by Laura Paul Fite, MD, and Philip R. Cohen, MD

by Laura Paul Fite, MD, and Philip R. Cohen, MD

Dr. Fite is with Shenandoah Dermatology in Staunton, Virginia. Dr. Cohen is with the Department of Dermatology at University of California San Diego in La Jolla, California.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Keywords: Acanthosis nigricans, azithromycin, Carteaud, confluent, Gougerot, ovarian, papillomatosis, polycystic, reticulate, reticulated, syndrome, treatment

Abstract: Polycystic ovarian syndrome is a common endocrine disorder with a variety of dermatologic manifestations among young women. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare dermatosis of unknown etiology that is seldom reported in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome. We describe the case of a young woman with obesity, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, and concurrent acanthosis nigricans. Her history, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation led to the diagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome. The proposed etiologies and the various of treatment options for confluent and reticulated papillomatosis are discussed. In our case, the patient had a dramatic response to treatment with azithromycin. The etiology of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis remains to be established. Additionally, the mechanism behind the success of treatment with antibiotics is unclear; however, in this patient, azithromycin was a safe and effective option for the treatment of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10(9):30–35

Introduction

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder among women of reproductive age. A general diagnosis is made using the Rotterdam consensus criteria, which require two of the following three features: 1) oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, 2) clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism, and 3) polycystic ovaries demonstrated by ultrasound.[1,2] These criteria also require the exclusion of other etiologies. Cutaneous stigmata seen in patients with PCOS include acanthosis nigricans, acne, androgenic alopecia, hirsutism, and seborrhea; rarely, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP) has been described in patients with PCOS or insulin resistance.[3–5] We report a woman with PCOS-associated CARP, and we discuss the successful management of her dermatosis with azithromycin.

Case Report

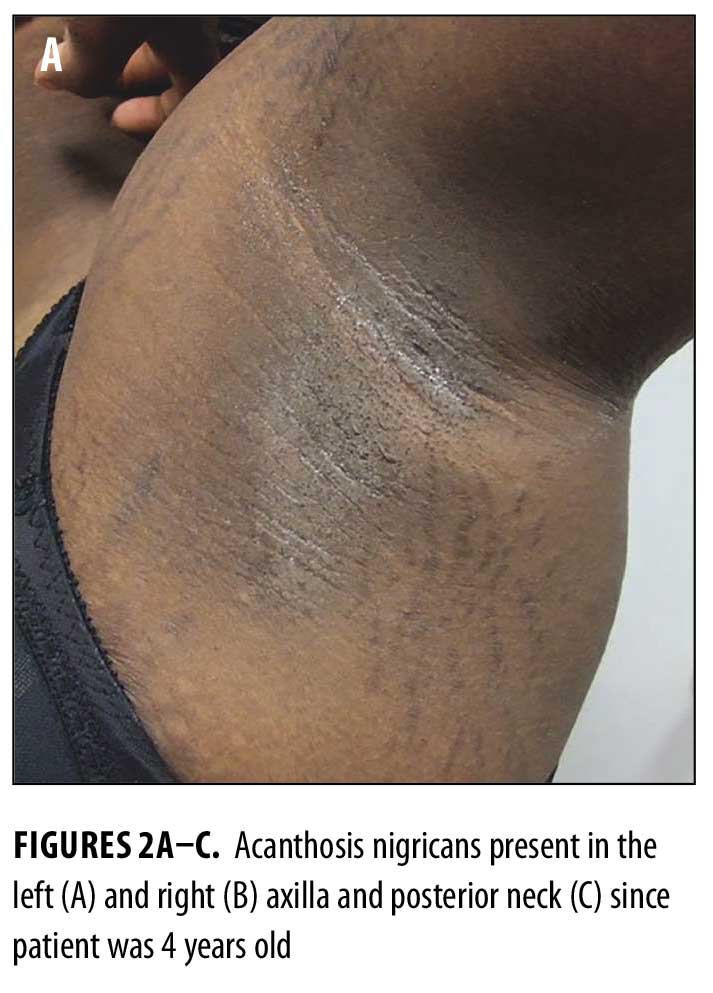

A 19-year-old African American woman presented with a chief complaint of skin discoloration on her chest, face, and back. She reported the skin changes began as a small spot on her back when she was 13 years old. Her medical history was significant for onset of acanthosis nigricans on her neck and axillae at age four years, as well as obesity, hirsutism, irregular menstrual cycles, and recent onset of photosensitivity.

