J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(6):20–24.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(6):20–24.

by James Del Rosso, DO; Linda Stein Gold, MD; Nicholas Squittieri, MD; and

Diane Thiboutot, MD

Dr. Del Rosso is with Touro University Nevada in Henderson, Nevada. Dr. Stein Gold is with Henry Ford Medical Center in Detroit, Michigan. Dr. Squittieri is with Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc., in Princeton, New Jersey. Dr. Thiboutot is with Penn State Hershey Dermatology in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

FUNDING: The studies were funded by Cassiopea S.p.A. Manuscript preparation and editorial support were provided by Dana Lengel, PhD, of AlphaBioCom, a Red Nucleus company, and funded by Sun Pharma.

DISCLOSURES: JDR has served as a research investigator, consultant, and/or speaker for Allergan, Almirall, Arcutis, Bayer, Bausch Health (Ortho Dermatologics), Biorasi, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cassiopea S.p.A., Cutera, Dermavant, Dr. Reddy, EPI Health, Evommune, Ferndale, Galderma, JEM Health, Journey, Johnson & Johnson, LEO Pharma, L’Oreal, Mayne Pharma, Sebacia, Sol-Gel, Sun Pharma, and Vyne. LSG is an employee of the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, Michigan, which received compensation from Cassiopea S.p.A. for study participation; she has also received personal fees for advisory, speaking, consulting, research, and/or other services with Almirall, Foamix, Galderma Laboratories, Novartis, Sol-Gel, and Sun Pharma. NS is an employee of Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc. DT served in the past as a consultant to Cassiopea, Inc., and is an employee of the College of Medicine at The Pennsylvania State University in Hershey, which received compensation from Cassiopea S.p.A. for study participation; she has also received honoraria from Galderma Laboratories and Novartis.

