladoc, and UCB.

Abstract: Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi)—developed to treat inflammatory and immune-mediated diseases—have shown an increased risk of acne development, especially when used to treat dermatologic conditions. There are no treatment guidelines for JAKi-induced acne. Some of the most efficacious treatments for acne vulgaris (AV) are triple combinations, including benzoyl peroxide (BPO), a topical retinoid, and an oral/topical antibiotic. Fixed-dose, triple-combination clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/adapalene 0.15%/BPO 3.1% (CAB) gel has demonstrated good efficacy, safety, and tolerability in Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials of participants with moderate to severe AV. This case report highlights the possible utility of once-daily CAB for JAKi-induced acne. A 15-year-old female patient was administered the oral JAKi upadacitinib (15mg daily) for 16 weeks to treat atopic dermatitis that inadequately responded to dupilumab. The patient had mild preexisting comedonal and inflammatory facial AV prior to JAKi treatment. Over the first few months of JAKi treatment, her acne worsened to moderate/severe inflammatory acne, with erythema and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The patient applied CAB gel to the face once daily for approximately 20 weeks with substantial acne improvement and without adverse effects. CAB treatment reduced her acne severity to mild to almost clear, and no significant acne-induced sequelae (scarring, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, or erythema) were observed. She continues treatment with both CAB and upadacitinib. Treatment guidelines for AV often recommend oral drugs, such as isotretinoin, for moderate-to-severe acne. This case presented here, however, demonstrates that topical CAB gel can treat moderate to severe JAKi-induced inflammatory acne. Keywords: Janus kinase inhibitor, acne, topical, antibiotic, benzoyl peroxide, retinoid, fixed-dose

Introduction

Drugs that inhibit downstream proinflammatory signaling by members of the JAK family (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2) have been developed to treat inflammatory and immune-mediated diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, psoriatic disease, and atopic dermatitis.1–3 One adverse effect that has been noted with JAK inhibitor (JAKi) treatment is the development of acne.1 Two meta-analyses demonstrated an increased risk of developing acne with JAKi treatment, especially when treating dermatologic conditions.4,5 The role of JAK signaling in acne pathogenesis, however, is unknown.1

JAKi-induced acne has similar clinical characteristics to both acne vulgaris (AV) and acneiform lesions and is often mild or moderate in severity, with predominantly inflammatory lesions.1,6 The American Academy of Dermatology AV treatment guidelines provide strong recommendations for combination treatments that contain topical benzoyl peroxide (BPO), topical retinoids, and/or oral or topical antibiotics for most patients with mild to severe acne and strong recommendations for oral isotretinoin for severe or recalcitrant acne.7 Additionally, a network meta-analysis of over 200 clinical trials of acne treatments found that the most efficacious treatments were oral isotretinoin monotherapy and triple combinations that included BPO, a topical retinoid, and an oral or topical antibiotic.8

Topical clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/adapalene 0.15%/BPO 3.1% (CAB) gel9—the first fixed-dose, triple-combination formulation approved for the treatment of AV—has demonstrated good efficacy, safety, and tolerability in Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials of participants with moderate to severe AV.10,11 CAB has also demonstrated efficacy and safety in patients stratified by sex, age, race, and ethnicity, with improvements in quality of life.12–16 This case report highlights the possible utility of once-daily CAB treatment for JAKi-induced acne.

