J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(1 Suppl 1):S4–S11.

by Patricia K. Farris, MD, FAAD, MS; Dendy Engelman, MD, FACMS, FASDS, FAAD; Doris Day, MD, FAAD, MA; Adina Hazan, PhD; andIsabelle Raymond, PhD

Introduction

by Patricia K. Farris, MD

Hair thinning is a complex issue that generates significant concern for those who are affected. Patients exploring medical treatments are offered conventional options that provide variable results and may be associated with side effects. Our first line of treatment for men usually involves topical minoxidil, which has low adherence rates due to effects on hair texture and styling and because it can cause scalp irritation. Alternatively, 5-α reductase inhibitors, such as finasteride or dutasteride, may be prescribed. These oral medications are effective for thinning hair, although many men are reluctant to take them due to the possibility of sexual dysfunction and decreased libido. More recently, low dose oral minoxidil has been used off label, and while it is effective, it can cause side effects such as hypertrichosis and pedal edema. In addition, oral minoxidil must be used with caution in patients with a history of hypertension or who are at risk for cardiovascular disease. Women have comparable numbers affected by hair thinning. There are fewer United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medical treatment options for women and most all of them are treated with off-label medications.

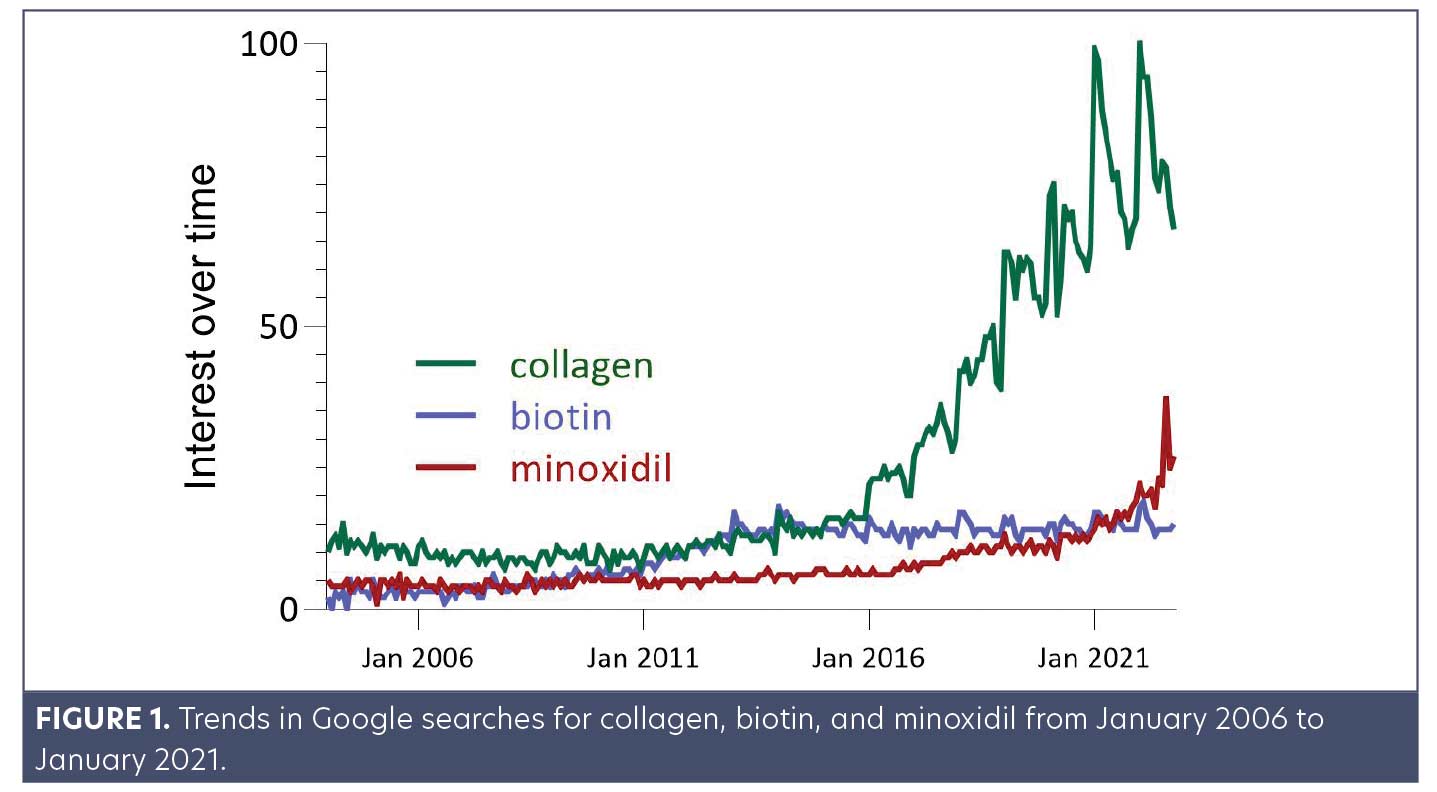

Patients are increasingly turning to more accessible, over-the-counter solutions for thinning hair. Natural therapies are favored by consumers who are looking for ingredients that target hair growth and aim to improve underlying health and wellness without unwanted side effects. The trends of Google searches in the Beauty and Fitness category demonstrate that minoxidil, biotin, and collagen were all among products increasingly searched over the last 10+ years (Figure 1). Moreover, before 2016, minoxidil, biotin, and collagen were searched equally. Over the last few years, interest in collagen supplementation has increased.