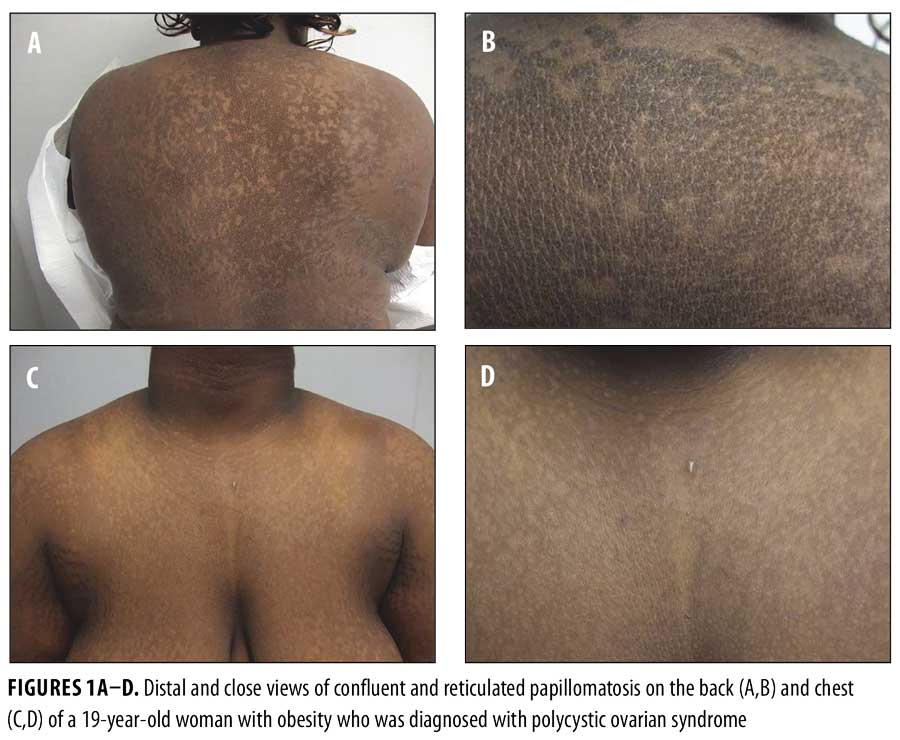

Physical examination revealed reticulated, hyperpigmented patches and lichenified, hyperpigmented plaques on her neck, chest, back, and abdomen (Figures 1A–D). Thickened, velvety plaques typical of acanthosis nigricans were also present at the nape of her neck and axillae (Figures 2A–C).

Potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings from her back and chest were negative for hyphae. A 3mm punch biopsy was taken from the lesion on her back. A second 3mm punch was also taken from normal skin on her back for comparison.

Laboratory tests for evaluation of polycystic ovarian syndrome were sent, including luteinizing hormone (LH)—18.5MIU/mL and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)—4.7MIU/mL for a ratio of more than 3.5:1 (n=<2:1), prolactin—13ng/mL (n=2-27), estradiol—126pg/mL (n=30–400), 17-hydroxyprogesterone—94ng/dL (n<207), dihydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS)—108µg/dL (n=35–430), total serum testosterone—76ng/dL (n=14–76), 24-hour urine free cortisol—15.6µg/day (n<45), insulin level—16 (n=6–27), and fasting blood sugar—85mg/dL. Laboratory evaluation for photosensitivity included erythrocyte sedimentation rate (10mm/hr [n=0–20]) and antinuclear antibody (positive with titer of 1:160), and the following antibodies were all found to be negative: anti-double stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), anti-Smith, Sjogren’s SS-A and SS-B, anti-ribonucleoprotein (RNP), and anti-histone.