Case Report

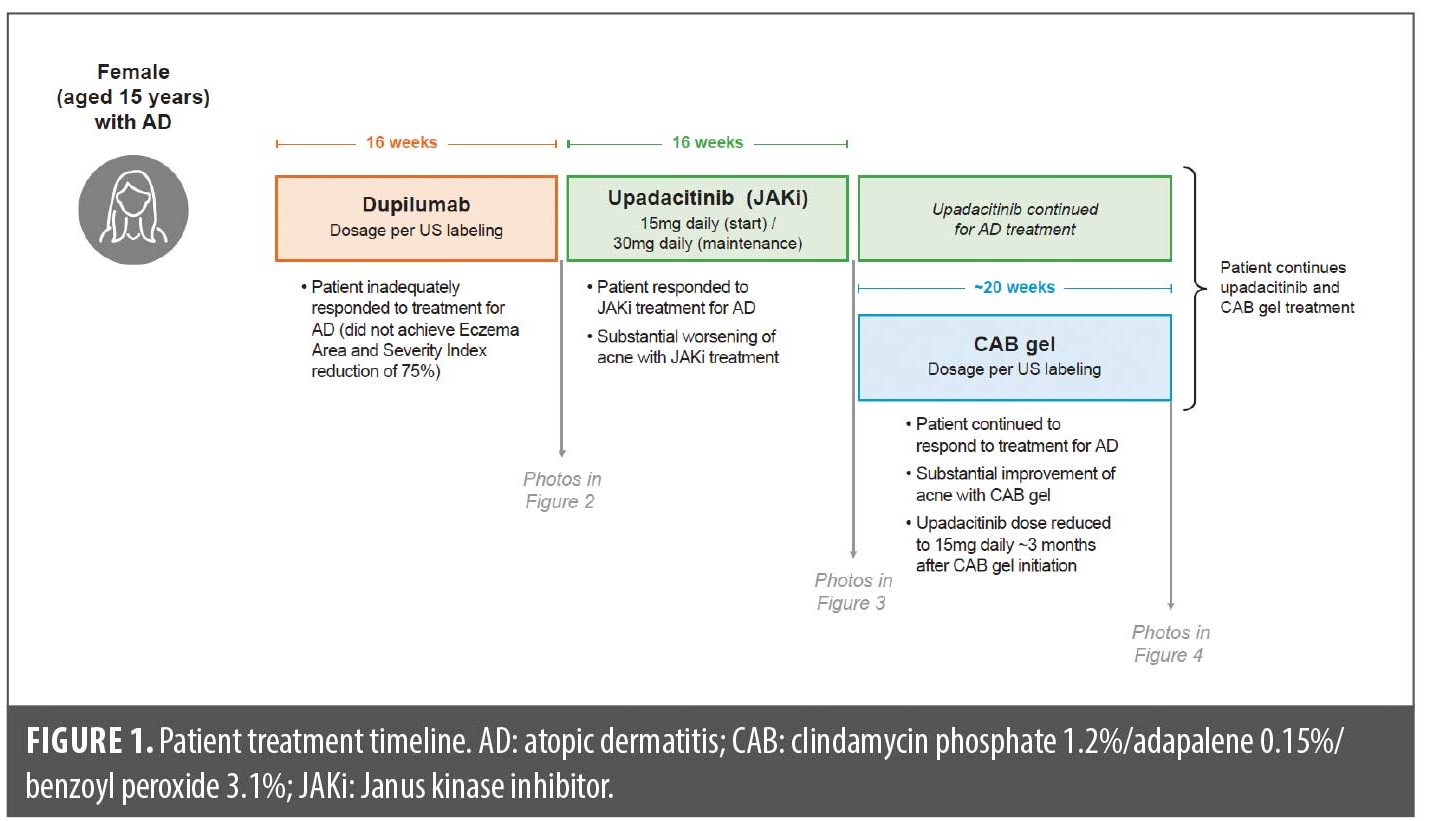

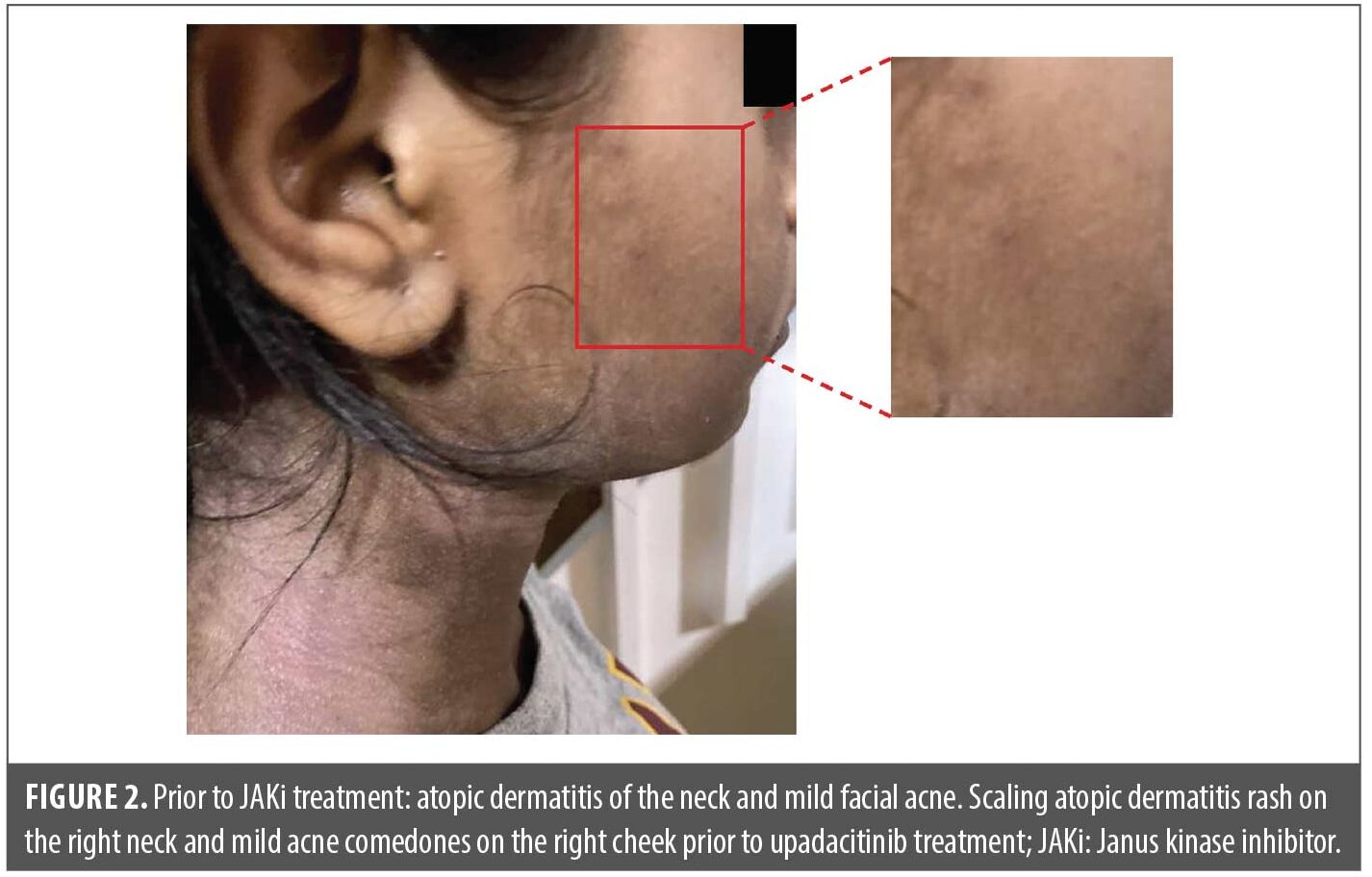

A 15-year-old female patient was administered the oral JAKi upadacitinib starting at 15mg daily for 16 weeks to treat atopic dermatitis that inadequately responded to dupilumab (did not achieve Eczema Area and Severity Index reduction of 75% after 16 weeks of dupilumab [dosage per US labeling] in the LEVEL UP study17; Figure 1). Prior to JAKi treatment, the patient had mild preexisting comedonal and inflammatory facial acne with a few 1–2mm closed comedones or pink papules, primarily on the cheeks and forehead (Figure 2).

