J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(5):E82–E86.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(5):E82–E86.

by Ayman Grada, MD; Suraj Muddasani, MD; Alan B. Fleischer Jr., MD; Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD; and Gabrielle M. Peck, BA

Dr. Grada is with Grada Dermatology Research in Chesterbrook, Pennsylvania. Dr. Muddasani is with the College of Medicine at University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, Ohio. Dr. Fleischer is with the Department of Dermatology at the University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, Ohio. Dr. Feldman is with the Department of Dermatology at Wake Forest School of Medicine, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Ms. Peck is with the College of Medicine at the University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, Ohio.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: Dr. Fleischer is a consultant for Boerhringer-Ingelheim, Incyte, Qurient, SCM Lifescience, Syneos, Almirall, and Trevi. He is an investigator for Galderma and Trevi. He has no other potential conflicts including honoraria, speakers’ bureau, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants, patents filed, received, pending, or in preparation, royalties, or donation of medical equipment. Dr. Feldman received research, speaking and/or consulting support from Arcutis, Helsinn, Amgen, Galderma, Almirall, Alvotech, Leo Pharma, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Ortho Dermatology, Abbvie, Samsung, Janssen, Lilly, Menlo, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Advance Medical, Sun Pharma, Informa, UpToDate and National Psoriasis Foundation. He is founder and majority owner of www.DrScore.com and founder and part owner of Causa Research, a company dedicated to enhancing patients’ adherence to treatment. Dr. Grada is the former Head of R&D and Medical Affairs at Almirall US.

ABSTRACT: Objective. We sought to determine the outpatient visit rates for the five most common skin conditions among dermatologists and non-dermatologists.

Methods. We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional analysis using the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey between 2007 and 2016, the most recent years available.

