J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17(4):18-22

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17(4):18-22

by Valerie D. Callender, MD, FAAD; Valarie M. Harvey, MD; Corey L. Hartman, MD; Mona Gohara, MD; Tanya T. Khan, MD;

William Kwan, MD; Lisa R. Ginn, MD

Dr. Callender is with Callender Dermatology and Cosmetic Center in Glenn Dale, Maryland. Dr. Harvey is with Tidewater Physicians Multispecialty Group in Newport News, Virginia. Dr. Hartman is with Skin Wellness Dermatology in Birmingham, Alabama. Dr. Gohara is with Dermatology Physicians of Connecticut in Branford, Connecticut. Dr. Khan is with Khan Eyelid and Facial Aesthetics in Dallas, Texas. Dr. Kwan is with Lasky Skin Center in Beverly Hills, California. Dr. Ginn is with Skin@LRG in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

FUNDING: This research was funded by an independent grant from SkinCeuticals Inc.

DISCLOSURES: Dr. Callender has served as an investigator, consultant, or speaker for Acne Store, Almirall, Aerolase, AbbVie, Allergan Aesthetics, Avava, Avita Medical, Beiersdorf, Cutera, Dermavant, Eirion Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Epi Health, Galderma, Janssen, Jeune Aesthetics, L’Oréal, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Prollineum, Regeneron, SkinBetter Science, SkinCeuticals, Symatese, Teoxane and UpToDate. All other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article. All authors have received honoraria from SkinCeuticals Inc for participation in the Physicians Council for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. Other than this financial support SkinCeuticals has no input to the work carried out by the council.

ABSTRACT: Objective. There are clinical differences in healthy skin requirements and skin-aging features by race and ethnicity. However, individuals of color are underrepresented in dermatology-related medical information. We sought to gather information from women of color regarding their attitudes about the importance of the prevention of skin aging, available information, and perception of representation in skin-aging prevention information.

Methods. This study involved an observational, cross-sectional, online survey of women aged 18 to 70 years residing in the United States. Participants were placed into one of seven cohorts based on self-reported race/ethnicity. Relative frequencies of responses were compared across cohorts; adjusted logistic regression was used to assess perception of representation in skin-aging prevention information.

