J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(11):37–43

J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(11):37–43

by Zoya Diwan, MBBS, BSc, PG Dip Clinical Dermatology; Sanjay Trikha, MBBS, BSc; Sepideh Etemad-Shahidi, BDS, BSc, RCS Eng; Surbhi Virmani, MBBS, MD, PG Dip Dermatology, GDL, LPC, LLB; Catherine Denning, MBBS, MRCS, BSc; Yusra Al-Mukhtar, BDS, BSc, MFDS, RCS Ed, MJDF RCS Eng; Christopher Rennie, MBBCh, MRCS; Amanda Penny, MBBS, BSc, FRCA; Yalda Jamali, MBChB; and Nina Cassandra Edwards Parrish, BSc

Dr. Diwan is President of Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and the medical director of Trikwan Aesthetics in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Trikha is Vice President of Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and the director of Trikwan Aesthetics in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Etemad-Shahidi is a member at Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and a practitioner at Medicetics in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Virmani is a member of Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and is with Cosderm in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Denning is a member of Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and a director of Clinic 1.6 in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Al-Mukhtar is a member of Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and a director at Dr. Yusra Clinic in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Rennie is a member of Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and a director at Romsey Medical Aesthetics in Winchester, United Kingdom. Dr. Penny is a member of Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and a doctor at Courthouse Clinics in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Jamali is a member of Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and a clinic education fellow at Harley Academy in London, United Kingdom. Dr. Parrish is a member of the Academic Aesthetics Mastermind Group and Trikwan Aesthetics in London, United Kingdom.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this study.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: With the number of aesthetic soft tissue filler treatments rapidly increasing, we have witnessed an increase in complications associated with such treatments. While rare, abscesses can arise as a result of these treatments, and current detailed guidelines do not exist detailing exactly how to manage them.

Objective. Our aim was to develop evidence-based and experience-based guidelines on how to, specifically, manage abscesses secondary to hyaluronic acid dermal fillers.

Methods. A thorough MEDLINE literature search of keywords, including abscess, abscess management/treatment, hyaluronic acid, dermal fillers, and soft tissue fillers, was completed to collect specific cases of abscesses secondary to soft tissue filler. Inclusion criteria involved papers published from 2010 to 2020 that focused specifically on soft tissue fillers in the face. In addition, we looked at papers that discussed abscesses secondary to soft tissue fillers in general and their management. We also reported three cases of abscesses secondary to hyaluronic acid dermal fillers that have been described by three different practitioners, detailing their history, examination, management, and outcomes. Experience and evidence have been collated to produce management guidelines.