Laboratory studies and clinical findings confirmed the diagnosis of PCOS. Other potential causes of hyperandrogenism, specifically late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s syndrome, and androgen-producing tumors, were ruled out through laboratory results. Pelvic ultrasound was not performed. Evaluation for her photosensitivity did not reveal a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Microscopic examination of the lesional biopsy revealed prominent papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and yeast forms present in the stratum corneum consistent with a diagnosis of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP); these changes were absent from the biopsy specimen of normal appearing skin.

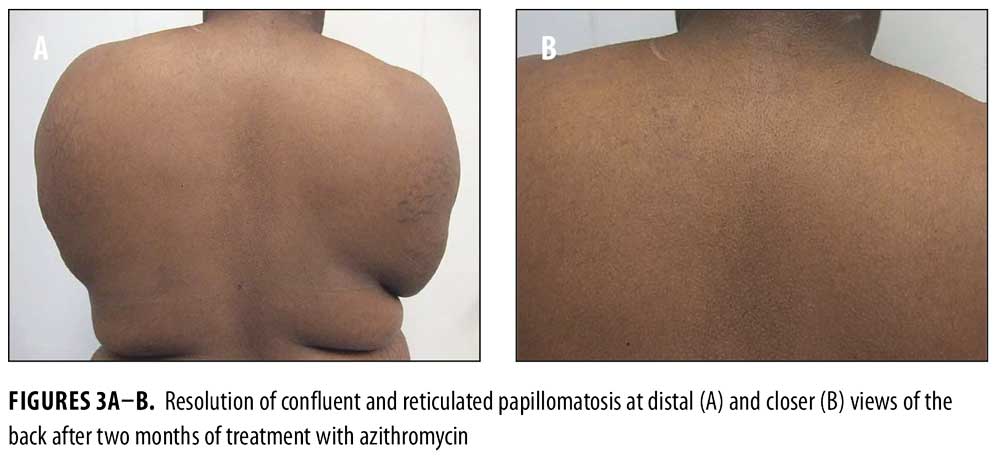

Topical tretinoin 0.025% cream was prescribed daily for the sites of acanthosis nigricans on her neck and axillae. Treatment of her CARP was initiated with azithromycin 500mg three times weekly for two months. For her photosensitivity, sun avoidance and sunscreen were recommended. Metformin, initially at 500mg daily and progressively increased to 2g daily, was given for her newly diagnosed PCOS. There was improvement of her acanthosis nigricans. The patient also had complete resolution of her CARP lesions after two months of azithromycin, and no recurrence after the medication was tapered and discontinued (Figures 3A–3B).

Discussion

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis was first described in 1927 by Gougerot and Carteaud.6 It is characterized by hyperkeratotic and verrucous papules that coalesce into plaques centrally and form a reticular pattern at the periphery. Initially, the lesion may begin with only a few papules that then grow and increase in numbers. They range from erythematous to dull brown in color. The dermatosis is most commonly present on the upper body—specifically on the chest, abdomen, and back, although other areas have been reported.[7–9]

CARP is known to occur worldwide, most commonly in adolescents and young adults, and in general is thought to have no sex preference. 10 However, Lee et al11 reviewed 41 cases reported in the literature from 1978 to 1992. They found an average age of onset to be 19.4 years of age with a predominance of men. Another study by Davis et al12 reviewed 39 patients who presented to their clinic with CARP between 1972 to 2003 and found the mean age of onset was 15 years and an even ratio of men to women. In this case series, researchers also proposed criteria for diagnosis of CARP to include papillomatous, reticulated brown macules and patches, involvement of the upper trunk and neck, negative result for fungal staining, no response to antifungal treatment, and positive response to minocycline.[12]