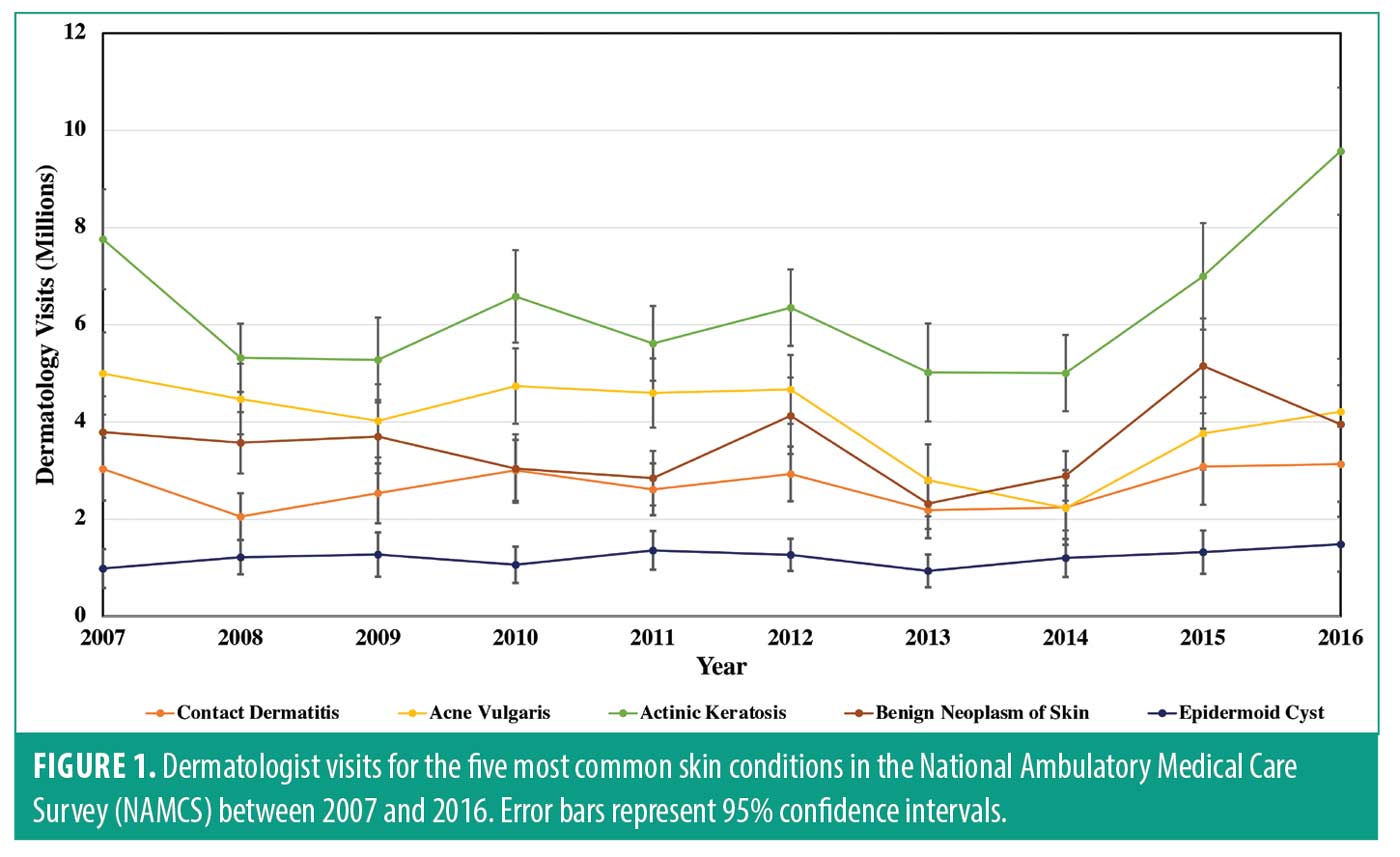

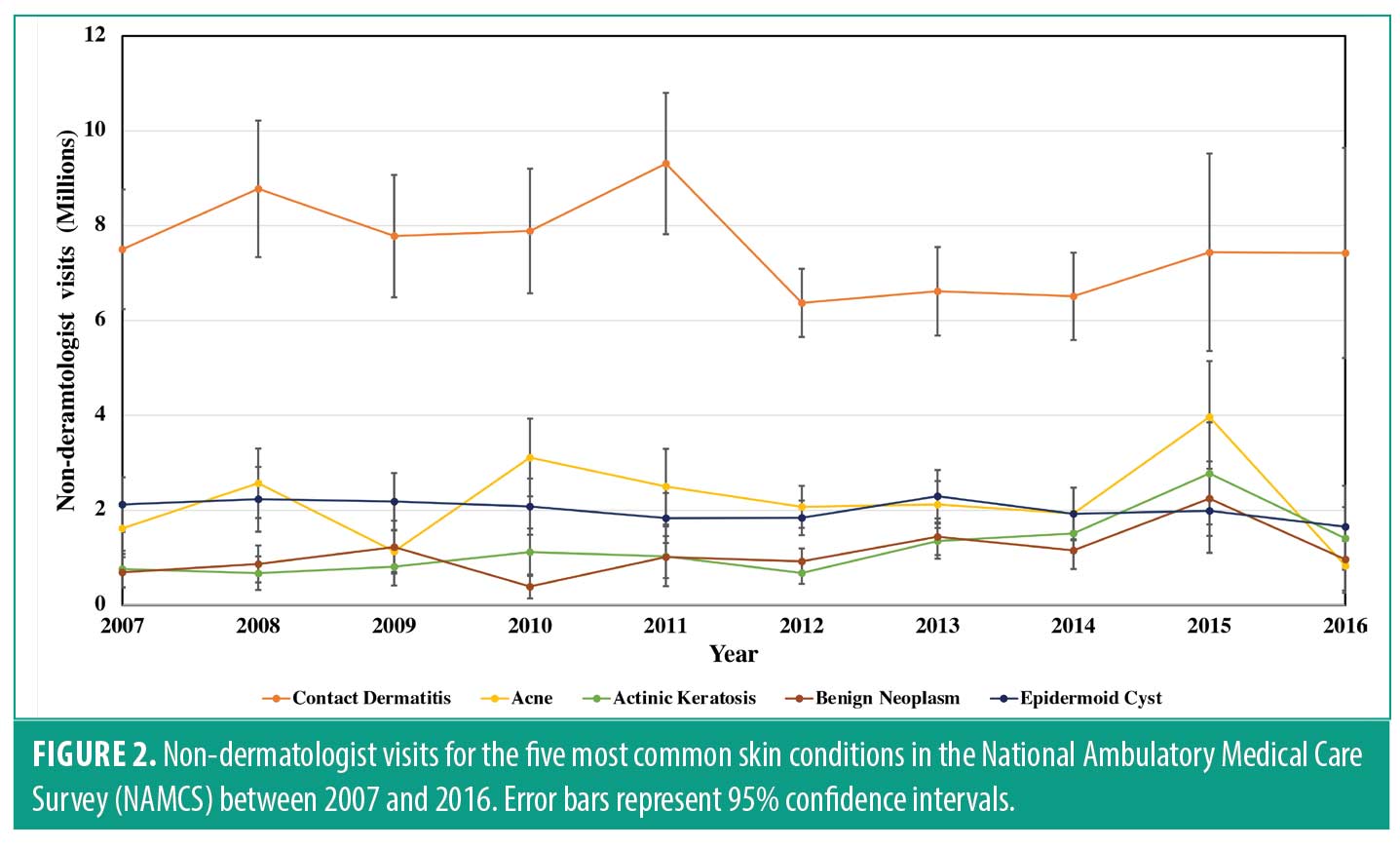

Results. The five most common skin diagnoses among all medical specialties were contact dermatitis, acne vulgaris, actinic keratosis, benign neoplasm of the skin, and epidermoid cyst, respectively. Actinic keratosis followed by acne vulgaris and benign neoplasm of skin were the three most common visit diagnoses among dermatologists, whereas contact dermatitis, acne vulgaris, and epidermoid cyst were the most common among non-dermatologists. Overall, visits for the five most common skin conditions seen by dermatologists and non-dermatologists remained constant over the study interval.

Limitations. Misclassification bias could be impacting the results of this study. Additionally, the NAMCS samples only non-hospital based outpatient clinicians, and thus cannot describe hospital-based outpatient visits or inpatient hospital care.

Conclusion. Visits for contact dermatitis, acne, actinic keratosis, benign neoplasm of the skin, and epidermoid cysts have remained constant over the last ten years. These conditions represent the most common diagnoses of the skin at both dermatologists and non-dermatologists outpatient visits. Non-dermatologists continue to see almost half of visits for the five most common skin diagnoses. Patients are often referred from the primary care setting for growths of skin and skin lesions; thus, it is not surprising that actinic keratosis has remained the most common diagnosis among dermatologist and benign neoplasm the third most common dermatologic diagnosis.

Keywords: contact dermatitis, acne, actinic keratosis, benign neoplasm, epidermoid cyst, sebaceous cyst, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS)

Skin conditions are the most common reason for a new presentation to a primary care physician.1 This is not surprising, given that one third of the United States population is affected by at least one skin condition at any given time.2,3 Although some may obtain care from dermatologists, many patients have their skin diseases treated by general practitioners in the outpatient setting.1,4