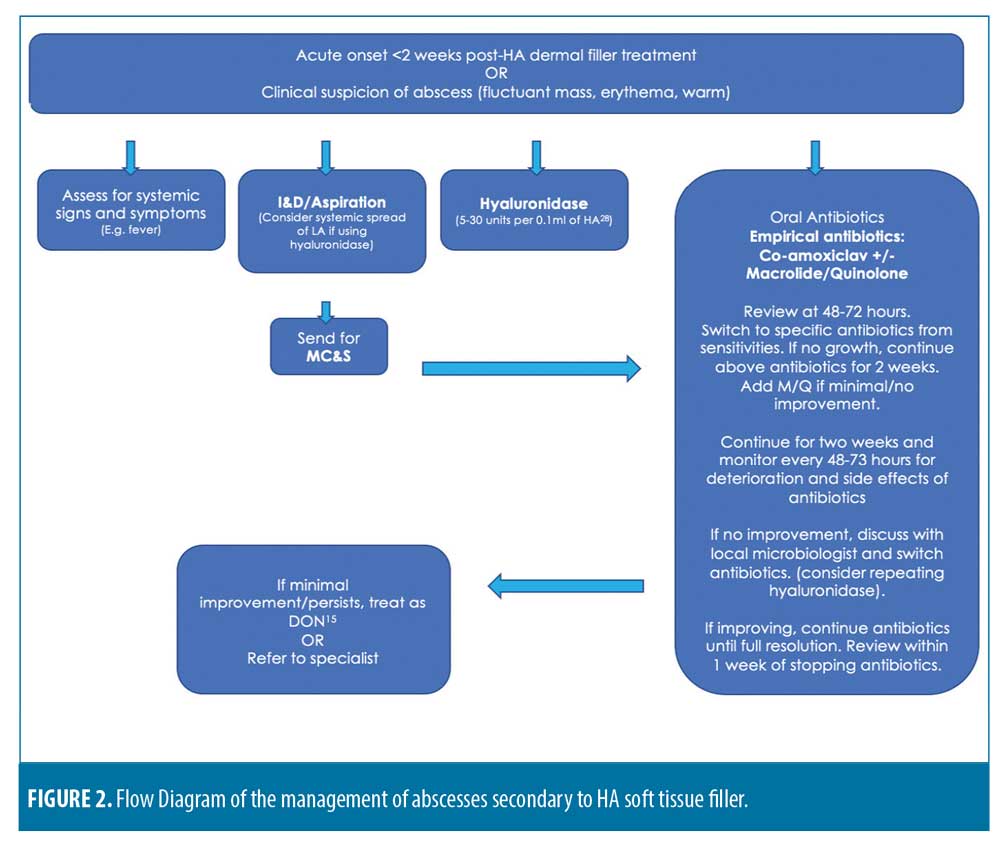

Results and Conclusion. It is clear that each case is unique, but there is no current universal consensus on the risk assessment before treatment nor general management of abscesses secondary to soft tissue filler. The majority of the reports and cases discussed in the paper suggested the use of co-amoxiclav along with a macrolide or quinolone for at least two weeks. Incision and drainage are universally accepted as gold standard management. Microbiology, sensitivities, and cultures are also recommended. Hyaluronidase use, while controversial, is encouraged in effectively managing abscesses secondary to hyaluronic acid dermal filler.

KEYWORDS: Hyaluronic acid, abscess, complications, cosmetic complications management, management guidelines, dermal filler complications

With the number of aesthetic soft tissue filler treatments rapidly increasing, we have witnessed an increase in the complications associated with such treatments. While rare, abscesses can arise as a result of these treatments, and current guidelines detailing exactly how to manage them do not exist. Abscess is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “a swollen area within body tissue, containing an accumulation of pus.” We reviewed the current literature on managing abscesses resulting after soft tissue filler injection. We also detailed the history and management of three cases of abscesses secondary to hyaluronic acid dermal filler. Finally, a proposal of new guidelines on how these should be managed in the future is put forth.

General cutaneous abscesses are defined as painful collections of exudates under the skin that formed as a result of an infection, often due to a bacterial source.1 In terms of treatment options, the National Health Service (NHS) has advised a case-by-case approach, including the use of antibiotics, drainage, debridement, and, if severe enough, surgery, as well as allowing for full natural resolution. The treatment approach depends on the location and severity of the abscess.1 The Rapid Recommendations Team at the British Medical Journal (BMJ) reviewed current guidelines in Infectious Disease Society of America, Evidence Based Medicine, and Nederlands Huisarten Genootschap, all of which suggested that antibiotics should not be used in conjunction with incision and drainage (I&D) in uncomplicated cutaneous abscesses.2–5