Unfortunately, there is an enormous gap between the number of supplements available with unsubstantiated claims versus products with evidence-based backing. Google searches, social media, and word of mouth spread misinformation to millions of users within hours. With a plethora of unsupported hair supplements on the market, more patients are seeking advice from healthcare professionals to understand what is helpful, what is ineffective, and what is potentially dangerous. Thus, it is prudent for dermatologists to keep informed on the research supporting nutraceutical solutions. In this supplement, we present and review the data behind two top trending natural ingredients touted for hair growth—biotin, and collagen.

The Infatuation with Biotin

by Dendy Engelman MD, FACMS, FASDS, FAAD

Recent studies show that 29 percent of consumers take biotin-containing supplements, and that 43.9 percent of physicians and dermatologists recommend biotin to address predominantly hair (59%) and nail (86.9%) concerns.1,2 But do the data support these recommendations?

What is Biotin?

Biotin, or vitamin B7, is an essential part of the metabolism of fatty acids, carbohydrates, and amino acids. It helps break down food into glucose, the main energy source for the body and brain, and plays a role in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, chromatin stability and gene expression, and regulation of oxidative stress.3,4 Biotin is also an essential co-factor for mitochondrial carboxylases in hair roots.

The adequate intake of biotin established by the FDA is 30mcg/day, and most people consume an estimated 35 to 70mcg/day.5 This is because biotin is found in many foods, including chicken, eggs, nuts (e.g., peanuts, almonds), and cheese. Plus, bacteria in the large intestine can synthesize enough biotin for the body even without getting it from food.6 Considering this, biotin deficiency is rare and generally only found in at-risk populations, such as in those with chronic alcohol use, patients on long-term anticonvulsant therapy, and those with genetic conditions that affect the absorption and metabolism of biotin.4,5,7 For special consideration for dermatologists, low biotin levels have also been reported during prolonged use of oral antibiotics (such as is prescribed to treat acne), as well as in patients taking isotretinoin for acne.4,8

Biotin’s role in hair, skin, and nails

Biotin’s role in hair, skin, and nails comes from early studies published in which biotin supplementation improved hair and skin conditions in select cases. In one example from 1985, a boy with uncombable hair syndrome—a condition that presents with thin, unmanageable, and usually blonde hair, and mostly seen in children— was given a biotin supplement.9 This was reported to clear his scalp from dandruff and improve his hair and nail growth and strength within a few months.9 Other reports were taken from studies showing improvement in horse hoof structure.10

More recent studies show that biotin plays an essential role in energy production at the hair root. Hair follicles replicate at an extremely fast rate, requiring high levels of energy.11 Biotin is an essential factor in keratin synthesis, thus contributing to healthy hair, skin, and nails. It is also required for fatty acid metabolism in the skin. Deficiency, although rare, can lead to alopecia, periorificial dermatitis (a scaly red rash around the eyes and mouth), conjunctivitis, and skin infections.6 These clinical manifestations from low biotin highlight the importance of biotin in hair and skin health.

Biotin Oral Supplementation

Biotin supplementation has been shown to be essential for patients with biotin deficiency, but evidence to support that excess biotin well above normal limits improves hair growth is scanty at best.6,12,13 To date, there have been no comprehensive clinical trials showing that biotin supplements alone, in individuals with no underlying conditions consuming a normal diet, improves hair growth.14 In a recent review of 18 cases in which biotin use improved hair and nails, all 18 individuals had underlying links to biotin deficiency, such as genetic causes or brittle nail syndrome.15 In cases where a deficiency is present, biotin does improve hair and skin conditions. But most women complaining of hair loss are not biotin deficient. In a recent study of 541 women complaining of hair loss, only 38 percent were deficient in biotin.16 Of those deficient, 11 percent had a personal risk factor for biotin deficiency, such as isotretinoin medication, showing that in the majority of cases, hair loss is a multi-factorial process that cannot be attributed to a single cause.16

In contrast to hair, there is some evidence emerging that biotin supplementation improves nail strength and growth, although the mechanism and effective doses have yet to be fully elucidated. A recent study in healthy adults with no underlying nail disorders compared 5% topical minoxidil and 2,500mcg oral biotin. Their results showed improvements in nail growth rate with both treatments, although minoxidil produced a greater growth rate increase.17 Nail firmness has also been shown to improve in adults with brittle nails treated with 2,500 mcg daily.18 Beyond the few limited studies available, more clinical trials are needed to make evidence-based recommendations on the role of biotin supplementation in improving nail growth and quality.

