J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(2):44–48.

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(2):44–48.

by Khaled Gharib, MD and Hala M. Morsi, MD

All authors are with the Dermatology Department, Faculty of Medicine at Zagazig University in Zagzig, Egypt.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Melasma is a relatively common, acquired facial skin disorder of hyperpigmentation. Though it occurs in both sexes, nearly 90% of patients are female. It manifests as hyperpigmented macules and patches distributed symmetrically on the face, neck, and, rarely, the upper limbs.

Objective. The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the clinical efficacy and adverse effects of intralesional injection of tranexamic acid (TA) versus cryotherapy in the treatment of melasma.

Methods. Patients were divded into two groups: Group A and Goup B. Group A comprised 28 patients aged 27 to 50 years. They received localized intralesional injections of TA. According to Wood’s light examination, patients were divided into two subtypes; 13 patients with mainly dermal-type melasma and 15 patients with mainly mixed-type melasma. Family history was obtained in 12 patients. Group B comprised 28 patients aged 29 to 46 years were included. They were treated with cryotherapy. According to Wood’s light examination, the patients were divided into two subtypes of melasma; 8 patients with mainly dermal-type melasma and 10 patients with mainly mixed-type melasma.

Results. There were no statistically significant differences between Group A and Group B according to contraception, sun exposure, and family history. There was a statistically significant difference between Group A and Group B according to previous treatment. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups according to drug allergy. There were no statistically significant differences according to systemic disease or general examination.

Conclusion. Intralesional tranexamic acid is a safe and effective method for the treatment of melasma with no risk of PIH, thrombosis, or bleeding; however, more sessions with longer follow-up periods are recommended, as the final response may take several months to occur. Cryotherapy was neither safe nor effective due to the risk of PIH.

Keywords: Melasma, hyperpigmentation, tranexamic acid, cryotherapy

Melasma is a relatively common, acquired facial skin disorder of hyperpigmentation. Though it occurs in both sexes, nearly 90% of the patients are female.1 It manifests as hyperpigmented macules and patches distributed symmetrically on the face, neck, and, in rare instances, the upper limbs.2

The role of tranexamic acid (TA) in the treatment of melasma was first shown in 1979. Sadako3 tried to use TA to treat a patient with chronic urticaria. Incidentally, he found that the melasma severity of that patient was significantly reduced after 2 to 3 weeks.

The mechanism of cryotherapy in the treatment of melasma is that discolored skin cells become damaged when they thaw after freezing. Liquid nitrogen is applied to the affected skin, and then heat transfers from the skin to the nitrogen, causing it to boil and evaporate. Once skin cells have been frozen with liquid nitrogen, they begin to thaw very slowly, causing water and ice to cross through the cell membranes and damage the cells. The cells then die causing inflammation. This process removes the discolored cells, allowing new cells to grow in their place.4

The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the clinical efficacy and adverse effects of intralesional injection of tranexamic acid versus cryotherapy in the treatment of melasma.

Methods

This study was carried out at the outpatient clinics of the Dermatology, Venereology, and Andrology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University Hospitals from October 2018 until October 2019. Fifty-six patients with melasma aged 27 to 50 years were enrolled in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Zagazig University. An informed consent was taken from each patient.

Inclusion criteria

- Age above 18 years

- Moderate-to-severe melasma with a malar distribution

- Patient with mixed- or dermal-type melasma

Exclusion criteria

- Pregnant or nursing women

- Women taking contraceptive pills at the time of the study or in the prior 12 months

- Any known bleeding disorders or the concomitant use of anticoagulants

- Women on any concurrent therapy for melasma

- Patients who were using any topical therapy for melasma, including hydroquinone, up to one month prior to enrollment

Participants. Participants were randomly divided into two groups. Group A included 28 patients aged 27 to 50 years. They received localized intralesional injections of TA. According to Wood’s light examination, patients were divided into two subtypes; 13 patients with mainly dermal-type melasma and 15 patients with mainly mixed-type melasma. Family history was obtained from 12 patients.

Group B included twenty-eight patients aged 29 to 46 years. They were treated by cryotherapy. According to Wood’s light examination, the patients were divided into two subtypes of melasma; eight patients with mainly dermal-type melasma and 10 patients with mainly mixed-type melasma. A family history was obtained from 18 patients.