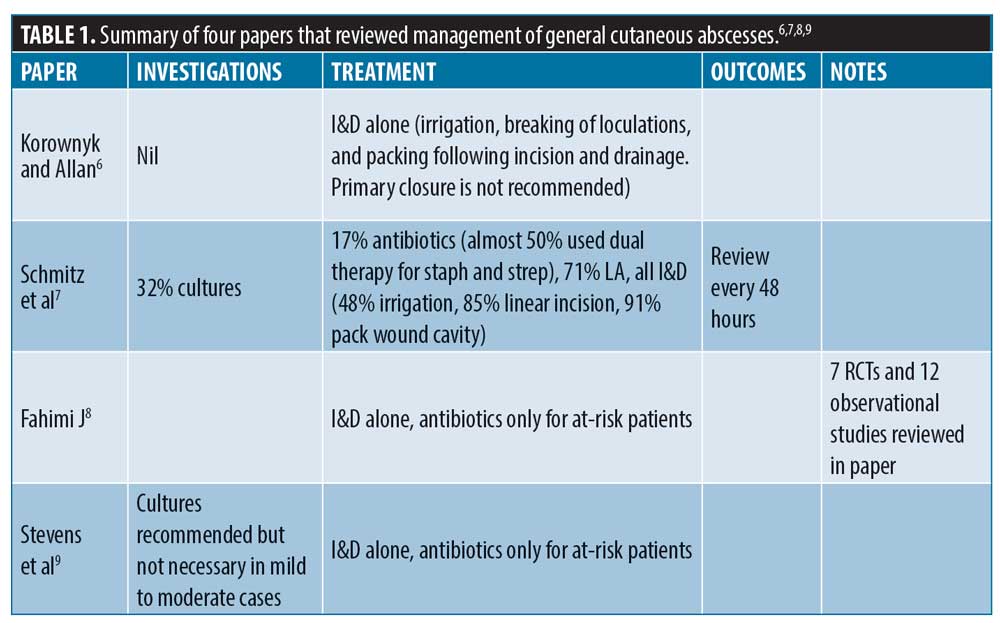

There are numerous papers that review the management of general cutaneous abscesses; Table 1 summarizes some of these. One of these papers, from Korownyk et al, reviewed multiple studies and developed evidence-based guidelines for managing cutaneous abscesses. They concluded that in patients with no immunocompromising factors, I&D alone was sufficient, with no evidence to support the use of additional antibiotics, swabbing, or cultures.

Similarly, Schmitz et al7 reviewed the experience of 350 doctors in an American emergency department and found that all of these doctors (100%) recommended I&D for simple cutaneous abscesses. They also found that only 32 percent of these doctors would send cultures, and 17 percent prescribed antibiotics routinely. However, over two-thirds recommended antibiotics in addition to I&D if the patient was immunocompromised. Almost 50 percent irrigated after drainage, 91 percent packed the wound, and a majority of the doctors utilized linear incision during the I&D procedure.7

The Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) reviewed multiple randomized controlled studies in a meta-analysis and found no benefit of using antibiotics in addition to I&D for simple cutaneous abscesses, noting that these should only be used for complicated patients.8,9 They also discussed the difficulty in a “uniform” management plan for all patients with cutaneous abscesses, as they are a group with varying severities and risk factors.8 Due to potential harm of antibiotic overuse, they recommended limiting antibiotic prescription to certain cases, including patients with cellulitis, immunosuppression, and fever.8,9

Similarly, a review from List et al10 reviewed three randomized controlled studies and an observational study that took place over a 10-year period. Based on their review, the authors concluded that there is not enough evidence in the literature to support or oppose the use of antibiotics or wound packing as an adjunct to I&D in cutaneous abscesses.10

Currently, NHS guidelines on general cutaneous abscesses depends on the size of the abscess. Smaller abscesses might drain naturally or require a course of antibiotics. Larger cutaneous abscesses will need I&D or even surgery.11 The British Medical Journal (BMJ) recommendations included using trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for cutaneous abscesses rather than I&D alone in general but emphasized the consequences of antimicrobial resistance versus the benefits of antibiotics, which might be minimal, as an adjunct to I&D; risk versus benefit needs to be considered for each patient.12

Methodology

In this paper, we aimed to develop evidence-based and experience-based guidelines on how to manage abscesses secondary to hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. A thorough MEDLINE literature search of keywords, including abscess, abscess management/treatment, hyaluronic acid, dermal fillers, and soft tissue fillers, was completed to collect specific cases of abscesses secondary to soft tissue filler. Inclusion criteria involved papers published from 2010 to 2020 which focused on soft tissue fillers in the face. In addition, we looked at papers on the management of abscesses secondary to soft tissue fillers in general. We also report three cases of abscesses secondary to hyaluronic acid dermal fillers, detailing their history, examination, management, and outcomes.

Case Series

Case 1. A 57-year-old female patient had multiple hyaluronic acid filler treatments, including in the nasolabial folds (NLF). Juvederm Volift (Allergan Inc.; Irvine, California) was used with 0.5mL injected into each NLF using a 25G cannula. Injections were carried out by a doctor in an aesthetic clinic. Twelve days posttreatment, the patient noticed a red, painful lump in her right NLF region and went to the NHS Emergency Department. The patient was prescribed 500mg of flucloxacillin to be taken orally four times per day for seven days. She was then examined in the original aesthetic clinic, whereupon a 2.5cm by 1.5cm palpable abscess with overlying erythema, which was tender and warm to the touch, was observed. Aspiration of 1mL pus/exudate was performed but not sent for cultures. One hundred units of hyaluronidase were injected into the area, flucloxacillin was continued for a total of seven days, and clarithromycin was added for a total of 10 days. At follow up 48 hours later, an additional 50 units of hyaluronidase were injected.