The histologic features of CARP include hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis with mild-to-moderate increase in pigmentation.[3,10] Sparse perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and dilation of superficial vessels may be noted in the dermis.[10] These changes resemble some of the histologic features of acanthosis nigricans; however, they are less pronounced in comparison. Pityrosporum yeast forms may or may not be present.[10]

The etiology for CARP is unclear although many hypotheses have been suggested. The strongest support is for a disorder of keratinization because of the histologic features and response to treatment with retinioids and vitamin D derivatives.[10,11,13–21] However, this theory does not explain the excellent response of CARP to treatment with antibiotics, which are not known to directly affect keratinization.

Recent reports have attempted to link bacteria to the etiology of CARP. Natarajan et al[22] isolated a newly discovered Actinomycete called Dietzia from the skin scrapings of a patient with biopsy-proven CARP. The patient responded to treatment with a six-week course of minocycline. However, five months later, the patient had a minor recurrence of his CARP, and the investigators were not able to isolate the bacteria from his recurrent lesions.[22] It was also previously suggested that the role of bacteria may be related to an alteration of sebum by host bacteria or perhaps an abnormal response to the bacteria, because CARP frequently occurs in adolescents and has a predilection for seborrheic areas.[23]

There have been reports of successful treatment of CARP with topical antifungals; however, this could be due to the patients actually having isolated or superimposed tinea versicolor. As mentioned previously, yeast forms may be present in the biopsy specimens of CARP lesions. However, in the proposed criteria by Davis et al,[12] unsuccessful response to antifungals is listed as criterion for diagnosis of CARP. Also, a recently published report observed four different cases of CARP that clinically presented as hypopigmented lesions in dark-skinned individuals in whom CARP clinically presented as hypopigmented lesions.[24] All of the cases were biopsy-proven CARP and responded to minocycline. In addition, it is also prudent to consider the possibility of CARP in patients with suspected tinea versicolor who do not respond to antifungal treatment.

Endocrine abnormalities have been observed in patients with CARP. These include impaired glucose tolerance, hyperinsulinemia, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, and PCOS.[3–5,25] The presence of acanthosis nigricans and CARP has also been reported previously. Patients with either PCOS or insulin resistance associated with CARP are summarized in Table 1.[3–5] It is reasonable to postulate that CARP might actually be more common in individuals with PCOS and/or insulin resistance than the small number of patients we have identified. Both acanthosis nigricans and CARP are considered disorders of keratinization and could be mistaken for each other as neither are symptomatic and generally only brought to attention for cosmetic reasons. Indeed it had once been proposed that perhaps acanthosis nigricans and CARP were part of the same disease spectrum or even the same entity.[3,5,10] However, they have been determined to be distinct conditions with distinct histopathology. Others have suggested there are common predisposing factors between acanthosis nigricans and CARP in patients with obesity.[5]

In one report, investigators suggest that in the setting of insulin resistance and obesity, CARP and acanthosis nigricans might not be distinct disorders, but instead an expected clinical feature.[4] This hypothesis was taken further when other researchers proposed that the excessive levels of insulin result in inappropriate activation of distinct cellular receptors, which promote epidermal proliferation and papillomatosis that result in acanthosis nigricans and, perhaps, CARP as well.[3,26] Therefore, a common pathogenic pathway in patients with insulin resistance might lead to the two distinct skin conditions.[3]

If CARP is indeed associated with insulin resistance, then medications that increase insulin sensitivity, such as metformin, might be helpful in the approach to treatment. In our report, the patient was simultaneously started on metformin and azithromycin. It is, therefore, possible that she responded to the metformin rather than the azithromycin. However, there is no way to determine if that was the case for this patient. Further studies in the future might help to elucidate the role of insulin resistance in the development of CARP and also guide the approach to treatment.

