J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(6 Suppl 1):S27–S29

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(6 Suppl 1):S27–S29

by Purva Pande MD; Sree Ramu Suggu, MD; and Mala Bhalla, MD

All authors are with the Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprosy at the Government Medical College and Hospital in Chandigarh, India.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for the preparation of this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Vitiligo affects one percent of general population and usually manifests in the second and third decades of life. Vitiligo is believed to be an acquired condition, though a positive family history is seen in 30 to 40 percent of cases. Few cases of vitiligo at birth have been reported. We report a case of congenital vitiligo in a neonate and discuss disease course and pathogenesis.

Case report. A 27- days-old female neonate patient presented with multiple, rapidly progressing, depigmented patches over the body that had been present since birth. The lesions showed chalky white accentuation under Wood’s lamp. There was positive history of vitiligo in the mother. The child was started on topical fluticasone propionate 0.05% cream in the morning and tacrolimus 0.03% ointment at night. At the one-year of follow-up period, there were no new lesions, and partial repigmentation was noticed in the existing lesions.

Conclusion. Manifestation of vitiligo at birth is a very rare occurrence. The presentation at birth in this case suggests a genetic link, as opposed to acquired factors, and supports the in-utero hypothesis, adding to the scant literature available on congenital vitiligo.

KEYWORDS: Vitiligo, pigmentary disorders, dyspigmentation

Vitiligo is a benign chronic depigmenting disorder of the skin. It has a prevalence rate of 1 to 2 percent in the general population, with no predilection by sex, race, or region.1 Though the exact etiopathogenesis of vitiligo is unknown, it is hypothesized to be a multifactorial process involving the interplay of genetic, autoimmune, environmental, and neurogenic factors. Vitiligo usually manifests in the second or third decade of life and is believed to be an acquired condition, though a positive family history is present in 30 to 40 percent of cases.2 Congenital vitiligo and presentation at birth is a very rare entity, but cases in infancy have been reported.3 Due to its rare occurrence, there is a lack of data on congenital vitiligo, and little is known about its exact etiopathogenesis and evolution. The known psychosocial impact of vitiligo warrants more vigorous research into this disorder and increasing the scant knowledge with respect to congenital vitiligo. Hereby, we report a case of congenital vitiligo in a neonate patient, who presented with multiple hypopigmented to depigmented patches all over the body, which had been present since birth.