The patient had full resolution once the course of antibiotics was complete; however, the abscess recurred nine days after stopping the antibiotics. During this period, the patient was abroad and attended the local emergency department, where incision and drainage was performed, cultures and sensitivities were sent, and she was prescribed five days of azithromycin 250mg once daily orally and co-amoxiclav 500/125mg three times per day. She was examined in the United Kingdom by the original aesthetic doctor, where she was continued on co-amoxiclav for a total of 18 days, as cultures returned negative with full resolution. The patient suffered no further recurrences and no scarring. Regarding the patient’s risk factors, she had previously received filler in the same region and was a smoker. Figure 1 shows a timeline of photographs showcasing the abscess, its recurrence, and resolution.

Case 2. A 46-year-old female patient was seen on a dermal filler training day, where Juvederm Voluma (Allergan Inc.; Irvine, California) was placed in multiple locations, including the patient’s left and right cheek and submalar regions. She was injected by delegates on a training course under the supervision of a cosmetic dentist.

The patient saw her NHS General Practitioner (GP) seven days after receiving the fillers, reporting tender swelling over her right cheek. Since the patient had a penicillin allergy, the GP prescribed erythromycin 500mg four times per day. At Day 10, she was seen in the cosmetic dentist’s clinic, whereupon a 1cm by 2cm area of nonfluctuant swelling was observed over her right cheek, just inferior to the orbital rim, which was tender and had mild overlying erythema. The patient was prescribed additional metronidazole, as she declined hyaluronidase. The patient developed another area of swelling over the left cheek, which, along with the first area of swelling, improved over two days.

Eighteen days after the initial filler procedure, the swelling recurred in the right and left cheeks while she was away on a trip. The patient was refused to be seen by a plastics team, so further treatment was temporarily delayed. Instead, the patient went to an alternative hospital the next day and had an incision and drainage with clindamycin 500mg once daily prescribed.

Two months after the initial filler procedure, the swelling recurred a third time at the right zygoma and left submalar region. Hyaluronidase was used this time (150 units initially, then a further 75 units 10 days later) and clindamycin and ciprofloxacin were started for eight weeks. The patient had no further recurrences and had a full resolution at four months. Regarding the patient’s risk factors, she had received filler in the same region multiple times over the previous eight years.

Case 3. A 55-year-old female patient was treated with hyaluronic acid soft tissue filler as part of a pharmaceutical demonstration on a training day. She received 2mL of Belotero volume (Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Frankfurt am; Main, Germany) using periosteal bolus technique with a needle in her right and left cheeks.

Six weeks later, she received a 0.3-mm microneedling treatment with no use of topicals immediately following the treatment. Two days later, the patient reported a red, tender area over her left cheek and was called in for review. Examination revealed a 3-cm area of erythema and induration that was tender to palpate over the zygomatic point between the medial and lateral zygoma. Presumed cellulitis was treated with seven days of co-amoxiclav.

Examination of the patient after antibiotic completion revealed a worsening of the area of induration, which increased in size to 5 to 7cm. The patient was then switched to a seven-day course of flucloxacillin. Ten days following the second course of antibiotics, the patient exhibited worsening erythema, exquisite tenderness, and induration spreading down to the jaw line and up to the periorbital region. At this time, there was a fluctuant mass measuring 2 to 3cm palpated along the zygomatic bone. She was given an additional five days of flucloxacillin and 3mL of pus/exudate was aspirated from the fluctuant mass. Seven days of flucloxacillin were also given to take at home. Aspirate was sent for cultures and sensitivities and discussed with a microbiologist, who found the sample to be sterile of pathogens. After completing the third week of antibiotics, an additional 0.3mL of pus/exudate was aspirated from the area of fluctuance, and the filler was dissolved using 1700 units of hyaluronidase and lidocaine. A pharmacist advised to treat as an oral abscess, to continue flucloxacillin, and add in metronidazole for two additional weeks. After two weeks of dual antibiotic therapy, there was no evidence of abscess, erythema, or induration, and the patient felt well.

Four weeks following complete resolution of any infection, the patient returned to the clinic, complaining of asymmetry following treatment. During the examination, it was clear that not only was there (expectedly) less volume following hyaluronidase treatment, but the skin overlying the defect was tethered to underlying structures. The patient insisted she would like more filler treatment to correct the asymmetry, so 2.4mL Belotero Volume was injected.