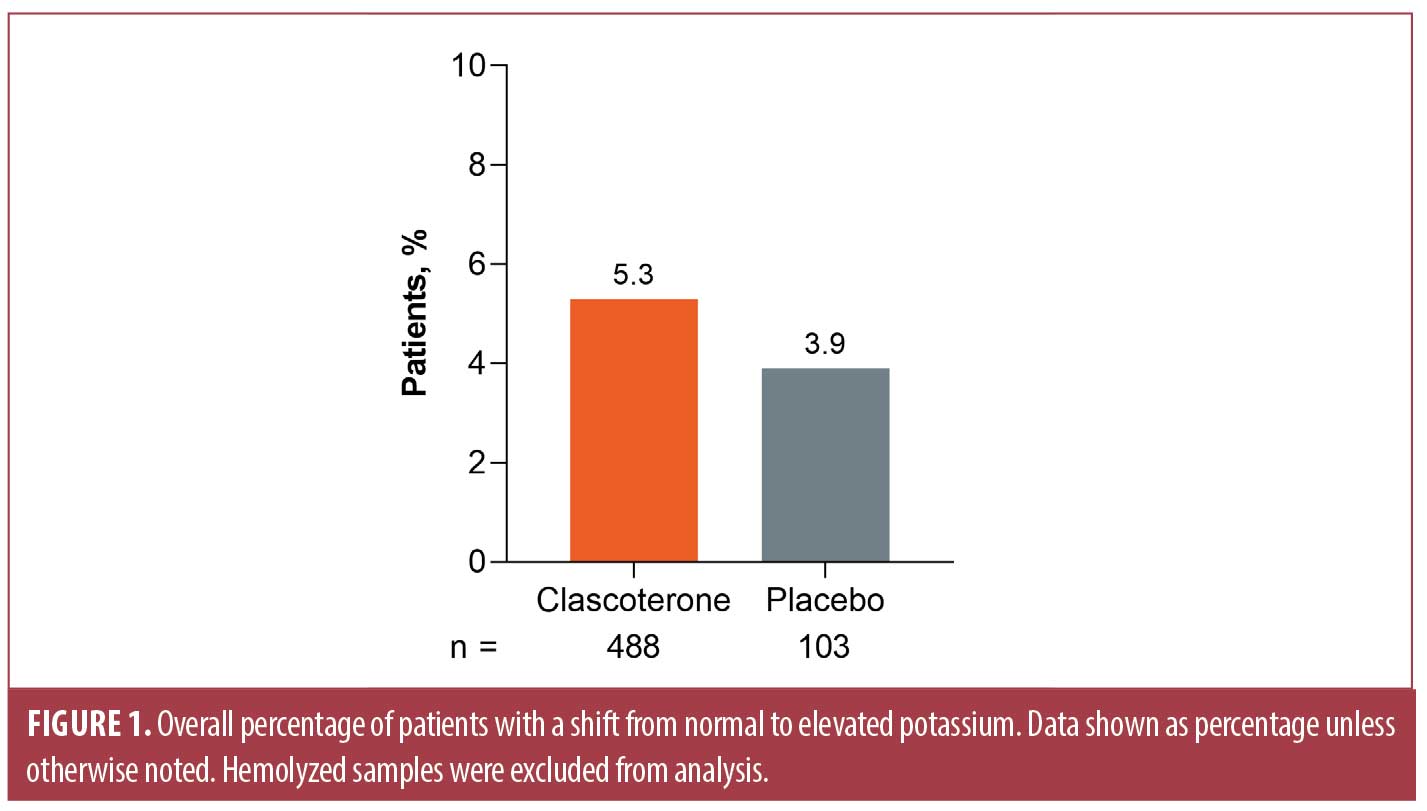

ABSTRACT: Clascoterone cream 1% is an androgen receptor inhibitor approved for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients aged 12 years or older with clinical studies completed in subjects aged nine years or older. Blood potassium levels above the upper limit of normal (i.e., hyperkalemia) were reported in both clascoterone-treated and vehicle-treated patients; reported rates of hyperkalemia were approximately five percent and four percent, respectively. None of the cases of hyperkalemia were reported as adverse events and none led to study discontinuation or adverse clinical sequelae. An exposure-response analysis showed no correlation between plasma concentrations of clascoterone or its metabolite cortexolone and cases of hyperkalemia. Based on the laboratory safety profile of clascoterone demonstrated in the Phase I and Phase II studies, baseline or subsequent laboratory monitoring was not required in the Phase III studies or recommended in the FDA-approved prescribing information. The frequency of shifts to elevated potassium levels was highest in patients younger than 12 years of age treated with clascoterone, for whom clascoterone 1% is not FDA approved. Keywords: Acne, androgen receptor inhibitor, clascoterone, safety, potassium, hyperkalemia

Acne vulgaris (AV) is the most common skin condition affecting adolescents and young adults globally,1,2 with a prevalence of approximately 85 percent in people aged 12 to 25 years.2 The primary hallmarks of AV include excess sebum production and inflammation, processes regulated by both circulating and locally synthesized hormones.1,3 Androgens, including testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), are strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of AV, owing to their regulation of genes that stimulate sebum production and promote acne formation.1,4,5 Clascoterone cream 1% is a novel topical androgen receptor inhibitor that received approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2020,6 with an indication for topical treatment of AV in patients aged 12 years or older.7

Clascoterone has a chemical structure similar to that of other compounds with a steroidal nucleus, including DHT and spironolactone.5 In vitro, clascoterone inhibits the binding of DHT to androgen receptors. The proposed mechanism of action of clascoterone for AV treatment is competition with DHT and other androgens for binding to androgen receptors in the skin, leading to inhibition of the transcription of androgen-responsive genes involved in the pathogenesis of AV.5,8,9 Within the body, clascoterone is rapidly hydrolyzed to cortexolone, a primary inactive metabolite,10,11 thus resulting in limited systemic exposure.11 Results from two identical, vehicle-controlled, Phase III studies12 and a long-term extension safety study13 indicate that clascoterone cream 1% has a favorable safety profile over a study duration of up to 12 months of treatment in patients aged nine years or older with moderate-to-severe AV.

Clascoterone is a first-in-class topical androgen receptor inhibitor for AV treatment in both male and female patients6 that might provide an alternative to systemic antiandrogen medications (i.e., spironolactone and combined oral contraceptives), which are limited for use only in female patients.1,6 While spironolactone generally has a favorable safety profile, laboratory monitoring is recommended with long-term treatment due to the potential risk of systemic adverse effects including hyperkalemia,1,6 which is defined as a plasma potassium level exceeding the upper limit of normal (i.e., >5.0 mmol/L). Although mild hyperkalemia is often asymptomatic, higher potassium levels of 6.5 mmol/L and over can cause life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias, muscle weakness, or cardiac arrest.14 Shifts from normal to elevated potassium levels were observed occasionally in Phase I and Phase II studies of clascoterone treatment;7 however, it is unclear whether clascoterone treatment is associated with a significant risk of hyperkalemia. Here, we describe findings from the FDA multidisciplinary review of the clascoterone clinical development program,15 and provide context for evaluating the clinical relevance of the risk for hyperkalemia in patients treated with topical clascoterone cream 1%.

