J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(4):21–25.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(4):21–25.

by Ankita Tuknayat, MBBS, MD; Mala Bhalla, MD; Kanika Dogar, MBBS;

Gurvinder Pal Thami, MD; and Jasleen Kaur Sandhu, MD

All authors are with the Department of Dermatology at the Government Medical College and Hospital in Chandigar, India.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts on interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. The COVID-19 pandemic has shifted healthcare from physical in-person patient visits to teleconsultations in order to curtail the spread of this virus. Dermatology, being a visual science, lends itself amenably to teleconsultation.

Objective. This study was performed to assess the basic dermatological diseases which are more easily diagnosable and managed through teleconsultation, distinguishing them from diseases for which a face-to-face consultation may be a better option and to delineate the factors affecting the image quality which is the cornerstone of a teledermatology consultation.

Methods. A retrospective observational study was conducted over a three-month period during the pandemic. Store and forward, video conferencing, and hybrid consultations were included. Two dermatologists of different clinical experience independently assessed the clinical photographs of the patients and gave each photograph an objective score (Physician Quality Rating Scale) and a diagnosis. The diagnostic concordance between the two dermatologists as well as the correlation of this score with the certainty of diagnosis was calculated.

Results. A total of 651 patients completed the study. Mean PQRS score of Dermatologist 1 was 6.22 while the mean score of Dermatologist 2 was 6.24. Patients in whom both the dermatologists were absolutely certain about their diagnosis had a higher PQRS score and interestingly had a higher education level than the rest. There was 97.7 percent diagnostic concordance between the two dermatologists. Infections, acne, follicular disorders, pigmentary disorders, tumors, and STDs had the largest proportion of cases wherein both the dermatologists were in total agreement with each other. Conclusion: Teledermatology might be best for the care of patients with characteristic clinical presentation or for follow-up of already diagnosed patients. It can be used in the post-COVID era to triage patients requiring emergency care and reduce patient wait times.

Keywords: Teledermatology, telemedicine, COVID-19

Telemedicine (TM) is described as the use of electronic information and communication technology to fulfill healthcare needs of participants separated by a physical distance.1-2 It was initially used to make remote areas accessible to healthcare facilities and to enable fast and effective delivery of healthcare. Though it has been in limelight during the pandemic, it was being used earlier in certain fields of medicine like radiology, pathology, psychiatry, surgery, dermatology, etc. to enable remote consultations.3-4

In the pre-COVID era, the use of TM was limited to increase accessibility to expert opinions and to reduce the patients’ travel cost, but in the present pandemic scenario it has become almost a necessity.5 Since the beginning of 2020, there have been strict national guidelines to maintain social distancing and to avoid unnecessary hospital visits in order to protect people from this potentially life threatening virus.6 The vital role of TM came to the fore in such extreme circumstances to help in the delivery of healthcare to all.7,8 It is specifically relevant in dermatology which is predominantly a visual science with inspection being the key factor in establishing the diagnosis of dermatoses with visible pathognomic characteristics. It is important to study the type of patients who present through this route and the accuracy of the diagnosis made by the dermatologist to see whether this practice can be continued in the post COVID era as a triage to reduce the patient load in the overburdened OPDs. Store-and-forward technique (SAFT) is the most commonly used teledermatology tool. Its diagnostic accuracy is said to be close to 80 percent.9 The accuracy of the diagnosis made by the dermatologist depends predominantly on the quality of the image submitted by the patient which further depends on a number of factors like the education of the patient, the quality of the device through which the photographs are being sent, etc.10 Though telemedicine has been advocated, there is still a lot of gray area regarding its legal and financial aspects. Another point to note is that the ease of using teledermatology may vary from person to person based on their non-familiarity with the process of using it. While some patients may find it easier to use maintaining their anonymity, others may find it embarrassing to send the photos of some specific regions of their body.

There have been very few studies on the clinical aspects of the patients presenting to the teledermatology OPD as well as factors which aid the doctor to make a concrete diagnosis.11-13 This study was done keeping in mind the ongoing exponential increase in teleconsultations so as to assess the basic dermatological diseases which are more easily diagnosable and managed through this route segregating them from diseases for which a face to face consultation may be a better option. Also an effort was made to delineate the factors affecting the image quality which is the cornerstone of a teledermatology consultation.