Three days following the second treatment with HA filler, the patient returned to clinic and saw a different doctor, reporting further swelling. The patient exhibited gross edema to the left cheek that extended to the periorbital region, along with some mild erythema that was warm to the touch when compared to the right side. The clinician restarted dual antibiotic therapy (14-day course of both flucloxacillin 500mg QDS and metronidazole 500mg TDS) as before with added oral steroids, and 40mg of prednisolone once a day for two days. A letter was sent to the GP to arrange urgent ultrasound imaging and maxillofacial outpatient review.

Unfortunately, the patient did not adhere to the antibiotics and solely took the steroids for three days. Over the weekend, the patient contacted the clinic and sent photos that showed her edema and erythema worsening. At this point, the patient was strongly advised to go to A&E urgently for ophthalmic examination and plastic surgical specialist review. When the patient was admitted, plastic surgeons performed a surgical incision and drainage, resuming antibiotic therapy with gentamycin.The patient was then lost to follow-up.

Discussion

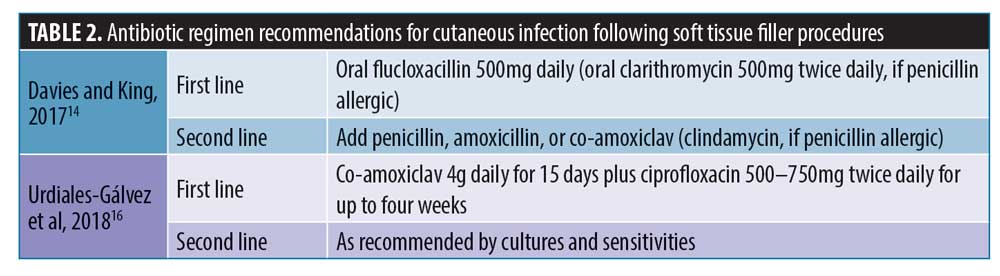

Overview of the management of filler-related abscesses as found in available literature. Abscesses following filler procedures are most typically acute infections occurring within two weeks after treatment. These are mainly caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.13 Less commonly, they can occur months or years after treatment. The Aesthetic Complications Expert (ACE) Group suggest I&D, photographic documentation, and review within 48 hours for abscesses secondary to soft tissue filler.14,15 For acute skin infections following filler procedures, including abscesses, they recommend a specific antibiotic regimen (Table 2).

Additionally, in 2018, an international consensus group completed a review to assess the management of complications after aesthetic treatments.16 They concluded that the first-line treatment for acute abscesses should be I&D, cultures, and sensitivities, cover with antibiotics until sensitivities are confirmed, and then commence specified antibiotics.16 The panel provided empirical antibiotic recommendations (Table 2). They advised caution with the use of hyaluronidase, as it could cause or worsen the spread of the infection to surrounding tissues.16

When abscesses following soft tissue filler treatment occur in a delayed fashion after two weeks and up to years after the initial treatment, they are likely due to biofilms.13 The ACE Group coined the term “delayed onset nodule” (DON), which they defined as “a visible or palpable unintended mass that occurs at or close to the injection site of dermal filler,” and all DONs will have some sort of underlying infective process.14,15,16 This includes abscesses, granulomas, and biofilms. The ACE Group provided detailed recommendations on the management of inflammatory DONs, which included using macrolide and tetracycline or quinolone antibiotics for 4 to 8 weeks, then considering the use of hyaluronidase and intralesional steroids.14,15

A review from Kim et al17 suggested that singular abscesses are most likely caused by skin bacteria, while multiple abscesses are most likely due to syringe contamination.17 They provided their recommended guidelines on the management of abscesses secondary to soft tissue filler, and included the use of I&D, oral antibiotics, and careful use of hyaluronidase. Moreover, they cautioned against the use of hyaluronidase in cases of surrounding cellulitis and non-fluctuant abscesses.17 If the aforementioned methods fail to treat, then suspicions should point to a possible biofilm or other DON, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or non-typical tuberculosis.17