Case Report

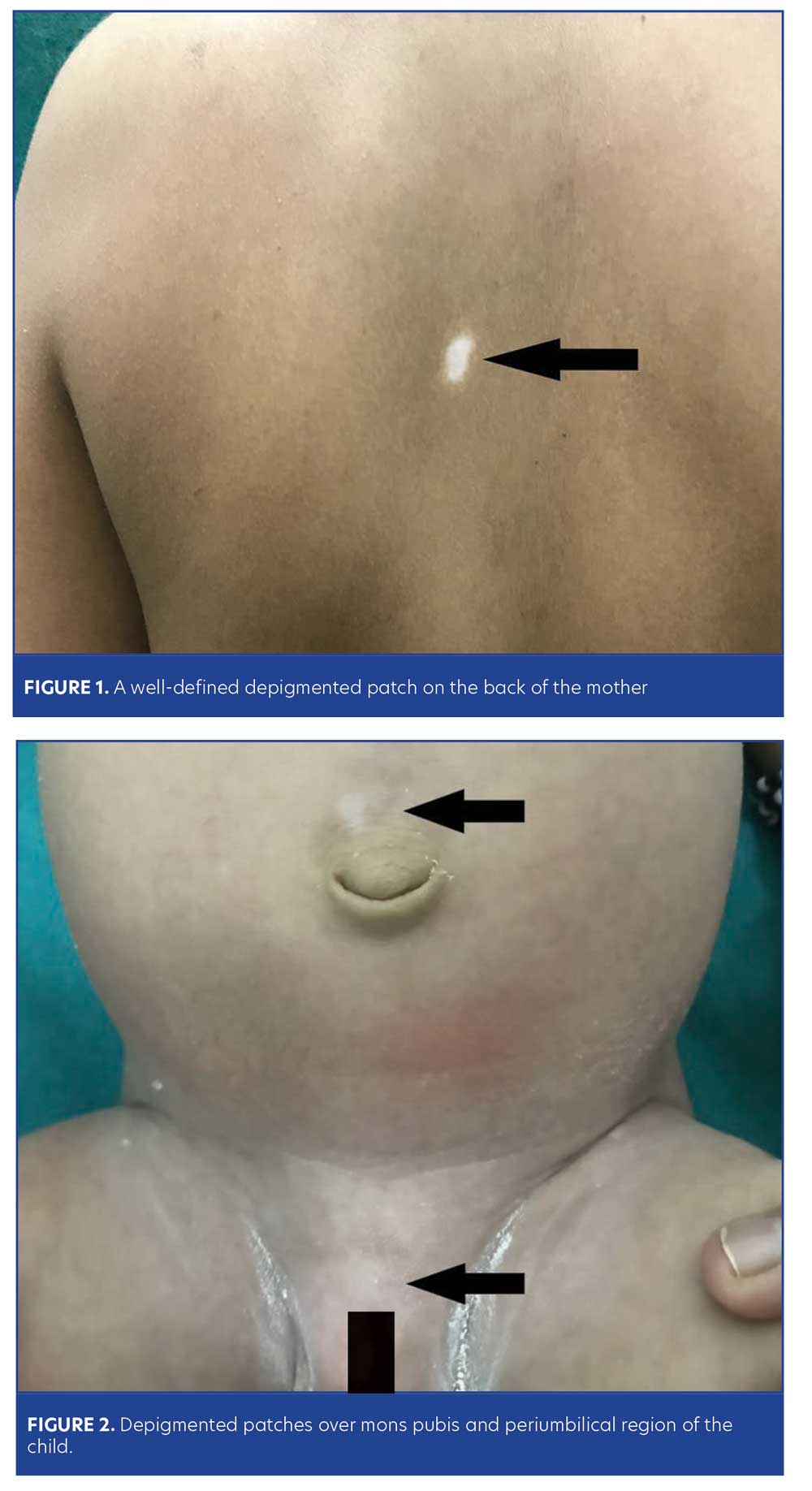

A female neonate patient, aged 27 days, was brought into the clinic by her mother due to presence of multiple white patches over the body, which had been observed since birth. The lesions were first observed on the mons pubis region, but had progressed to other body parts. The patient was the only child of her parents and was born by a normal vaginal delivery with an uneventful perinatal history. The child was healthy, eating and passing urine and stool normally. There was no history of seizure. The mother was not on any medication, though she had a positive history of vitiligo (stable for the last five years) (Figure 1). The thyroid profiles of the baby and the mother were within normal limits.