Methods

Clinical studies. The characteristics of the clinical studies in the clascoterone clinical development program from which laboratory results were evaluated are summarized in Table 1. Laboratory results were pooled from the following studies: three Phase I studies in healthy adults; three pharmacokinetic or maximal use (MUSE) trials in patients with moderate-to-severe AV (one in adults [aged ≥18 years], one in adults and adolescents [aged ≥18 and 12–17 years, respectively], and one in children [aged 9–11 years]); a Phase II vehicle-controlled study in patients aged 12 years or older with moderate-to-severe AV; and a Phase II active-controlled study in adults with facial AV.15 Notably, one study included a clascoterone 7.5% solution formulation not FDA approved for the treatment of AV;16 all other studies evaluated clascoterone cream ≤1%.15

In the MUSE studies, patients applied clascoterone cream diffusely to the entire face, shoulders, upper chest, and upper back. Adult and adolescent patients applied 6g of clascoterone cream twice daily, adolescents aged 18 years or younger with body surface area 1.6m2 or less applied 4g twice daily, and children aged 9 to 11 years applied 2g twice daily.11,15 The mean daily total amount of clascoterone cream 1% applied in MUSE trials in adult, adolescent, and pediatric patients (Table 2) was approximately 5.7-fold, 4.9-fold, and 2.2-fold higher, respectively, than the approximately 1g twice-daily dose applied in the Phase III pivotal studies,15 which is the recommended dose indicated in the FDA-approved product labeling.7

Safety assessments. During the first and final visits, blood samples were collected from each patient for clinical laboratory evaluations;11,16–18 blood samples were also collected following the first and last topical clascoterone applications for analysis of plasma concentrations of clascoterone and cortexolone using high-performance liquid chromatography.11 To determine the safety profile of clascoterone cream, clinical laboratory results were pooled from all applicable studies for evaluation of abnormal changes in potassium levels. Additional pooled safety data evaluated in the review included treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE), serious adverse events (SAE), and adverse events (AEs) leading to discontinuation. A TEAE was defined as an AE with onset on or following the first application of the study drug. All reported terms for AEs were recorded using the most recent version of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, version 21.0).15

Statistical analysis. As described in the review,15 shift tables of chemistry results were generated to summarize the normal and abnormal changes from baseline to the worst postbaseline results. The percentage of patients who shifted from low, normal, or missing potassium levels to elevated potassium levels was calculated among patients with a baseline and at least 1 postbaseline value across all studies. The baseline value of each variable was defined as the value recorded at the last visit on or prior to the first application of the study drug. Least squares (LS) mean and difference in percentage change from baseline in potassium levels were calculated based on an analysis of covariance including treatment, baseline value, and age. An exposure-response analysis was conducted to explore the possibility of correlation between systemic clascoterone exposure under MUSE conditions and occurrence of hyperkalemia. Hemolyzed samples were excluded from analysis.

Results

Laboratory findings in patients treated with topical clascoterone. Shifts in potassium levels were evaluated in 598 patients (n=495 clascoterone, n=103 vehicle) across all studies. After exclusion of seven hemolyzed samples from patients treated with clascoterone, 26 of 488 (5.3%) clascoterone-treated patients and 4 of 103 (3.9%) vehicle-treated patients shifted from low, normal, or missing potassium levels to elevated potassium levels above the upper limit of the normal range (Figure 1). The LS mean maximum percentage change from baseline in patients receiving clascoterone was 0.10 percent, compared with 0.06 percent in patients receiving vehicle (difference, 0.03%; 95% confidence interval, −2.20% to 2.27%; Table 3).