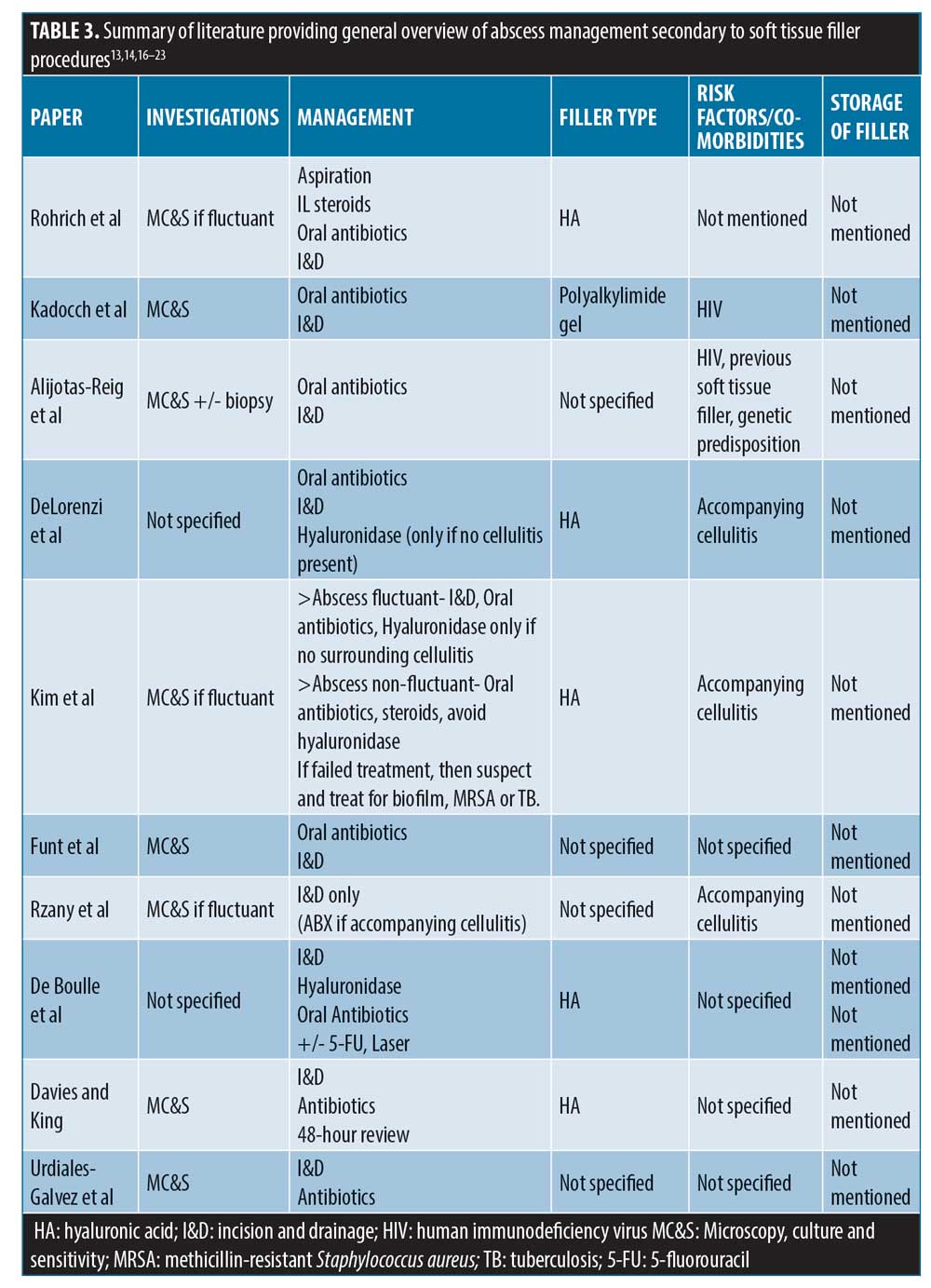

The overriding opinion in most published cases is that I&D should be the ultimate goal for treatment for abscess related to filler treatment; however, there is varying opinion on the use of hyaluronidase, antibiotics, and use of the investigations (summarized in Table 3).

Specific management of filler-related abscess cases as found in available literature. There have been few reported cases in the literature of abscesses secondary to soft tissue filler (summarized in Table 4); this article thus complements the limited number. It is interesting to note that there is no consistency in terms of management and outcomes. Seven out of the 10 cases described full resolution, but this can take up to 12 months in certain cases. Eight out of the 10 cases used antibiotics, and 7 out of 10 investigated with microbial cultures. Eight out of 10 also had I&D, and hyaluronidase was used in 5 out of 9 cases of HA filler abscess complication.