The ideal management of CARP remains to be established. Some of the therapies have been successful in only a few individuals, whereas others have been proven to be more widely beneficial. These treatment options are summarized in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Our patient had a history of photosensitivity. Since minocycline can potentially be associated with phototoxic reactions, her CARP was treated with azithromycin. She had a dramatic response. Similar efficacious responses of CARP to azithromycin7,[27–32] have been described in reports of individual patients; however, this antibiotic is not as widely used as minocycline.[12,23,28,33] Azithromycin should be considered a viable option for treatment in patients with CARP.

There are less adverse effects associated with azithromycin compared with minocycline. Also, since azithromycin is now available in a generic formulation, it is less expensive than it was in the past.

The benefit of antibiotics in the management of CARP might lie in their antibacterial properties but it is also likely that their anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects are responsible. The tetracyclines in particular are well known for their effects on acne even when given in lower doses than is needed for antibacterial effects.[36] In-vitro studies have also shown that macrolides modulate the production of inflammatory cytokines and therefore also have immunosuppressive effects.[37] In contrast, some investigators argue that these properties of antibiotics might not play a significant role in the management of CARP, as only mild inflammation is seen on histologic exam of CARP specimens.[28]

Other miscellaneous agents have been shown to be successful in the management of CARP, although their mechanisms of action do not obviously result in effects that would alter the histopathologic findings observed in CARP. For example, in one report, a patient with a histologic diagnosis of CARP was found to have no signs of fungal species present, as evidenced by a negative KOH stain, negative Wood’s light examination, and absence of fungal elements in the biopsy sections stained with periodic acid-Schiff’s reagent.[38] The patient’s CARP was treated with topical selenium sulfide lotion nightly, and after three weeks his CARP was 90-percent improved, with complete clearance occurring after five weeks. His response to the therapy was unexpected, but the authors suggested that this therapy should be given a trial before moving on to systemic agents, which have more potential adverse side effects.[38]

Conclusion

CARP is a rare condition of unknown etiology. It is possible that the pathogenic mechanisms differ depending on the patient. This is evidenced by the development of CARP in not only patients with obesity, insulin resistance, and/or PCOS, but also in healthy patients. Individual patients may respond to different treatment modalities—an option might be successful in one patient but not in another. Further investigations might be able to define the best treatment. In our experience, azithromycin was a safe and effective treatment that resulted in complete clearance without recurrence.

References

- Lowenstein EJ. Diagnosis and management of the dermatologic manifestations of the polycystic ovary syndrome. Dermatol Ther. 2006; 19: 210–223.

- Broekmans FJ, Fauser Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovarian syndrome. Endocrine. 2006; 30: 3–11.

- Cannavo SP, Guarneri C, Borgia F, Guarneri B. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis and acanthosis nigricans in an obese girl: two distinct pathologies with a common pathogenetic pathway or a unique entity dependent on insulin resistance? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006; 20: 478–480.

- Ozdemir S, Ozdemir M, Toy H. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis associated with polycystic ovary syndrome treated with combined contraceptive containing drospirenone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008; 23: 358–359.

- Hirokawa M, Matsumoto M, Iizuka H. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a case with concurrent acanthosis nigricans associated with obesity and insulin resistance. Dermatology. 1994; 188: 148–151.

- Gougerot H, Carteaud A. Papillomatose pigmentée innominée. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1927; 34: 719.

- Atasoy M, Alaiagaoglu C, Erdem T. A case of early onset confluent and reticulated papillomatosis with an unusual localization. J Dermatol. 2006; 33: 273–277.

- Kim BS, Lim HJ, Kim HY et al. Case of minocycline-effective confluent and reticulated papillomatosis with unusual location on forehead. J Dermatol. 2009; 36: 251–253.

- Lee D, Cho KJ, Hong SK et al. Two cases of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis with an unusual location. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009; 89: 84–85.

- Scheinfeld N. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006; 7: 305–313.

- Lee MP, Stiller MJ, McClain SA, et al. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: response to high-dose oral isotretinoin therapy and reassessment of epidemiologic data. J Amer Acad Dermatol. 1994; 31: 327–331.