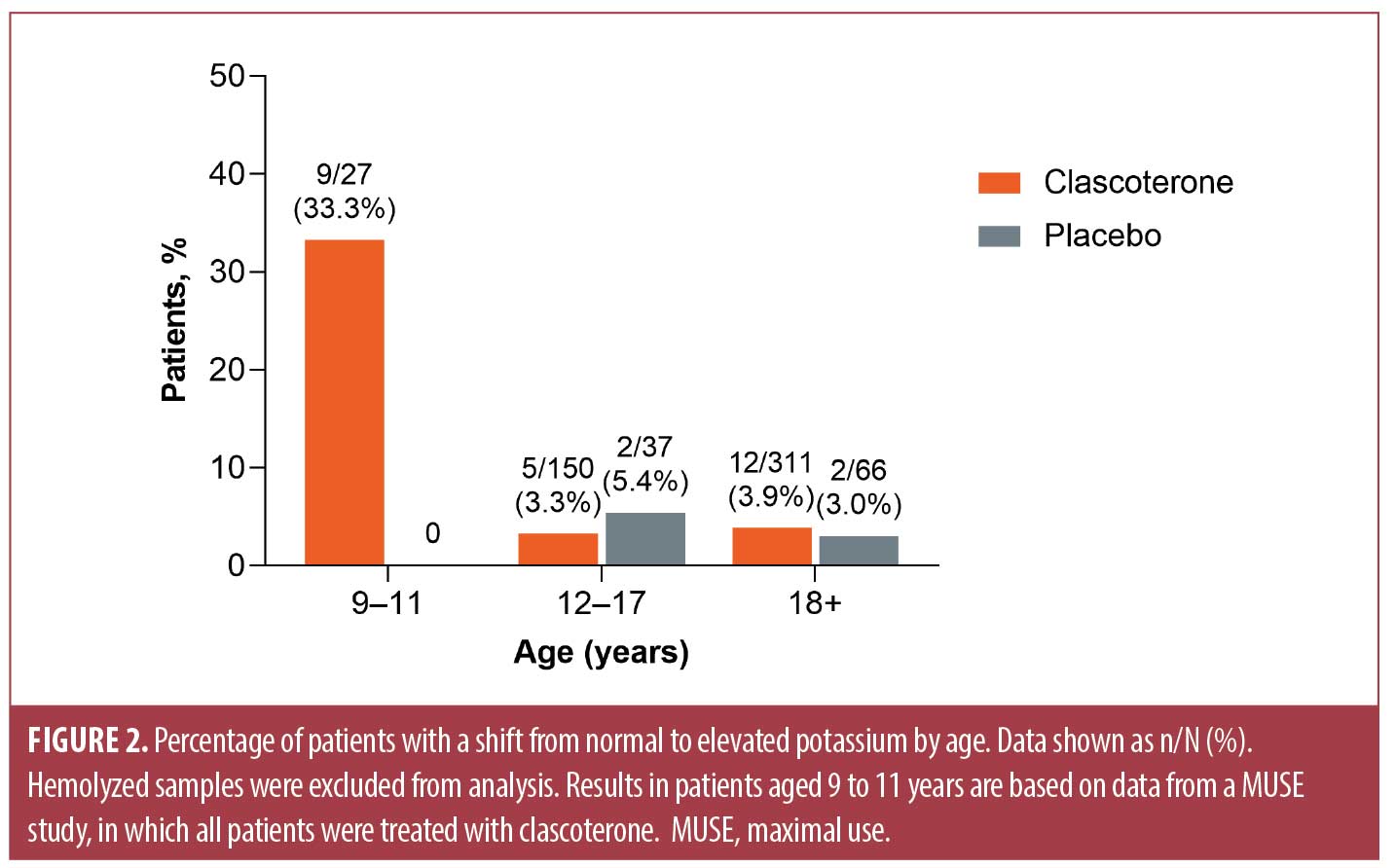

When results were stratified by age, the highest percentage of shifts to elevated potassium levels was noted in patients aged 9 to 11 years (9/27 patients; 33%) based on data from a MUSE study in pediatric patients with AV (Figure 2). Shifts to elevated potassium levels were observed in 3.3 percent (5/150) and 3.9 percent (12/311) of clascoterone-treated patients aged 12 to 17 years and 18 years or older, respectively; corresponding values in vehicle-treated patients were 5.4 percent (2/37) and 3.0 percent (2/66), respectively.

Exposure-response analysis. An exposure-response analysis was conducted to explore the possibility of correlation between systemic clascoterone exposure under MUSE conditions and occurrence of hyperkalemia. In patients aged 9 to 11 years who shifted to elevated potassium levels, plasma concentrations of both clascoterone and the primary metabolite cortexolone were generally low (Table 4), and there was no clear correlation between plasma concentrations of clascoterone or cortexolone and cases of hyperkalemia (data not shown).

Laboratory-related adverse events in clascoterone clinical studies. Overall, five patients treated with clascoterone experienced eight laboratory-related AEs during the studies in which they were evaluated (Table 5), none of which were SAEs. The majority of the laboratory-related AEs reported were mild in severity, and none were considered to be related to the study drug. In a Phase II dose-escalating study, one patient treated twice daily with clascoterone cream 1% had an AE of elevated liver function tests, which resulted in discontinuation of the study drug; the patient completed the study. Notably, none of the laboratory findings of hyperkalemia were reported as AEs, and there were no laboratory-related AEs leading to study discontinuation in any of the trials. No patient deaths were reported.