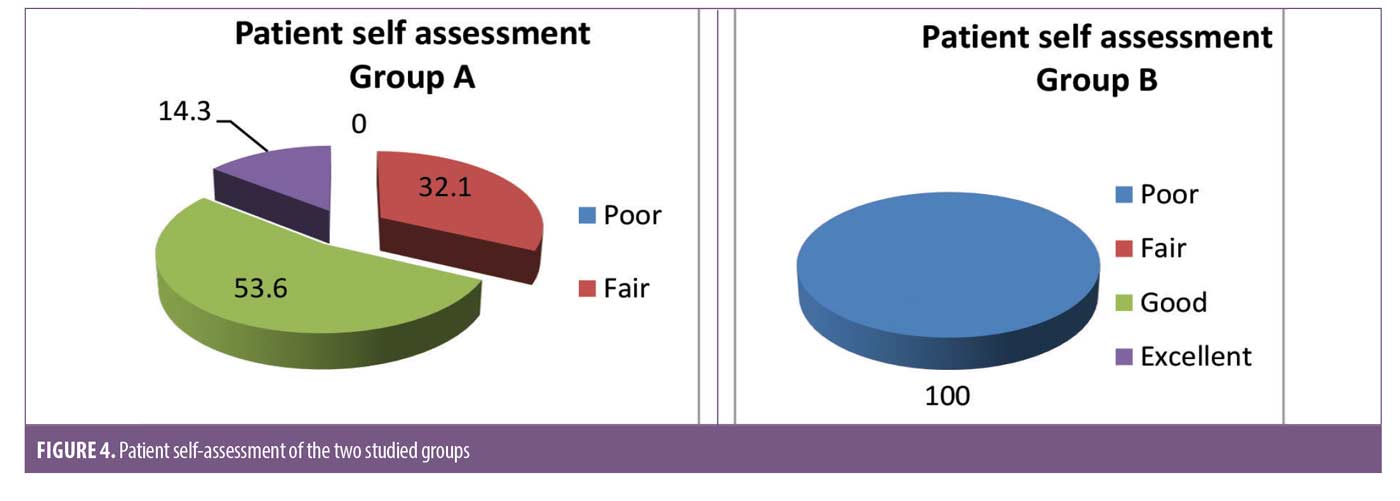

Patient satisfaction. A questionnaire was given to patients at the end of treatment to assess their degree of improvement. The patient’s self-assessment was graded along four scales of pigmentation lightening: more than 75% lightening (excellent); 51 to 75% (good); 26 to 50% (fair); and 0 to 25% (poor).

Side effects. Any side effects observed, such as pain, post procedure erythema, or edema, were recorded at each session. For the cryotherapy group, hyperpigmentation was also recorded.