- Davis MDP, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. a study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006; 154: 287–293.

- Bowman PH, Davis LS. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: response to tazarotene. J Amer Acad Dermatol. 2003; 48: S80–S81.

- Bruynzeel-Koomen CA, de Wit RF. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis successfully treated with the aromatic etretinate. Arch Dermatol. 1984; 120: 1236–1237.

- Hodge JA, Ray MC. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: response to isotretinoin. J Amer Acad Dermatol. 1991; 24: 654.

- Solomon BA, Laude TA. Two patients with confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: response to oral isotretinoin and 10% lactic acid lotion. J Amer Acad Dermatol. 1996; 35: 645–646.

- Baalbaki SA, Malak JA, Al-Khars MA, Aramco-Dhahran S. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: treatment with etretinate. Arch Dermatol. 1993; 129: 961–963.

- Vassileva S, Pramatarov K, Popova L. Ultraviolet light-induced confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989; 21: 413–414.

- Ginarte M, Fabeiro JM, Toribio J. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud) successfully treated with tacalcitol. J Dermatol Treat. 2002; 13: 27–30.

- Carozzo AM, Gatti S, Ferranti G et al. Calcipotriol treatment of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000; 14: 131–133.

- Gulec AT, Seckin D. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Br J Dermatol .1999; 141: 1150–1151.

- Natarajan S, Milne D, Jones AL, et al. Dietzia strain X: a newly described Actinomycete isolated from confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. Br J Dermatol. 2005; 153: 825–827.

- Montemarano AD, Hengge M, Sau P, Welch M. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: Response to minocycline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996; 34: 253–256.

- Hudacek KD, Haque MS, Hochberg AL, et al. An unusual variant of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis masquerading as tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2012; 148: 505–508.

- Kesten BM, James HD. Pseudoatrophoderma colli, acanthosis nigricans, and confluent and reticular papillomatosis. AMA Arch Derm. 1957; 75: 525–542.

- Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002; 147: 1096–1101.

- Gruber F, Zamolo G, Saftic M, et al. Treatment of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis with azithromycin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998; 23: 191.

- Jang HS, Oh CK, Cha JH, et al. Six cases of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis alleviated by various antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001; 44: 652–655.

- Atasoy M, Ozdemir S, Akta A, et al. Treatment of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis with azithromycin. J Dermatol. 2004; 31: 682–686.

- Atasoy M, Aliagoaglu C. Is confluent and reticulated papillomatosis without papillomatosis early or late stage of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis? J Cutan Pathol. 2006; 33: 52–54.

- Chaudhry SI, Lai Cheong JE, O’Donoghue NB. A rash on the back. clinicopathological case. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006; 31: 727–728.

- Raja Babu KK, Snehal S, Sudha Vani D. Confluent and reticulate papillomatosis: successful treatment with azithromycin. Br J Dermatol. 2000; 142: 1252–1253.

- Chang SN, Kim SC, Lee SH, Lee WS. Minocycline treatment for confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. Cutis. 1996; 57: 454–457.

- Ito S, Hatamochi A, Yamazaki S. A case of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis that successfully responded to roxithromycin. J Dermatol. 2006; 1: 71–72.

- Angeli-Besson C, Koeppel MC, Jacquet P, et al. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud) treated with tetracyclines. Int J Dermatol. 1995; 34: 567–569.

- Humbert P, Treffel P, Chapuis JF, et al. The tetracyclines in dermatology. J Am Acad. Dermatol 1991; 25: 691–697.

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Macrolides beyond the conventional antimicrobials: a class of potent immunomodulators. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008; 31: 12–20.

- Friedman SJ, Albert HL. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud: treatment with selenium sulfide lotion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986; 14: 280–282.

- Hamaguchi T, Nagase M, Higuchi R, Takiuchi I. A case of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis responsive to ketoconazole cream. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2002; 43: 95–98.