The recommended daily intake (RDI) of biotin ranges from 30 to 70mcg per day, and there is no known toxicity or upper limit even at 10,000 times the RDI.5,16 We know this because at these doses, biotin improves clinical outcomes and quality of life in patients with progressive multiple sclerosis (MS).19

While not toxic, in 2017 the FDA issued a warning that excessively high biotin consumption can cause false lab results.20 This warning was issued based on a case study of a patient with MS who was taking at least 300,000mcg of biotin. Since then, the FDA has cited special concern for readily available supplements containing exorbitantly high levels of biotin, such as 20,000 to 100,000mcg in a single pill, with instructions to take multiple pills per day. Biotin taken at these doses has been shown to interfere with biomarker detection during diagnostic testing, producing false negative or positive lab results. Specifically, the FDA reports that circulating biotin can reach as high as 1,200ng/mL, interfering with troponin assays and producing a “false negative” for the suspicion of a heart attack. In 2019, the FDA reiterated the concern and provided further recommendations for manufacturers of these assays to address this concern in their lab tests. Other biomarkers that may be affected include 25-OH vitamin D, human chorionic gonadotropin, thyroid hormones, hepatitis, or HIV tests.19,21 Despite the FDA announcements, approximately 1 in 5 physicians (19.5%) are unaware of the potential interference of biotin in lab results.2 It is critical here to recognize that targeted efforts are needed to continue to educate physicians and consumers about the nuances of taking a dietary supplement like biotin and its potential secondary effects. This in part comes from understanding how biotin interference affects biochemical assays. The assays which are affected utilize the incredibly strong bond between biotin and a molecule called streptavidin. Excess biotin in the patient sample binds and blocks the streptavidin site, so that the biochemical analyte does not bind, changing the result of the assay.22 The effect can be either an artificial increase or decrease, depending on the type of assay.22 Each assay has a different interference threshold depending on the type and manufacturer, but the highly sensitive assays are generally considered 30ng/mL or less.22 Table 1 details select immunoassays with reported biotin interference and their threshold of interference.

Practically speaking, biotin is a water-soluble molecule, meaning that it is metabolized and excreted rapidly from the body. Pharmacokinetic studies show that even after taking 20mg of biotin, the peak serum concentration occurs in less than an hour.23 Moreover, a recent study in 54 healthy individuals showed that serum biotin levels in all participants dropped below 30ng/mL within eight hours after consuming 10,000mcg.23 Therefore, to combat the effect of biotin in lab tests, it is generally recommended that patients who have consumed 5,000 to 10,000mcg of biotin wait a minimum of eight hours before having blood collected for laboratory tests.23 Accumulation does occur when taking a daily dose of biotin, but again, this is dose-dependent and less of a concern when taking less than 5,000mcg per day.21,23 Longer washout periods, up to 72 hours, may be required to prevent interference in patients on high-dose therapy (≥100,000 mcg/day) and for assays with low interference thresholds (<30 ng/mL).22,23 Table 2 details recommended clearing times for various dosages of biotin.

It has been five years since the FDA put out their first warning, but a quick search for biotin supplements still reveals many 5,000 to 10,000mcg options and “high dose” bottles with 100,000mcg available. Most consumers who turn to these supplements believe that biotin at these levels will promote healthy hair, skin, and nails. It is important to emphasize that this does not have to be an all-or-none situation. As a co-factor in combination with other vitamins and nutraceuticals, it has shown efficacy in improving hair growth.24

Overall, biotin is an essential component of skin, hair, and nails. In the general population, a balanced intake of nutritional foods provides the amount of biotin needed to support healthy and strong growth, and supplementing with biotin is generally considered safe. As with most nutrients, more is not always better. Excessive biotin dosages of 5,000mcg or more, well beyond the RDI, does not provide additional benefits and can interfere with diagnostic testing.21 This balance highlights the important distinction between anecdotal claims using inordinate supplements that are widely available versus scientifically backed, evidence-based medicine.

The Latest Trend: Collagen Supplements

by Doris Day MD, FAAD, MA

What is Collagen?

Collagen is the most abundant protein in the human body. It is a large, fibrous scaffold forming the structural component in the hair, skin, bones, joints, and tendons. It provides strength, bridges gaps between cells and extracellular matrices, and modulates inter-cellular networks. There are over 27 types of collagen, distinguishable by their structure, function, and location in the body. The most abundant types are I, II, and III, with I and III being the prominent forms in the skin and hair.25,26

The collagen structure is built to provide mechanical support starting on the molecular level. Each collagen molecule is made up of three intertwined strands of about 1,000 amino acids per molecule. The intertwining fibers are a repetitive pattern forming a rope-like, triple helix structure. The fibers are made up of a repeating pattern of the small amino acid glycine at every third position, which provides the flexibility to bend into the helical structure. The other amino acids which combine to form the ropes are proline, hydroxyproline (22%), or hydroxylysine. Stability between the helices comes from intermolecular bonds from the lysine.25

Collagen is produced in mesenchymal cells, specialized cells that form and maintain the connective tissue all over the body— dermal fibroblasts (skin, hair), chondrocytes (bone and cartilage), osteoblasts (bone), odontoblasts (teeth), and cementoblasts (follicle cells around the tooth).25 It is synthesized first as individual chains from repeating patterns of amino acids, which then align and intertwine to form the triple helix, giving it tensile and mechanical strength.

Once synthesized, collagen in adults does not turn over very often: type I found in the skin only degrades about 50 percent every ten years.27 The repetitive structural pattern and slow rate of turnover is partially what makes collagen particularly prone to damage over time.