The most common dermatologic diagnoses by non-dermatologists and dermatologists between the years 2001 to 2010 has been characterized using the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). Acne, actinic keratosis, and non-melanoma skin cancer were among the top diagnoses by dermatologists.5

However, the most common skin conditions seen recently in the outpatient setting is not well characterized.4,6 As burden of skin disease in the United States is constantly changing, it is important to attain current estimates for visit rate frequency for skin conditions. Thus, we aimed to determine visit rates for the five most common skin conditions in the NAMCS among dermatologists and non-dermatologists over the last decade.

Methods

The NAMCS is an ongoing survey which provides objective information about the use of ambulatory medical services in the United States. The survey is conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The NAMCS surveys a large, generalizable sample of physicians and non-physician providers and has achieved high response rates of up to 77%.7,8 Hence, our research group and others have successfully utilized the NAMCS to understand and characterize trends in outpatient dermatology visits.7,9,10

A three-stage, random selection process is employed by the NAMCS. First, 112 geographic areas in the U.S. are sampled. Physicians and non-physician providers are then selected from these geographic areas using American Medical Association (AMA) and American Osteopathic Association (AOA) master files. A one-week period from each randomly selected provider is sampled and a proportion of visits are systematically chosen. The visit sampling rate is determined by the number of patients seen per practice, ranging from 20% for busy practices to 100% for less busy practices. Non-federally employed, office-based physicians and non-physician providers (i.e., nurse practitioners and physician assistants) document patient demographic information, diagnoses, medications prescribed, services and procedures performed for each visit sampled.