Discussion

Hyperkalemia was observed as a laboratory finding in approximately five percent of clascoterone-treated patients and four percent of vehicle-treated patients in the clascoterone clinical development program. Overall, no significant differences in maximum percentage change from baseline in potassium levels were observed between clascoterone- and vehicle-treated patients. Patients younger than 12 years treated with clascoterone under MUSE conditions had the highest frequency of hyperkalemia. However, in the pediatric patients who experienced shifts to elevated potassium levels, the occurrence of hyperkalemia did not appear to be associated with increased plasma concentrations of clascoterone, and no exposure-response relationship was found.

The frequency of laboratory-related AEs was low across the clascoterone trials. Most reported laboratory-related AEs were mild in severity, and none were considered to be related to the study treatment. Although shifts to elevated potassium levels were observed as an occasional laboratory finding, none were reported as AEs or resulted in study discontinuation. A primary clinical concern with elevated potassium levels is the risk for cardiac arrhythmias or cardiac arrest.14 However, in an electrocardiogram safety study, treatment with a clascoterone 7.5% solution was not associated with any clinically significant cardiac abnormalities.16 Based on the laboratory safety profile of clascoterone demonstrated in the Phase I and Phase II studies, baseline or subsequent laboratory monitoring was not required in the Phase III studies or recommended in the FDA-approved prescribing information.

Conclusion

Shifts to elevated potassium levels were observed as an occasional laboratory finding in both clascoterone- and vehicle-treated patients, but no exposure-response relationship was established between plasma concentrations of clascoterone or cortexolone and cases of hyperkalemia. The frequency of shifts to elevated potassium levels was highest in patients treated with clascoterone who were younger than 12 years of age, for whom clascoterone 1% is not FDA approved.

References

- Elsaie ML. Hormonal treatment of acne vulgaris: an update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:241–248.

- Lynn DD, Umari T, Dunnick CA, et al. The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2016;7:13–25.

- Moradi Tuchayi S, Makrantonaki E, Ganceviciene R, et al. Acne vulgaris. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15029.

- Dart DA. Androgens have forgotten and emerging roles outside of their reproductive functions, with implications for diseases and disorders. J Endocr Disord. 2014;1(1):1005.

- Kircik LH. Game changer in acne treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(3):28.

- Piszczatoski CR, Powell J. Topical clascoterone: The first novel agent for acne vulgaris in 40 years. Clin Ther. 2021;43(10):1638–1644.

- WINLEVI® (clascoterone cream 1%). Prescribing Information. Cranbury NJ: Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.; Sep 2021.

- Rosette C, Agan FJ, Mazzetti A, et al. Cortexolone 17alpha-propionate (clascoterone) is a novel androgen receptor antagonist that inhibits production of lipids and inflammatory cytokines from sebocytes in vitro. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(5):412–418.

- Rosette C, Rosette N, Mazzetti A, et al. Cortexolone 17alpha-propionate (clascoterone) is an androgen receptor antagonist in dermal papilla cells in vitro. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(2):197–201.

- Ferraboschi P, Legnani L, Celasco G, et al. A full conformational characterization of antiandrogen cortexolone-17α-propionate and related compounds through theoretical calculations and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. MedChemComm. 2014;5(7):904–914.

- Mazzetti A, Moro L, Gerloni M, et al. Pharmacokinetic profile, safety, and tolerability of clascoterone (cortexolone 17-alpha propionate, CB-03-01) topical cream, 1% in subjects with acne vulgaris: An open-label phase 2a study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(6):563.

- Hebert A, Thiboutot D, Stein Gold L, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical clascoterone cream, 1%, for treatment in patients with facial acne: Two phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(6):621–630.

- Eichenfield L, Hebert A, Gold LS, et al. Open-label, long-term extension study to evaluate the safety of clascoterone (CB-03-01) cream, 1% twice daily, in patients with acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):477–485.

- Abuelo JG. Treatment of severe hyperkalemia: Confronting 4 fallacies. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(1):47–55.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Clascoterone cream 1% NDA 213433 multidisciplinary review and evaluation, August 19, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/media/142578/download.

- Taubel J, Mazzetti A, Ferber G, et al. A phase 1 study to investigate the effects of cortexolone 17alpha-propionate, also known as clascoterone, on the QT interval using the meal effect to demonstrate ECG assay sensitivity. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2021;10(6):572–581.

- Mazzetti A, Moro L, Gerloni M, et al. A phase 2b, randomized, double-blind vehicle controlled, dose escalation study evaluating clascoterone 0.1%, 0.5%, and 1% topical cream in subjects with facial acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(6):570.

- Trifu V, Tiplica GS, Naumescu E, et al. Cortexolone 17alpha-propionate 1% cream, a new potent antiandrogen for topical treatment of acne vulgaris. A pilot randomized, double-blind comparative study vs. placebo and tretinoin 0.05% cream. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(1):177–183.