Collagen’s role in hair and skin

Collagen accounts for about 70 percent of the skin’s dry weight.28 The strong, intertwined ropes provide a support matrix for elastin and hyaluronic acid.28 When intact, this network maintains elasticity and hydration to the skin, scalp, and hair follicle.28 During injury, the collagen scaffold is a necessary and major part of the repair and remodeling of the extra-cellular matrix.29 As we age, the amount of collagen in our body decreases by about one percent per year starting around age 30.30 The structural support of the skin shrinks, fine lines, wrinkles, and dull skin appear.28 Microscopically, the dermal collagen network becomes disrupted and accumulates shortened and disorganized collagen fibers.28 The fibroblasts and other cells which synthesize new collagen slow down, unable to keep up with the demand needed for the dermal layer.28

Another mechanism of aging comes from the build-up of advanced glycation endproducts, or AGEs.27 These form when circulating sugars combine with proteins or nucleic acids and contribute to collagen breakdown in two major ways: First, they form unintended, spontaneous bonds between AGEs and the tight collagen helices, disrupting the strong helical pattern and decreasing the mechanical strength of the collagen molecule.27 Second, circulating AGEs can trigger the production of reactive oxygen species and inflammatory pathways, leading to the breakdown of the collagen structure.31,32

In fact, people with type II diabetes are particularly affected by AGE cross-linking damage, as the high levels of circulating sugars more readily bind to the collagen molecules.27 Because collagen has a very slow turnover rate, these disruptions remain in place for very long periods of time, ultimately weakening the skin, hair, and nails.25,27 AGEs also attach to dermal papilla—cells located at the base of the hair follicle—which are responsible for the growth and cycling of the hair. This causes oxidative stress and an inflammatory response, accelerating the breakdown of collagen.33 As aging depletes collagen stores, there is less intact, complete collagen to replace and repair the damaged collagen from AGEs.

Evidence for Oral Supplementation

Increasing collagen consumption, either through eating collagen-rich foods or through oral supplementation, has been shown to be clinically effective in improving hair, skin, and nail health.34 Foods high in collagen include bone broth, fish, chicken, egg whites, leafy greens, and the algae spirulina. Otherwise, studies have shown that supplementing a normal diet with oral collagen is an effective way to increase the supply of collagen peptides delivered through the bloodstream.35