To estimate nationally representative values, weighting factors are assigned to each visit to account for the time and region that a visit occurred.11,12 Weighing factors are derived using a multistage estimation procedure which includes (i) inflation by reciprocals of the probabilities of selection, (ii) nonresponse adjustment, (ii) a ratio adjustment to fixed totals, and (iv) weight smoothing.13

The NAMCS captures up to five diagnoses reported at each visit. This accounts for the fact that patients are often given multiple diagnoses at a single visit. We evaluated the five most commonly diagnosed skin conditions in the NAMCS from 2007 to 2016, the most recent years available. NAMCS data from 2017 has not been published, and 2018 data had low response rates and did not include stratification by specialty; thus we excluded this data from our study.

The five most commonly diagnosed conditions of the skin between 2007 and 2016 had the International Classification of Disease 9th modification (ICD-9) codes: 216.9, 692.9, 702, 706.1, and 706.2, and ICD-10 codes: D23.9, L25.9, L57.0, L70.0, and L72.3. These represent “contact dermatitis not otherwise specified (NOS),” “acne vulgaris,” “actinic keratosis,” “benign neoplasm of skin” and “epidermoid cyst.” Sample weights were applied to derive estimates for each diagnosis.

We also evaluated the visit rate in which a skin exam was performed by both dermatologists and non-dermatologists. Physicians and non-physician providers not only document medications prescribed in the NAMCS survey, they also document non-medication services performed such as skin exams. Thus, we used the NAMCS defined variable “skin” to identify if a skin exam was conducted at a visit.

Imputed race and ethnicity data was grouped as White, Black, Asian, and Hispanic. We conducted our analysis using the survey procedures of SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.). Linear regression models were generated using SAS PROC SURVEYREG. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Only one Institutional Review Board (IRB) must review the NAMCS and the NCHS Ethics Review Board (ERB), which has authority to review under the Regulations for the Protection of Human Subjects, has done so. Therefore, our research group did not need to attain IRB approval from our institution.14

Results

The five most frequent skin diagnoses at outpatient visits among all medical specialties were contact dermatitis not otherwise specified, acne vulgaris, actinic keratosis, benign neoplasm of the skin, and epidermoid cyst. Females comprised 53.7% (95% CI, 52.4-55.0) and males comprised 46.3% (95% CI, 45.0-47.6) of all visits. The median age of patients attending visits for the five most common skin conditions was 46.5 (95% CI, 45.2-47.7) years. Overall, the total number of visits for the five most common skin conditions by dermatologists and non-dermatologists remained unchanged over the study interval (p<0.001).

Of the five most common skin diagnoses reported in the data set, the most common visit diagnosis among dermatologists was actinic keratosis, followed by acne vulgaris, benign neoplasm of skin, contact dermatitis not otherwise specified, and epidermoid cyst, respectively (Figure 1). These differences are within the 95% confidence interval. Among dermatologists, visit rates for actinic keratosis (p=0.0077) were increasing over the study interval, whereas acne vulgaris (p=0.0008) visit rates were decreasing. Dermatologist visit rates for benign neoplasm of skin and epidermoid cyst remained unchanged (Table 1). The number of skin exams completed by dermatologists was decreasing over the study interval by an estimated 9,600 visits per year (p<0.05).

Among non-dermatologists, the most common visit skin diagnosis over the study interval was contact dermatitis. This difference was outside of the 95% confidence interval. The next most common visit diagnosis was acne vulgaris followed by epidermoid cyst, actinic keratosis, and benign neoplasm of skin (Figure 2). These differences were with the 95% study interval. Contact dermatitis (p<0.0001) and benign neoplasm of skin (p=0.0012) experienced increased visit rates among non-dermatologists. Acne, actinic keratosis, and benign neoplasm visit rates remained constant (Table 1). Skin exam rates for non-dermatologists remained unchanged (p=0.7).