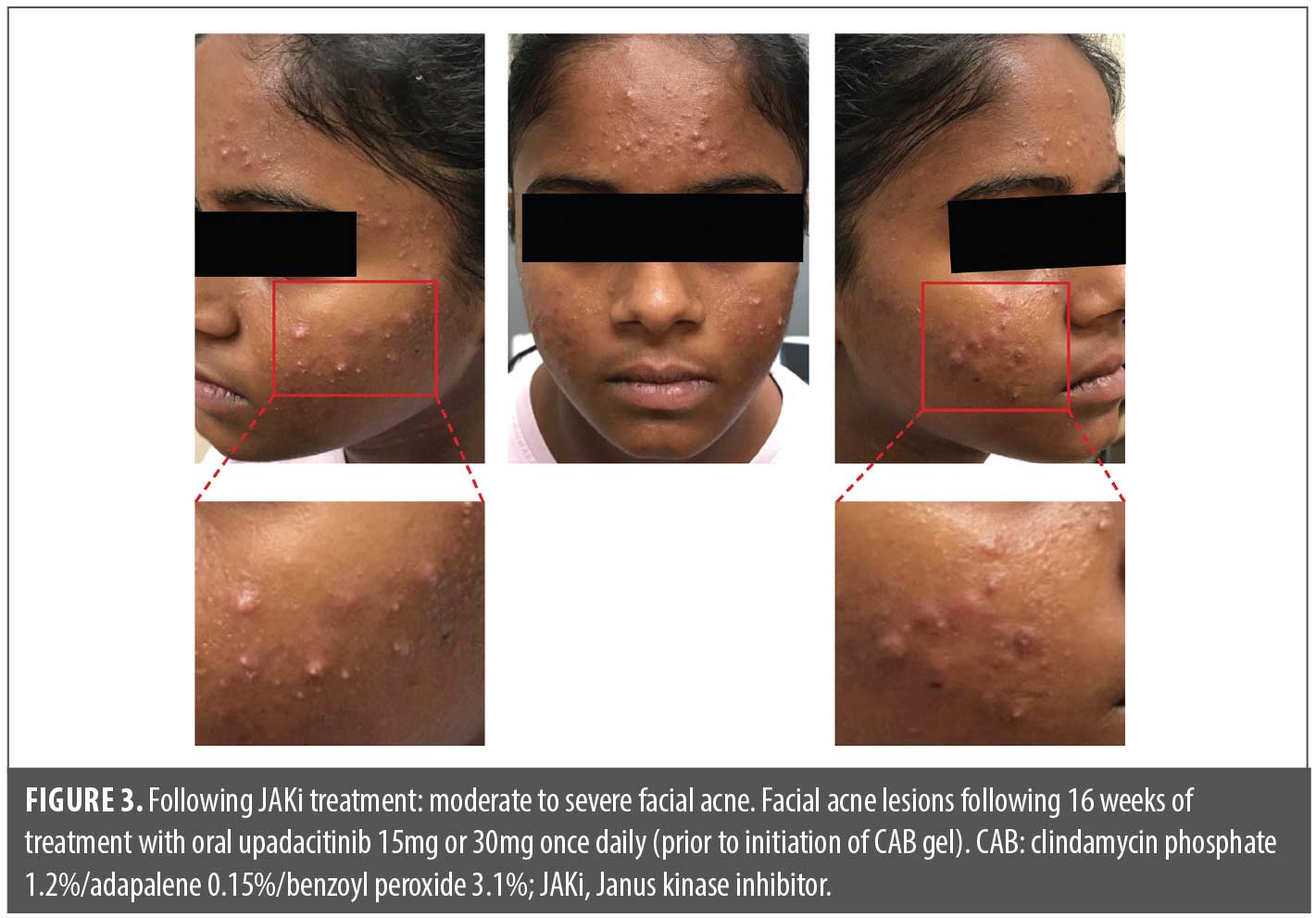

Over the course of the first few months of treatment with the JAKi, her acne worsened substantially, with larger 2–9mm pink to red inflammatory papules, many with prominent pustule formation within, developing on the forehead and cheeks. By the end of the 16-week JAKi treatment period, during which the patient was titrated up to the 30mg upadacitinib daily dose, the patient had moderate-to-severe inflammatory acne, primarily on the cheeks and forehead, but no nodulocystic lesions or scarring (Figure 3). Acne-induced sequelae of erythema and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation were also observed.