Results

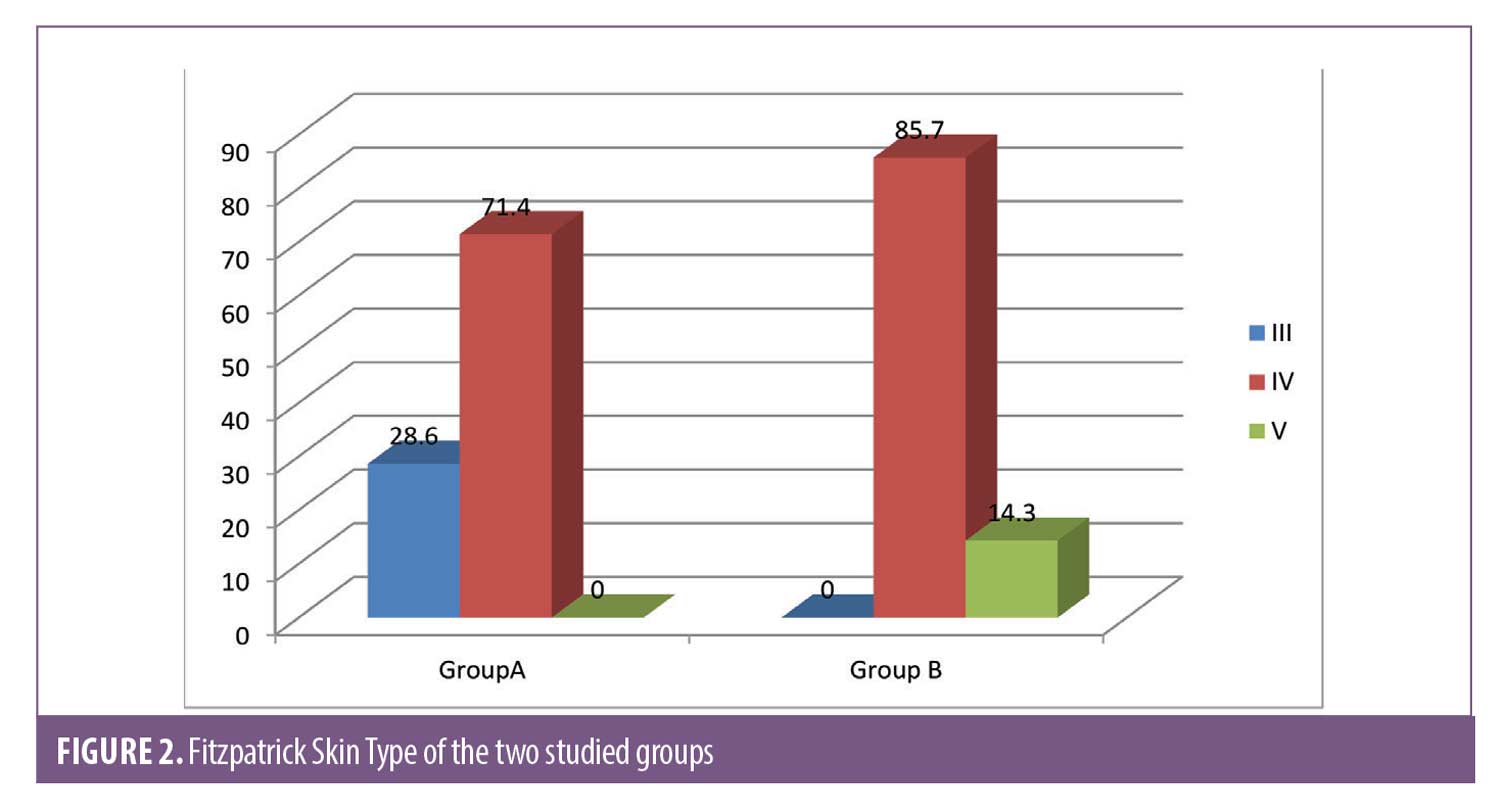

Group A (intralesional injection of tranexamic acid). This group included 28 female patients, and their ages ranged from 27 to 50 years with a mean of 37.71 ± 5.15. Eight patients had skin phototype III (28.6%), and 20 patients had phototype IV (71.4%).

The duration of melasma ranged from 1 to 16 years with a mean of 4.5 ± 3.8. According to Wood’s light examination, 13 patients (46.4%) had dermal-type melasma and 15 patients (53.6%) had mixed-type melasma. Family history was obtained from 16 patients (57.1%).

Group B (cryotherapy). This group included 28 female patients aged 29 to 46 years with a mean age of 39.36 ± 7.62. Twenty-four patients had skin phototype IV (85.7%), and four patients had phototype V (14.3%).

The duration of melasma ranged from 1 to 20 years with a mean of 6.93 ± 6.32. According to Wood’s light examination, 18 patients (64.3) had dermal-type melasma and 10 patients (35.7%) had mixed-type melasma. Family history was obtained from 10 patients (35.7%).

The demographic data of the two groups showed a statistically significant difference between Group A and Group B in age. There was no statistically significant difference between Group A and Group B in occupation (Table 1).

There were no statistically significant differences between Group A and Group B with regards to contraception use, sun exposure, and family history (Table 2).