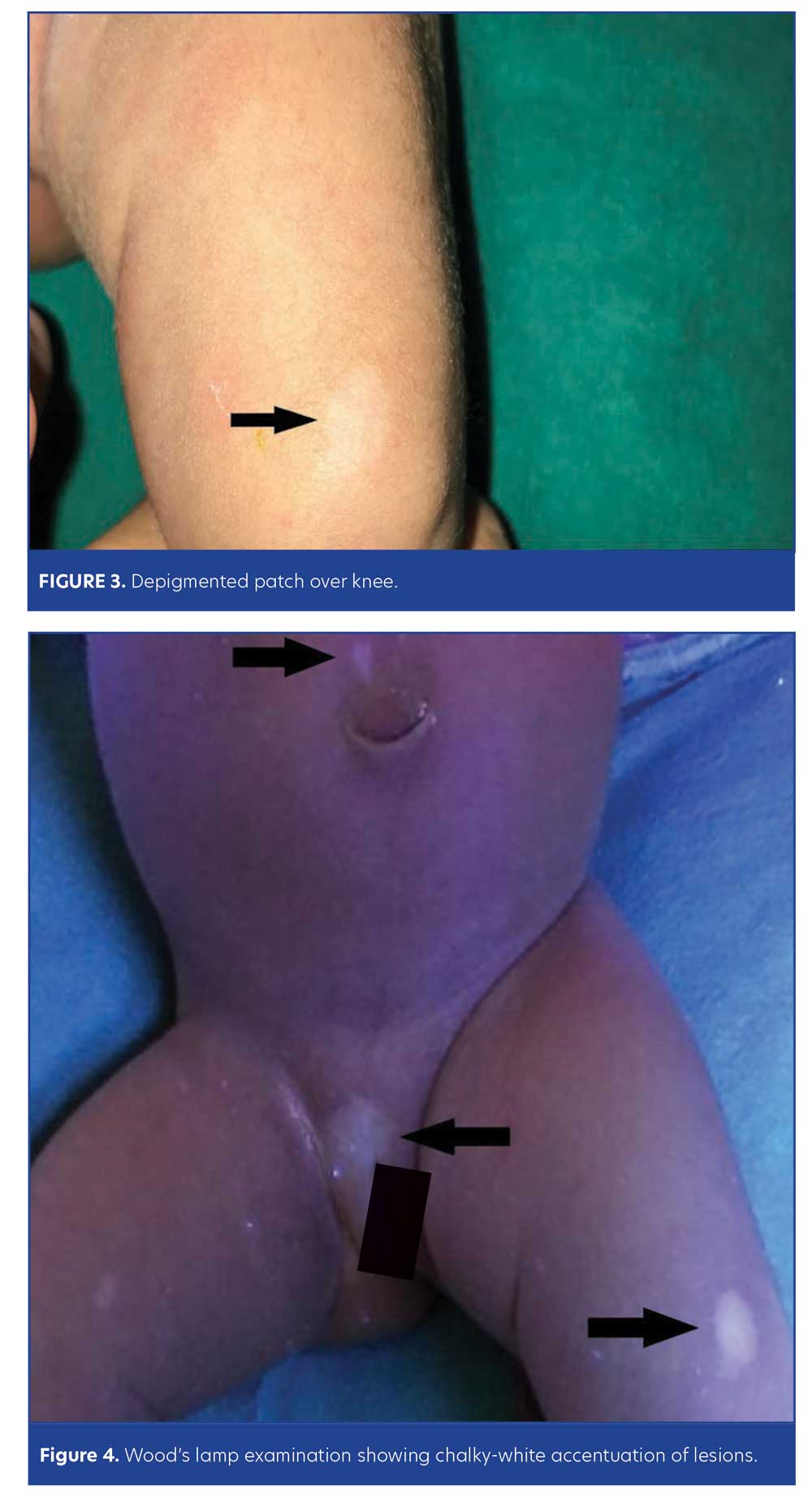

Examination of the infant revealed multiple, well-defined, asymptomatic, hypopigmented-to-depigmented patches of skin with regular borders on the mons pubis, vulva, abdomen, and both knees, ranging in size from 0.5cm by 0.5cm to 5cm by 3cm (Figures 2 and 3). The lesions showed no surface differences. Woods lamp examination revealed chalky-white accentuation of the lesions (Figure 4). The infant showed no ocular or hair abnormalities.

The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented to depigmented lesions in a neonate include nevus depigmentosus, hypomelanotic macules of tuberous sclerosus, piebaldism, and hypomelanosis of Ito—all of which were excluded due to the presence of multiple, discrete, non-blaschkoid lesions with well-defined margins and absence of white forelock, cutaneous features of tuberous sclerosis, neurological symptoms, or any other systemic complaints. Based on the classic cutaneous lesions, their progression, a positive family history, and accentuation of the lesions on Wood’s lamp examination, a diagnosis of congenital vitiligo was made.

The parents were counseled on the disease. The infant was started on topical fluticasone propionate 0.05% cream in the morning and tacrolimus 0.03% ointment at night. At the one-year of follow-up period, there were no new lesions, and partial repigmentation was noticed in the existing lesions.