Methods

This is a retrospective observational study carried out in a tertiary care hospital from April 2020 to July 2020. All the patients who attended teledermatology Out Patient Department (OPD) within this period were included in the study. Patient population comprised of darker skin types (Fitzpatrick Skin Type 4 and 5) where the incidence of melanoma and actinic keratosis is not that high. The study was approved by institutional review board. The study included store and forward, real time as well hybrid consultations through mobile teleconsultation (digital camera with an average 640×480 pixels image resolution). The images were stored in JPEG (Joint Photographers Expert Group) format using the internet.

Inclusion criteria. Patients of all ages who were able to send a photograph and a valid identification proof through teledermatology were included.

Exclusion criteria. Patients who did not give the required history were not inlcuded.

A detailed proforma including the demographic details of the patients, clinical signs and symptoms, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, whether diagnosis could be made by image sent by patient alone, whether supplementary images were required and clarity of the image sent by the patient was filled by two dermatologists separately. Both dermatologists completed a pre-study test of images of twenty common dermatological conditions. The diagnoses were classified into ten major groups which included infections, acne and related follicular disorders, tumors, sexually transmitted diseases, eczematous disorders, vasculitis and connective tissue disorders, immune-bullous disorders, papulo-squamous disorders, hair and nail disorders, and pigmentary disorders. All cases were categorized into three according to the certainty of diagnosis: absolutely certain (when there was only one diagnosis), moderately certain (when not more than two differentials were considered), and not certain (when three or more than three differentials were considered). Two dermatologists of different clinical experience (≤5 years designated as Dermatologist 1 and >5 years designated as Dermatologist 2) assessed the photographs separately and gave the photographs a PQRS (Photograph Quality Rating Scale) score and a diagnosis.13 It included five parameters: Color, Perspective, Clarity, Darkness and Brightness. Each of these was given a score of 0 to 2 with a total score being 10. Both of the dermatologists gave the score separately to each image and the average of the score was taken into account. The cases where both the dermatologists agreed on a single diagnosis was considered accurate diagnosis. All of these patients were followed up for at least two weeks to assess therapeutic response to the treatment given as per the diagnosis which was considered as a pointer towards the accuracy of the diagnosis as face to face consultation could not be done for all patients because of strict COVID appropriate guidelines and limited operability of all hospitals during that time. For the purpose of the study, patients where there was lack of consensus in the diagnosis between the two dermatologists were called for an in-person visit. Patients with severe cutaneous disease directly presented to the emergency as it was operational during the pandemic.

Information on different components of PQRS score was printed by using absolute number with percentages, then average scores were compared in different subgroups of patients. Based on the characteristics of patients, aggregated PQRS score was compared in different subgroups of diagnostic categories by using Mann-Whitney test and analysis of variants ANOVA in case of more than two categories. The significance of association between PQRS score and diagnosis was tested by using X2 Test of significance. Interclass correlation coefficient was calculated between two different raters assessing the PQRS score for making diagnosis. The significance of observed coefficient was tested in association with PQRS score. Cohen’s kappa was used for interrater agreement for categorical variables. Weighted kappa was used in case of ordinal variables. Data analysis was carried out by using SPSS- 26.0 Software.

Results

A total of 651 patients completed the study which included 369 (56.7%) males and 282 (43.3%) females (Table 1). The mean age was 30.51 years. In around 60 percent of the cases, both the dermatologists were absolutely certain regarding their diagnosis (Table 2). The diagnostic concordance between the two dermatologists was 97.7 percent and there was disagreement in 2.3 percent of the cases. There was near perfect agreement between the two dermatologists, and this agreement was statistically significant (weighted kappa = 0.977, p=<0.001) (Table 2).