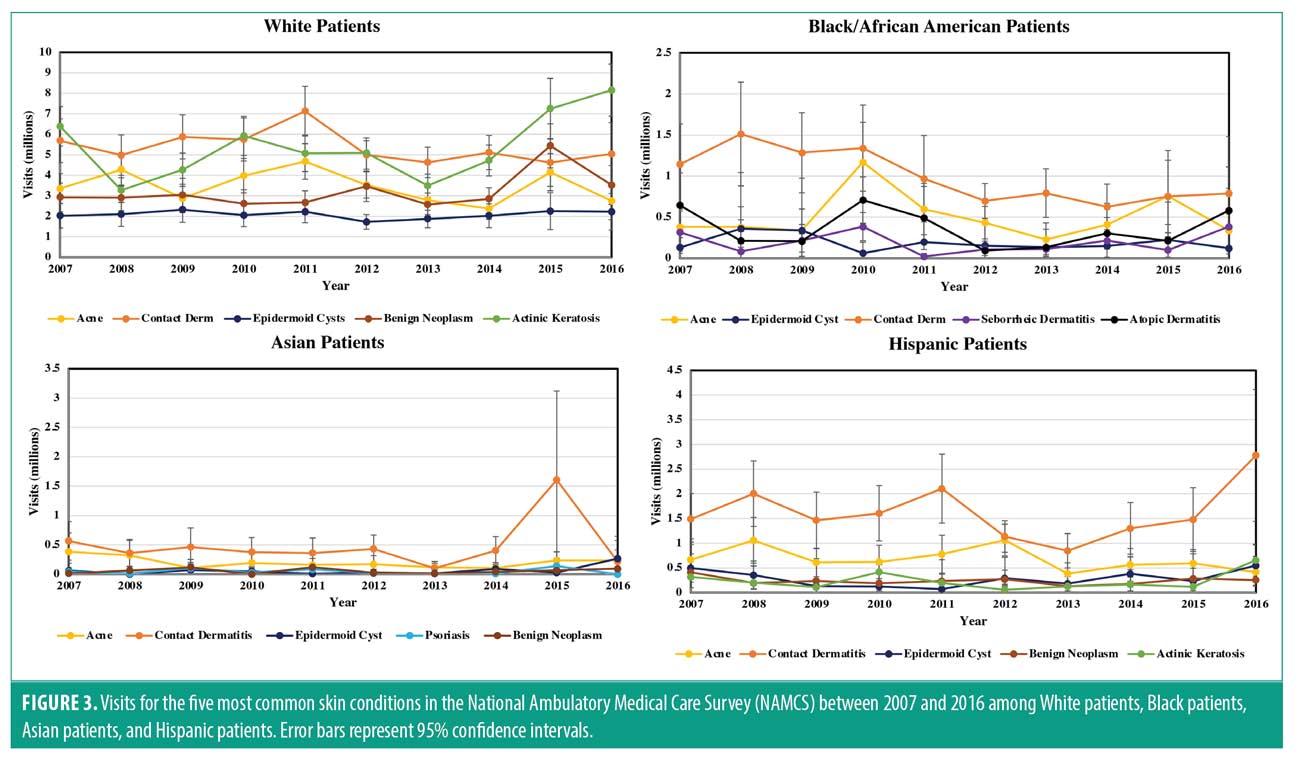

When stratifying by race and ethnicity, contact dermatitis was the most common visit diagnosis among all race and ethnicity groups. Seborrheic dermatitis and atopic dermatitis were included in the five most common diagnoses for Black patients, replacing actinic keratosis and benign neoplasm of skin. Among Asian patients, psoriasis replaced actinic keratosis among the leading five diagnoses. Hispanic and White patients had the same leading five diagnoses as the entire population (Figure 3).

Discussion

While we have identified some changes, visits for the five most common diagnoses of the skin have remained constant over the study interval for both dermatologists and non-dermatologists. Contact dermatitis, acne, benign neoplasm of the skin, and actinic keratosis have remained common visit diagnoses among the U.S. population over the last ten years. Clear clinical guidelines for treatment and prevention should be established by experts in the field of dermatology to help guide non-dermatologists in management of these common conditions. Non-dermatologists continue to see almost half of the five most common skin diagnoses. It may be valuable for dermatology education for non-dermatologists to focus on these conditions as they are commonly encountered.