Discussion

Vitiligo, characterized by depigmented patches of skin over the body, is believed to be an acquired pigmentary disorder in which genetic susceptibility plays an important role. The majority of cases present during the young adult life; congenital cases have been rarely reported.2 The other conditions that present with hypopigmented to depigmented patches in a neonate patient are hypomelanotic macules of tuberous sclerosis, piebaldism, hypomelanosis of Ito, and nevus depigmentosus.4

Despite the large body of research on vitiligo, its exact etiopathogenesis remains unclear. The most widely accepted theory is that vitiligo is multifactorial, occurring when other genetic conditions are present that predispose vitiligo macules to occur as a result of specific environmental factors (the exact nature of which is still unknown).5,6 A few of the implicated factors are puberty, pregnancy, major infections, dietary imbalance, stress, and skin trauma, which might precipitate the first symptoms of the disease. There is a 7- to 10-fold increased risk of vitiligo in first-degree relatives of someone with the disease.7,8 There is also a hypothesis that the autoimmune process might be initiated in-utero in genetically susceptible individuals.3

Many studies have confirmed significant pathogenic participation of candidate genes PTPN22 and HLA in the development of vitiligo. Candidate gene association studies have confirmed the association of XBP1, FOXP3, and TSLP with vitiligo.3 Approximately 36 convincing nonsegmental vitiligo susceptibility loci have been identified, most of which are localized directly within or in close proximity to reliable biological candidate genes. Approximately 90 percent of them encode immunoregulatory proteins, while 10 percent encode melanocyte proteins. The proteins of melanocyte might act as auto-antigens activating specific immune response and are expelled by the immune system.9

Manifestation of vitiligo at birth is very rare. Presentation of vitiligo at birth in our case supports the theory that various genetic factors are involved, as opposed to only acquired factors. Existing evidence of congenital vitiligo is scarce due to the rarity of this presentation. Our review of the available literature revealed only seven published case reports of congenital vitiligo to date. Out of the seven published case reports, five of the cases showed predominant acral distribution of the lesions that were more stable/nonprogressive.3,4,10 Our case showed rapidly progressing multiple patches over the body, around the orifices, and at friction sites at the time of presentation, which is more consistent with the clinical picture of vitiligo vulgaris.

Conclusion

The present case supports the hypothesis that the autoimmune process might be initiated in-utero in genetically susceptible individuals, and adds to the scant literature available on congenital vitiligo. Our case suggests the importance of koebnerisation in congenital vitiligo, as both the acral sites and the sites involved in our patient are more prone to skin trauma in-utero. More extensive research is needed to increase our understanding of the etiopathogenesis and clinical course of congenital vitiligo.

References

- Lerner AB, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. What is it? Is it important? JAMA 1978;239(12):1183–1187.

- Kakourou T. Vitiligo in children. World J Pediatr. 2009;5:265–268.

- Kambhampati BN, Sawatkar GU, Kumaran MS, Parsad D. Congenital vitiligo: A case report. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20(4):354–355.

- Barro M, Diallo JW, Outtara AB, Nacro B. Congenital vitiligo: A case observed in the cohort of HIV- exposed infants in Bobo- Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Pediatr Rep. 2017;9(3):7300.

- Spritz RA. Recent progress in the genetics of generalized vitiligo. J Genet Genom.

2011; 38(7):271–278. - Boissy RE, Spritz RA. Frontiers and controversies in the pathobiology of vitiligo: separating the wheat from the chaff. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(7):583–585.

- Bhatia PS, Mohan L, Pandey ON, et al. Genetic nature of vitiligo. J Dermatol Sci.

1992;4(3):180–184. - Nath SK, Majumder PP, Nordlund JJ. Genetic epidemiology of vitiligo: multilocus recessivity cross – validated. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55(5):981–990.

- Czajkowski R, Mecinska-Jundzill K. Current aspects of vitiligo genetics. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31(4):247–255.

- Casey C, Weis SE. Insight into natural history of congenital vitiligo: a case report of a 23-year-old with stable congenital vitiligo. Case Reports in Dermatological Medicine. 2017;8:1–3.