Mean PQRS score of Dermatologist 1 (experience ≤5 years) was 6.22 ± 1.68 while the mean score of Dermatologist 2 (>5 years’ experience) was 6.24±1.71, the median being six in both the cases and mode being seven. Clarity was the parameter with the minimum score while color was the component with the maximum score. 82.4 percent of the patients were able to send clear images on first contact. In 73.6 percent of cases, no additional tests were ordered and diagnosis was made on the basis of image and the relevant history given by the patient alone. In patients in whom additional tests (e.g., skin biopsy, laboratory investigations) were ordered to make a diagnosis, the PQRS score was low (4.92) as compared to those in whom no additional test was required to make a diagnosis (6.69) meaning that when the diagnosis was not evident on clinical photograph alone, additional tests were ordered to make an accurate diagnosis. Most of these low scorers belonged to rural areas. Participants with absolutely certain diagnosis had a mean PQRS score of 6.9 while participants whose diagnosis was not certain had a mean PQRS score of 4.41 which was clinically significant. Patients in whom both the dermatologists were absolutely certain about their diagnosis had a higher PQRS score and interestingly also were more educated than the rest.

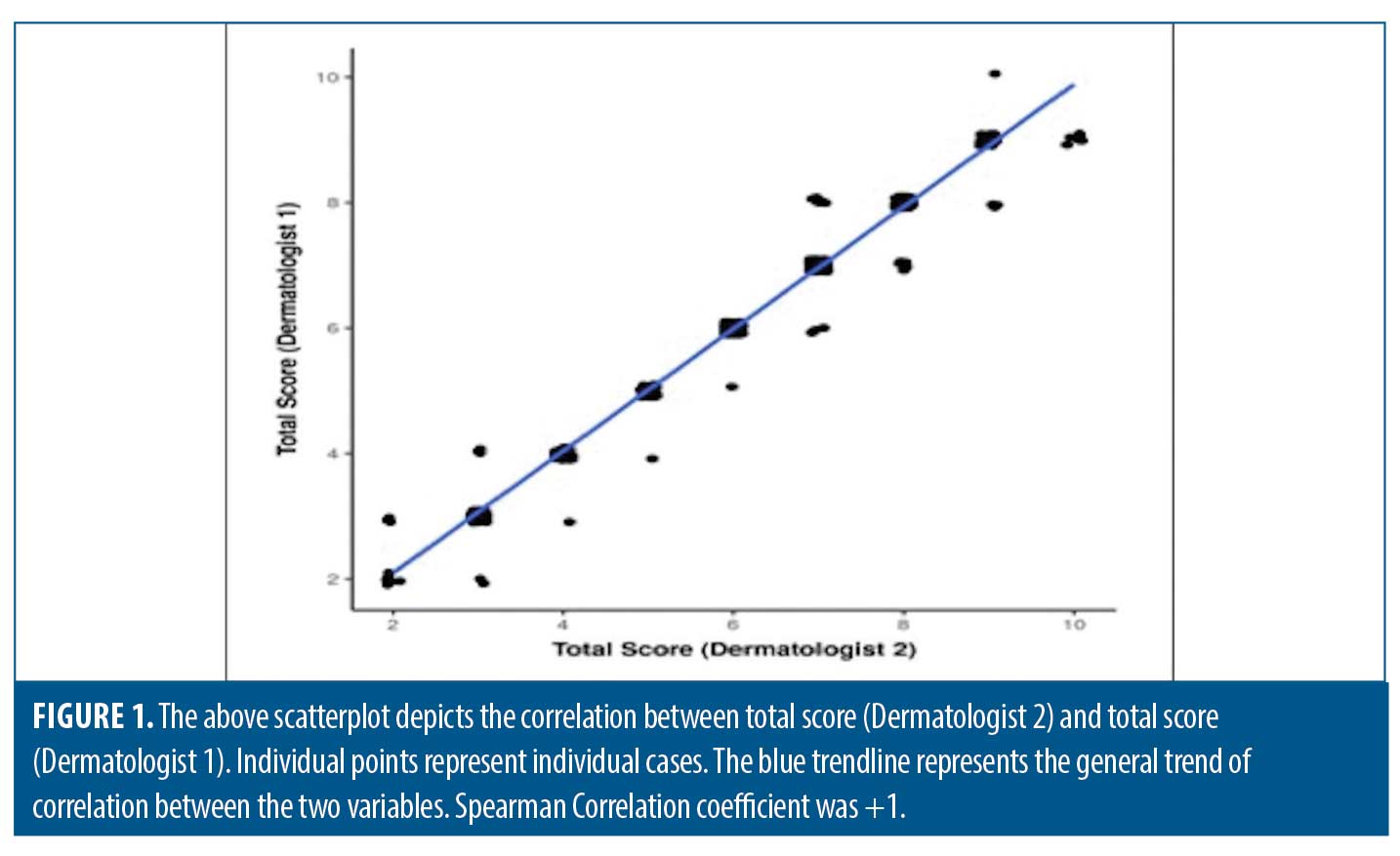

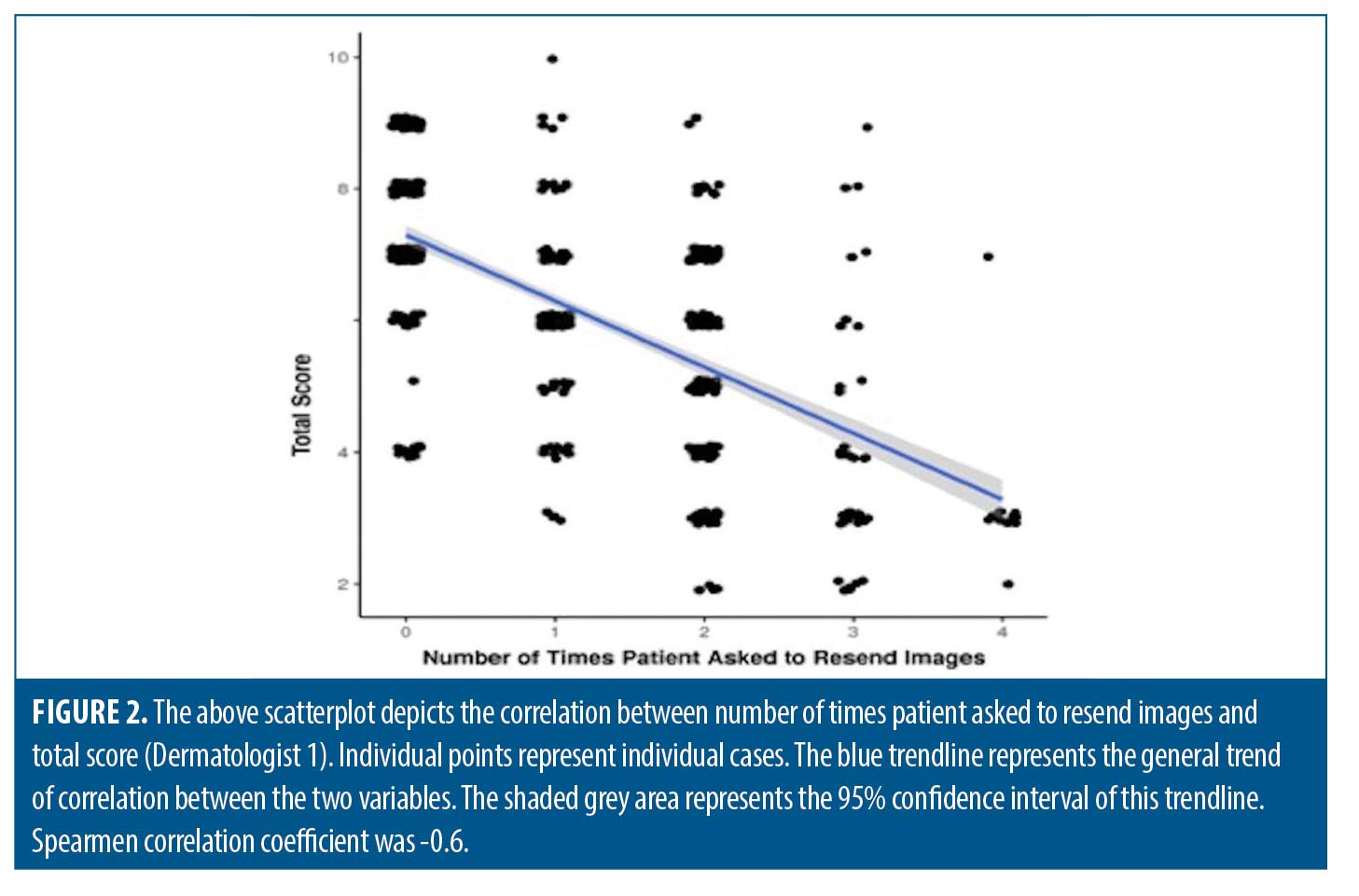

Correlation of total score between both the dermatologists was determined and it showed a very strong positive correlation (Figure 1) and this correlation was statistically significant (rho=0.99, p=<0.001). There was a strong negative correlation between number of times patient was asked to resend images and total score, and this correlation was statistically significant (rho=-0.62, p=<0.001). For every one unit increase in the number of times patient asked to resend images, the total score decreased by 1.00 units. Conversely, for every one unit increase in total score, the number of times patient asked to resend images decreases by 0.38 units (Figure 2).