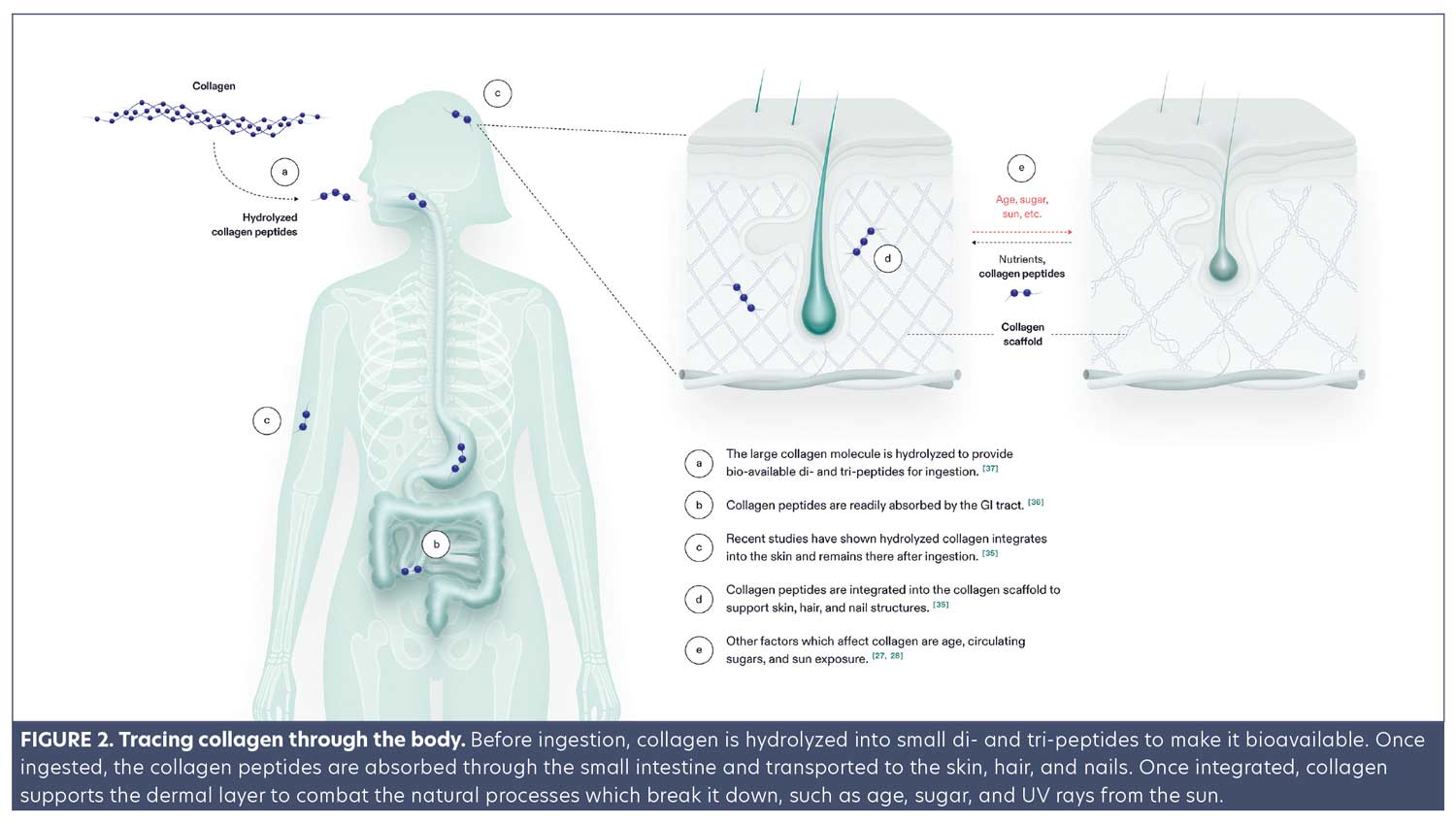

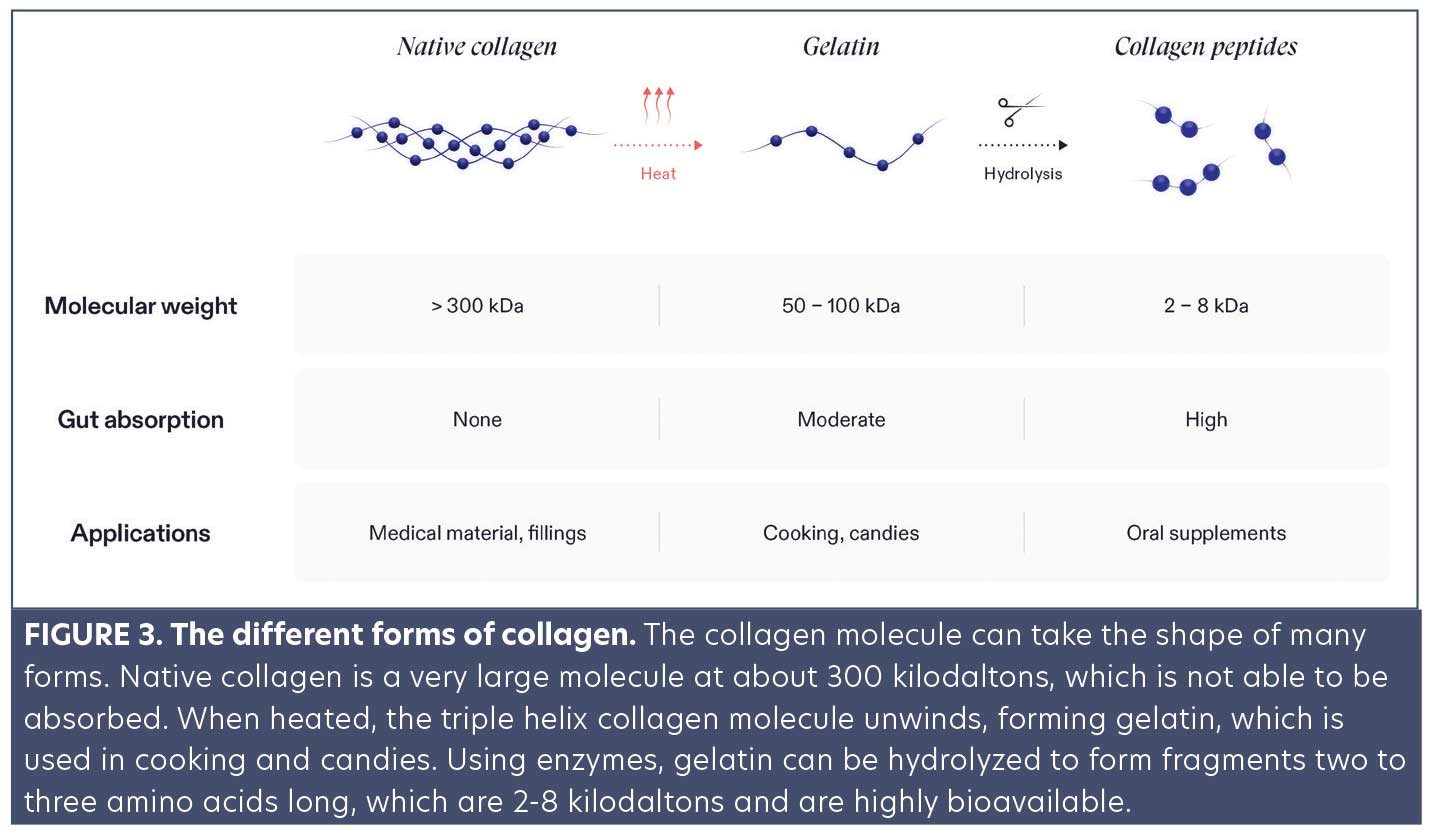

As with any supplement, though, the efficacy of supplemental collagen depends on the form, source, and quality of the collagen. Not all forms of collagen are readily bioavailable when ingested, adding controversy to the value of oral supplemental collagen. Because native collagen is such a large and complex protein, the molecule in its entirety cannot pass directly from the digestive tract to the bloodstream. Instead, collagen must first be denatured by heat (turned into gelatin), and then hydrolyzed (cut by enzymes) into short fragments only two or three amino acids long. These di- and tripeptides are predominantly made up of the amino acids proline, glycine, and hydroxyproline, the building blocks of collagen, and have low molecular weights of 3 to 6kDa. In this form, the collagen fragments are water soluble and easily absorbed and distributed in the human body—studies have traced these fragments after ingestion and have confirmed that they appear in the bloodstream and then integrate into the skin.35,36