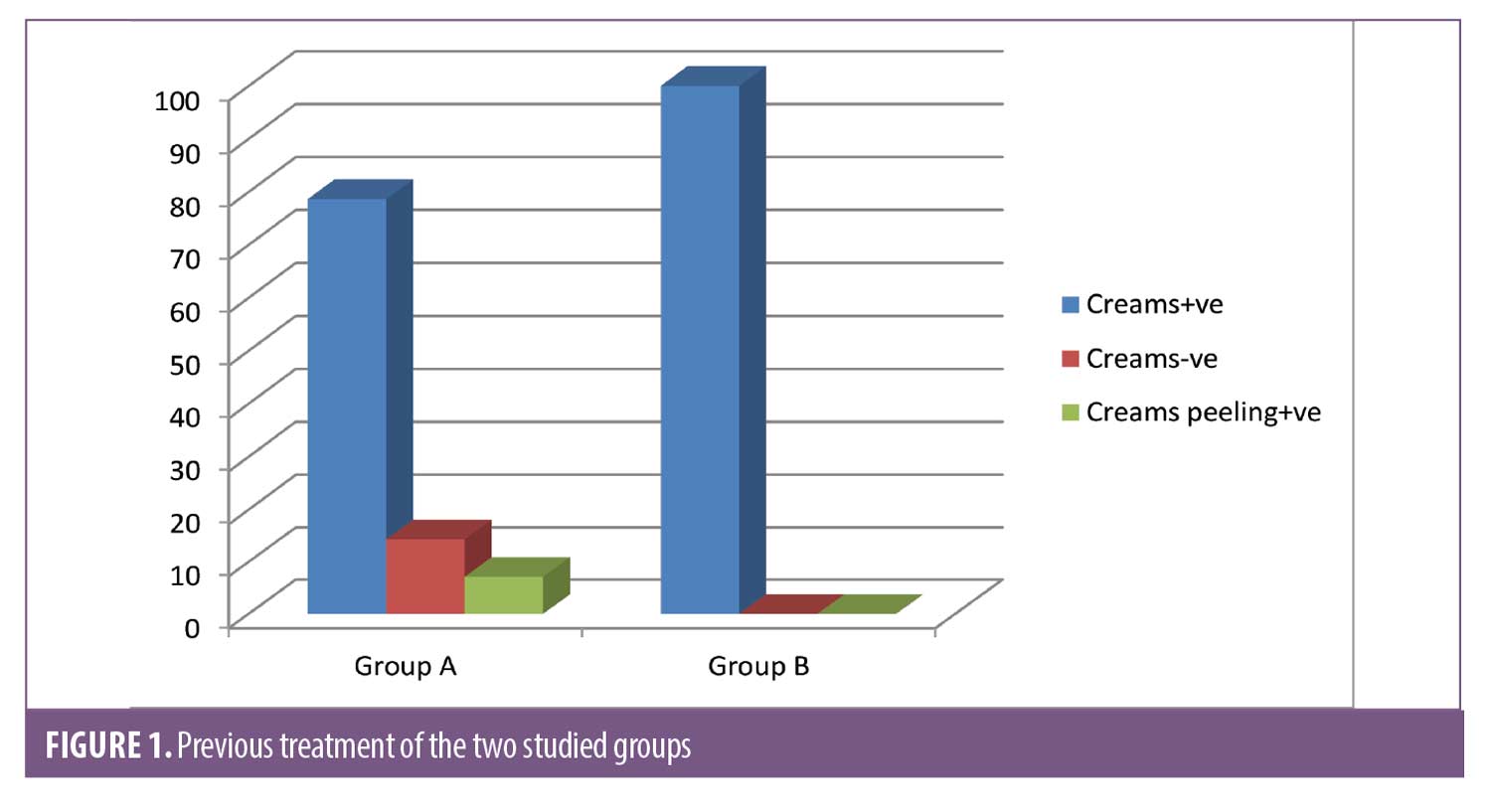

There was a statistically significant difference between Group A and Group B according to previous treatment. There was no statistically significant difference with regards to drug allergies (Figure 1). There were no statistically significant differences according to systemic disease or general examination (Table 3).

There was a statistically significant difference between Group A and Group B according to Fitzpatrick skin type. There were no statistically significant differences in the duration or type of melasma (Figure 2).