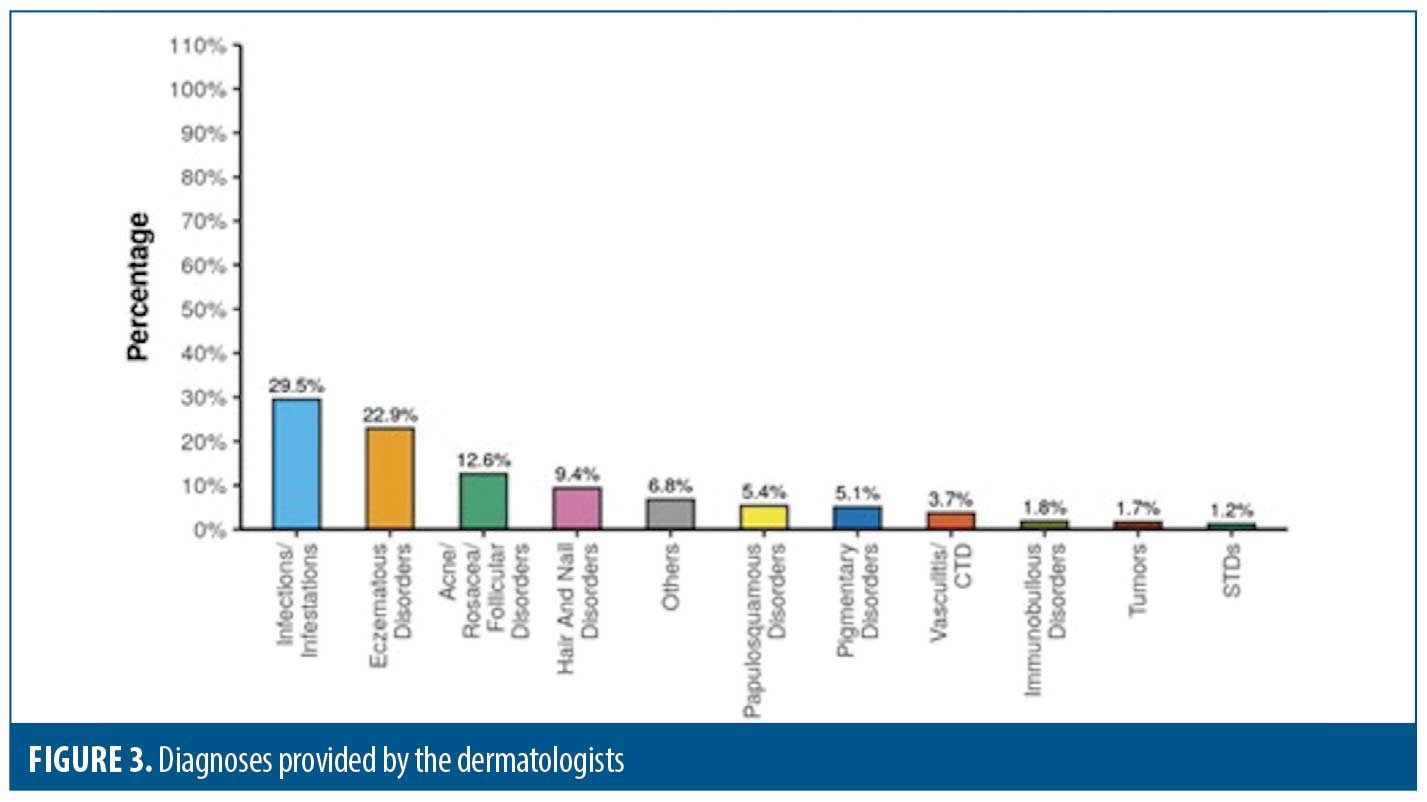

Infections and infestations comprised overall the most common group of diagnosis (Figure 3). Eczematous disorders, immuno-bullous disorders and vasculitis/connective tissue diseases were the most common diagnosis with PQRS score less than five and disagreement between the two dermatologists. Infections and infestations had the largest proportion of total score category more than five. Infections, acne, follicular disorders, pigmentary disorders, tumors, and STDs had the largest proportion of cases wherein both the dermatologists were in total agreement with each other.

Discussion

Skin, the largest organ of the human body, is unique in being available to the naked eye for examination. Many dermatological diseases have a characteristic clinical morphology making inspection the most important part of examination for diagnosis which makes it seem to be more amenable to telemedicine than the other branches of medicine where palpation, percussion and auscultation are also needed. Thus, patients presenting for teledermatology consultation during the pandemic spanned across various dermatoses similar to a physical OPD. Though for some patients diagnosis can be made based only on inspection others do require a physical consultation as dermatology is truly a three-dimensional specialty where touch, texture and volume are just as important as the visual assessment.

The most important factor pertinent for an accurate diagnosis in teledermatology is a good clinical photograph. The photograph should be clear, bright, and depictive of the disease. Thus, the present study has used a PQRS score to depict the quality of the image objectively. It incorporates the most important elements of a quality photograph and constitutes them into an objective score.13

O’Connor et al13 studied diagnostic accuracy of pediatric teledermatology using patient submitted photographs. The quality of the photographs was assessed by a PQRS score and the patients were divided into two groups, with 20 parent-patient dyads in each group. One group was given instructions about the correct way to send photograph to a clinician and the other group was not. They concluded that the overall concordance between photograph based and in person diagnosis was 83 percent and there was no statistically significant effect of photography instructions on concordance.