The quality and type of collagen also depends on the source and tissue. Collagen supplements generally come from three sources: bovine (beef, tendon, ligaments, or lung), porcine (pig, skin), or marine (fish scales).37 Marine sourced hydrolyzed collagen peptides provide type I and III collagen peptides that also typically have lower molecular weight, improving absorption.37 It also has low inflammatory profiles and fewer concerns of biological contaminants that come with traditional animal derived sources such as toxins, viruses, or bacteria. There are also fewer religious concerns with collagen derived from fish rather than bovine or porcine sources. Because collagen is found in the byproducts not generally consumed from fish such as scales and viscera, it can be sustainably sourced.37

Mechanistically, there is a dual action proposed for the benefits of oral hydrolyzed collagen supplementation. First, it integrates into the skin and provides amino acids—the building blocks—used by the fibroblasts to form new collagen. In doing so, it reduces the fragmentation of the dermal collagen layer and reduces the signs of aging.35 Second, collagen peptides bind to fibroblast membrane receptors and trigger signaling cascades for new collagen synthesis at the level of mRNA transcription and protein translation.37 In addition, hydrolyzed collagen peptides have different functional properties, such as antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, depending on the degree of hydrolysis and the enzyme used. Specifically, proline-hydroxyproline dipeptides have been shown to stimulate chemotaxis and cell proliferation, enhance hyaluronic acid production, and increase water content in the stratum corneum.37,38

Because of the complex nature of the forms and sources of collagen, the benefits of oral supplementation as a clinical tool are still being investigated. Despite this, oral collagen supplements have clinically demonstrated positive effects on the skin: a recent meta-analysis of 19 randomized control trials of 1,125 participants showed favorable results in skin hydration, elasticity, and wrinkles.38,39 Ingestion of hydrolyzed collagen also reduced skin aging.39 While there is limited data on collagen supplementation for improving hair, there are reports that show increased thickness and decreased dryness and dullness.34 Studies also showed collagen supplements increase nail growth and improve nail strength, preventing breakage.34 It does so in a dose-dependent manner: increasing the amount of collagen intake (within the therapeutic range) will increase the amount of collagen integrated into the dermal layer.35

Overall, even though there is still work to be done on establishing the clinical efficacy of hydrolyzed oral collagen supplement, there is enough data to acknowledge it as an important tool in promoting skin, nail, and hair health. More controlled trials are needed, specifically on the source, form, and quality of collagen to understand the full benefits of supplemental oral collagen.

Natural Hair Supplements: One Size Does Not Fit All

by Patricia K. Farris MD; Doris Day, MD, FAAD, MA; Dendy Engelman, MD, FACMS, FASDS, FAAD; Adina Hazan, PhD, and Isabelle Raymond, PhD

Biotin and collagen are two of the most recommended and contested supplements for hair, skin, and nail health. Each are essential for the health of an individual, even beyond beauty concerns. Biotin deficiency, although rare, leads to skin and hair conditions, highlighting the importance of biotin as a co-factor in overall health. Collagen depletion starts at age 30, making the consumption of collagen-rich foods or supplements essential for combatting the aging process over time. That being said, a thorough literature search reveals the complexity of recommending these as supplements to improve hair health. Despite their growing popularity, there is a paucity of data supporting their efficacy as solo agents for hair loss. It is clear that neither of these supplements on their own can address all of the underlying aspects of hair health. There is no clinical evidence that biotin supplementation on its own, in a healthy population, improves hair. Moreover, “fire hosing” doses of biotin more than 10,000 times the RDI can affect lab tests.

On the other hand, there is emerging clinical evidence that supplemental collagen improves skin and hair health, yet the industry standards for the form, source, and quality of the supplement make determining the benefits difficult to extrapolate. A high quality, hydrolyzed collagen enhanced with additional ingredients that have select mechanisms specifically targeting aging as a root cause of hair thinning could further support and maintain a healthy hair growth cycle.