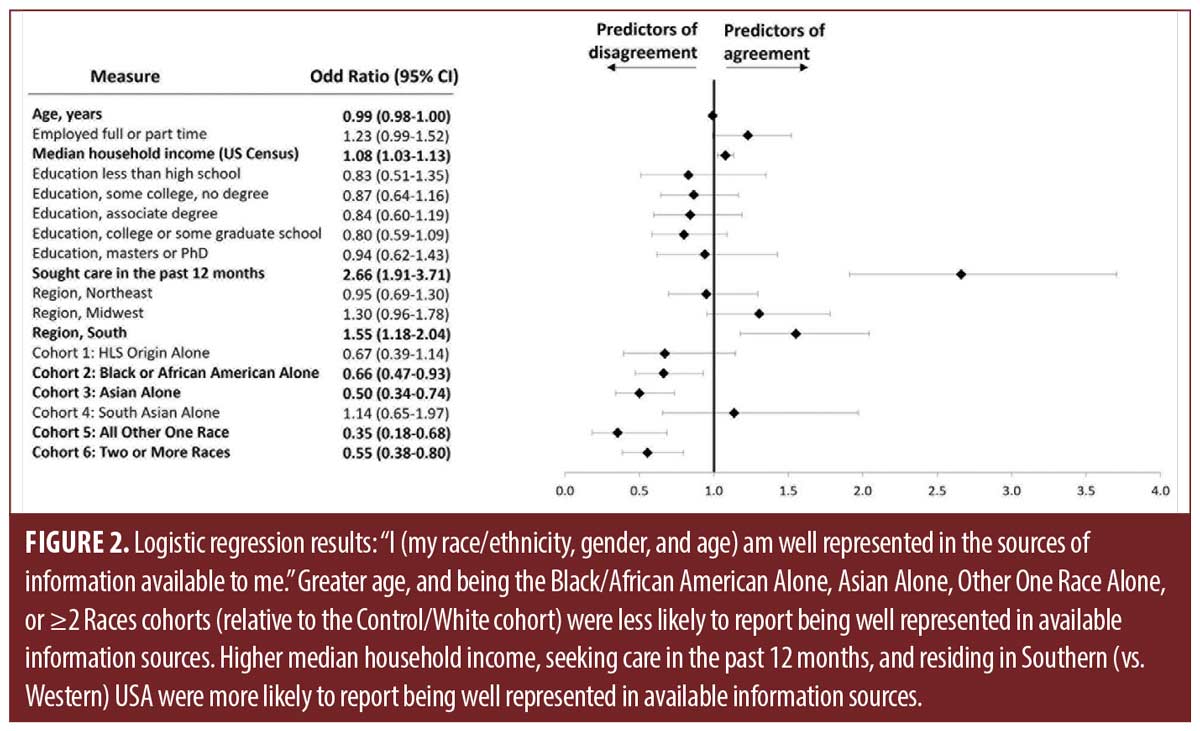

Results. The mean age of the 1,646 participants was 44.4 years. The mean (standard deviation) rating (from 0, “not at all important” to 10, “extremely important”) of the importance of the prevention of skin aging ranged from 7.3 to 8.2 across the seven cohorts. All cohorts reported the most trusted source of information for skin-aging prevention products and treatments was a skin-care professional, but not all cohorts believed they are well represented in available sources of information. Older age, lower median household income, and a race/ethnicity of Black, Asian, “Other,” and “More Than One Race” were less likely to report being well represented.

Limitations. People without internet access could not participate, potentially excluding some older and lower-income groups.

Conclusion. Women of color are less likely to feel represented in available information on the prevention of skin aging.

Keywords. Skin of color, skin aging prevention, patient information, representation, diversity, equity and inclusion

Introduction

According to the US Census Bureau, people of color represent almost 40 percent of the total United States (US) population. However, individuals of color are underrepresented in medical and dermatology-related information. In medical texts, the estimated percentage of images reflecting medium/dark skin tones are only 21 percent and 4.5 percent, respectively;1 in dermatology journals, approximately 16 percent of articles are relevant to skin of color.2 Representation of dark skin at national meetings and in other dermatology resources is also limited.3

A recent literature search reported underrepresentation of skin of color in articles on the use of sunscreen for photoprotection and skin-aging prevention,4 reflecting a larger disparity of women and individuals of color in clinical research.5 Some maintain that these disparities can negatively impact the quality of dermatology care for individuals of color.6 Clinically, there are differences in healthy skin requirements and skin-aging features by race/ethnicity,7,8 as well as in the incidence and presentation of various skin disorders and diseases including dyschromia and some skin cancers.9–14

However, few reports describe how women with skin of color from various ethnicities/races consider prevention of skin aging, their satisfaction with skin-care professionals, and how well their needs are met. We explored skin-aging prevention across ethnicities for US-based women with skin of color.

Methods

Study type and population. This observational, cross-sectional, online survey of US-resident women aged 18 to 70 years was fielded from May 11–25, 2022. Participants confirmed eligibility and gave consent before taking the survey. Each could complete only one survey, and the study design prevented fraudulent submissions.

The survey—developed to include demographic information, skin-aging prevention, perceived importance of prevention, care-seeking behavior, and adequate representation in skin-aging prevention information available—was evaluated by an institutional review board and tested by pilot users.

Participants were split into seven cohorts based on the questions: “Are you of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin?” (Q1) and “Please indicate all racial/ethnic backgrounds with which you identify” (Q2). Cohorts 1 to 6 (Hispanic/Latina/Spanish Alone, Black/African American Alone, Asian Alone, South Asian Alone, All Other One Race, and ≥2 Races) included participants with skin of color; Cohort 7 represented a control group (White Alone); see Supplemental Table 1 for race/ethnicity options and how these were mapped.

Measures collected. The survey collected information including gender, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, employment status, and geographic region. Median household income was imputed from zip codes and US census data.

Outcome measures, determined from survey responses, included the following:

- The importance of skin-aging prevention: “How important is the prevention of skin aging to you?” on a scale from 0 (not at all important) to 10 (extremely important)

- Behavior related to seeking professional care: “Have you ever sought care from a professional for skin aging prevention?” (Yes/No); “What type(s) of professional(s) have you seen for skin aging prevention?”; “What signs of aging prompted you to seek care from a professional?”