In the present study, PQRS score was high in educated persons and in people living in urban areas. Both these factors are inter-related and a high PQRS score is self-explanatory. As the number of times the patient sent images increased, the total score decreased which is contradictory but can be explained on the fact that as the patient was told to resend an image, he/she sent an image taken from a very close distance to the lesions which decreased its resolution and clarity, thus decreasing the score. Another interesting fact was that the number of years of clinical experience of the physician was not associated with the ability to make an accurate diagnosis. This may be because the diagnosis was based predominantly on the photograph and clinical acumen of the dermatologists’ did not play a major role in that.

Oakley et al14 studied 384 cases, of which 74 percent were diagnosed as inflammatory skin disease, 10 percent as cutaneous infection, 12 percent as nonspecific skin lesions, and no diagnosis was made in 4 percent cases. This study mentions an apparent success rate of 75 percent, with a positive feedback from the patients, but the authors mention that the service was not sustainable in the long term due to various factors like other priorities for the delivery of healthcare, lack of support by clinicians and administrators, and financial costs.14 Similarly the present study has a high concordance between the two dermatologists but we suggest a high future prospect for teledermatology.

Du Moulin et al15 observed that eczema and follicular lesions were diagnosed with relatively more certainty. This was contradictory to our study as in the present study eczematous disorders were diagnosed with low certainty.

Kaliyadaan et al16 studied 120 patients and found that the diagnoses were made with absolute certainty in cases like viral warts, herpes zoster, acne vulgaris, irritant dermatitis, vitiligo, and superficial bacterial and fungal infections. In cases where papulosquamous, chronic granulomatous, vesiculobullous conditions, and vasculitis were considered, certainty of diagnosis was low. In 70 cases, lab or radiological investigations were advised. Immediate referral to higher center was advised in only nine cases. This is similar to the present study which showed that diagnosis was made with absolute certainty in cases like infections while in conditions like vasculitis, immune-bullous disorders or eczematous disorders the diagnostic certainty decreased significantly.