An important emerging mechanism in skin and hair aging is the formation of AGEs in collagen- spontaneous bonds between circulating sugar molecules and proteins that disrupt the tight mechanical helix of the collagen molecule. Chlorogenic acid found in citrus flowers (honeysuckle and sunflower) has been shown to inhibit the formation of AGEs, thereby maintaining the integrity of the collagen matrix.40,41

Hair follicles replicate extremely fast, requiring extra energy. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) is an endogenous lipophilic compound and an essential component of mitochondrial energy metabolism. Supplementation with CoQ10 has shown to improve skin hydration and have anti-aging effects on hair.42,43 In addition, methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) is an organosulfur compound. It supplies sulfur, which is used to make cysteine, a major building block of keratin. It is found in small amounts in garlic, onion, legumes, seeds, nuts, milk, eggs. One study showed that supplementation with MSM improved hair and nail conditions.44

Finally, oxidative damage is well established as an important mechanism of aging in the hair and skin. Antioxidants are key to combatting this natural degradation by preventing circulating free radicals and thus limiting damage to the skin. Natural antioxidants include chlorogenic acid and CoQ10.41,42

However, hair loss and thinning are now well established as the result of multiple causative factors that include inflammation, oxidative damage, environmental assaults, aging, psycho-emotional stress, and hormonal imbalances that span beyond the previously studied and known factors like androgens and nutrition. Based on this current understanding of the pathogenesis of hair loss and thinning, a multi-modal solution seems warranted while therapies targeting only singular mechanisms or pathways may be less than ideal or result in sub-optimal efficacy. While supplements addressing one factor of hair loss and thinning, like nutrition, have been popular in the dermatologic community, a clinically studied standardized nutraceutical that is able to target multiple pathways tied to hair growth could be seen as an effective intervention. While this is more time consuming than selecting a “one size fits all” approach, knowing what to look for in a clinically effective supplement will lead to greater patient satisfaction as well as a more effective and successful outcome.

References

- B. Waqas, A. Wu, E. Yim and S. Lipner. A survey-based study of physician practices regarding biotin supplementation. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 Feb;33(1):573-574.

- J. M. Falotico and S. R. Lipner. Biotin beware: Perils of biotin supplementation: Response to: The epidemiology, impact, and diagnosis of micronutrient nutritional dermatoses. Part 2: B-complex vitamins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;e279-280.

- K. G. Bistas and P. Tadi. Biotin. in StatPearls, Treasure Island, StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

- F. Saleem and M. Soos. Biotin Deficiency. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board., Dietary Reference Intakes: Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline., Washington DC: National Academy Press, 1998.

- R. Katta and E. L. Guo. Diet and hair loss: effects of nutrient deficiency and supplement use. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7(1):1.

- H. M. Said. Intestinal absorption of water-soluble vitamins in health and disease. Biochemical Journal. 2011;437(3):357-372.

- S. E. Aksac, S. G. Bilgili, G. O. Yavuz, et al. Evaluation of biophysical skin parameters and hair changes in patients with acne vulgaris treated with isotretinoin, and the effect of biotin use on these parameters. Int J Dermatol. 2021 Aug;60(8):980-985.

- W. B. Shelley and D. E. Shelley, Uncombable hair syndrome: Observations on response to biotin and occurrence in siblings with ectodermal dysplasia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985 Jul;13(1):97-102.

- J. Reilly, D. Cottrell, R. Martin and M. D. Cuddeford. Effect of supplementary dietary biotin on hoof growth and hoof growth rate in ponies: a controlled trial. Equine Vet J Suppl. 1998 Sep;(26):51-7.

- W. E. Contributors, “Hair Loss: The Science of Hair,” American Hair Loss Association, 01 March 2010. [Online]. Available: https://www.webmd.com/skin-problems-and-treatments/hair-loss/science-hair. [Accessed December 10, 2022].

- H. M. Almohanna, A. A. Ahmed, J. P. Tsatalis and A. Tosti. The Role of Vitamins and Minerals in Hair Loss: Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019 Mar;9(1):51-70.

- K. G. Thompson and K. Noori. Dietary Supplements in dermatology: A review of the evidence for zinc, biotin, vitamin D, nicotinamide, and Polypodium. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Apr;84(4):1042-1050.

- T. Soleymani, K. Lo Sicco and J. Shapiro. The Infatuation With Biotin Supplementation: Is There Truth Behind its Rising Popularity? A Comparitive Analysis of Clinical Efficacy Versus Social Popularity. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017 May 1;16(5):496-500.

- D. P. Patel, S. M. Swink and L. Castelo-Soccio, “A Review of the Use of Biotin for Hair Loss,” Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3(3):166-169.

- R. M. Trueb. Serum Biotin Levels in Women Complaining of Hair Loss. Int J Trichology. 2016;8(2):73-77.

- H. A. Miot and J. V. Schmitt. Efficacy of 2.5 mg oral biotin versus 5% topical minoxidil in increasing nail growth rate. Experimental Dermatology. 2021;30:1322-1323.

- V. E. Colombo, F. Gerber, M. Bronhofer, and G. Floersheim. Treatment of brittle fingernails and onychoschizia with biotin: Scanning electron microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6):1127-1132.

- FDA, “UPDATE: The FDA Warns that Biotin May Interfere with Lab Tests: FDA Safety Communication,” FDA, 2019.

- FDA, “The FDA Warns that Biotin May Interfere with Lab Tests: FDA Safety Communication,” FDA, 2017.

- M. K. H. G. Setty. Biotin Interference in HIV Immunoassays. in 2022 Advancing HIV, STI and Viral Hepatitis Testing Conference, 2022.

- D. Li, A. Ferguson, M. A. Cervinski, K. L. Lynch and P. B. Kyle, “AACC Guidance Document on Biotin Interference in Laboratory Tests,” 13 Jan 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.aacc.org/science-and-research/aacc-academy-guidance/biotin-interference-in-laboratory-tests. [Accessed Nov 2022].