The patient applied fixed-dose, triple-combination CAB to the face once daily for five months (~20 weeks) with substantial acne improvement; she continues CAB therapy with benefits and without adverse effects. Overall, CAB treatment reduced acne severity to mild to almost clear, and no significant acne sequelae (scarring, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, or erythema) were observed (Figure 4). CAB gel was the only product used to treat her acne while JAKi treatment was continued throughout. Due to significant improvement in her atopic dermatitis, she underwent a dose reduction in upadacitinib from 30mg daily to 15mg daily approximately three months after CAB initiation; upadacitinib dose reduction occurred after the patient was already improving on CAB. She continues treatment with both CAB and upadacitinib 15mg daily.

Discussion

Studies have shown that there is an increased risk of acne with JAKi treatment, especially when treating dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis.4,5 AV has multiple pathogenic mechanisms of action, including increased sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, inflammatory processes, and Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) proliferation/potential involvement of strains with virulence factors that increase inflammatory capability.7,18 As such, AV treatment guidelines recommend a multipronged approach using combined treatments with multiple mechanisms of action.7 Combinations containing BPO, retinoids, and/or antibiotics are strongly recommended as they each target one or more pathogenesis mechanisms other than sebum production.7 As noted previously, topical triple combinations containing BPO, a retinoid, an antibiotic, or oral isotretinoin monotherapy are some of the most efficacious AV treatments.8 Furthermore, all three agents have anti-inflammatory properties.19

Although JAKi-induced acne has some clinical similarities to AV, the role of JAK signaling in acne development is unclear. JAK1 and JAK3 are overexpressed in acne lesions, which may promote inflammation.20 Recent studies suggest that upadacitinib upregulates estrogen sulfotransferase (SULT1E1) expression in human sebocytes, which can promote triglyceride, squalene, and lipid accumulation and elevated sebum production.21 Patients taking JAKi for dermatologic conditions, however, are more likely to develop acne than those with nondermatologic conditions,4,5,22 demonstrating the complex relationship between JAK signaling and acne development. Therefore, while there currently are no guidelines for treating JAKi-induced acne, AV treatments that reduce inflammation may be optimal.

The patient presented in this case study had substantial worsening of acne with a JAKi treatment, yet the JAKi was highly effective in controlling the patient’s atopic dermatitis when dupilumab could not, making her acne treatment important for sustaining her on an effective atopic dermatitis therapy. Fortunately, her acne decreased considerably in severity over five months of once-daily treatment with fixed-dose, triple-combination CAB gel. In addition, acne-induced inflammatory sequelae, such as erythema and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, were reduced or resolved.

Treatment guidelines for the management of AV often recommend oral drugs, such as isotretinoin, for patients with moderate-to-severe acne.7 Similar recommendations for oral isotretinoin were suggested in a letter to the editor on the management of severe JAKi-induced acne.2 This case presented here, however, demonstrates that topical CAB gel can treat moderate-to-severe JAKi-induced inflammatory acne. This patient not only demonstrated positive responses with once-daily CAB, but treatment was also well tolerated with no reported or visible irritation. In clinical trials, CAB gel has demonstrated significant efficacy (around 50% of participants achieving treatment success and >70% reductions in lesions by Week 12) in different patient populations, with favorable safety and tolerability profiles for the treatment of both moderate and severe AV.10–16

More research is needed to elucidate the roles of JAK signaling and JAKi treatments in acne pathogenesis to determine optimal treatments.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Lynn M. Anderson, PhD, from Citrus Health Group (Chicago, Illinois), and was funded by Ortho Dermatologics (Bridgewater, New Jersey). Ortho Dermatologics is a division of Bausch Health US, LLC. This work was an oral presentation at the 2025 American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting in Orlando, Florida, titled “Update on Antibiotics for Acne and Rosacea” in the Acne and Rosacea Symposium presented on March 10, 2025 by CGB.

References

- Ballanger F, Auffret N, Leccia MT, et al. Acneiform lesions but not acne after treatment with Janus kinase inhibitors: diagnosis and management of Janus kinase-acne. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023;103:adv11657.