Actinic keratosis and benign neoplasm of skin. Actinic keratosis was the most common visit diagnosis and benign neoplasm of the skin was the third most common visit diagnosis for dermatologists. Patients are often referred from the primary care setting for growths of the skin and skin lesions; thus these diagnoses are common among dermatologists.15,16 The visit rates to dermatology for actinic keratosis were increasing over the study interval, whereas visit rates for benign neoplasms were unchanged over the study interval. Non-dermatologists saw increased visit rates for benign neoplasm of the skin, while actinic keratosis visit rates remained constant. This increased visit rate cannot be explained by non-dermatologists completing more skin exams, as the visit frequency in which skin exams were performed did not change over the study interval.

Acne. Although acne was the second most common visit diagnosis seen by dermatologists, its frequency of visits per year declined over the study interval. Overall, consultation rates from primary care providers for acne are decreasing. The mainstays of acne treatment have remained relatively unchanged over the study interval.19 Topical adapalene, an effective and well tolerated treatment for mild-to-moderate acne, is available over the counter, and potentially this may have reduced the need to visit the dermatologist.20 Additionally, the increasing implementation of clinical guidelines for treatment of acne vulgaris may have decreased the necessity for dermatologist visits for acne.21,22

Contact dermatitis. Contact dermatitis was the most common diagnosis among non-dermatologists and visit rates to non-dermatologists for the condition are increasing. Contact dermatitis is a very common condition, estimated to affect 20% of the population at one point in their life.23 Contact dermatitis is readily identified in the primary care setting and can often, but not always, be managed with avoidance of the causative agent and a topical agent. Non-dermatologists may be utilizing contact dermatitis not otherwise specified to describe a range of different forms of dermatitis. Additionally, allergists are specialists commonly involved in the management of this skin condition. These factors explain why this condition is more commonly managed by non-dermatologists.24

Epidermoid cysts. Epidermoid cysts were among the leading five diagnoses among all dermatologists and non-dermatologists and among all race and ethnicity groups. Despite epidermoid cysts being considered benign, it is a common skin diagnosis in the United States.25,26

Race and ethnicity stratification. Actinic keratosis was not included in the leading five visit diagnoses for Black and Asian patients. The relationship between increasing amount of melanin in the skin and protection against ultraviolet (UV) induced skin damage is well established. Thus, it understandable patients with increased melanin in the skin are less likely to visit for skin lesions caused by UV damage.27

Atopic dermatitis has been shown to occur more frequently in Black patients compared to White patients, therefore it is unsurprising that this visit diagnosis was common among this population.28 Although psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis were included in the leading five diagnoses among Asian and Black patients respectively, this finding likely does not reflect increased prevalence among these populations.29,30

Limitations. Misclassification bias could be impacting the results of this study; while contact dermatitis was the most common diagnosis among non-dermatologists, non-dermatologists may be diagnosing contact dermatitis for patients who have another skin condition. A limitation of the NAMCS is that it does not provide a direct estimate of the prevalence of a condition in the population, only estimates of visits to outpatient-based physicians for those conditions. This is especially true for skin disease, as many people do not consult physicians for skin abnormalities.3 Another limitation of this study was that in order to estimate the change in number of visits per year it necessitated unassigning and reassigning the weighting variable. Thus, these estimates better indicate directionality and magnitude rather than representing detailed estimates of high accuracy. Finally, publication delays in the NAMCS limit our ability to characterize visit rates over the last few years.

Conclusion

Visit rates for contact dermatitis, acne, actinic keratosis, benign neoplasm of the skin, and epidermoid cysts have remained constant over the last ten years. These conditions represent the most common diagnoses of the skin at both dermatology and non-dermatology appointments.

References

- Roux E Le, Edwards PJ, Sanderson E, Barnes RK, Ridd MJ. The content and conduct of GP consultations for dermatology problems: A cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(699):E723–30.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, Bolliger IW, Dellavalle RP, Margolis DJ, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: An analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(6): 1527–1534.

- Tizek L, Schielein MC, Seifert F, Biedermann T, Böhner A, Zink A. Skin diseases are more common than we think: screening results of an unreferred population at the Munich Oktoberfest. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2019 Jul 19;33(7):1421–1428.

- Verhoeven EWM, Kraaimaat FW, Van Weel C, Van De Kerkhof PCM, Duller P, Van Der Valk PGM, et al. Skin diseases in family medicine: Prevalence and health care use. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):349–54.