While some of these cases have developed outside of the acute phase window, they are likely due to biofilm; certain bacteria secrete an extracellular shield to surround them, protecting them from the immune system.15 These bacteria are stimulated by repeated trauma in that same region (i.e., repeat treatment injections at the same site) or systemic illness.15 When this occurs, abscesses as well as other DONs can arise.15

For example, Conrad et al26 described three separate cases where all patients were either over 50, had previously received filler in the same region of infection, or had an underlying autoimmune condition. Other risk factors noted in Table 4 include immunodeficiency and smoking. The literature provides multiple sources that had shown reduced levels of healing in smokers after general surgery, including facelifts, and there are some cases reported of late-onset infections, specifically post-dermal filler treatment in patients who smoke.27

Kadocch et al19 found 25 patients who developed abscesses at the site of permanent filler Bio-Alcamid polyacrylamide gel (Polymekon; Milan, Italy) and almost 70 percent of these had underlying human immunodeficiency virus.19 This illustrates how immune status and the properties of the soft tissue filler influence the development of post-treatment complications, including acute and DON.

Alijotas-Reig at al20 also propose that permanent fillers carry more risk than non-permanent filler in regard to inflammatory nodules. They also suggested that these complications have a genetic predisposition to affect certain patients. Furthermore, skin flora and bacteria that reside in apocrine glands and sebaceous glands can also play a role in the development of abscesses secondary to soft tissue filler.19

Location of the abscess influences the management strategy. For example, Funt and Pavicic22 explain how abscesses related to fillers in the midface and periorbital regions could potentially cause intracerebral complications.

Conrad et al26 specifically state the counterintuitive effects steroid injections might have on abscesses, and they found hyaluronidase to be beneficial. With HA being a glycosaminoglycan disaccharide, it provides optimal growing conditions for bacteria, hence, they argued that it should be dissolved. Similarly, Dayan et al25 found that steroids, as well as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, might actually promote biofilm production and exacerbate the infection.

Alternatively, DeLorenzi21 advised not to use hyaluronidase in the acute phase, as the infection might spread due to increased permeability from the actions of the hyaluronidase; however, he does then go on to utilize it for treating a recurrent cheek abscess, which fully resolved after hyaluronidase was used.

There have been multiple documented cases of hyaluronidase use in the acute phase, including in this paper, without worsening of inflammation.22 DeBoulle et al13 advocated for the use of hyaluronidase and discouraged steroids for the management of abscesses after HA fillers. They also suggested using macrolide plus a tetracycline antibiotic as empirical treatment.13 In addition, Rohrich et al18 recommended at least two antibiotics, including a quinolone and macrolide. This group also advised for the use of hyaluronidase in HA fillers.

Conclusion

It is clear that each case is unique, but there is no current universal consensus on the risk assessment before treatment nor general management of abscesses secondary to soft tissue filler. In the literature reviewed, the advice and use of microscopy, culture and sensitivity, antibiotics, I&D, and hyaluronidase all varied between cases.

The assessment of risk is important before any medical intervention, and injection of soft tissue filler is no exception. The literature points to several factors to consider in order to reduce the risk of localized (acute or delayed) infection following filler injection. These include general risks of infection, such as systemic illnesses, like diabetes, immune compromise (both iatrogenic and innate), genetic factors, and social factors (e.g., smoking), as well as recent ill health or surgery. Risks specific to filler injection include technique; repeated injections at the same site as well as the site itself playing a part in the risk profile. The type of filler used, with non-permanent filler, such as HA, being less of a risk when compared with more permanent filler types in DON formation. These factors should be considered when making a treatment plan for patients.

The majority of the reports we reviewed suggested the use of co-amoxiclav along with a macrolide or quinolone for at least two weeks. Moreover, while microbiology, cultures, and sensitivities are not routinely performed for general cutaneous abscesses, it is recommended and performed the majority of the time for abscesses secondary to HA filler. While there is some controversy surrounding the use of hyaluronidase in an area of active infection, the majority of the literature supports its use in cases of an abscess, as the filler acts as a growth medium.

I&D is almost universally accepted as the gold standard and must be performed. Regular reviews, referral to specialists, and treatment of the mass as a DON all need to be considered in the management process.