- P. Grimsey, N. Frey, G. Bendig, J. Zitzler, O. Lorenz, D. Kasapic, and C. E. Zaugg. Population pharmacokinetics of exogenous biotin and the relationship between biotin serum levels and in vitro immunoassay interference. Int J Pharmacokinet. 2017;2(4):247-256.

- G. Ablon and S. Kogan. A Six-Month, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Safety and Efficacy of a Nutraceutical Supplement for Promoting Hair Growth in Women With Self-Perceived Thinning Hair. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(5):558-565.

- S. N. Deshmukh, A. M. Dive, R. Moharil and P. Munde. Enigmatic insight into collagen. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2016;(20):276-83.

- P. M. Campos, M. O. Melo, L. S. Calixto and M. M. Fossa. An Oral Supplementation Based on Hydrolyzed Collagen and Vitamins Improves Skin Elasticity and Dermis Echogenicity: A Clinical Placebo-Controlled Study. Clinical Pharmacology & Biopharmaceutics. 2015;4(3):142.

- A. Gautieri, A. Redaelli, M. J. Buehler and S. Vesentini. Age- and diabetes-related nonenzymatic crosslinks in collagen fibrils: Candidate amino acids involved in Advanced Glycation End-products. Matrix Biology. 2014;34:89-95.

- L. Baumann. Skin ageing and its treatment. Journal of Pathology. 2007;211:241-251.

- M. K. Dick, J. H. Miao and F. Limaiem, Histology, Fibroblast., Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

- S. Shuster, M. M. Black and E. McVitie. The influence of age and sex on skin thickness, skin collagen, and density. Br J Dermatol. 1975 Dec;93(6):639-43.

- W. Liu, H. Ma, L. Frost, T. Yuan, J. A. Dain and N. P. Seeram. Pomegranate Phenolics inhibit formation of advanced glycation endproducts by scavenging reactive carbonyl species. Food Funct. 2014 Nov;5(11):2996-3004.

- E. A. Mohamad, A. A. Aly, A. A. Khalaf, et al. Mousa. Evaluation of Natural Bioactive-Derived Punicalagin Niosomes in Skin-Aging Processes Accelerated by Oxidant and Ultraviolet Radiation. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021 Jul 17;15:3151-3162.

- M. Miyata, C. Mifude, T. Matsui, et al. Advanced glycation end-products inhibit mesenchymal-epidermal interaction by up-regulating proinflammatory cytokines in hair follicles. Eur J Dermatol. 2015 Jul-Aug;25(4):359-61.

- S. Oesser. The oral intake of specific Bioactive Collagen Peptides has a positive effect on hair thickness. Nutrafoods. 2020;1:134-138.

- J. Asserin, E. Lati, T. Shioya and J. Prawitt. The effect of oral collagen peptide supplementation on skin moisture and the dermal collagen network: evidence from an ex-vivo model and randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015 Dec;14(4):291-301.

- M. Yazaki, Y. Ito, M. Yamada, et al. Oral Ingestion of Collagen Hydrolysate Leads to the Transportation of Highly Concentrated Gly-Pro-Hyp and Its Hydrolyzed Form of Pro-Hyp into the Bloodstream and Skin. J Agric Food Chem. 2017 Mar 22;65(11):2315-2322.

- A. Leon-Lopez, A. Morales-Penaloza, V. M. Martínez-Juárez, A. Vargas-Torres, D. I. Zeugolis and G. Aguirre-Alvarez. Hydrolyzed Collagen-Sources and Applications. Molecules. 2019;24:22.

- F. D. Choi, C. T. Sung, M. L. Juhasz and N. A. Mesinkovska. Oral Collagen Supplementation: A Systematic Review of Dermatological Applications. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Jan 1;18(1):9-16.

- R. B. de Miranda, P. Weimer and R. C. Rossi. Effects of hydrolyzed collagen supplementation on skin aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2021 Dec;60(12):1449-1461.

- Z. Sun, J. Chen, J. Ma, Y. Jiang, M. Wang, G. Ren and F. Chen. Cynarin-Rich Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) Sprouts Possess Both Antiglycative and Antioxidant Activities. J Agric Food Chem. 2012 Mar 28;60(12):3260-5.

- J. Kim, I.-H. Jeong, C.-S. Kim, et al. Chlorogenic Acid Inhibits the Formation of Advanced Glycation End Products and Associated Protein Cross-linking. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34(3):495-500.

- K. Zmitek, T. Pogacnik, L. Mervic, J. Zmitek and P. Igor. The effect of dietary intake of coenzyme Q10 on skin parameters and condition: Results of a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. BioFactors. 2017;43:132-140.

- M. Giesen, T. Welß, E. Zur Wiesche, V. Scheunemann, S. Gruedl, Y. Oezkabakcioglu, E. Poppe and D. Petersohn. Coenzyme Q10 has anti-aging effects on human hair. International Journal of Cosmetic Science. 2009;31:154-155.

- N. Muizzuddin and R. Benjamin. Beneficial Effects of a Sulfur-Containing Supplement on Hair and Nail Condition: A prospective, double-blind study in middle-aged women. Natural Medicine Journal. 2019;11:11.