- Trust of professionals consulted, using the Wake Forest Physician Trust Scale15—a five-item, one-dimensional scale (0=less trust; 100=more trust)

- Satisfaction with primary skin-care professional: “How satisfied with your primary professional for treating your skin aging prevention needs?” (7 choices from “extremely satisfied” to “extremely dissatisfied”)

- Information received from primary skin-care professional: “Where do you seek information you trust for skin-aging prevention products and treatments?”; “Where would you like to receive information for skin-aging prevention products and treatments?”

- Representation of women of color: “I (my race/ethnicity, gender, and age) am well represented in the sources of information available to me” (strongly agree to strongly disagree); “The skin-aging prevention products and treatments I need are well represented in the sources of information available to me”; “It is easy for me to find information for my specific skin-aging prevention needs.”

Statistical analysis. Descriptive results were presented for outcome measures. Categorical data were described by count and percentage; continuous data by mean and SD. Logistic regression controlling for baseline characteristics (including median household income) was used to assess representation in skin-aging prevention information. All analyses used unweighted data.

Results

Study population and baseline characteristics. The final study population included 1,646 individuals. Cohort 2 (Black/African American Alone) was the largest (31.6%), followed by Cohorts 6 (>1 Race; 21.4%), 3 (Asian Alone; 19.6%), 7 (White Alone; 13.1%), 4 (South Asian Alone; 6.2%), 1 (Hispanic/Latino/Spanish Origin Alone; 5.2%), and 5 (All Other One Race Alone, 2.9%). The mean age across all participants was 44.4 years; Cohort 4 was the youngest (mean age 36.7 years), and the oldest Cohort 5 (46.6 years). Median household income ranged from $52,970 in Cohort 2 to $84,615 in Cohort 4. Other characteristics were similar across cohorts (Table 1).

Outcome measures. On a scale from 0 (not at all important) to 10 (extremely important), the mean (SD) rating of the importance of skin-aging prevention was 7.63 (2.71). All cohorts reported similar average ratings of this importance (range, 7.3–8.2; Table 2). Prevention of fine lines and wrinkles was the most common reason cited by all cohorts (76.1% overall; range, 65.0–85.0% by cohort), followed by laxity (54.8.1% overall; range, 44.2–62.5% by cohort), poor texture (49.6%; 42.5–53.6% by cohort) and dyspigmentation (43.8%; 39.4–48.1% by cohort; Figure 1). Among those who indicated that it was “not important at all” (a rating of 0), reasons given for its unimportance included: not seeing signs of skin aging, costs, and uncertainty about what to buy to prevent skin aging.

Altogether, 17.7 percent of participants indicated that they had ever sought care from a professional for skin-aging prevention (range, 12.5% Cohort 7 to 23.5% Cohort 6); among these, 81.5 percent had done so in the past 12 months. The mean (SD) age when they first sought professional care was 31.1 (11.6) years (range, 28.6 Cohort 2 to 35.9 Cohort 6). Those seeking care within the last year most commonly consulted a dermatologist (37.5% Cohort 5; 73.3% Cohort 1); most were satisfied with their primary skin care professional (84.4% Cohort 2; 100% Cohorts 4 and 5). Among those who had never sought professional help for skin-aging prevention, the most common reasons were cost (51.2%), believing they could manage it themselves (33.6%), and uncertainty where to seek care (22.5%).

Based on ratings of 0=no trust to 10=trust a great deal, all cohorts reported the most trusted source of information for skin-aging prevention products and treatments was a skin-care professional (range of mean [SD], 6.49 [3.11] Cohort 5 to 7.85 [2.24] Cohort 4). Across all participants, 60.6 percent indicated they would “like to receive” information they trust from a skin-care professional, but only 40.0 percent sought such information from a skin-care professional; only 17.7 percent reported that they had ever sought professional care. Cost was the most common disincentive (57.2% overall).

Overall, 58.4 percent agreed/strongly agreed with the statement “I (my race/ethnicity, gender, and age) am well represented in the sources of information available to me.” This was 67.6 percent within Cohort 6 (White Alone), and among individuals of color ranged from 44.7 percent (Cohort 5) to 71.5 percent (Cohort 4). Logistic regression demonstrated that not all cohorts felt well-represented in available sources of information (Figure 2). Older age, and being in Cohorts 2 (Black/African American Alone), 3 (Asian Alone), 5 (All Other One Race Alone), or 6 (>1 Race) were significantly less likely to report being well-represented in available information sources (versus control [White Alone] cohort). Those with a higher median household income, living in Southern US, and who had sought care within the past year were significantly more likely to report that they felt well-represented.