Abscesses are a rare, but serious complication of HA dermal filler treatments. With the increase use of dermal fillers globally, we must expect a higher incidence rate of such complications. Therefore, thorough assessment of possible risk factors prior to HA filler treatment, detailed management guidelines, patient adherence, and referral pathways are needed to ensure appropriate patient safety and management. One such referral pathway could include having private microbiology labs affiliated with Aesthetic Clinics carrying out injectable treatments. This would allow for swift and clear continuity of care, which will optimize patient outcomes.

Following our dissection of the available literature, we present Figure 2; a proposed management flow diagram for an abscess secondary to HA filler.

References

- NHS site. Abscess Treatment. Updated 4 Nov 2019. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/abscess/treatment/. Accessed 22 Sept 2020.

- Vermandere M, Aertgeerts B, Agoritsas T, et al. Antibiotics after incision and drainage for uncomplicated skin abscesses: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2018;360:k243.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: Executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):285–292.

- Salava A. Skin abscess and folliculitis. Evidence-Based Med Guidelines. https://www.ebm-guidelines.com/go/ebm/ebm00273.html. Accessed 15 Apr 2020.

- Bons S, Bouma M, Draijer L, et al. NHG-standaard bacteriële huidinfecties (tweede herziening). May 2017. NHG website. https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/bacteriele-huidinfecties. Accessed 15 Apr 2020.

- Korownyk C, Allan GM. Evidence-based approach to abscess management. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(10):1680–1684.

- Schmitz G, Goodwin T, Singer A, et al. The treatment of cutaneous abscesses: Comparison of emergency medicine providers’ practice patterns. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14(1):23–28.

- Fahimi J, Singh A, Frazee B. The role of adjunctive antibiotics in the treatment of skin and soft tissue abscesses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CJEM. 2015;17(4):420–432.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–52.

- List M, Headlee D, Kondratuk K. Treatment of skin abscesses: A review of wound packing and post-procedural antibiotics. S D Med. 2016;69(3): 113–119.

- NHS site. Abscess Treatment. Updated 4 Nov 2019. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/abscess/treatment/. Accessed 22 Sept 2020.

- Vermandere M, Aertgeerts B, Agoritsas T et al. Antibiotics after incision and drainage for uncomplicated skin abscesses: A clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2018;360:k243.

- De Boulle K, Heydenrych I. Patient factors influencing dermal filler complications: Prevention, assessment, and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:205–214.

- Davies E, King M. Management of acute skin infections. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10(2):E5–E7.

- King M, Bassett S, Davies E, King S. Management of delayed onset nodules. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9(11):E1–E5.

- Urdiales-Gálvez F, Delgado N, Figueiredo V et al. Treatment of soft tissue filler complications: Expert consensus recommendations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42(2):498–510.

- Kim J, Ahn D, Jeong H, Suh I. Treatment algorithm of complications after filler injection: Based on wound healing process. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(S3):S176.

- Rohrich R, Monheit G, Nguyen A, Brown S, Fagien S. Soft tissue filler complications: The important role of biofilms. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:1250–1256.

- Kadocch JA, Kadocch DJ, Fortuin S, et al. Delayed-onset complications of facial soft tissue augmentation with permanent fillers in 85 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(10):1474–1485.

- Alijotas-Reig J, Fernández-Figueras M, Puig L. Late-onset inflammatory adverse reactions related to soft tissue filler injections. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45(1):97–108.

- DeLorenzi C. Complications of injectable fillers, Part 1. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(4):561–575.

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: An overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Plast Surg Nurs. 2015;35:13–32

- Rzany B, DeLorenzi C. Understanding, avoiding, and managing severe filler complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(S5):196S–203S.

- Rousso J, Pitman M. Enterococcus faecalis complicating dermal filler injection: A case of virulent facial abscesses. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(10):1638–1641.

- Dayan S, Arkins J, Brindise R. Soft tissue fillers and biofilms. Facial Plast Surg. 2011;27(1):23–28.

- Conrad K, Alipasha R, Thiru S, Kandasamy T. Abscess formation as a complication of injectable fillers. Modern Plastic Surgery. 2015;5(2):14–18.

- Knobloch K, Vogt P. Smoking and soft-tissue dermal fillers: A potentially detrimental combination? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(1):345.

- King M, Convery C, Davies E. This month’s guideline: The use of hyaluronidase in aesthetic practice (v2.4). J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(6):E61–E68.