In the present study, there was 97.7 percent diagnostic concordance between the two dermatologists. This percentage is higher as compared to other studies which may be because in the present study the teledermatology diagnosis could not be confirmed by in-person diagnosis. Cases where both the dermatologists made a diagnosis with absolute certainty had a higher PQRS score. There was diagnostic discordance in 2.3 percent cases which included cases belonging to eczematous disorders, vasculitis, connective tissue disorders or immuno-bullous disorders. These disorders, being chronic, have variable morphologic patterns and usually involve a large surface area which makes it difficult to be captured in a few clinical photographs. Most of these disorders require investigations like skin biopsy or immunofluorescence studies to make a definitive diagnosis. Diseases like infections, acne, pigmentary disorders, tumors and sexually transmitted diseases had high PQRS score and agreement between both the dermatologists, making them amenable to a teledermatological diagnosis. This may be because most of these diseases have characteristic clinical appearance and usually involve a specific site.

Conclusion

Teledermatology is a tool which reduces the time lag between the onset of the disease and time of consultation significantly. It saves travel time for both the doctor and the patient. Long waiting hours, especially in a government hospital, are overcome. This study highlights the various aspects of teledermatology. The ability to make an accurate diagnosis was directly proportional to the PQRS score. The PQRS score was further dependent on the education of the patient and the area in which he belonged to. Patients who were educated and belonged to an urban area had higher PQRS score and thus a high probability of an accurate diagnosis. PQRS score was independent of the age of the patient. Most of the patients were able to send quality images even without any instructions. In around 60 percent of the cases, there was absolute certainty regarding the diagnosis hence, it can be used as a triage in the post-covid era to sieve patients requiring emergency care and reduce patient wait times. Teledermatology may be best for the care of patients with characteristic clinical presentation or for follow-up of already diagnosed patients. Diseases like infections, acne, pigmentary disorders, tumors and sexually transmitted diseases have a characteristic clinical appearance, thus making them amenable to a teledermatological diagnosis.The quality of photographs and thus the ability to make a diagnosis was dependent on multiple factors including education of the patients.

Limitations. The limitations of the present study are that it was a retrospective study and the diagnoses which were made were not confirmed by face-to-face consultation.

References

- Perednia DA, Allen A. Telemedicine technology and clinical applications. JAMA. 1995; 273: 483–488.

- Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375(2): 154–161.

- Whited J. Teledermatology research review. Int J Dermatol. 2006; 45: 220–229.

- Heffner VA, Lyon VB, Brousseau DC, et al. Store-and-forward teledermatology versus in-person visits: a comparison in pediatric teledermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009; 60(6): 956–961.

- Reeves JJ, Hollandsworth HM, Torriani F, et al. Rapid response to COVID-19: health informatics support for outbreak management in an academic health system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020; 27: 853–859.

- Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl Med. 2020; 382 (18): 1679–1681.

- Philp JC, Frieden IJ, Cordoro KM. Pediatric teledermatology consultations: relationship between provided data and diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013; 30(5): 561–567.

- Vallejos QM, Quandt SA, Feldman SR et al. Teledermatology consultations provide specialty care for farmworkers in rural clinics. J Rural Health. 2009; 25: 198–202.

- Eedy DJ, Wootton R. Teledermatology: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144: 696–707.

- Fogel AL, Teng JMC. Pediatric teledermatology: a survey of usage, perspectives, and practice. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015; 32(3): 363–368.

- Thomas J, Kumar P. The scope of teledermatology in India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013; 4: 82–89.

- Warshaw EM, Hillman YJ, Greer NL, et al. Teledermatology for diagnosis and management of skin conditions: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 64: 759–772.

- O’Connor DM, Jew OS, Perman MJ, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Pediatric Teledermatology Using Parent-Submitted Photographs: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2017; 153: 1243–1248.

- Oakley AM, Rennie MH. Retrospective review of teledermatology in the Waikato,1997-2002. Australas J Dermatol. 2004; 45: 23–28.

- Du Moulin MF, Bullens-Goessens YI, Henquet CJ, et al. The reliability of diagnosis using store-and-forward teledermatology. J Telemed Telecare. 2003; 9: 249–252.

- Kaliyadan F, Venkitakrishnan S. Teledermatology: Clinical case profiles and practical issues. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009; 75:32.