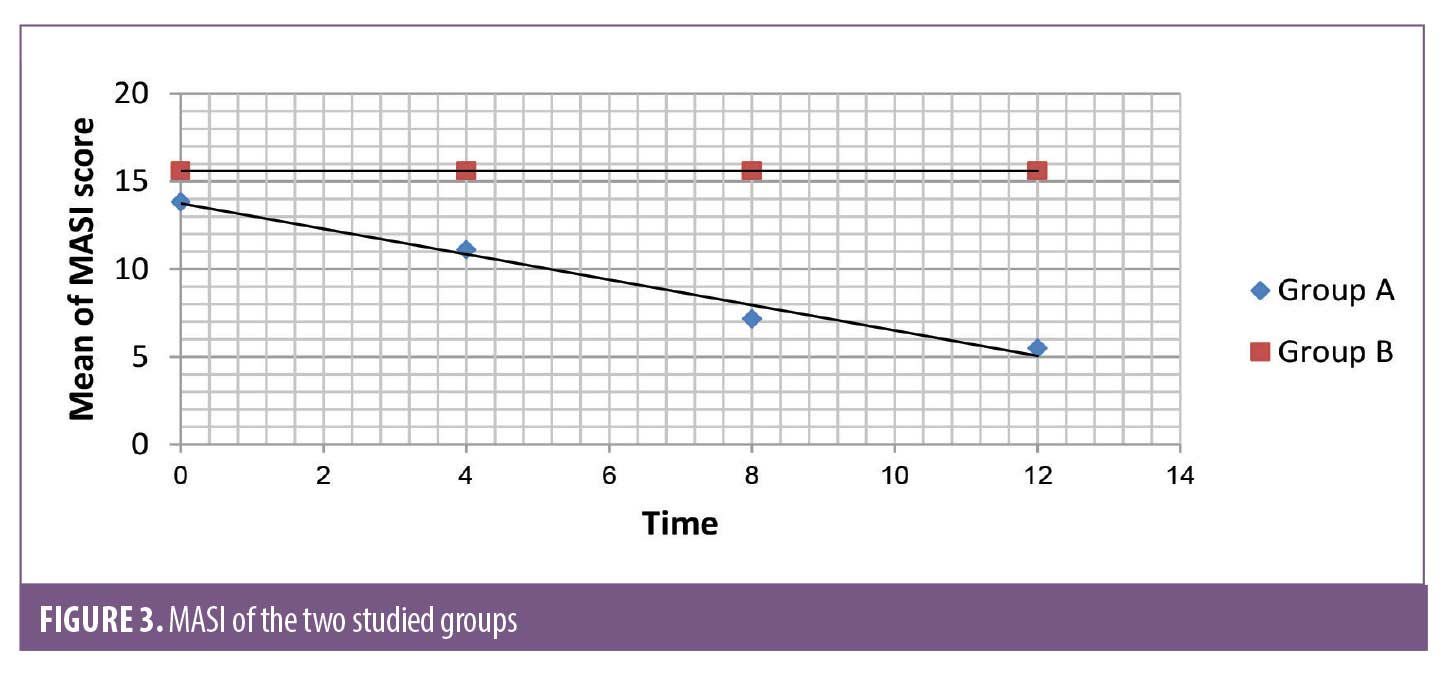

The response to treatment was assessed using the Melasma Area Severity Index (MASI) scoring system before and after treatment. There was a statistically significant difference between the MASI scores before and after treatment in Group A, but there was no statistically significant difference in the MASI scores before and after treatment in Group B. There were statistically significant differences in the MASI scores between Group A and Group B at 4 and 12 weeks of treatment (Figure 3).

There was a statistically significant difference between Group A and Group B in patient self-assessment (Figure 4). There was no statistically significant difference in Group A between MASI and patient self-assessment at 12 weeks (Table 4) or clinical cases (Figures 5 and 6).

Discussion

Melasma manifests as symmetrical and irregular tan-brown macules on the face. Though predominantly seen on the malar areas of cheek, it may also appear on the forehead and chin. Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, genetic susceptibility, and hormonal imbalance are considered to be aetiological factors. Although no race is spared, melasma is far more common in women and in dark skinned individuals. It is a common and growing cosmetic concern among populations with dark skin types.5,6

Clinical trials have shown that topical medications demonstrate some efficacy in treating the epidermal-type melasma, but not in the dermal or mixed types. Prolonged application, slow response, limited effects, and undesirable recurrence are the major disadvantages of topical therapies causing patients to abandon treatment. In addition, topical bleaching agents may irritate the skin and develop PIH or result in exogenous ochronosis. Phototherapy is a good method; however, the rate of melasma recurrence remains disappointingly high. The most effective and safe treatment for melasma has yet to be determined.7

With the increased evidence showing the interaction between keratinocytes and melanocytes in the process of melanogenesis through the PA activation system, there are many reasons and rationales to justify adding TA, a PA inhibitor, as an adjuvant in the treatment of melasma to improve the efficacy of known effective treatments and reduce the chance of recurrence.3

The present study revealed promising results regarding the use of intradermal injection of TA. The severity of melasma was reduced after treatment with intradermal injection of TA in many patients in Group A. The difference in the MASI score in this study before and after treatment with intradermal injection of TA was statistically significant (p<0.001). The mean MASI score after treatment decreased from 13.83±7.23 at baseline to 11.11±5.48, 7.17±3.9, and 5.49±3.91 at 4, 8, and 12 weeks, respectively. The patient self-assessment of melasma improvement was evaluated at Week 12; 9, 15, and 4 patients (32.1%, 53.6%, and 14.3, respectively) graded their improvement as fair (26-50%), good (51-75% lightening) and excellent (>75% lightening), respectively.