- Correia C, Antunes J, Filipe P. Management of acne induced by JAK inhibitors. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15688.

- Shawky AM, Almalki FA, Abdalla AN, et al. A comprehensive overview of globally approved JAK inhibitors. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:1001.

- Martinez J, Manjaly C, Manjaly P, et al. Janus kinase inhibitors and adverse events of acne: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1339–1345.

- Chen BL, Huang S, Dong XW, et al. Janus kinase inhibitors and adverse events of acne in dermatologic indications: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2024;35:2397477.

- Avallone G, Mastorino L, Tavoletti G, et al. Clinical outcomes and management of JAK inhibitor-associated acne in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis undergoing upadacitinib: a multicenter retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1031–1034.

- Reynolds RV, Yeung H, Cheng CE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1006.e1001–1006.e1030.

- Huang CY, Chang IJ, Bolick N, et al. Comparative efficacy of pharmacological treatments for acne vulgaris: a network meta-analysis of 221 randomized controlled trials. Ann Fam Med. 2023;21:358–369.

- Ortho Dermatologics. Cabtreo®. Clindamycin phosphate, adapalene, and benzoyl peroxide gel. Bridgewater, NJ: Ortho Dermatologics; 2023.

- Stein Gold L, Baldwin H, Kircik LH, et al. Efficacy and safety of a fixed-dose clindamycin phosphate 1.2%, benzoyl peroxide 3.1%, and adapalene 0.15% gel for moderate-to-severe acne: a randomized phase II study of the first triple-combination drug. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:93–104.

- Stein Gold L, Lain E, Del Rosso JQ, et al. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/adapalene 0.15%/benzoyl peroxide 3.1% gel for moderate-to-severe acne: efficacy and safety results from two randomized phase 3 trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:927–935.

- Lain ET, Bhatia N, Kircik L, et al. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/adapalene 0.15%/benzoyl peroxide 3.1% gel for male and female acne: phase 3 analysis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2024;23:873–881.

- Baldwin H, Gold LS, Harper JC, et al. Triple-combination clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/adapalene 0.15%/benzoyl peroxide 3.1% gel for acne in adult and pediatric participants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2024;23:394–402.

- Eichenfield LF, Hebert AA, Harper JC, et al. Triple-combination clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/adapalene 0.15%/benzoyl peroxide 3.1% gel for moderate-to-severe acne in children and adolescents. J Drugs Dermatol. 2024;23:1049–1057.

- Callender V, Alexis A, Bhatia N, et al. Efficacy and safety of fixed-dose clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/adapalene 0.15%/benzoyl peroxide 3.1% gel in Black participants with moderate to severe acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2025;18:10–16.

- Callender VD, Baldwin H, Gold LS, et al. Efficacy and safety of fixed-dose clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/adapalene 0.15%/benzoyl peroxide 3.1% gel in Hispanic participants with moderate-to-severe acne: a pooled analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2025;36:2480232.

- Silverberg JI, Bunick CG, Hong HC, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib versus dupilumab in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: week 16 results of an open-label randomized efficacy assessor-blinded head-to-head phase IIIb/IV study (Level Up). Br J Dermatol. 2024;192:36–45.

- Mayslich C, Grange PA, Dupin N. Cutibacterium acnes as an opportunistic pathogen: an update of Its virulence-associated factors. Microorganisms. 2021;9.

- Kurokawa I, Layton AM, Ogawa R. Updated treatment for acne: targeted therapy based on pathogenesis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1129–1139.

- Awad SM, Tawfik YM, El-Mokhtar MA, et al. Activation of Janus kinase signaling pathway in acne lesions. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e14563.

- Kim S-E, Jang Y, Shin K-O, Lee SE. JAK inhibitors increase sebum production in human sebocytes and facial skin of patients with atopic dermatitis: implications for JAK inhibitor-induced acne. Presented at: Society for Investigative Dermatology; May 7-10, 2025; San Diego, CA.

- Thyssen JP, Nymand LK, Maul JT, et al. Incidence, prevalence and risk of acne in adolescent and adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a matched cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:890–896.