- Wilmer EN, Gustafson CJ, Ahn CS, Davis SA, Feldman SR, Huang WW. Most common dermatologic conditions encountered by dermatologists and nondermatologists. Cutis. 2014 Dec;94(6):285–292.

- Hahnel E, Lichterfeld A, Blume-Peytavi U, Kottner J. The epidemiology of skin conditions in the aged: A systematic review. J Tissue Viability. 2017 Feb 1;26(1):20–28.

- Ahn CS, Allen MM, Davis SA, Huang KE, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR. The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: A resource for understanding the outpatient dermatology treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014 Dec;25(6):453–458.

- Arafa AE, Anzengruber F, Mostafa AM, Navarini AA. Perspectives of online surveys in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:511–520.

- Weissman AS, Ranpariya V, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR. How the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey has been used to identify health disparities in the care of patients in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021 Oct;113(5):504–514.

- Lipner SR, Hancock JE, Fleischer AB. The ambulatory care burden of nail conditions in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32(5):517–20.

- CDC. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/datasets_documentation_related.htm.

- CDC. 2018 Micro-Data File Documentation NAMCS [Internet]. 2018. Available from: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NAMCS

- NAMCS/NHAMCS – Estimation Procedures [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 13]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_estimation_procedures.htm

- NAMCS/NHAMCS – HIPAA Privacy Rule Questions and Answers for NAMCS [Internet]. [cited 2021 Dec 9]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/namcs_hipaa_privacy.htm

- Lowell BA, Froelich CW, Federman DG, Kirsner RS. Dermatology in primary care: Prevalence and patient disposition. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(2):250–5.

- Barnett ML, Song Z, Landon BE. Trends in physician referrals in the United States, 1999-2009. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Jan 23;172(2):163–70.

- Tripp MK, Watson M, Balk SJ, Swetter SM, Gershenwald JE. State of the science on prevention and screening to reduce melanoma incidence and mortality: The time is now. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016 Nov 12;66(6):460–80.

- de Oliveira ECV, da Motta VRV, Pantoja PC, Ilha CS d. O, Magalhães RF, Galadari H, et al. Actinic keratosis–review for clinical practice. Int J Dermatol. 2019 Apr;58(4):400–407.

- Habeshian KA, Cohen BA. Current issues in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Pediatrics. 2020 May 1;145(2):S225–30.

- Thiboutot DM, Shalita AR, Yamauchi PS, Dawson C, Kerrouche N, Arsonnaud S, et al. Adapalene gel, 0.1%, as maintenance therapy for acne vulgaris: A randomized, controlled, investigator-blind follow-up of a recent combination study. Arch Dermatol. 2006 May;142(5):597–602.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, Alikhan A, Baldwin HE, Berson DS, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 May 1;74(5):945-973.e33.

- Liu KJ, Hartman RI, Joyce C, Mostaghimi A. Modeling the effect of shared care to optimize acne referrals from primary care clinicians to dermatologists. JAMA Dermatology. 2016 Jun 1;152(6):655–660.

- Peiser M, Tralau T, Heidler J, Api AM, Arts JHE, Basketter DA, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: Epidemiology, molecular mechanisms, in vitro methods and regulatory aspects. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012 Mar;69(5):763–781.

- Švecová D, Nemsovska J. Contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2015. 1–137

- Ganguli I, Shi Z, John Orav E, Rao A, Ray KN, Mehrotra A. Declining use of primary care among commercially insured adults in the United States, 2008 –2016. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Feb 18;172(4):240–247.

- Weir CB, St.Hilaire NJ. Epidermal Inclusion Cyst. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30335343

- Laberge GS, Duvall E, Grasmick Z, Haedicke K, Galan A, Leverett J, et al. Focus: Skin: Recent Advances in Studies of Skin Color and Skin Cancer. Yale J Biol Med. 2020 Mar 1;93(1):69.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—Variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018 Apr 1;27(4):340–57.

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in Skin of Color: Insights into the Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Genetics, Quality-of-Life Impact, and Treatment of Psoriasis in Non-White Racial/Ethnic Groups. Am J Clin Dermatology. 2017 Dec 5;19(3):405–423.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, Huang W, Pichardo-Geisinger RO, McMichael AJ. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: An analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatology. 2012 Apr 1;11(4):466–73.