Discussion

The importance of skin-aging prevention was similar across cohorts, as were the most important reasons for seeking skin-aging advice. However, significant differences existed in perceptions regarding how well they are represented in available sources of skin-aging prevention information. This is perhaps not surprising, given the recognized underrepresentation of individuals of color within dermatology information/literature.2–4 Other studies of information and care-seeking behavior for skin care by individuals of color have also demonstrated disparities. A 2020 report16 of acne treatment found that Asian cohorts were less likely than White individuals to seek professional information/care. In another study where individuals were asked about skin-care needs and barriers to the use of dermatologic products, respondents of color more often cited a lack of available products for their skin type as a barrier than did their White counterparts.17

Recently, this imbalance in dermatology information has been highlighted,18,19 noting that underrepresentation of individuals of color can negatively affect quality of care. Previous research has explored the impact of racial disparities on patients’ desire to seek healthcare,20 and on the patient-provider relationship, decisions about treatment, individual adherence, and even outcomes.21

Our study strengths include the large, diverse sample, including underrepresented racial populations; and anonymous responses. However, data were self-reported and required online access. Statistical comparisons were made using an alpha without adjustment for multiple comparisons, resulting in an increased risk of type 1 errors; results involving small sample sizes should be interpreted with caution. Finally, the study occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have impacted outcomes.

To optimize care for ethnically diverse patients, physicians must appreciate patient concerns. Knowing which ethnically diverse groups feel underrepresented helps to initiate this important conversation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Charles M. Boyd, MD and Wendy E. Roberts, MD, both members of the Physicians Council for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, for their contributions to reviewing the draft manuscript. Medical writing support was provided by Craig Solid, PhD, and Beth Sesler, PhD, CMPP, and was funded by SkinCeuticals Inc.

References

- Louie P, Wilkes R. Representations of race and skin tone in medical textbook imagery. Soc Sci Med. 2018;202:38–42.

- Wilson BN, Sun M, Ashbaugh AG, et al. Assessment of skin of color and diversity and inclusion content of dermatologic published literature: An analysis and call to action. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:391–397.

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687–690.

- Boyd CM, Callender VD, Ginn LR, et al. Skin of color is underrepresented in the medical literature describing use of sunscreen for photoprotection and to prevent skin aging – preliminary quantitative results from a literature search. Skin of Color Update; September 9, 2022; Sheraton New York Times Square Hotel, New York.

- Bierer BE, Meloney LG, Ahmed HR, et al. Advancing the inclusion of underrepresented women in clinical research. Cell Rep Med. 2022;3:100553.

- Lester JC, Taylor SC, Chren MM. Under-representation of skin of colour in dermatology images: not just an educational issue. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1521–1522.

- Chan IL, Cohen S, da Cunha MG, et al. Characteristics and management of Asian skin. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:131–143.

- Venkatesh S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Aging in skin of color. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:351–357.

- Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748–762.

- Higgins S, Nazemi A, Chow M, et al. Review of nonmelanoma skin cancer in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:903–910.

- Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519–526.

- Kang SJ, Davis SA, Feldman SR, McMichael AJ. Dyschromia in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:401-406.

- Rendon MI. Dermatological concerns in the Latino population. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:s111.

- Zakhem GA, Pulavarty AN, Lester JC, et al. Skin cancer in people of color: A systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:137–151.

- Dugan E, Trachtenberg F, Hall MA. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:64.

- Mehta M, Kundu RV. Racial differences in treatment preferences of acne vulgaris: A cross-sectional study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:802.

- Geisler A, Masub N, Toker M, et al. Skin of color skin care needs: Results of a multi-center-based survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:709–711.

- Kaundinya T, Kundu RV. Diversity of skin images in medical texts: Recommendations for student advocacy in medical education. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:23821205211025855.

- Onyekaba G, Taiwò Née Ademide Adelekun D, Lipoff JB. Skin of color representation in dermatology must be intentionally rectified. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:e43–e44.

- Armstrong-Mensah E, Rasheed N, Williams D, et al. Implicit racial bias, health care provider attitudes, and perceptions of health care quality among African American College students in Georgia, USA. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022.

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e60–76.