The results of this study were close to those of the study of Lee et al,8 who used TA (4 mg/mL) intradermal injection to treat melasma. The study stated that TA intradermal injection was effective with high patient satisfaction and no increase in the frequency of complications [9.4% as good improvement (51–75% lightening), 76.5% as fair (26–50% lightening) and 14.1% as poor (0–25% lightening)]. The study by Lee et al8 showed results that were less promising than those obtained in the present study. Side effects were transient and well tolerated in both studies.

A prospective, randomized, open-label study comparing TA (4 mg/mL) microinjections with TA microneedling was performed by Budamakuntla et al.9 It showed 26.09% good, 47.82% moderate, and 26.09% mild response in the microinjection group compared with 6.90% very good, 34.48% good, 34.48% moderate and 24.14% mild response in the TA microneedling group. Localized burning and erythema were noticed in a few patients despite using topical EMLA cream. The results of the microinjection group were close to our results, but localized burning and erythema were noticed in all patients in Group A.

All patients in this group showed erythema and edema in the injection sites that were transient and completely resolved within two days in all patients. This side effect was also found by Budamakuntla et al.9

There were no major adverse effects observed in study Group A, such as persistent PIH, persistent erythema, or thrombotic or bleeding tendency.

The definite number of sessions or the definite period between treatment sessions varied in the intradermal injection group in different studies. This study followed a protocol of 12 sessions with a one-week interval between sessions, while other studies preferred to choose a four-week interval period.

Patients were followed up at Week 24 to assess the maintenance of improvement. In six patients, the pigments gradually reappeared; however, repigmentation was still less than initial hyperpigmentation, possibly because repigmentation was induced by persistent trigger factors such as sun exposure. Partial repigmentation indicates that additional treatment sessions or therapeutic options may be required for maintenance therapy.

In Group B the result was not significant (P=1). There was no decrease in MASI at the end of the 12-week follow-up, and the patient self-assessment was poor. Many patients in Group B complained of pain at the time of treatment and shortly thereafter. Swelling and redness were found in all patients after the procedure and for 2 to 3 days. Post inflammatory hyperpigmentation was recorded in four patients.

Conclusion

Intralesional tranexamic acid is a safe and effective method for the treatment of melasma with no risk of PIH, thrombotic or bleeding tendency; however, more sessions with longer follow-up periods are recommended, as the final response may take several months to occur. Cryotherapy was neither safe nor effective due to the risk of PIH.

References

- Ebrahim HM, Said Abdelshafy A, Khattab F, Gharib K. Tranexamic Acid for Melasma Treatment: A Split-Face Study. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46 (11): 102–107.

- Arefiev B and Hantash M: Advances in the Treatment of Melasma: A Review of the Recent Literature. Dermatol Surg. 2012; 38:971–984.

- Tse, Tsz Wah, and Edith Hui: Tranexamic acid: An important adjuvant in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013; 12.1: 57–66.

- Morgan AJ and Elston DM (2012): Cryotherapy. http:\\ emedicine. medscape.com/article/1125851-overview.

- Anstey V . Disorders of Skin Color. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Wiley-Blackwell. 2010; p. 58.34.

- Abou-Taleb DA, Ibrahim AK, Youssef EM, Moubasher AE. Reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change over time of the modified Melasma Area and Severity Index score. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:210–7

- Karn D, KC S, Amatya A, Razouria A et al.. Oal Tranexamic Acid for the Treatment of Melasma. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2012; 10(4):40-43.

- Lee JH, Park JG, Lim SH, et al. Localized intradermal microinjection of tranexamic acid for treatment of melasma in Asian patients: A preliminary clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006; 32:626-31.

- Budamakuntla, Leelavathy et al. A randomised, open-label, comparative study of tranexamic acid microinjections and tranexamic acid with microneedling in patients with melasma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6.3 :139.